WORK EXPERIENCE

- Marissa Lehner

- Mar 31, 2021

Why are Negative Peace and Positive Peace Important?

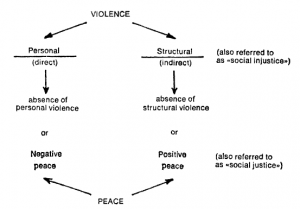

What does it mean to hope for world peace? It is an elusive concept that often seems closer to a vague state than a tangible goal. There are many different ways of talking about and defining peace, with each one trying to come closer to making peace an achievable goal. Johan Galtung, considered the father of peace studies, is responsible for one of the most common of these classifications. His work takes the idea of peace and breaks it down into two different categories: negative peace and positive peace.

Negative peace can be defined most simply as the absence of violence.1 Actions taken in order to achieve negative peace, then, are those that aim to prevent or stop explicit violence from occurring. These types of actions are extremely common, mostly because many of the actions that states and organizations take in pursuit of peace fall into this category. A classic example is peacekeeping. On an international scale, modern peacekeeping utilizes third parties, typically United Nations Peacekeepers, in order to prevent violence from breaking out.2 Essentially, peacekeeping enforces negative peace. Achieving negative peace is often the first goal when it comes to maintaining peaceful societies, as outright violence is an obvious indicator that a society is not peaceful.

However, the absence of violence does not necessarily mean that a society is peaceful. Another important measure of this would be positive peace, which looks at the underlying conditions of the society and works to take action towards creating a sustainable peace.3 Often, this takes the form of eliminating many of the conditions that have to do with perpetuating violence on a structural level.4 Unlike negative peace, which targets active outbreaks of violence, positive peace targets oppression and inequality. One of the major aspects of this is cooperation, which is often seen through peacebuilding efforts. Peacebuilding works towards replacing structures that reinforce war and violence with those that reinforce peace, often by targeting and eliminating issues like inequality.5 According to Galtung, this is how peace becomes sustainable – by providing structural alternatives to violence through cooperation. Another crucial part of this process is communication, especially what is known as nonviolent communication. Nonviolent communication focuses on speaking and listening in way that emphasizes meeting the needs of others and utilizing compassion.6 This process focuses on communicating observations, feelings, needs, and requests.7 If those on both sides of a conflict are able to believe that their needs are being heard and acknowledged, it allows them to focus on working towards a solution, as opposed to taking out their anger. In this way, nonviolent communication promotes positive peace. Establishing a dialogue between parties becomes one of the structures that replaces violence.

Negative and positive peace are not contradictory, but complimentary. In order for a truly peaceful and nonviolent society to be achieved, there must be both the absence of violence and continued cooperation towards a sustainable culture of peace.8 This is reflected even in the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, with Goal 16 setting out to not only reduce all forms of violence, but also strengthen institutions and policies to prevent further forms of violence.9 There is only so much progress that can be made towards cooperation and sustainable peace when there is still active violence. Similarly, a lack of violent conflict does not mean that a society is at peace. It takes both negative and positive peace to achieve a truly peaceful society.

1. Johan Galtung, “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research,” Journal of Peace Research 6, no. 3 (1969).

2. Johan Galtung, “Three Approaches to Peace: Peacekeeping, Peacemaking, and Peacebuilding” (Galtung-Institut for Peace Theory and Peace Practice, n.d.), https://www.galtung-institut.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/galtung_1976_three_approaches_to_peace.pdf.

3. Johan Galtung, “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research,” Journal of Peace Research 6, no. 3 (1969).

5. Johan Galtung, “Three Approaches to Peace: Peacekeeping, Peacemaking, and Peacebuilding” (Galtung-Institut for Peace Theory and Peace Practice, n.d.), https://www.galtung-institut.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/galtung_1976_three_approaches_to_peace.pdf.

6. Marshall Rosenberg, “Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life,” Center for Nonviolent Communication, n.d., https://www.cnvc.org/training/resource/book-chapter-1.

7. “The NVC Model,” Center for Nonviolent Communication, n.d., https://www.cnvc.org/learn-nvc/the-nvc-model.

8. “An Interview with Johan Galtung,” Peace Insight, n.d., https://www.peaceinsight.org/en/articles/interview-johan-galtung/?location=sudan&theme=peace-education

9. “Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions – United Nations Sustainable Development,” United Nations (United Nations, n.d.), https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/peace-justice/ .

Recent Posts

Gender Perspectives and the Disarmament Regime

LEE Methodology

Non-Profit Toolkit Blog Series: Part 12 - Empowering Action: A Call to Build a Brighter Future

The difference between positive and negative peace

According to the World Health Organization, peace is “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” In other words, peace is more than just the absence of conflict. Peace is a state of harmony and wellbeing.

There are two types of peace: positive peace and negative peace. Negative peace is the absence of violence or conflict. It’s when people are not fighting or actively harming one another. Positive peace, on the other hand, is more than just the absence of violence. It’s a state of harmony and wellbeing. Positive peace includes things like respect, justice, and equality. It’s about more than just avoiding conflict; it’s about creating a peaceful environment where everyone can thrive.

So, what’s the difference between positive and negative peace? Put simply, negative peace is the absence of violence while positive peace is the presence of harmony. One is about avoiding conflict while the other is about creating a peaceful environment where everyone can thrive.

Negative peace

Negative peace is the absence of violence or the absence of war. It is often thought of as the only type of peace, when there is no fighting or violence. The advantage of negative peace is that it can prevent violence and war. If people are not fighting, then they are not causing harm to each other. The disadvantage of negative peace is that it does not always lead to justice or fairness. In some cases, the absence of violence can be used to maintain an unjust status quo. For example, a dictator might keep control of a country by using violence to suppress any dissenters. Or, a group in power might use its economic power to keep others from having a voice. So, while negative peace can prevent violence, it does not always create a just and peaceful world.

Positive peace

Positive peace is more than just the absence of violence. It’s a state of well-being that includes social, economic, and political factors. When individuals are free from conflict and have the resources they need to thrive, they’re more likely to lead healthy, productive lives. And when societies are peaceful, they can attract investment, promote tourism, and create opportunities for trade and cooperation. In other words, positive peace benefits not only individuals but also entire communities. So why not strive for it? Everyone deserves to live in a safe, stable environment where they can reach their full potential. Working together to achieve positive peace is one way we can make the world a better place for everyone.

Society achieves positive peace by creating an environment where conflict is managed constructively and people feel safe and secure. This can be done through a variety of means, such as developing effective institutions, fostering social cohesion, and promoting respect for human rights. When people feel safe and have their basic needs met, they are more likely to trust others and work together to resolve differences. When conflict is managed effectively, it can provide an opportunity for growth and learning. And when people feel respected and valued, they are more likely to contribute to a peaceful society. By investing in peace-building efforts, we can create a more just and peaceful world for all.

A framework for positive peace in society can be built on the foundation of education. By teaching people about the benefits of peace and how to resolve conflict constructively, we can help create a generation of people who are more likely to choose peace over violence. Additionally, community-based programs that promote cross-cultural understanding and respect can help reduce tensions between different groups. Finally, laws and policies that protect the rights of all individuals and groups can create a society that is more just and equitable, making it less likely to erupt into violence. By working together to build a framework for positive peace, we can create a more peaceful world for everyone.

Related Posts

Peace , Social Change

The importance of cultivating inner peace for changemakers

What are UN Peacekeepers

Why The Hague is known as the ‘international city of peace and justice’

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- ISQ Data Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About International Studies Quarterly

- About the International Studies Association

- Editorial Team

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Exploring Peace: Looking Beyond War and Negative Peace

Paul F. Diehl is Associate Provost and Ashbel Smith Professor of Political Science at the University of Texas-Dallas. Previously, he was Henning Larsen Professor of Political Science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He served as President of the International Studies Association for the 2015-16 term. His areas of expertise include the causes of war, UN peacekeeping, and international law.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Paul F. Diehl, Exploring Peace: Looking Beyond War and Negative Peace, International Studies Quarterly , Volume 60, Issue 1, March 2016, Pages 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqw005

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Concern about war and large-scale violence has long dominated the study of international security. To the extent that peace receives any scholarly attention, it primarily does so under the rubric of “negative peace:” the absence of war. This article calls for a focus on peace in international studies that begins with a reconceptualization of the term. I examine the limitations of negative peace as a concept, discuss “positive peace,” and demonstrate empirically that Nobel Peace Prize winners have increasingly been those recognized for contributions to positive peace. Nevertheless, scholarly emphasis remains on war, violence, and negative peace—as demonstrated by references to articles appearing in a leading peace-studies journal and to papers presented at International Studies Association meetings. Peace is not the inverse or mirror image of war and therefore requires different theoretical orientations and explanatory variables. The article concludes with a series of guidelines on how to study peace.

International Studies Association members

Personal account.

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| January 2017 | 15 |

| February 2017 | 65 |

| March 2017 | 42 |

| April 2017 | 43 |

| May 2017 | 28 |

| June 2017 | 29 |

| July 2017 | 34 |

| August 2017 | 37 |

| September 2017 | 113 |

| October 2017 | 74 |

| November 2017 | 67 |

| December 2017 | 38 |

| January 2018 | 79 |

| February 2018 | 32 |

| March 2018 | 36 |

| April 2018 | 37 |

| May 2018 | 37 |

| June 2018 | 18 |

| July 2018 | 20 |

| August 2018 | 38 |

| September 2018 | 62 |

| October 2018 | 41 |

| November 2018 | 27 |

| December 2018 | 28 |

| January 2019 | 107 |

| February 2019 | 97 |

| March 2019 | 65 |

| April 2019 | 85 |

| May 2019 | 76 |

| June 2019 | 39 |

| July 2019 | 46 |

| August 2019 | 50 |

| September 2019 | 70 |

| October 2019 | 65 |

| November 2019 | 61 |

| December 2019 | 102 |

| January 2020 | 129 |

| February 2020 | 51 |

| March 2020 | 47 |

| April 2020 | 70 |

| May 2020 | 40 |

| June 2020 | 34 |

| July 2020 | 47 |

| August 2020 | 41 |

| September 2020 | 79 |

| October 2020 | 138 |

| November 2020 | 77 |

| December 2020 | 88 |

| January 2021 | 100 |

| February 2021 | 82 |

| March 2021 | 54 |

| April 2021 | 88 |

| May 2021 | 165 |

| June 2021 | 99 |

| July 2021 | 131 |

| August 2021 | 101 |

| September 2021 | 215 |

| October 2021 | 424 |

| November 2021 | 435 |

| December 2021 | 196 |

| January 2022 | 195 |

| February 2022 | 236 |

| March 2022 | 264 |

| April 2022 | 413 |

| May 2022 | 317 |

| June 2022 | 150 |

| July 2022 | 74 |

| August 2022 | 96 |

| September 2022 | 152 |

| October 2022 | 256 |

| November 2022 | 197 |

| December 2022 | 195 |

| January 2023 | 188 |

| February 2023 | 124 |

| March 2023 | 220 |

| April 2023 | 134 |

| May 2023 | 132 |

| June 2023 | 95 |

| July 2023 | 117 |

| August 2023 | 303 |

| September 2023 | 184 |

| October 2023 | 339 |

| November 2023 | 149 |

| December 2023 | 218 |

| January 2024 | 265 |

| February 2024 | 239 |

| March 2024 | 310 |

| April 2024 | 216 |

| May 2024 | 142 |

| June 2024 | 40 |

| July 2024 | 21 |

| August 2024 | 7 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-2478

- Print ISSN 0020-8833

- Copyright © 2024 International Studies Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Johan Galtung and the Quest to Define the Concept of Peace

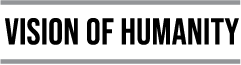

The quest to define peace as a concept and set of values is as old as recorded history.

The concept of peace was first introduced into academic literature by the Norwegian pioneer of peace research Johan Galtung, who distinguished between two types of peace: positive peace and negative peace.

Johan Galtung and the Quest to Define Peace

While the quest to define peace as a concept and set of values is as old as recorded history, the effort to provide a systemic definition of peace within a rational and humane paradigm, informed by best-practice methodologies for research and analysis is a more modern enterprise.

Nonetheless, it has become common to cultures and religions worldwide and recent developments have underscored the urgency of this quest for peace.

While deaths from violent crimes may continue to decline, the possibility of a power struggle between major world powers is at its most likely point since the Cold War — a febrile state that has only been exacerbated by the impacts of the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Additionally, despite diminishing lethality, terrorist activity has continued to spread globally and is especially harmful to the sustenance of peace in states deemed to be fragile.

Johan Galtung distinguished between positive and negative peace

Consequently, in pursuit of a holistic definition of peace, IEP research draws from the concept of ‘Positive peace’.

A term that was first introduced into academic literature by the Norwegian pioneer of peace research Johan Galtung, who distinguished between two types of peace:

Negative peace , which is defined by the absence of war and violence, and p ositive peace , which is defined by a more lasting peace, built on sustainable investments in economic development and institutions as well as the societal attitudes that foster peace.

In this context, it is essential to consider the long historical evolution of the concept of peace, which has been enriched by progressive definitions of its meaning and by ever-evolving methodologies for its implementation.

Johan Galtung was influenced by Gandhi

Johan Galtung was influenced in his philosophy of peace by the pacifism of Gandhi. The iconic Indian leader and political ethicist, famously concerned with understanding and implementing non-violent forms of civil resistance, coined the term satyagrha.

Satyagrha refers to a universal value of truth and peacefulness — where strength comes through enacting non-violent and peace-affirming practices.

Similarly, the economist Kenneth Boulding , a contemporary of Johan Galtung and early proponent of systems theory, identified the need to establish stable peace.

A durable and resilient peace, which minimises the risk of a relapse of the system into war. B oulding, like other pioneers of peace and conflict studies, sought to understand how social systems change over time and to analyse which institutions and structures within the system were conducive to stable peace and which worked against it.

Closing thoughts

In many ways, Galtungs’ theory of Positive Peace neatly encapsulates the philosophies of both Gandhi and Boulding. Stressing the importance of attitudes — like satyagrha — and institutions in actively improving the social, economic and political factors that promote peace.

A legacy which the IEP continues through its research into Positive Peace.

Are you interested in learning more about peace? Sign up for the free, online Positive Peace Academy here.

Up Next: “We Need to Find Peace Within: Lessons from Leo Tolstoy “

Vision of Humanity

Editorial staff.

Vision of Humanity is brought to you by the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), by staff in our global offices in Sydney, New York, The Hague, Harare and Mexico. Alongside maps and global indices, we present fresh perspectives on current affairs reflecting our editorial philosophy.

RELATED POSTS

Building Peace and Human Resilience During The Pandemic

It is a reminder that these Pillars are crucial, not only to preventing violence but allowing society to weather both internal and external shocks.

RELATED RESOURCES

October 2019

Positive peace report 2019.

Analysing the factors that sustain peace.

Global Peace Index 2020

Measuring peace in a complex world.

Never miss a report, event or news update.

Subscribe to the Vision Of Humanity mailing list

- Email address *

- Future Trends (Weekly)

- VOH Newsletter (Weekly)

- IEP & VOH Updates (Irregular)

- Consent * I understand this information will be used to contact me. *

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Kant's Rational Freedom: Positive and Negative Peace

2022, Peaceful Approaches for a More Peaceful World

World peace was a common theoretical consideration among philosophers during Europe’s Enlightenment period. The first robust essay on peace was written by Charles Irénée Castel de Saint- Pierre, which sparked an intellectual debate among prominent philosophers like Jean- Jacques Rousseau and Jeremy Bentham, who offered their own treatises on the concept of peace. Perhaps the most influential of all such writings comes from Immanuel Kant, who argues that world peace is no “high- flown or exaggerated notion” but rather a natural result of the rational progression of the human species. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, the mastermind behind the formation of the League of Nations in 1920 that provided the scaffolding to today’s United Nations, read Kant’s philosophy while he was a student at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). Some have argued that it is no coincidence that the per-son responsible for embarking upon the first serious political pursuit of world peace on a global scale was familiar with Kant. Indeed, William Galston claims that “Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points [for world peace] were a faithful transcription of both the letter and spirit of Kant’s Perpetual Peace.”3 Historical connections aside, the question remains as to whether Kant’s philosophy is a viable conception of peace in a contemporary context. Using the conceptual distinction of positive and negative peace provided by Johan Galtung, I argue that Kant’s philosophy does provide the scaffolding for a viable conception of peace. In particular, I provide particular examples as to what social rights must be included in a Kantian model of peace.

Related Papers

luigi caranti

Scholars working on democratic peace theory (DPT) often think of their work as nothing but a rejuvenation of Kant's insights, backed by empirical data only available to contemporary observers with a vantage view point of two centuries of historical events. Kant's theory of peace and DPT, however, are two very different models and marking the difference is the central aim of this paper. We aim to show that each of the three pillars on which Kant's theory rests (the three definitive articles) has been misinterpreted by DPT scholars. We also intend to show that Kant's model is superior to DPT from a normative standpoint, i.e. it offers better guidance for progressing towards a more peaceful world than the model based on the 'separate peace' dear to Michael Doyle and his followers. Given these two goals, the paper naturally falls into two main parts. The first part criticizes the way DPT scholars read Kant and marks the distance between the two models. The second part shows how the Kantian model, now clearly distinguished from DPT, articulates a path for the pacification of international relations that is considerably more attractive than the model suggested by DPT.

Rishesh C Singh

As globalism continues to impact modern economies, and as the strength of global governing bodies (e.g. - the U.N.) expands alongside it, a system of world government seems inevitable. Many are quick to jump on the throat of any such notion, but Kant actually shows us in these works why he believes that the creation of such a governing body is a mere eventuality....and why it's a good thing.

Dokuz Eylül University Journal of Humanities

Lucas Thorpe

The ideal of the United Nations was first put forward by Immanuel Kant in his 1795 essay Perpetual Peace. Kant, in the tradition of Locke and Rousseau is a liberal who believes that relations between individuals can either be based upon law and consent or upon force and violence. One way that such the ideal of world peace could be achieved would be through the creation of a single world state, of which every human being was a citizen. Such an ideal was advocated by a number of eighteenth century liberals. Kant, however, rejects this ideal and instead argues that the universal rule of law can be achieved through the establishment a federation of independent states. I examine the relevance of Kant's arguments today, focusing on two questions: Firstly, as advocates of the rule of law, why advocate a federation of independent nations rather than a single world state. Secondly, is this ideal realizable? Is Kant right to think that republics are natural and are likely to live peacefully with one another? Kant's arguments on this issue have been taken up again in recent decades by defenders of the theory of the "democratic peace", the theory that democracies are more likely to live at peace with one another.

This book focuses on Kant’s analysis of three issues crucial for contemporary politics. Starting from a new reading of Kant’s account of our innate right to freedom, it highlights how a Kantian foundation of human rights, properly understood and modified where necessary, appears more promising than the foundational arguments currently offered by philosophers. It then compares Kant’s model for peace with the apparently similar model of democratic peace to show that the two are profoundly different in content and in quality. The book concludes in analysis of Kant’s controversial view of history to rescue it from the idea that his belief in progress is at best over-optimistic and at worst dogmatic.

Review of International Studies

Georg Cavallar

Brandon Pakker

Since the dawn of its existence the concept of peace has, of course, given rise to a plethora of meanings. The concept has been and still is consistently employed in both inter- as well as intrapersonal matters of discourse. In accordance with the former, one can rightly ask what the concept of peace is to mean within the domain of (international) politics and how it can be obtained in practice. What then are we to make of the idea of a ‘perpetual peace’? If peace is negatively and stringently defined as a mere absence of war, it is not surprising to find that a perpetual peace has not been established, given the history and nature of humankind. Rather, the concept of a perpetual peace seems an ideal at best, the materialization of which difficult if not outright impossible to obtain. Perhaps it was with a similar hint of irony with which a Dutch innkeeper once decided to name his inn ‘The Perpetual Peace’, accompanied with an image of a graveyard on his signboard. It was this scenario that too, perhaps, prompted Kant to awake from yet another ‘slumber’, culminating in his often overlooked and underestimated essay ‘Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch’. In the first section of this foundational essay, Kant argues for six Preliminary Articles that he conceived as a priori conditions that need to be satisfied in order to approximate peace proper, viz., perpetual peace. In the second section, Kant outlines three Definite Articles in which he provides a foundational framework on which a perpetual peace is thought able to rest. The major aim of this thesis is to provide an analysis of Kant’s Preliminary Articles as formulated in his Perpetual Peace. In doing so, I will focus primarily on the relevant sections of his essay and provide secondary commentary where I deem it valuable. Finally, I will situate each of these conditions in a contemporary context and investigate to what extent the Dutch political system as being embedded in international law conforms to the necessary conditions here specified. As will become clear, several key documents implemented within the international legal system do appear to have adopted elements of the Kantian framework discussed. In order to make the translation from the 18th century to the modern world feasible, I will make use of a broad interpretation of the conditions in question without thereby losing their conceptual core.

In Valerio Rohden, Ricardo R. Terra and Guido A. de Almeida (eds.), Recht und Frieden in der Philosophie Kants, vol. 4 of Akten des X. Internationalen Kant-Kongresses (Berlin: de Gruyter)

Stephen R Palmquist

This essay interprets the much-neglected Second Part of The Conflict of the Faculties, entitled “An old question raised again: Is the human race constantly progressing?”, by showing the close relationship between the themes it deals with and those Kant addresses in the Supplements and Appendices of Perpetual Peace. In both works, Kant portrays the philosopher as having the duty to promote a “secret article”, without which his vision of a lasting international peace through the agency of a federation of states is bound to fail. Both works identify this article as involving the necessity of publicity as a transcendental condition for peace, and call for philosophers to engage politicians and lawyers in a creative attitude towards lawmaking. Kant’s visionary program has failed to reach its goal up to now, not because it is too idealistic, but because philosophers have failed to take up the challenge.

Theoria, Beograd

Nenad Milicic

Bekim Sejdiu

This paper exploits academic parameters of the democratic peace theory to analyze the UN’s principal mission of preserving the world peace. It inquires into the intellectual horizons of the democratic peace theory – which originated from the Kant’s “perpetual peace” – with the aim of prescribing an ideological recipe for establishing solid foundation for peace among states. The paper argues that by promoting democracy and supporting democratization, the UN primarily works to achieve its fundamental mission of preventing the scourge of war. It explores practical activities that the UN undertakes to support democracy, as well as the political and normative aspects of such an enterprise, is beyond the reach of this analysis. Rather, the focus of the analysis is on the democratic peace theory. The confirmation of the scientific credibility of this theory is taken as a sufficient argument to claim that by supporting democracy the UN would advance one of its major purposes, namely the goa...

William Rasch

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Journal of Human Rights

European Journal of Philosophy

Pauline Kleingeld

Journal of academic research for humanities

JARH Print & Online ResearchJournal for Humanities

Chiara Bottici

International Res Jour Managt Socio Human

Werner Ulrich's Home Page, "Downloads" section.

Werner Ulrich

Mbang Y Eta

Peace Studies Journal

Chad Kautzer

Muhammad Fahad

European Journal of International Relations

Clockwork Mel

Randolph Siverson

Benjamin E Goldsmith

Terry Nardin

Vicent Martinez Guzman

Edinburgh University Press eBooks

Howard Williams

Cuadernos Constitucionales De La Catedra Fadrique Furio Ceriol

fatuma ahmed

Comparative Political Theory

Daniel Hutton Ferris

Inés Valdez

Elisabeth Ellis

Con-Textos Kantianos. International Journal of Philosophy

Alice Pinheiro Walla

The Routledge Handbook of Ethics and International Relations, eds. B. Steele and E. Heinze, New York: Routledge Press

Matthew Lindauer

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

AND INTERAMERICAN PEACE PROCESS WIKI

Negative and Positive Peace Framework

A dichotomous negative and positive peace framework is perhaps the most widely used today. Negative peace refers to the absence of direct violence. Positive peace refers to the absence of indirect and structural violence , and is the concept that most peace and conflict researchers adopt. The basic distinction between positive and negative peace was popularized by prominent peace theorist Johan Galtung.

While the dichotomy is often credited to Galtung, he was not the first to describe it. Martin Luther King in the Letter from a Birmingham Jail in 1953 , in which he wrote about "negative peace which is the absence of tension" and "positive peace which is the presence of justice."

These terms were likely used first by Jane Addams in her1907 book Newer Ideals of Peace . Berenice A. Carroll and Clinton F. Fink note: "Addams expressed this idea in 1899...in saying that the concept of peace had become 'no longer merely absence of war.' But in Newer Ideals of Peace , Addams used the term "negative peace" also in a different and more complex sense, to characterize certain older ideals of peace that she held to be negative or inadequate. In this sense her use of the term brought with it the implication that peace should be understood to encompass more adequate and positive goals and principles."

- Campus Advisories

- EO/Nondiscrimination Policy

- Website Privacy Notice

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Report a barrier to accessibility.

This site uses cookies to offer you a better browsing experience. Visit GW’s Website Privacy Notice to learn more about how GW uses cookies.

- Analytical Tools

- Peace Index

- Publications

Irenees.net is a documentary website whose purpose is to promote an exchange of knowledge and know-how at the service of the construction of an Art of peace. This website is coordinated by Modus Operandi

- Festival Images migrantes "Du migrant au sujet politique"

- Universitat Internacional de la Pau

- Écoutes de créations radio et migrations

- Articulation entre le droit à la ville et la transition écologique à Grenoble

- Le droit à la ville, résonances et appropriations contemporaines

- Savoirs au service de l’action #2

Claske DIJKEMA , Saint Martin d’Hères, May 2007

Negative versus Positive Peace

Johan Galtung, the father of peace studies often refers to the distinction between ‘negative peace’ and ‘positive peace’ (e.g. Galtung 1996). Negative peace refers to the absence of violence. When, for example, a ceasefire is enacted, a negative peace will ensue. It is negative because something undesirable stopped happening (e.g. the violence stopped, the oppression ended). Positive peace is filled with positive content such as restoration of relationships, the creation of social systems that serve the needs of the whole population and the constructive resolution of conflict.

Peace does not mean the total absence of any conflict. It means the absence of violence in all forms and the unfolding of conflict in a constructive way.

Peace therefore exists where people are interacting non-violently and are managing their conflict positively – with respectful attention to the legitimate needs and interest of all concerned.

The authors of this dossier consider peace as well-managed social conflict. This definition was decided on during Irenees’ Peace workshop held in South Africa in May 2007.

- Becoming an author

- Legal Notices

- Irenees is a member of Coredem

- Modus operandi

Peace in Peace Studies: Beyond the ‘Negative/Positive’ Divide

- First Online: 12 October 2019

Cite this chapter

- Gijsbert M. van Iterson Scholten 3

Part of the book series: Rethinking Peace and Conflict Studies ((RCS))

618 Accesses

This chapter provides an overview of the academic debate on peace and peacebuilding. It starts with a discussion of classical concepts of peace, such as the well-known dichotomy between positive and negative peace, stable peace, peace as process and the democratic peace thesis. Along the way, seven dimensions are introduced along which these concepts differ from one another.

The second half of the chapter is devoted to the peacebuilding literature, specifically the liberal peace debates. It argues that these debates are not just about the best way to achieve lasting peace in (post-) conflict societies, but more fundamentally about different visions of what constitutes such a peace. Besides the liberal peace itself, four other visions can be distilled from the literature: hybrid peace, agonistic peace, welfare and everyday peace. Using the dimensions identified earlier in the chapter, these visions are compared to one another in order to disentangle what is at stake for the different sides.

We cannot be adequate problem solvers or social scientists if we cannot articulate a definition of or the conditions for peace. (Patrick M. Regan, Presidential address to the Peace Science Society (Regan 2014 : 348))

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

These were the two names that came up most frequently in response to the background question whether an interviewee was familiar with the academic literature on peace and could name any authors that had influenced his or her thinking. See the interview guide in Appendix E.

For a similar approach, but focused on International Relations (IR) theory, see (Richmond 2008a ).

This discussion does not cover even more classical visions of peace, such as those espoused by, e.g., Saint Augustine (Augustine 2010 : 212–220), Thomas Hobbes (Hobbes 2003 [1651]: 101–102) or Immanuel Kant (Kant 1976 [1796]). Although present-day peace researchers may cite those visions in support of their own, the primary purpose of this chapter is to establish a conceptual framework for present-day visions of peace, rather than giving a full historical overview of thinking about peace. For that, see, e.g. (Adolf 2009 ; Dietrich 2012 ; Hassner 1994 ).

It should be noted that this reading depends on a constructivist account of International Relations, as Rasmussen himself acknowledges (Rasmussen 2003 : 4).

Although, to be fair, there are also quite some political scientists who are interested in the economic underpinnings of peace (e.g. Gartzke 2007 ; Hegre et al. 2010 ).

See especially Chap. 3 , Sect. 3.2, Chap. 7 , Sect. 7.3.3 and Chap. 9 , Sect. 9.3.2 in the conclusion.

In a recent appraisal of the ‘hybrid turn’ in peacebuilding literature, Mac Ginty and Richmond even speak of hybridity as an ‘emergent social construct’ (Mac Ginty and Richmond 2016 : 221).

Clausewitz’s original maxim being that war is the continuation of policy—or (depending on the translation) of politics—with other means (Von Clausewitz 1984 [1832]: 87).

For a brief overview of the classical arguments, in an interstate context, but equally valid for intrastate conflicts, see, e.g. (Gartzke 2007 : 169–170).

In a seemingly largely forgotten essay, German peace scientist Ivan Illich called this ‘vernacular peace’ or Vride , after the medieval German word for this kind of peace. He contrasted the notion with the Roman word Pax that denoted the peace between rulers (Illich 1992 ).

According to Millar, the same is true for authors who want to prescribe a hybrid peace.

Interestingly, care and empathy also feature heavily in feminist approaches to IR. Feminist authors such as Carol Gilligan and Sara Ruddick contrast a male perspective of domination with a female perspective of care for others, arguing that the latter is inherently more peaceful than the former (Gilligan 2009 ; Ruddick 1995 ). Likewise, Christine Sylvester proposes ‘empathetic cooperation’ as a feminist method for IR (Sylvester 1994 ), raising empathy to a concern at the international level as well.

A point that will be developed in Chap. 8 on the Mindanaoan visions of peace.

Or, using Giddens’s terminology, in structures or in agents (Giddens 1979 ).

Adolf, A. (2009). Peace. A world history . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Google Scholar

Advisory Group of Experts (2015). The challenge of sustaining peace . Report of the Advisory Group of Experts for the 2015 Review of the United Nations peacebuilding architecture. New York: United Nations.

Aggestam, K., F. Cristiano, et al. (2015). “Towards agonistic peacebuilding? Exploring the antagonism–agonism nexus in the Middle East peace process.” Third World Quarterly 36(9): 1736–1753.

Article Google Scholar

Anderson, R. (2004). “A definition of peace.” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 10(2): 101.

Augustine, S. (2010). The city of god, books XVII–XXII (The Fathers of the church, volume 24) . CUA Press.

Austin, A., M. Fischer, et al. (2013). Transforming ethnopolitical conflict: The Berghof handbook . Springer Science & Business Media.

Autesserre, S. (2010). The trouble with the Congo: Local violence and the failure of international peacebuilding . Cambridge University Press.

Autesserre, S. (2014). Peaceland: Conflict resolution and the everyday politics of international intervention . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Babo-Soares, D. (2004). “Nahe Biti: The philosophy and process of grassroots reconciliation (and justice) in East Timor.” The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 5(1): 15–33.

Banks, M. (1987). “Four conceptions of peace.” In Conflict management and problem solving: Interpersonal to international applications . D. J. D. Sandole and I. Sandole-Staroste (Eds.). London: Pinter: 259–274.

Basabe, N. and J. Valencia (2007). “Culture of peace: Sociostructural dimensions, cultural values, and emotional climate.” Journal of Social Issues 63(2): 405–419.

Begby, E. and J. P. Burgess (2009). “Human security and liberal peace.” Public Reason 1(1): 91–104.

Bell, C. (2008). On the law of peace: Peace agreements and the Lex Pacificatoria . Oxford University Press.

Belloni, R. (2012). “Hybrid peace governance: Its emergence and significance.” Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations 18(1): 21–38.

Berents, H. and S. McEvoy-Levy (2015). “Theorising youth and everyday peace (building).” Peacebuilding 3(2): 115–125.

Björkdahl, A., K. Höglund, et al. (2016). Peacebuilding and friction: Global and local encounters in post conflict-societies . London and New York: Routledge.

Boege, V. (2011). “Potential and limits of traditional approaches in peacebuilding.” In Berghof handbook II: Advancing conflict transformation . B. Austin, M. Fischer, and H. J. Giessmann (Eds.). Berlin: Barbara Budrich Publishers: 431–457.

Boege, V. (2012). “Hybrid forms of peace and order on a South Sea Island: Experiences from Bougainville (Papua New Guinea).” In Hybrid forms of peace: From everyday agency to post-liberalism . O. Richmond and A. Mitchell (Eds.). Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan: 88–106.

Chapter Google Scholar

Boulding, K. E. (1977). “Twelve friendly quarrels with Johan Galtung.” Journal of Peace Research 14(1): 75–86.

Boulding, K. E. (1978). Stable peace . Austin: University of Texas Press.

Boutros-Ghali, B. (1992). An agenda for peace: Preventive diplomacy, peacemaking and peace-keeping . Report of the Secretary-General Pursuant to the statement adopted by the Summit Meeting of the Security Council on 31 January 1992. New York: UN.

Brigg, M. and P. O. Walker (2016). “Indigeneity and peace.” In The Palgrave handbook of disciplinary and regional approaches to peace . O. P. Richmond and S. Pogodda (Eds.). Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan: 259–271.

Brusset, E., C. De Coning, et al. (2016). Complexity thinking for peacebuilding practice and evaluation . Springer.

Burton, J. W. (1990). Conflict: Resolution and prevention . New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Caedel, M. (1987). Thinking about peace and war . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Call, C. T. (2008). “Knowing peace when you see it: Setting standards for peacebuilding success.” Civil Wars 10(2): 173–194.

Call, C. T. (2012). Why peace fails: The causes and prevention of civil war recurrence . Georgetown University Press.

Call, C. T. and E. M. Cousens (2008). “Ending wars and building peace: International responses to war-torn societies.” International Studies Perspectives 9(1): 1–21.

Carothers, T. (2007). “The “sequencing” fallacy.” Journal of Democracy 18(1): 12–27.

Chandler, D. (2004). “The responsibility to protect? Imposing the ‘liberal peace’.” International Peacekeeping 11(1): 59–81.

Chandler, D. (2006). Empire in denial: The politics of state-building . London: Pluto.

Chandler, D. (2010). “The uncritical critique of ‘liberal peace’.” Review of International Studies 36(S1): 137–155.

Chandler, D. (2017). Peacebuilding: The twenty years’ crisis, 1997–2017 . Springer.

Charbonneau, B. and G. Parent, Eds. (2013). Peacebuilding, memory and reconciliation: Bridging top-down and bottom-up approaches . London and New York: Routledge.

Chigas, D. (2014). “The role and effectiveness of non-governmental third parties in peacebuilding.” In Moving toward a just peace . Springer: 273–315.

Chopra, J. and T. Hohe (2004). “Participatory intervention.” Global Governance 10(3): 289–305.

Christie, D. J. (2006). “What is peace psychology the psychology of?” Journal of Social Issues 62(1): 1–17.

Cisnero, M. R. L. (2008). “Rediscovering olden pathways and vanishing trails to justice and peace: Indigenous modes of dispute resolution and indigenous justice systems.” In A sourcebook on alternatives to formal dispute resolution mechanisms. A publication of the Justice Reform Initiatives Support Project . C. Ubarra (Ed.). N.P.: National Judicial Institute of Canada.

Coleman, P. T. and M. Deutsch, Eds. (2012). Psychological components of sustainable peace . Peace Psychology Book Series. New York: Springer.

Collier, P. and A. Hoeffler (2004). “Greed and grievance in civil war.” Oxford Economic Papers 56(4): 563–595.

Connolly, W. E. (2002). Identity, difference: Democratic negotiations of political paradox . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Cooper, N., M. Turner, et al. (2011). “The end of history and the last liberal peacebuilder: A reply to Roland Paris.” Review of International Studies 1(1): 1–13.

Dafoe, A. (2011). “Statistical critiques of the democratic peace: Caveat emptor.” American Journal of Political Science 55(2): 247–262.

Daxecker, U. E. (2007). “Perilous polities? An assessment of the democratization-conflict linkage.” European Journal of International Relations 13(4): 527–553.

De Coning, C. (2018a). “Adaptive peacebuilding.” International Affairs 94(2): 301–317.

Dietrich, W. (2012). Interpretations of peace in history and culture . New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dietrich, W. and W. Sützl (1997). A call for many peaces . Peace Center Burg Schlaining.

Donais, T. (2009). “Empowerment or imposition? Dilemmas of local ownership in post-conflict peacebuilding processes.” Peace & Change 34(1): 3–26.

Doyle, M. W. (2005). “Three pillars of the liberal peace.” American Political Science Review 99(3): 463–466.

Doyle, M. W. and N. Sambanis (2000). “International peacebuilding: A theoretical and quantitative analysis.” American Political Science Review 94(4): 779–801.

Doyle, M. W. and N. Sambanis (2006). Making war and building peace: United Nations peace operations . Princeton University Press.

Duffield, M. R. (2001). Global governance and the new wars: The merging of development and security . London: Zed Books.

Fabbro, D. (1978). “Peaceful societies: An introduction.” Journal of Peace Research 15(1): 67–83.

Firchow, P. (2018). Reclaiming everyday peace: Local voices in measurement and evaluation after war . Cambridge University Press.

Fischer, R. and K. Hanke (2009). “Are societal values linked to global peace and conflict?” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 15(3): 227.

Fortna, V. P. (2004). “Does peacekeeping keep peace? International intervention and the duration of peace after civil war.” International Studies Quarterly 48(2): 269–292.

Fukuyama, F. (2006). The end of history and the last man . New York: Free Press.

Galtung, J. (1964). “An editorial.” Journal of Peace Research 1(1): 1–4.

Galtung, J. (1967). “On the future of the international system.” Journal of Peace Research 4(4): 305–333.

Galtung, J. (1969). “Violence, peace, and peace research.” Journal of Peace Research 6(3): 167–191.

Galtung, J. (2000). Conflict transformation by peaceful means: The transcend method . UN.

Galtung, J. (2007). “Introduction: Peace by peaceful conflict transformation—The transcend approach.” In Handbook of peace and conflict studies . C. Webel and J. Galtung (Eds.). London and New York: Routledge: 14–32.

Galtung, J. (2010). “Peace studies and conflict resolution: The need for transdisciplinarity.” Transcultural Psychiatry 47(1): 20–32.

Gartzke, E. (2007). “The capitalist peace.” American Journal of Political Science 51(1): 166–191.

Giddens, A. (1979). Central problems in social theory: Action, structure, and contradiction in social analysis . University of California Press.

Gilligan, C. (2009). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gleditsch, N. P., J. Nordkvelle, et al. (2014). “Peace research—Just the study of war?” Journal of Peace Research 51(2): 145–158.

Hassner, P. (1994). “Beyond the three traditions: The philosophy of war and peace in historical perspective.” International Affairs 70(4): 737–756.

Heathershaw, J. (2008). “Unpacking the liberal peace: The dividing and merging of peacebuilding discourses.” Millennium-Journal of International Studies 36(3): 597–621.

Heathershaw, J. (2009). Post-conflict Tajikistan: The politics of peacebuilding and the emergence of legitimate order . London and New York: Routledge.

Heathershaw, J. (2013). “Towards better theories of peacebuilding: Beyond the liberal peace debate.” Peacebuilding 1(2): 275–282.

Hegre, H. (2014). “Democracy and armed conflict.” Journal of Peace Research 51(2): 159–172.

Hegre, H., T. Ellingsen, et al. (2001). Toward a democratic civil peace? Democracy, political change, and civil war, 1816–1992 . American Political Science Association, Cambridge University Press.

Hegre, H., J. R. Oneal, et al. (2010). “Trade does promote peace: New simultaneous estimates of the reciprocal effects of trade and conflict.” Journal of Peace Research 47(6): 763–774.

Hilhorst, D. and M. Van Leeuwen (2005). “Grounding local peace organisations: A case study of Southern Sudan.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 43(4): 537–563.

Hobbes, T. (2003 [1651]). Leviathan: or The matter, forme, & power of a common-wealth ecclesiasticall and civill . Bristol: Thoemmes Continuum.

Illich, I. (1992). “The de-linking of peace and development. Opening address on the occasion of the first meeting of the Asian Peace Research Association, Yokohama, 1 December 1980.” In In the mirror of the past: Lectures and addresses, 1978–1990 . I. Illich and V. Borremans (Eds.). London: Marion Boyars Publishers.

Institute for Economics and Peace (2013). Pillars of peace : Understanding the key attitudes and institutions that underpin peaceful societies . IEP Reports. Sydney: Institute for Economics and Peace, 22.

Jarstad, A. K. and R. Belloni (2012). “Introducing hybrid peace governance: Impact and prospects of liberal peacebuilding.” Global Governance 18(1): 1–6.

Jenkins, R. (2013). Peacebuilding: From concept to commission . London and New York: Routledge.

Johnson, K. and M. L. Hutchison (2012). “Hybridity, political order and legitimacy: Examples from Nigeria.” Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 7(2): 37–52.

Kaldor, M. (2006). New and old wars . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Kant, I. (1976 [1796]). Zum ewigen Frieden. Ein philosophischer Entwurf . Stuttgart: Reclam.

Kelsen, H. (1944). Peace through law . Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Klein, N. (2007). The shock doctrine: The rise of disaster capitalism . Palgrave Macmillan.

Krijtenburg, F. (2007). Cultural ideologies of peace and conflict: A socio-cognitive study of Giryama discourse (Kenya) . Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam.

Krijtenburg, F. and E. de Volder (2015). “How universal is UN ‘peace’?: A comparative linguistic analysis of the United Nations and Giryama (Kenya) concepts of ‘peace’.” International Journal of Language and Culture 2(2): 194–218.

Kühn, F. P. (2012). “The peace prefix: Ambiguities of the word ‘peace’.” International Peacekeeping 19(4): 396–409.

Kustermans, J. (2012). Democratic peace as practice . PhD thesis, Faculteit Politieke en Sociale Wetenschappen, Departement Politieke Wetenschappen, Universiteit Antwerpen, Antwerpen.

Lederach, J. P. (1995). Preparing for peace: Conflict transformation across cultures . Syracuse University Press.

Lederach, J. P. (1997). Building peace: Sustainable reconciliation in divided societies . Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace.

Lederach, J. P. (2015). Little book of conflict transformation: Clear articulation of the guiding principles by a pioneer in the field . Simon and Schuster.

Lee, Y.-C., Y.-C. Lin, et al. (2013). “The construct and measurement of peace of mind.” Journal of Happiness Studies 14(2): 571–590.

Lefebvre, H. (1991 [1947]). Critique of everyday life. Volume 1: Introduction . London and New York: Verso Books.

Leonardsson, H. and G. Rudd (2015). “The ‘local turn’ in peacebuilding: A literature review of effective and emancipatory local peacebuilding.” Third World Quarterly 36(5): 825–839.

Liden, K. (2007). ‘What is the ethics of peacebuilding?’ Lecture prepared for the kick-off meeting of the Liberal Peace and the Ethics of Peacebuilding project. Peace Research Institute Oslo, January 18, 2007.

Lidén, K. (2009). “Building peace between global and local politics: The cosmopolitical ethics of liberal peacebuilding.” International Peacekeeping 16(5): 616–634.

Mac Ginty, R. (2006). No war, no peace: The rejuvenation of stalled peace processes and peace accords . Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mac Ginty, R. (2008). “Indigenous peace-making versus the liberal peace.” Cooperation and Conflict 43(2): 139–163.

Mac Ginty, R. (2010). “Hybrid peace: The interaction between top-down and bottom-up peace.” Security Dialogue 41(4): 391–412.

Mac Ginty, R. (2011). International peacebuilding and local resistance: Hybrid forms of peace . New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mac Ginty, R. (2012). “Routine peace: Technocracy and peacebuilding.” Cooperation and Conflict 47(3): 287–308.

Mac Ginty, R. (2013). “Indicators+: A proposal for everyday peace indicators.” Evaluation and Program Planning 36: 56–63.

Mac Ginty, R. (2014). “Everyday peace: Bottom-up and local agency in conflict-affected societies.” Security Dialogue 45(6): 548–564.

Mac Ginty, R. and G. Sanghera, Eds. (2012b). Special issue: Hybridity in peacebuilding and development. Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 7(2): 3–8.

Mac Ginty, R. and P. Firchow (2016). “Top-down and bottom-up narratives of peace and conflict.” Politics 36(3): 308–323.

Mac Ginty, R. and O. P. Richmond (2013). “The local turn in peace building: A critical agenda for peace.” Third World Quarterly 34(5): 763–783.

Mac Ginty, R. and O. Richmond (2016). “The fallacy of constructing hybrid political orders: A reappraisal of the hybrid turn in peacebuilding.” International Peacekeeping 23(2): 219–239.

Macmillan, J. (2003). “Beyond the separate democratic peace.” Journal of Peace Research 40(2): 233–243.

Mansfield, E. D. and J. Snyder (1995). “Democratization and the danger of war.” International Security 20(1): 5–38.

Mansfield, E. D. and J. Snyder (2007). Electing to fight: Why emerging democracies go to war . MIT Press.

McKeown Jones, S. and D. J. Christie (2016). “Social psychology and peace.” In The Palgrave handbook of disciplinary and regional approaches to peace . O. P. Richmond, S. Pogodda, and J. Ramovic (Eds.). Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Millar, G. (2014). “Disaggregating hybridity: Why hybrid institutions do not produce predictable experiences of peace.” Journal of Peace Research 51(4): 501–514.

Millar, G. (2016). “Local experiences of liberal peace.” Journal of Peace Research 53(4): 569–581.

Mouffe, C. (1993). The return of the political . London and New York: Verso.

Mouffe, C. (1999). “Deliberative democracy or agonistic pluralism?” Social Research 66(3): 745–758.

Münkler, H. (2005). The new wars . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Nadarajah, S. and D. Rampton (2015). “The limits of hybridity and the crisis of liberal peace.” Review of International Studies 41(1): 49–72.

Nagle, J. (2014). “From the politics of antagonistic recognition to agonistic peace building: An exploration of symbols and rituals in divided societies.” Peace & Change 39(4): 468–494.

Newman, E. (2009). “‘Liberal’ peacebuilding debates.” In New perspectives on liberal peacebuilding . E. Newman, R. Paris, and O. Richmond (Eds.). Tokyo: United Nations University Press: 26–53.

Nixon, H. and R. Ponzio (2007). “Building democracy in Afghanistan: The statebuilding agenda and international engagement.” International Peacekeeping 14(1): 26–40.

Noma, E., D. Aker, et al. (2012). “Heeding women’s voices: Breaking cycles of conflict and deepening the concept of peacebuilding.” Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 7(1): 7–32.

Oneal, J. R., F. H. Oneal, et al. (1996). “The liberal peace: Interdependence, democracy, and international conflict, 1950–85.” Journal of Peace Research 33(1): 11–28.

Owen, J. M. (1994). “How liberalism produces democratic peace.” International Security 19(2): 87–125.

Paarlberg-Kvam, K. (2018). “What’s to come is more complicated: Feminist visions of peace in Colombia.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 21(2): 1–30.

Paffenholz, T., Ed. (2010). Civil society & peacebuilding: A critical assessment . Boulder, CO and London: Lynne Rienner.

Paffenholz, T. (2014). “International peacebuilding goes local: Analysing Lederach’s conflict transformation theory and its ambivalent encounter with 20 years of practice.” Peacebuilding 2(1): 11–27.

Paffenholz, T. (2015). “Unpacking the local turn in peacebuilding: A critical assessment towards an agenda for future research.” Third World Quarterly 36(5): 857–874.

Paris, R. (2004). At war’s end: Building peace after civil conflict . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Paris, R. (2010). “Saving liberal peacebuilding.” Review of International Studies 36: 337–365.

Park, J. (2013). “Forward to the future? The democratic peace after the Cold War.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 30(2): 178–194.

Polat, N. (2010). “Peace as war.” Alternatives 35(4): 317–345.

Pugh, M. (2005). “The political economy of peacebuilding: A critical theory perspective.” International Journal of Peace Studies 10: 23–42.

Pugh, M. (2010). “Welfare in war-torn societies: Nemesis of the liberal peace?” In Palgrave advances in peacebuilding: Critical developments and approaches . O. Richmond (Ed.). London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan: 262–273.

Pugh, M., N. Cooper, et al., Eds. (2008). Whose peace? Critical perspectives on the political economy of peacebuilding . New Security Challenges. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Puljek-Shank, R. (2017). “Dead letters on a page? Civic agency and inclusive governance in neopatrimonialism.” Democratization 24(4): 670–688.

Ramsbotham, O. (2010). Transforming violent conflict: Radical disagreement, dialogue and survival . London and New York: Routledge.

Randazzo, E. (2016). “The paradoxes of the ‘everyday’: Scrutinising the local turn in peace building.” Third World Quarterly 37(8): 1351–1370.

Rapoport, A. (1992). Peace: An idea whose time has come . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Rasmussen, M. V. (2003). The west, civil society and the construction of peace . Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rausch, C. (2015). Speaking their peace. Personal stories from the frontlines of war and peace . Berkeley: Roaring Forties Press.

Regan, P. M. (2014). “Bringing peace back in: Presidential address to the Peace Science Society, 2013.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 31(4): 345–356.

Reiter, D., A. C. Stam, et al. (2016). “A revised look at interstate wars, 1816–2007.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 60(5): 956–976.

Richmond, O. P. (2005). The transformation of peace . Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Richmond, O. P. (2008a). Peace in international relations . London and New York: Routledge.

Richmond, O. P. (2008b). “Welfare and the civil peace: Poverty with rights?” In Whose peace? Critical perspectives on the political economy of peacebuilding . M. Pugh, N. Cooper, and M. Turner (Eds.). Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan: 287–301.

Richmond, O. P. (2009a). “A post-liberal peace: Eirenism and the everyday.” Review of International Studies 35: 557–580.

Richmond, O. P. (2011). A post-liberal peace . London and New York: Routledge.

Richmond, O. P. (2013). “Peace formation and local infrastructures for peace.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 38(4): 271–287.

Richmond, O. P. and J. Franks (2009). Liberal peace transitions: Between statebuilding and peacebuilding . Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Richmond, O. P. and R. Mac Ginty (2015). “Where now for the critique of the liberal peace?” Cooperation and Conflict 50(2): 171–189.

Richmond, O. P. and A. Mitchell, Eds. (2012). Hybrid forms of peace. From everyday agency to post-liberalism . Rethinking Peace and Conflict Studies. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Risse-Kappen, T. (1995). “Democratic peace—Warlike democracies? A social constructivist interpretation of the liberal argument.” European Journal of International Relations 1(4): 491–517.

Röling, B. V. A. (1973). Polemologie. Een inleiding in de wetenschap van oorlog en vrede . Assen: van Gorcum.

Ruddick, S. (1995). Maternal thinking: Toward a politics of peace . Boston: Beacon Press.

Russett, B. (1994). Grasping the democratic peace: Principles for a post-Cold War world . Princeton University Press.

Russett, B. and J. Oneal (2001). Triangulating peace. Democracy, interdependence and international organizations . New York and London: Norton.

Sabaratnam, M. (2011). “The liberal peace? A brief intellectual history of international conflict management, 1990–2010.” In A liberal peace? The problems and practices of peacebuilding . S. Campbell, D. Chandler, and M. Sabaratnam (Eds.). London: Zed Books: 13–30.

Sabaratnam, M. (2013). “Avatars of Eurocentrism in the critique of the liberal peace.” Security Dialogue 44(3): 259–278.

Sambanis, N. (2008). “Short- and long-term effects of United Nations peace operations.” The World Bank Economic Review 22(1): 9–32.

Schia, N. N. and J. Karlsrud (2013). “‘Where the rubber meets the road’: Friction sites and local-level peacebuilding in Haiti, Liberia and South Sudan.” International Peacekeeping 20(2): 233–248.

Schmitt, C. (2008 [1932]). The concept of the political: Expanded edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Selby, J. (2013). “The myth of liberal peace-building.” Conflict, Security & Development 13(1): 57–86.

Senghaas, D. (2004). Zum irdischen Frieden: Erkenntnisse und Vermutungen . Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Shinko, R. E. (2008). “Agonistic peace: A postmodern reading.” Millennium-Journal of International Studies 36(3): 473–491.

Stensrud, E. E. (2009). “New dilemmas in transitional justice: Lessons from the mixed courts in Sierra Leone and Cambodia.” Journal of Peace Research 46(1): 5–15.

Suurmond, J. and P. M. Sharma (2012). “Like yeast that leavens the dough? Community mediation as local infrastructure for peace in Nepal.” Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 7(3): 81–86.

Sylvester, C. (1994). “Empathetic cooperation: A feminist method for IR.” Millennium-Journal of International Studies 23(2): 315–334.

Tadjbakhsh, S. (2009). “Conflicted outcomes and values:(Neo) liberal peace in central Asia and Afghanistan.” International Peacekeeping 16(5): 635–651.

Tadjbakhsh, S., Ed. (2011). Rethinking the liberal peace: External models and local alternatives . London and New York: Routledge.

Tasew, B. (2009). “Metaphors of peace and violence in the folklore discourses of South-Western Ethiopia: A comparative study.” In Department of social and cultural anthropology . Amsterdam: VU University.

Tomz, M. and J. L. Weeks (2013). “Public opinion and the democratic peace.” American Political Science Review 107(4): 849–865

Tongeren, P. v., M. Brenk, et al. (2005). People building peace II, Successful stories of civil society . Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

van Leeuwen, M., W. Verkoren, et al. (2012). “Thinking beyond the liberal peace: From utopia to heterotopias.” Acta Politica 47(3): 292–316.

Van Tongeren, P., M. O. Ojielo, et al. (2012). “The evolving landscape of infrastructures for peace.” Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 7(3): 1–7.

Von Clausewitz, C. (1984 [1832]). On war. Indexed edition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Wallensteen, P. (2015a). Quality peace: Peacebuilding, victory and world order . Oxford University Press.

Webel, C. (2007). “Introduction: Toward a philosophy and metapsychology of peace.” In Handbook of peace and conflict studies . C. Webel and J. Galtung (Eds.). London and New York: Routledge: 3–13.

Zelizer, C. and R. A. Rubinstein (2009). Building peace: Practical reflections from the field . Sterling, VA: Kumarian Press.

Zizek, S. (2009). Violence: Six sideways reflections . London: Profile Books.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Gijsbert M. van Iterson Scholten

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gijsbert M. van Iterson Scholten .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

van Iterson Scholten, G.M. (2020). Peace in Peace Studies: Beyond the ‘Negative/Positive’ Divide. In: Visions of Peace of Professional Peace Workers. Rethinking Peace and Conflict Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27975-2_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27975-2_2

Published : 12 October 2019

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-27974-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-27975-2

eBook Packages : Political Science and International Studies Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

December 2, 2021

Peace Is More Than War’s Absence, and New Research Explains How to Build It

A new project measures ways to promote positive social relations among groups

By Peter T. Coleman , Allegra Chen-Carrel & Vincent Hans Michael Stueber

PeopleImages/Getty Images

Today, the misery of war is all too striking in places such as Syria, Yemen, Tigray, Myanmar and Ukraine. It can come as a surprise to learn that there are scores of sustainably peaceful societies around the world, ranging from indigenous people in the Xingu River Basin in Brazil to countries in the European Union. Learning from these societies, and identifying key drivers of harmony, is a vital process that can help promote world peace.

Unfortunately, our current ability to find these peaceful mechanisms is woefully inadequate. The Global Peace Index (GPI) and its complement the Positive Peace Index (PPI) rank 163 nations annually and are currently the leading measures of peacefulness. The GPI, launched in 2007 by the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), was designed to measure negative peace , or the absence of violence, destructive conflict, and war. But peace is more than not fighting. The PPI, launched in 2009, was supposed to recognize this and track positive peace , or the promotion of peacefulness through positive interactions like civility, cooperation and care.

Yet the PPI still has many serious drawbacks. To begin with, it continues to emphasize negative peace, despite its name. The components of the PPI were selected and are weighted based on existing national indicators that showed the “strongest correlation with the GPI,” suggesting they are in effect mostly an extension of the GPI. For example, the PPI currently includes measures of factors such as group grievances, dissemination of false information, hostility to foreigners, and bribes.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The index also lacks an empirical understanding of positive peace. The PPI report claims that it focuses on “positive aspects that create the conditions for a society to flourish.” However, there is little indication of how these aspects were derived (other than their relationships with the GPI). For example, access to the internet is currently a heavily weighted indicator in the PPI. But peace existed long before the internet, so is the number of people who can go online really a valid measure of harmony?

The PPI has a strong probusiness bias, too. Its 2021 report posits that positive peace “is a cross-cutting facilitator of progress, making it easier for businesses to sell.” A prior analysis of the PPI found that almost half the indicators were directly related to the idea of a “Peace Industry,” with less of a focus on factors found to be central to positive peace such as gender inclusiveness, equity and harmony between identity groups.

A big problem is that the index is limited to a top-down, national-level approach. The PPI’s reliance on national-level metrics masks critical differences in community-level peacefulness within nations, and these provide a much more nuanced picture of societal peace . Aggregating peace data at the national level, such as focusing on overall levels of inequality rather than on disparities along specific group divides, can hide negative repercussions of the status quo for minority communities.

To fix these deficiencies, we and our colleagues have been developing an alternative approach under the umbrella of the Sustaining Peace Project . Our effort has various components , and these can provide a way to solve the problems in the current indices. Here are some of the elements:

Evidence-based factors that measure positive and negative peace. The peace project began with a comprehensive review of the empirical studies on peaceful societies, which resulted in identifying 72 variables associated with sustaining peace. Next, we conducted an analysis of ethnographic and case study data comparing “peace systems,” or clusters of societies that maintain peace with one another, with nonpeace systems. This allowed us to identify and measure a set of eight core drivers of peace. These include the prevalence of an overarching social identity among neighboring groups and societies; their interconnections such as through trade or intermarriage; the degree to which they are interdependent upon one another in terms of ecological, economic or security concerns; the extent to which their norms and core values support peace or war; the role that rituals, symbols and ceremonies play in either uniting or dividing societies; the degree to which superordinate institutions exist that span neighboring communities; whether intergroup mechanisms for conflict management and resolution exist; and the presence of political leadership for peace versus war.

A core theory of sustaining peace . We have also worked with a broad group of peace, conflict and sustainability scholars to conceptualize how these many variables operate as a complex system by mapping their relationships in a causal loop diagram and then mathematically modeling their core dynamics This has allowed us to gain a comprehensive understanding of how different constellations of factors can combine to affect the probabilities of sustaining peace.

Bottom-up and top-down assessments . Currently, the Sustaining Peace Project is applying techniques such as natural language processing and machine learning to study markers of peace and conflict speech in the news media. Our preliminary research suggests that linguistic features may be able to distinguish between more and less peaceful societies. These methods offer the potential for new metrics that can be used for more granular analyses than national surveys.

We have also been working with local researchers from peaceful societies to conduct interviews and focus groups to better understand the in situ dynamics they believe contribute to sustaining peace in their communities. For example in Mauritius , a highly multiethnic society that is today one of the most peaceful nations in Africa, we learned of the particular importance of factors like formally addressing legacies of slavery and indentured servitude, taboos against proselytizing outsiders about one’s religion, and conscious efforts by journalists to avoid divisive and inflammatory language in their reporting.