Advertisement

Impact of online learning on student's performance and engagement: a systematic review

- Open access

- Published: 01 November 2024

- Volume 3 , article number 205 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Catherine Nabiem Akpen ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0007-2218-2254 1 ,

- Stephen Asaolu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7116-6468 1 ,

- Sunday Atobatele ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1947-2561 2 ,

- Hilary Okagbue ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3779-9763 1 &

- Sidney Sampson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5303-5475 2

3021 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The rapid shift to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly influenced educational practices worldwide and increased the use of online learning platforms. This systematic review examines the impact of online learning on student engagement and performance, providing a comprehensive analysis of existing studies. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline, a thorough literature search was conducted across different databases (PubMed, ScienceDirect, and JSTOR for articles published between 2019 and 2024. The review included peer-reviewed studies that assess student engagement and performance in online learning environments. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 18 studies were selected for detailed analysis. The analysis revealed varied impacts of online learning on student performance and engagement. Some studies reported improved academic performance due to the flexibility and accessibility of online learning, enabling students to learn at their own pace. However, other studies highlighted challenges such as decreased engagement and isolation, and reduced interaction with instructors and peers. The effectiveness of online learning was found to be influenced by factors such as the quality of digital tools, good internet, and student motivation. Maintaining student engagement remains a challenge, effective strategies to improve student engagement such as interactive elements, like discussion forums and multimedia resources, alongside adequate instructor-student interactions, were critical in improving both engagement and performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Exploring the Factors Affecting Student Academic Performance in Online Programs: A Literature Review

A meta-analysis addressing the relationship between self-regulated learning strategies and academic performance in online higher education

Online engagement and performance on formative assessments mediate the relationship between attendance and course performance

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Online learning also referred to as E-learning or remote learning is essentially a web-based program that gives learners access to knowledge or information whenever needed, regardless of their proximity to a location or time constraints [ 1 ]. This form of learning has been around for a while, it started in the late 1990s and it has advanced quickly. It has been considered a good choice, particularly for adult learners [ 2 ].

Online education promotes a student-centred approach, whereby students are expected to actively participate in the learning process. The digital tools used in online learning include interactive elements, computers, mobile devices, the internet, and other devices that allow students to receive and share knowledge [ 3 ]. Different types of online learning exist, such as microlearning, individualized learning, synchronous, asynchronous, blended, and massive open online courses [ 2 ]. Online learning offers several advantages to students, such as its adaptability to individual needs, ease, and flexibility in terms of involvement. With user-friendly online learning applications on their personal computers (PCs) or laptops, students can take part in their online courses from any convenient place, they can take specific courses with less time and location restrictions [ 4 ].

Learning experiences and academic success of students are some of the difficulties of online education [ 5 ]. Furthermore, while technology facilitates accessibility and ease of use of online learning platforms, it can also have restrictive effects, where many students struggle to gain internet access [ 6 ], in turn causes problems with participation and attendance in virtual classes, which makes it difficult to adopt online learning platforms [ 7 ]. Other issues with e-learning include educational policy, learning pedagogy, accessibility, affordability, and flexibility [ 8 ]. Many developing countries have substantial issues with reliable internet connection and access to digital devices, especially among economically backward children [ 9 ]. Maintaining student engagement in an online classroom can be more difficult than in a traditional face-to-face setting [ 10 ]. Even with all the advantages of online learning, there is reduced interaction between students and course facilitators. Another barrier to online learning is the lack of opportunities for human connection, which was thought to be essential for creating peer support and creating in-depth group discussions on the subject [ 11 ].

Over the past four years, COVID-19 has spread over the world, forcing schools to close, hence the pandemic compelled educators and learners at every level to swiftly adapt to online learning to curb the spread of the disease while ensuring continuous education [ 12 ]. The emergence of the pandemic rendered traditional face-to-face teaching and training methods unfeasible [ 13 ]. Some studies [ 14 , 15 , 16 ] acknowledged that the move to online learning was significant and sudden, but that it was also necessary to continue the learning process. This abrupt change sparked an argument regarding the standard of learning and satisfaction with learning among students [ 17 ].

While there are similarities between face-to-face (F2F) and online learning, they still differ in several ways [ 18 ], some of the similarities are: prerequisites for students include attendance, comprehension of the subject matter, turning in homework, and completion of group projects. The teachers still need to create curricula, enhance the quality of their instruction, respond to inquiries from students, inspire them to learn, and grade assignments [ 19 ]. One difference between online learning and F2F learning is the fact that online learning is student-centred and necessitates active learning while F2F learning is teacher-centred and demands passive learning from the student [ 19 ]. Another difference is teaching and learning has to happen at the same time and location in face-to-face learning, while online learning is not restricted by time or location [ 20 ]. Online learning allows teaching and learning to be done separately using internet-based information delivery systems [ 21 ].

Finding more efficient strategies to increase student engagement in online learning settings is necessary, as the absence of F2F interactions between students and instructors or among students continues to be a significant issue with online learning [ 20 ]. Student engagement has been defined as how involved or interested students appear to be in their learning and how connected they are to their classes, their institutions, and each other [ 22 ]. Engagement has been pointed out as a major dimension of students’ level and quality of learning, and is associated with improvement in their academic achievement, their persistence versus dropout, as well as their personal and cognitive development [ 23 ]. In an online setting, student engagement is equally crucial to their success and performance [ 24 ].

Change in learning delivery method is accompanied by inquiries when assessing whether online education is a practical replacement for traditional classroom instruction, cost–benefit evaluation, student experience, and student achievement are now being carefully considered [ 19 ]. This decision-making process will most likely continue if students seek greater learning opportunities and technological advances [ 19 ].

An individual's academic performance is significant to their success during their time in an educational institution [ 25 ], students' academic achievement is one indicator of their educational accomplishment. However, it is frequently seen that while student learning capacities are average, the demands placed on them for academic achievement are rising. This is the reason why the student's academic performance success rate is below par [ 25 ].

Numerous authors [ 11 , 13 , 18 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ] have examined how students and teachers view online learning, but it is still important to understand how much students are learning from these platforms. After all, student performance determines whether a subject or course is successful or unsuccessful.

The increase in the use of online learning calls for a careful analysis of its impact on student performance and engagement. Investigating the online learning experiences of students will guide education policymakers such as ministries, departments, and agencies in both the public and private sectors in the evaluation of the potential pros and cons of adopting online education against F2F education [ 30 ]

Given the foregoing, this study was carried out to; (1) investigate the online learning experiences of students, (2) review the academic performance of students using online learning platforms, and (3) explore the levels of students’ engagement when learning using online platforms.

2 Methodology

The study was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [ 31 ].

2.1 Search strategy and databases used

PubMed, ScienceDirect, and JSTOR were databases used to search for articles using identified search terms. The three data bases were selected for their extensive coverage of health sciences, social sciences and educational articles. The articles searched were between the years 2019–2024, this is because online learning became popular during the COVID-19 pandemic which started in 2019. Only English, open-access, and free full-text articles were selected for review, this is to ensure that the data analysed are publicly available to ascertain transparency and reproducibility of the review. The search was carried out in February 2024. The search strategy terms used are shown in Table 1 .

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles included for review were studies conducted on students enrolled in any field in a higher institution. Only articles in English language that were published between 2019 and 2024 which assessed student performance and engagement were included.

Articles excluded are studies involving pupils (students in primary school), articles not written in English language, and those published before 2019. Also, studies that did not follow the declaration of Helsinki on research ethics and without clear evidence of ethical consideration and approval were excluded.

2.3 Search outcomes

A total of 1078 articles were obtained from the databases searched. Four articles were duplicated and eliminated from the review. After the elimination of duplicates, titles, and abstracts were used to evaluate the remaining 1074 articles. These articles were screened based on the inclusion criteria, a total of 1052 studies were excluded after reading the titles and abstracts. Complete texts of 22 articles were read and four were found to be irrelevant to the review, a total of 18 articles were used for the systematic review.

The PRISMA flowchart shown in Fig. 1 illustrates the procedure used to screen and assess the articles.

A PRISMA flow chart of studies included in the systematic review

2.4 Data analysis

A data synthesis table was developed to collect relevant information on the author, year study was conducted, study design, study location, sample methodology, sample size, population, assessment tool, findings on student performance and student engagement, other findings, and limitations. Data was collected about whether students’ performance and engagement improved or declined following the introduction of online learning in their education. Data about the extent of the improvement or decline was also collected.

2.5 Quality appraisal

A quality assessment was carried out using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) developed to appraise systematic reviews. The checklist was used to analyse the included articles.

The characteristics of the 18 articles included in the study are presented in Table 2 . Ten (55.6%) were cross-sectional studies [ 2 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 29 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ], three (16.7%) were mixed methods studies [ 18 , 26 , 37 ], two (11.1%) were quasi-experimental and longitudinal studies [ 3 , 38 , 39 , 40 ], and one (5.5%) was a qualitative study [ 41 ].

The population involved in the study was a mix of students from various fields and departments, including medical, nursing, pharmacy, psychology, students taking management courses, and engineering students [ 3 , 12 , 13 , 18 , 29 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 38 , 39 , 41 ]. Other students were undergraduates from different fields that were not mentioned [ 2 , 10 , 26 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 40 ].

Study outcomes were categorized using three categories; student performance, student engagement, and studies that measured both student performance and engagement.

The summary of findings from the included studies are presented in Table 3 . Questionnaire surveys were mostly used across all the studies, however, one study used focus group discussions [ 41 ] and another study used a checklist to collect administrative data from student registers [ 40 ]. Study designs used in the included studies are cross-sectional, mixed methods, quasi-experimental, qualitative, and longitudinal. Studies were included from various countries across all six continents, countries in Asia constituted most of the studies (n = 7), Europe (n = 5), North America (n = 2), South America, Africa, and Australia all had one country represented in the study location.

3.1 Students’ performance

The impact of online learning on student performance was documented in thirteen studies [ 3 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 18 , 26 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]. In the study conducted by Elnour et al. [ 12 ], about half of the respondents strongly agreed that online learning had a negative impact on their grades in comparison to when they were attending face-to-face classes, two other studies had similar findings where students reported a decline in their grades during online learning [ 34 , 40 ].

Two studies experimented to compare grades achieved by students taking online classes (experimental group) with students taking face-to-face classes (control group) and found that those in the experimental group scored higher during examinations than those in the control group [ 38 , 39 ]. Nine studies included in this review showed a positive impact of online learning on student performance [ 3 , 10 , 13 , 26 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 38 , 39 ] students reported getting higher scores during examinations when they switched to online learning.

Two studies measured the performance of students before online learning and during online learning [ 3 , 40 ]. Both studies had varying findings, one of the studies found that when students started learning online, their grades improved on average from 4.7/10 to 5.15/10 and dropped to 4.6/10 when they went back to face-to-face learning [ 3 ], while another study used students' registers to capture their grades before online learning and when they started studying online and found that the switch to online learning led to a lesser number of credits obtained by the students [ 40 ].

3.2 Students’ engagement

Student engagement during online learning was reported in ten of the reviewed articles [ 2 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 18 , 29 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 41 ]. Students reported the negative effect of online learning on engagement with their peers and teachers. Nonetheless, in one of the studies [ 18 ], the respondents reported that online learning did not affect engagement with their lecturers, even though they felt least engaged with their peers. Students reported the effect of isolation when they were studying and taking classes online in comparison to when they had face-to-face learning [ 2 , 41 ], they revealed that the abrupt switch did not allow them to understand and adapt to the new form of learning and it led to feelings of isolation and separation from their classmates and teachers [ 2 ]

For science-based courses, students reported concern about carrying out practical classes, as studying online did not grant them the opportunity to effectively carry out practical [ 18 ]. Also, medical students reported dissatisfaction in interacting with their patients, which led to less engagement and connection [ 13 ]. One of the studies reviewed stated the role of engagement in increasing student performance over time, students stated that when they interact and engage with their teams and lecturers, they tend to perform better in their examinations [ 18 ].

4 Discussion

This study aimed to examine the impact of online learning on students' academic performance and engagement. The results underscore the varied impacts of online learning on student performance and engagement. While some students benefited from the flexibility and new opportunities presented by online learning, others struggled with the lack of direct interaction and practical engagement. This suggests that while online learning has potential, it requires careful implementation and support to address the challenges of engagement and practical application, particularly in fields requiring hands-on experience.

Majority of the articles in this review showed that online learning did not negatively affect the academic performance of students, though the studies did not have a standardized method of measuring their performance before online learning and during studying online, most of the survey was based on the students' perceptions. These findings support the findings of other studies that reported an increase in students' grades when they studied online [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Possible reasons highlighted for the increase in performance include the availability of recorded videos; students were able to study and listen to past teachings at their own pace and review course content when necessary. This enabled them to manage their time better and strengthen their understanding of complex materials and courses. Also, the use of computers and the availability of good internet connectivity were major reasons emphasized by students in helping them achieve good grades. The incorporation of digital tools like interactive quizzes, recorded videos, and learning management systems (LMS) provided students an interesting avenue to learn, which enhanced their academic performance [ 45 ]. Many students found that independent learning was suitable and matched their unique learning style better than F2F learning, this could be another reason for the improvement in their grades.

Despite reporting good grades with online learning, students still felt unsatisfied with this mode of learning, they reported bad internet connectivity, especially in studies conducted in Africa and Asia [ 1 , 13 ]. Furthermore, there were no academic performance variations between rural and urban learners [ 46 ], this finding varied with the finding of Bacher et al. [ 47 ] who stated that students in rural communities will require more support to bridge the academic gap experienced with their peers who live in urban settings. Another author compared the impact of environmental conditions at home and student academic performance, and it was found that students who had poor lighting conditions or those who were exposed to noisy environments performed poorly, this suggests that online learners need proper indoor lighting, ventilation, and a quiet environment for proper learning [ 42 ]

However, one of the studies found that online learning reduced the academic grades of the students, this could be because of the use of smartphones in carrying out examinations instead of using computers, and inexperience with the use of the Learning Management System (LMS) [ 34 ].

A lot of implications can arise as a result of improved performance among students due to a shift from F2F to online learning platforms. For students, it can increase confidence and contentment [ 48 ], but because of the dependence on technology, students also need to learn time management skills and self-discipline [ 49 ] which are essential for success in an online environment. Families may feel less stressed about their children’s academic success, but this might also result in more pressure to sustain these outcomes [ 50 ], particularly if the progress is linked directly to online learning. More educated citizens will benefit from increased academic performance through an increase in rates of employment and economic growth [ 51 ], but unequal access to technology could make the divide between various socioeconomic classes more pronounced. Furthermore, improved student performance has the potential to elevate the overall quality of the workforce, accelerating economic growth and competitiveness in the global market [ 52 ]. However, disparities in online learning must be addressed to guarantee that every student has an equal chance of success.

In terms of student engagement, similar findings were seen across the reviewed articles, most students reported that online learning was less engaging, and they could not associate with their peers or lecturers which made them feel self-isolated. This finding has been supported by Hollister et al. [ 43 ] where students complained of less engagement in online classes despite attaining good grades, they missed the spontaneous conversations and collaborations that are typical in a classroom setting. Motivation is an important element in both online and offline learning, students need self-motivation for overall learning outcomes [ 44 ]. Findings from this review indicate that students who reported being able to engage with their teams and lecturers actively attribute their success to self-motivation. Also, Cents-Boonstra et al. [ 53 ] investigated the role of motivating teaching behaviour and found that teachers who offered support and guidance during learning had more student engagement in comparison to teachers who did not offer any support or show enthusiasm for teaching. Courses that previously required hands-on experiences, like clinical practice or laboratory work, was challenging to conduct online, medical students expressed dissatisfaction with not being able to conduct practical sessions in the laboratory or interact effectively with their patients, this made learning online an isolating experience. Their participation dropped as a result of the separation between the theoretical and practical components of their education. This supports the finding of Khalil et al. [ 54 ] where medical students stated that they missed having live clinical sessions and couldn’t wait to go back to having a F2F class. Major barriers to participation included a lack of personal devices, and, inconsistent internet access, especially in rural or low-income areas. These barriers made it difficult for students to participate fully in online classes and also made them feel more frustrated and disengaged. This is similar to a study by Al-Amin et al. [ 11 ] where tertiary students studying online complained of less engagement in classroom activities.

Generally, students reported a negative effect of online learning on their engagement. This could be a result of poor technology skills, unavailability of personal computers or smartphones, or lack of internet services [ 55 ].

In a study conducted by Heilporn et al. [ 56 ], the author examined strategies that can be used by teachers to improve student engagement in a blended learning environment. Presenting a clear course structure and working at a particular pace, engaging learners with interactive activities, and providing additional support and constant feedback will help in improving overall student engagement. In a study by Gopal et al. [ 57 ], it was found that quality of instructor and the ability to use technological tools is an important element in influencing students engagement. The instructor needs to understand the psychology of the students in order to effectively present the course material.

A decrease in student engagement can have a detrimental effect on their entire educational experience, this can affect motivation and satisfaction. In the long-term, this could lead to decreased academic achievement and increased dropout rates [ 58 ]. To maintain students' motivation and engagement, families might need to put in extra effort especially if they simultaneously manage the online learning needs of numerous children [ 59 ]. This can result in additional stress or financial constraints in purchasing technological tools. In addition, for students studying online, it results in a less unified learning environment, which may diminish community bonds, and instructors will find it difficult to assist disengaged and potentially falling behind students [ 60 ].

The contrast between positive student performance and negative student engagement suggests that while online learning is a useful approach, it is less successful at fostering the interactive and social aspects of education. Online learning must include interactive components like discussion boards, and group projects that will enable in-person communication [ 61 ]. Furthermore, it is essential to guarantee that students have access to sufficient technology tools and training to enable them participate fully.

Some learners found it difficult to give the benefits of learning online, but none failed to give the benefits of face-to-face learning. In a study by Aguilera-Hermida [ 6 ], college students preferred studying in a physical classroom against studying online, they also found it hard to adapt to online classes, this decreased their level of participation and engagement. Also, an increase in good grades might be a result of cheating behaviours [ 3 ], given that unlike face-to-face learning where teachers are present to invigilate and validate that examinations were individual-based, for online learning it is difficult to determine if examinations were truly carried out by the students, giving students the option to share their answers with classmates or obtain them from internet resources. The studies did not state if measures were put in place to ensure exams taken online were devoid of cheating by the students.

Furthermore, online learning is here to stay, but there is a need for planning and execution of the process to mitigate the issue of students engaging effectively. Ignorance of this could put the possible advantages of this process in danger [ 62 ].

4.1 Limitations

A major limitation of this systematic review is the paucity of studies that objectively measured performance and engagement in students before and after the introduction of online learning. Findings in fourteen (78%) of the included articles were self-reported by the students which could lead to recall and/or desirability bias. In addition, the lack of uniform measurement or scale for assessing students’ performance and engagement is also a limitation. Subsequently, we suggest that standardized study tools should be developed and validated across various populations to more accurately and objectively evaluate the impact of the introduction of online learning on students’ performance and engagement. More studies should be conducted with clear pre- and post-intervention measurements using different pedagogical approaches to access their effects on students’ performance and engagement. These studies should also design ways of measuring indicators objectively without recall or desirability biases. Furthermore, the exclusion of studies that are not open access as well as publication bias for articles not published in English language are also limitations of this study.

5 Conclusion

The switch to online learning had both its advantages and disadvantages. The flexibility and accessibility of online platforms have played a major role in the enhancement of student performance, yet the decline in engagement underscores the need for more efficacious strategies to promote engagement. Online learning had a positive impact on student performance, most of the students reported either an increase or no change in grades when they changed to learning online. Only three studies stated a decline in student performance. Overall, students felt with online learning, they could not engage with their peers, teams, and teachers. They had a feeling of social isolation and felt more engagement would have improved their performance better. Schools and policymakers must develop strategies to mitigate the challenge of student engagement in online learning. This is necessary to prepare institutions for potential future pandemics which will compel reliance on online learning, this is critical for maintaining student satisfaction and overall learning outcomes.

In summary, online learning has the capacity to enhance academic achievement, but its effectiveness depends on effectively resolving the barriers associated with student involvement. Future studies should examine the long-term effects of online learning on student's performance and engagement with emphasis on creating strategies to improve the social and interactive components of the learning process. This is essential to guarantee that, in the future, online learning will be a viable and productive educational medium not just a band-aid fix during emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data availability

The articles used for this systematic review are all cited and publicly available.

Bossman A, Agyei SK. Technology and instructor dimensions, e-learning satisfaction, and academic performance of distance students in Ghana. Heliyon. 2022;8(4):09200. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2022.E09200 .

Article Google Scholar

Rahman A, Islam MS, Ahmed NAMF, Islam MM. Students’ perceptions of online learning in higher secondary education in Bangladesh during COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Sci Human Open. 2023;8(1):100646. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SSAHO.2023.100646 .

Pérez MA, Tiemann P, Urrejola-Contreras GP. The impact of the learning environment sudden shifts on students’ performance in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ Méd. 2023;24(3):100801. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EDUMED.2023.100801 .

Basar ZM, Mansor AN, Jamaludin KA, Alias BS. The effectiveness and challenges of online learning for secondary school students—a case study. Asian J Univ Educ. 2021;17(3):119–29.

Rajabalee YB, Santally MI. Learner satisfaction, engagement and performances in an online module: Implications for institutional e-learning policy. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr). 2021;26(3):2623–56.

Aguilera-Hermida AP. College students’ use and acceptance of emergency online learning due to COVID-19. Int J Educ Res Open. 2020;1:100011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100011 .

Nambiar D. The impact of online learning during COVID-19: students’ and teachers’ perspective. Int J Indian Psychol. 2020;8(2):783–93.

Google Scholar

Maheshwari M, Gupta AK, Goyal S. Transformation in higher education through e-learning: a shifting paradigm. Pac Bus Rev Int. 2021;13(8):49–63.

Pokhrel S, Chhetri R. A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. High Educ Future. 2021;8(1):133–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347631120983481 .

Kedia P, Mishra L. Exploring the factors influencing the effectiveness of online learning: a study on college students. Soc Sci Human Open. 2023;8(1):100559. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SSAHO.2023.100559 .

Al-Amin M, Al Zubayer A, Deb B, Hasan M. Status of tertiary level online class in Bangladesh: students’ response on preparedness, participation and classroom activities. Heliyon. 2021;7(1):e05943. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2021.E05943 .

Elnour AA, Abou Hajal A, Goaddar R, Elsharkawy N, Mousa S, Dabbagh N, Mohamad Al Qahtani M, Al Balooshi S, Othman Al Damook N, Sadeq A. Exploring the pharmacy students’ perspectives on off-campus online learning experiences amid COVID-19 crises: a cross-sectional survey. Saudi Pharm J. 2023;31(7):1339–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2023.05.024 .

Fahim A, Rana S, Haider I, Jalil V, Atif S, Shakeel S, Sethi A. From text to e-text: perceptions of medical, dental and allied students about e-learning. Heliyon. 2022;8(12):e12157. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2022.E12157 .

Henriksen D, Creely E, Henderson M. Folk pedagogies for teacher transitions: approaches to synchronous online learning in the wake of COVID-19. J Technol Teach Educ. 2020;28(2):201–9.

Zhu X, Chen B, Avadhanam RM, Shui H, Zhang RZ. Reading and connecting: using social annotation in online classes. Inf Learn Sci. 2020;121(5/6):261–71.

Bao W. COVID-19 and online teaching in higher education: a case study of Peking University. Hum Behav Emerg Technol. 2020;2(2):113–5.

Baber H. Determinants of students’ perceived learning outcome and satisfaction in online learning during the pandemic of COVID-19. J Educ Elearn Res. 2020;7(3):285–92.

Afzal F, Crawford L. Student’s perception of engagement in online project management education and its impact on performance: the mediating role of self-motivation. Proj Leadersh Soc. 2022;3:100057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plas.2022.100057 .

Paul J, Jefferson F. A comparative analysis of student performance in an online vs. face-to-face environmental science course from 2009 to 2016. Front Comput Sci. 2019;1:7.

Francescucci A, Rohani L. Exclusively synchronous online (VIRI) learning: the impact on student performance and engagement outcomes. J Mark Educ. 2019;41(1):60–9.

Pei L, Wu H. Does online learning work better than offline learning in undergraduate medical education? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Educ Online. 2019;24(1):1666538.

Thang SM, Mahmud N, Mohd Jaafar N, Ng LLS, Abdul Aziz NB. Online learning engagement among Malaysian primary school students during the covid-19 pandemic. Int J Innov Creat Change. 2022;16(2):302–26.

Ribeiro L, Rosário P, Núñez JC, Gaeta M, Fuentes S. “First-year students background and academic achievement: the mediating role of student engagement. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2669.

Muzammil M, Sutawijaya A, Harsasi M. Investigating student satisfaction in online learning: the role of student interaction and engagement in distance learning university. Turk Online J Distance Educ. 2020;21(Special Issue-IODL):88–96.

Mandasari B. The impact of online learning toward students’ academic performance on business correspondence course. EDUTEC. 2020;4(1):98–110.

Chen LH. Moving forward: international students’ perspectives of online learning experience during the pandemic. Int J Educ Res Open. 2023;5:100276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2023.100276 .

Wu YH, Chiang CP. Online or physical class for histology course: Which one is better? J Dent Sci. 2023;18(3):1295–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jds.2023.03.004 .

Salahshouri A, Eslami K, Boostani H, Zahiri M, Jahani S, Arjmand R, Heydarabadi AB, Dehaghi BF. The university students’ viewpoints on e-learning system during COVID-19 pandemic: the case of Iran. Heliyon. 2022;8(2):e08984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08984 .

Maqbool S, Farhan M, Abu Safian H, Zulqarnain I, Asif H, Noor Z, Yavari M, Saeed S, Abbas K, Basit J, Ur Rehman ME. Student’s perception of E-learning during COVID-19 pandemic and its positive and negative learning outcomes among medical students: a country-wise study conducted in Pakistan and Iran. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;82:104713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104713 .

Anderson T. Theories for learning with emerging technologies. In: Veletsianos G, editor. Emerging technologies in distance education. Athabasca: Athabasca University Press; 2010.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906 .

Weerarathna RS, Rathnayake NM, Pathirana UPGY, Weerasinghe DSH, Biyanwila DSP, Bogahage SD. Effect of E-learning on management undergraduates’ academic success during COVID-19: a study at non-state Universities in Sri Lanka. Heliyon. 2023;9(9):e19293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19293 .

Bossman A, Agyei SK. Technology and instructor dimensions, e-learning satisfaction, and academic performance of distance students in Ghana. Heliyon. 2022;8(4):e09200. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2022.E09200 .

Mushtaha E, Abu Dabous S, Alsyouf I, Ahmed A, Raafat AN. The challenges and opportunities of online learning and teaching at engineering and theoretical colleges during the pandemic. Ain Shams Eng J. 2022;13(6):101770. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ASEJ.2022.101770 .

Wester ER, Walsh LL, Arango-Caro S, Callis-Duehl KL. Student engagement declines in STEM undergraduates during COVID-19–driven remote learning. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2021;22(1):22.1.50. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v22i1.2385 .

Lemay DJ, Bazelais P, Doleck T. Transition to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput Hum Behav Rep. 2021;4:100130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100130 .

Briggs MA, Thornton C, McIver VJ, Rumbold PLS, Peart DJ. Investigation into the transition to online learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic, between new and continuing undergraduate students. J Hosp Leis Sport Tour Educ. 2023;32:100430. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JHLSTE.2023.100430 .

Nácher MJ, Badenes-Ribera L, Torrijos C, Ballesteros MA, Cebadera E. The effectiveness of the GoKoan e-learning platform in improving university students’ academic performance. Stud Educ Eval. 2021;70:101026. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.STUEDUC.2021.101026 .

Grønlien HK, Christoffersen TE, Ringstad Ø, Andreassen M, Lugo RG. A blended learning teaching strategy strengthens the nursing students’ performance and self-reported learning outcome achievement in an anatomy, physiology and biochemistry course—a quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;52:103046. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEPR.2021.103046 .

De Paola M, Gioia F, Scoppa V. Online teaching, procrastination and student achievement. Econ Educ Rev. 2023;94:102378. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECONEDUREV.2023.102378 .

Goodwin J, Kilty C, Kelly P, O’Donovan A, White S, O’Malley M. Undergraduate student nurses’ views of online learning. Teach Learn Nurs. 2022;17(4):398–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TELN.2022.02.005 .

Realyvásquez-Vargas A, Maldonado-Macías AA, Arredondo-Soto KC, Baez-Lopez Y, Carrillo-Gutiérrez T, Hernández-Escobedo G. The impact of environmental factors on academic performance of university students taking online classes during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Mexico. Sustainability. 2020;12(21):9194.

Hollister B, Nair P, Hill-Lindsay S, Chukoskie L. Engagement in online learning: student attitudes and behavior during COVID-19. Front Educ. 2022;7:851019. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.851019 .

Hsu HC, Wang CV, Levesque-Bristol C. Reexamining the impact of self-determination theory on learning outcomes in the online learning environment. Educ Inf Technol. 2019;24(3):2159–74.

Bradley VM. Learning Management System (LMS) use with online instruction. Int J Technol Educ. 2021;4(1):68–92.

Clark AE, Nong H, Zhu H, Zhu R. Compensating for academic loss: online learning and student performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. China Econ Rev. 2021;68:101629.

Bacher-Hicks A, Goodman J, Mulhern C. Inequality in household adaptation to schooling shocks: Covid-induced online learning engagement in real time. J Public Econ. 2021;193:1043451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104345 .

Liu YM, Hou YC. Effect of multi-disciplinary teaching on learning satisfaction, self-confidence level and learning performance in the nursing students. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;55:103128.

Gelles LA, Lord SM, Hoople GD, Chen DA, Mejia JA. Compassionate flexibility and self-discipline: Student adaptation to emergency remote teaching in an integrated engineering energy course during COVID-19. Educ Sci (Basel). 2020;10(11):304.

Deng Y, et al. Family and academic stress and their impact on students’ depression level and academic performance. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:869337. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.869337 .

Gunderson M, Oreopolous P. Returns to education in developed countries. In: The economics of education; 2020. p. 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815391-8.00003-3 .

Prasetyo PE, Kistanti NR. Human capital, institutional economics and entrepreneurship as a driver for quality & sustainable economic growth. Entrep Sustain Issues. 2020;7(4):2575. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2020.7.4(1) .

Cents-Boonstra M, Lichtwarck-Aschoff A, Denessen E, Aelterman N, Haerens L. Fostering student engagement with motivating teaching: an observation study of teacher and student behaviours. Res Pap Educ. 2021;36(6):754–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2020.1767184 .

Khalil R, Mansour AE, Fadda WA, et al. The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02208-z .

Werang BR, Leba SMR. Factors affecting student engagement in online teaching and learning: a qualitative case study. Qualitative Report. 2022;27(2):555–77. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2022.5165 .

Heilporn G, Lakhal S, Bélisle M. An examination of teachers’ strategies to foster student engagement in blended learning in higher education. Int J Educ Technol High Educ. 2021;18(1):25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00260-3 .

Gopal R, Singh V, Aggarwal A. Impact of online classes on the satisfaction and performance of students during the pandemic period of COVID 19. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr). 2021;26:6923–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10523-1 .

Schnitzler K, Holzberger D, Seidel T. All better than being disengaged: student engagement patterns and their relations to academic self-concept and achievement. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2021;36(3):627–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-020-00500-6 .

Roksa J, Kinsley P. The role of family support in facilitating academic success of low-income students. Res High Educ. 2019;60:415–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9517-z .

Antoni J. Disengaged and nearing departure: Students at risk for dropping out in the age of COVID-19. TUScholarShare Faculty/Researcher Works; 2020. https://doi.org/10.34944/dspace/396 .

Cavinato AG, Hunter RA, Ott LS, Robinson JK. Promoting student interaction, engagement, and success in an online environment. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2021;413:1513–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-021-03178-x .

Kumar S, Todd G. Effectiveness of online learning interventions on student engagement and academic performance amongst first-year students in allied health disciplines: a systematic review of the literature. Focus Health Prof Educ Multi-Prof J. 2022;23(3):36–55. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.668657139008083 .

Download references

The authors did not receive funding from any agency/institution for this research.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Sydani Institute for Research and Innovation, Sydani Group, Abuja, Nigeria

Catherine Nabiem Akpen, Stephen Asaolu & Hilary Okagbue

Sydani Group, Abuja, Nigeria

Sunday Atobatele & Sidney Sampson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

CNA, SOA, SA, and SS initiated the topic, CNA, HO and SOA searched and screened the articles, CNA, SOA, and HO conducted the data synthesis for the manuscript, CNA wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, CNA and SOA wrote the second draft of the manuscript, and SOA, HO and SA provided supervision. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stephen Asaolu .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests regarding this research work.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Akpen, C.N., Asaolu, S., Atobatele, S. et al. Impact of online learning on student's performance and engagement: a systematic review. Discov Educ 3 , 205 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00253-0

Download citation

Received : 18 July 2024

Accepted : 05 September 2024

Published : 01 November 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00253-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Online learning

- Student engagement

- Student performance

- Systematic review

- Literature review

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Persistence and Dropout in Higher Online Education: Review and Categorization of Factors

Umair uddin shaikh, zaheeruddin asif.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Edited by: Abdul Hameed Pitafi, Sir Syed University of Engineering and Technology, Pakistan

Reviewed by: J. Abbas, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China; Rao Muhammad Rashid, Bahria University, Pakistan; Sheena Pitafi, Bahria University, Karachi, Pakistan

*Correspondence: Umair Uddin Shaikh, [email protected]

† These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

This article was submitted to Organizational Psychology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Psychology

Received 2022 Mar 22; Accepted 2022 Apr 19; Collection date 2022.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

Online learning is becoming more popular with the maturity of social and educational technologies. In the COVID-19 era, it has become one of the most utilized ways to continue academic pursuits. Despite the ease and benefits offered by online classes, their completion rates are surprisingly low. Although several past studies focused on online dropout rates, institutions and course providers are still searching for a solution to this alarming problem. It is mainly because the previous studies have used divergent frameworks and approaches. Based on empirical research since 2001, this study presents a comprehensive review of factors by synthesizing them into a logically cohesive and integrative framework. Using different combinations of terms related to persistence and dropout, the authors explored various databases to form a pool of past research on the subject. This collection was also enhanced using the snowball approach. The authors only selected empirical, peer-reviewed, and contextually relevant studies, shortlisting them by reading through the abstracts. The Constant Comparative Method (CCM) seems ideal for this research. The authors employed axial coding to explore the relationships among factors, and selective coding helped identify the core categories. The categorical arrangement of factors will give researchers valuable insights into the combined effects of factors that impact persistence and dropout decisions. It will also direct future research to critically examine the relationships among factors and suggest improvements by validating them empirically. We anticipate that this research will enable future researchers to apply the results in different scenarios and contexts related to online learning.

Keywords: retention, persistence, attrition, dropout, online learning

Introduction

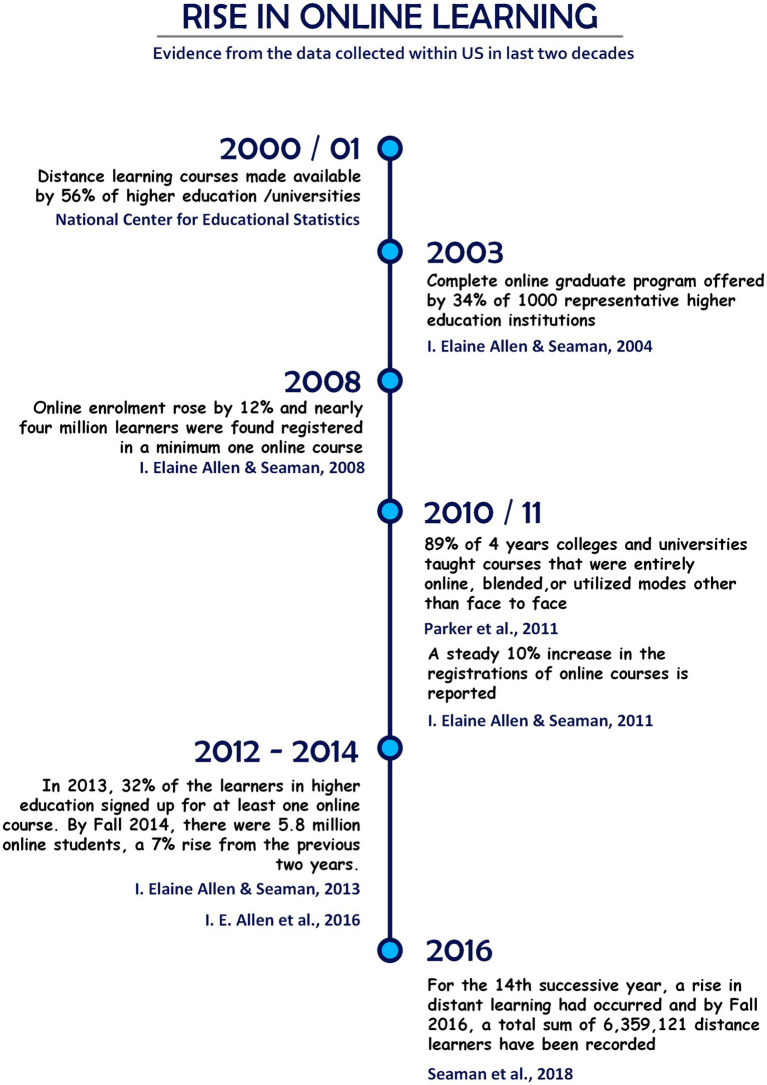

Higher education is increasingly embracing online courses ( Seaman et al., 2018 ; Johnson et al., 2019 ), mainly inspired by the demands of learners and budgetary constraints ( Limperos et al., 2015 ). The popularity of online courses in the United States has increased significantly over the last two decades (see Figure 1 ), and there was a total of 6,359,121 distance learners as of Fall 2016 ( Seaman et al., 2018 ). Similarly, more than 76% of colleges and universities in Canada offer online courses in 2019, and the proportion has risen to 92% of institutions with over 7,500 students and 93% of universities ( Johnson et al., 2019 ). Online classes are considered effective as their face-to-face counterparts ( Kumar et al., 2019 ). Students enroll in online courses to accomplish their own personal and professional goals. A greater degree of flexibility and unrestricted digital access to large volumes of information is compelling and accounts for the widespread popularity of enrolment in online courses ( Sitzmann et al., 2006 ; Zimmerman, 2012 ). Accessibility to online courses empowers learners to structure their classes alongside other family and work commitments, which may not be possible otherwise ( Lee, 2017 ). Also, the ongoing pandemic of COVID-19 has heavily impacted students, instructors, and educational organizations worldwide ( Almanthari et al., 2020 ). The instructors moved their courses online, and the students remained at home in response to social distancing measures ( Toquero, 2020 ). During these times, online learning became the most utilized way to continue academic activities globally, and experts began to consider it a viable alternative to face-to-face education ( Kaur, 2020 ). Higher education institutes quickly adopted the online delivery of education, incorporating media and technology ( Rahmat et al., 2022 ). They realized the need to develop and strengthen their capacity to achieve the desired results ( Maqsood et al., 2021 ).

Rise in online learning in the United States.

Problem Statement

Despite the massive growth, persistence rates of online courses are significantly low ( Xavier and Meneses, 2020 ) compared to those offered in person ( Muljana and Luo, 2019 ; Delnoij et al., 2020 ). Online learners struggle to complete their courses ( Friðriksdóttir, 2018 ) and attrition (or termination) is the leading problem encountered in many colleges ( Bowden, 2008 ), which is a foremost challenge for online education administrators/instructors ( Clay et al., 2008 ). The issue is still very challenging ( Chiyaka et al., 2016 ; Hobson and Puruhito, 2018 ; Johnson et al., 2019 ; Li and Wong, 2019 ). Only about 15% of Open Universities students leave with degrees or other qualifications, indicating a meager persistence rate among students taking online courses ( Mishra, 2017 ). Online dropout experience results in frustration and shatters learners’ confidence preventing future enrolments ( Poellhuber et al., 2008 ), which implies inadequacy, questionable quality, and profit loss for institutions ( Willging and Johnson, 2009 ; Gomez, 2013 ).

Research Motivation

Many researchers realized the need to minimize dropout rates of online learners as beneficial for students, institutes, and companies over time ( Lee and Choi, 2011 ; Wuellner, 2013 ; Garratt-Reed et al., 2016 ; Moore and Greenland, 2017 ; Murphy and Stewart, 2017 ). Additionally, the pandemic enforced utilization of technology in the learning process has made this vital topic of online learning more critical. Therefore, a need arises for further investigation into the quality of online learning ( Basilaia and Kvavadze, 2020 ) from a new and improved perspective.

Research Question

The decision to drop out does not always link to knowledge but may result from a lack of persistence. Persistence in online courses is considered a complex phenomenon influenced by many factors ( Yang et al., 2017 ; Choi and Park, 2018 ). Any single factor cannot predict student attrition from online courses ( Gaytan, 2013 ). It is imperative to study persistence on a large scale to understand better the factors that count toward online course completion or online learners’ decision to drop out ( Choi and Park, 2018 ). The following research question guides the literature review based on the rationale provided.

What factors are positively or negatively linked with persistence in post-secondary online education settings?

Persistence: Differing Definitions and Indicators

There is a problem with the non-standardized use of the term persistence in online courses. The authors either do not provide clear indicators for persistence or provide inconsistent definitions ( Lee and Choi, 2011 ). Some authors have described persistence as an inclination to complete the currently enrolled online course ( Joo et al., 2011 ; You, 2018 ), whereas others defined persistence as an intention to enroll in more online courses in the future or successfully concluding the course securing somewhere between A to C grade ( Lee and Choi, 2011 ). Intention to persist in the currently enrolled online course is considered the most referenced indicator of persistence ( Roland et al., 2018 ). We have relied on this exact definition in this study.

Research Background

Several authors have studied persistence factors related to online courses in post-secondary educational settings ( Gazza and Hunker, 2014 ; Muljana and Luo, 2019 ; Xavier and Meneses, 2020 ). These studies have used divergent approaches and frameworks, where authors have studied the factors in isolation. There exists a gap in the literature while analyzing the combined effect of factors on persistence and examining the impact of factors upon each other. To better understand the persistence or dropout phenomena, it is imperative to identify as many factors as possible and arrange them in their logical categories. In this study, we have reflected upon the factors that correlate positively (enablers) or negatively (barriers) to persistence in an integrative manner. This study contributes to the existing literature by presenting the organization of persistence/dropout factors, identified after a comprehensive literature review, as a logically cohesive and integrative framework. We believe our results would pave the way for future studies to consider the collective effect of factors on the persistence phenomena and the relationships among the factors. An overview of the methodological framework used to conduct the review and the process adopted for categorizing factors in their respective categories is discussed in the later section.

Methodological Framework

To understand the topic in-depth, we analyzed empirical studies published in peer-reviewed journals in the context of post-secondary education over the last two decades. Most of the review studies that focus on dropout/retention factors do not go beyond 10 years period. Ideally, the review on the subject should not miss any vital factor identified with the continuous evolution of the Internet, social, and educational technologies. This approach becomes significant when the intent is to arrange the factors into their logical categories and guide future studies to focus on the relationships among factors and their combined effect on persistence, while studying retention and dropout scenarios.

Selection Criteria

Initially, the search phase explored Education Research Complete, ProQuest, ERIC, JSTOR, and PsycInfo databases, using the terms “online,” “persistence,” “dropout,” “retention,” “attrition,” and “withdrawal” in various combinations. Further, we searched with the same terms on Google Scholar and applied the snowball technique to enhance the existing pool. The screening phase concluded by analyzing the abstracts. Duplicates, non-empirical, non-peer-reviewed, and out-of-context studies were excluded.

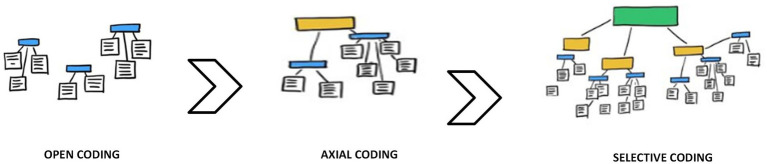

After identifying the related factors from the final list of studies, we applied Constant Comparative Method (CCM) of Glaser and Strauss (1967 , p. 102) to assign the factors into their logical categories. The constant comparative analysis is characterized by “explicit coding and analytic procedures.” Coding is the method of labeling and categorizing concepts. A concept can be viewed as a “basic unit of analysis” ( Corbin and Strauss, 1990 , p. 7). The formation of a category occurs when items with similar characteristics are grouped. There are three stages to coding: open, axial, and selective ( Corbin and Strauss, 1990 ). In open coding, an incident is compared with other incidents based on their similarity and differences, Incidents are given conceptual labels, and the concepts are grouped into categories ( Corbin and Strauss, 1990 ). Using axial coding, we explored the relationships between categories ( Strauss, 1987 ). Authors have used selective coding to form a core category or categories and build a story that connects them. A pictorial representation of the process is given in Figure 2 .

Pictorial representation of Constant Comparative Method (CCM).

Our basic units of analysis (concepts) are the 47 individual factors identified through the literature review. Initially, we selected one factor randomly to represent the first category. Then, the similarity of the randomly chosen second factor with the previous factor was evaluated. If that second factor was not found to be similar to the first, we created a new category to represent the second factor. Two authors from this study judged the similarity of the factors to form categories of logically cohesive factors within them. We also consulted a peer de-briefer (subject expert) to mediate some of the differences between the authors in the process of factor assignment to their respective categories. The open coding process continued, creating 13 categories containing 47 individual factors. In the axial coding stage, the relationships are evaluated among the formed categories, forming the three axes (core categories), having 5, 5, and 3 categories in each axis, respectively (see Table 1 ).

Summary of identified factors group wise.

Review Results

The scope of this review comprises a reflection of factors that correlate positively or negatively to persistence in post-secondary online settings. Prior research on persistence and dropouts has not been comprehensive and integrative, utilizing divergent frameworks and approaches. Moreover, the categorization presented in previous studies has not considered the importance of the relationship between factors. The contribution of this paper is 2-fold. Firstly, we have identified all the factors linked to persistence reported for the past 20 years. Secondly, we have presented a logically coherent and integrative framework to enable fellow researchers to examine and understand the relationships among the persistence factors in future studies. There is a definite need to study the exact relationships among the persistence factors ( Choi and Park, 2018 ). Therefore, we have focused on defining coherent categories of factors that can be used to analyze relationships among factors. Forming such categories can also provide essential insights for the institutes offering online courses, administrators of online programs, and course instructors/facilitators in improving retention and overall quality of online courses and programs.

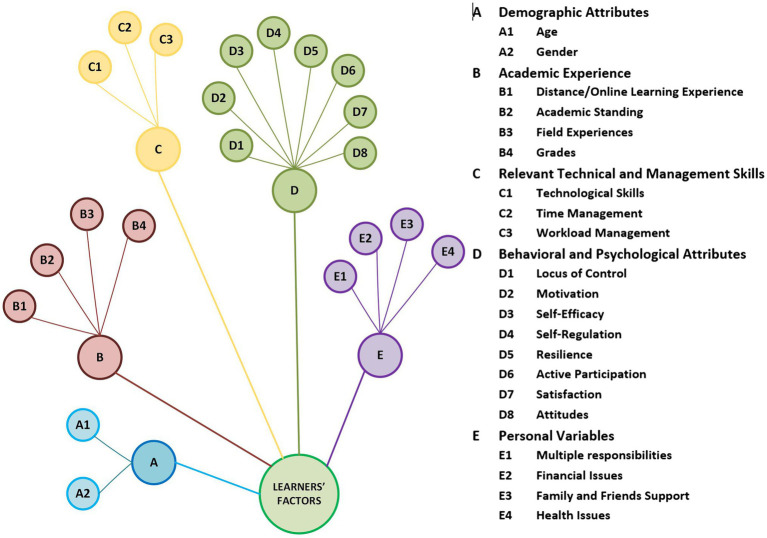

Persistence Factors Related to Online Learners

This section presents the factors related to online learners only. A review of these factors provides insights into the consensus among scholars, their differing views, and in some cases, contrasts empirical findings. The color-coded categorical arrangement of the factors related to online learners is presented in Figure 3 .

Categorical arrangement of factors related to online learners.

Demographic Attributes

Most researchers have focused on the differences in age and gender concerning persistence or dropout decisions made by the learner.

Some researchers reported no noteworthy difference in the age of students who drop out from online courses ( Levy, 2007 ; Tello, 2008 ; Willging and Johnson, 2009 ; James et al., 2016 ), while others have noted age as an important factor ( Xenos et al., 2002 ; Pierrakeas et al., 2004 ; Wladis et al., 2015 ; Murphy and Stewart, 2017 ). It has been posited that older students tend to drop out and require more encouragement from their teachers ( Xenos et al., 2002 ). Conversely, a retention study for online (STEM) courses reveals that older students showed better performance and had more likelihood of persistence ( Wladis et al., 2015 ). Similarly, James et al. (2016) stated that more senior students (age > 26) taking only online courses were retained more than younger students (age < 26). Also, Wuellner (2013) reported that younger learners might lack the skills and readiness required for online courses.

Some researchers believe that gender differences in online courses are not significantly related to retention/dropout ( Parker, 1999 ; Kemp, 2002 ; Cochran et al., 2014 ; Wladis et al., 2015 ; James et al., 2016 ). However, some studies informed the likelihood of the male population dropping from online courses ( Packham et al., 2004 ; Pocock et al., 2009 ). Studies also reveal that older female online learners get more influenced by the expectations around domestic and family responsibilities ( Dupin-Bryant, 2004 ; Stone and O’Shea, 2013 ).

Academic Experience

Some aspects of academic experiences are linked with persistence and dropping out decisions by online learners.

Distance/Online Learning Experience

Previous experience with distance or online learning improves awareness and boosts confidence. The number of previously done online courses ( Dupin-Bryant, 2004 ) and distant learning courses ( Levy, 2007 ; Traver et al., 2014 ) has been found to be linked with persistence decisions.

Academic Standing

Academic standing in college (freshman, sophomore, junior, or senior) is found to be related to persistence in online classes. Learners with higher status have increased chances of persistence ( Packham et al., 2004 ; Tello, 2008 ). However, Traver et al. (2014) has not found the academic year significant in predicting retention in online classes.

Field Experiences

While examining past educational and professional experiences of learners enrolled in an Informatics course online, Xenos et al. (2002) discovered that learners with prior backgrounds in programming or data handling showed significantly higher persistence rates. However, Cheung and Kan (2002) have not found previous experiences significant in persistence/dropout decisions.

Faculty and learners consider GPA and grades among the five most influential factors contributing to persistence/dropout decisions ( Gaytan, 2015 ). Many researchers have indicated that learners with lower academic scores are most likely to drop out of online classes ( Packham et al., 2004 ; Aragon and Johnson, 2008 ; Harrell and Bower, 2011 ; Xu and Jaggars, 2011 ; Colorado and Eberle, 2012 ; Stewart et al., 2013 ). Conversely, others have not found grades very significant in predicting retention/dropout ( Hachey et al., 2013 ; Traver et al., 2014 ; Shaw et al., 2016 ).

Relevant Technical and Management Skills

Previous research has focused on various technical and management skills of online learners that are found to be linked with persistence in online courses.

Technological Skills

Technological skills and confidence in using the computer, college readiness, and clarity of goals influence completing an online course ( Traver et al., 2014 ; Blau et al., 2016 ). The absence or lack of technical skills related to the Internet and its applications, operating systems, and file management is an important dropout indicator ( Dupin-Bryant, 2004 ). Similarly, Blau et al. (2016) found perceived ease of using technology is linked with persistence.

Time Management

While effective time management skills have been reported to influence persistence positively, learners’ difficulty in managing time has been strongly associated with early dropouts from online classes ( Ivankova and Stick, 2007 ; Stanford-Bowers, 2008 ; Nichols, 2010 ; Traver et al., 2014 ). Good study habits such as prioritizing tasks like assignments and making efficient use of available time enable learners to continue ( Castles, 2004 ; Ivankova and Stick, 2007 ). Aragon and Johnson (2008) supported this finding but noted a modest difference in the students’ capability enrolled in more online courses. The skill and ability to balance multiple responsibilities have been seen in those learners who complete their online courses ( Müller, 2008 ; Joo et al., 2011 ). Realistic expectations about the time and effort to complete a task are reported to facilitate better academic performance and completion of online courses ( Xenos et al., 2002 ; Wladis et al., 2015 ).

Workload Management

Online learners who actively plan to accommodate their workload are more likely to persist ( Bunn, 2004 ). Realistic expectations about the workload are noted as facilitators of persistence ( Leeds et al., 2013 ). An unexpected change in the workload of an online class is also reported as a dropout reason ( Moore and Greenland, 2017 ).

Behavioral and Psychological Attributes

Online learners’ behavioral and psychological characteristics encompass various attitudes and traits that shape their decision to persist or drop out.

Locus of Control

Thoughts about where to attribute outcomes of an event and the level of control over that subsequent event ( Rotter, 1966 ) is an individual’s locus of control. Lee and Choi (2013) found the locus of control as an influencing factor related to persistence. Individuals who have an “internal locus of control” tend to believe that the result of actions depends on their decisions and effort. Internal locus of control has been reported to link with persistence in online courses ( Parker, 2003 ; Morris et al., 2005b ).

It is the most significant force that shapes learners’ perceptions about enrolling in online classes and helps them persist ( Kemp, 2002 ; Holder, 2007 ; Blau et al., 2016 ). Motivation can positively forecast dropout decisions ( Osborn, 2001 ). Self-motivation, alongside personal challenge and responsibility, is considered the intrinsic motivation to conclude an online program ( Park and Choi, 2009 ; Nichols, 2010 ). Attachment and commitment toward a goal, goal attainment, respect for career, and financial outcomes of education are linked with persistence in online education ( Nichols, 2010 ; Joo et al., 2011 ). Self-determination helps to sustain learners in the online program ( Nichols, 2010 ).

Self-Efficacy

It is a “belief that one is capable of executing certain behaviors or achieving certain goals” ( Ormrod, 2011 , p. 352). Online student self-efficacy is identified as the most influential factor linked to retention ( Ivankova and Stick, 2007 ; Liaw, 2008 ; Street, 2010 ). A higher level of self-efficacy increases resilience in the cases of obstacles and intensifies learners’ efforts ( Kemp, 2002 ). Learners’ endurance to complete is associated with self-regulation and self-efficacy ( Gomez, 2013 ). Similarly, Ivankova and Stick (2007) and Ice et al. (2011) indicated a significant correlation between online course completion and self-efficacy.

Self-Regulation

It is an individual ability to control behavior, emotions, and thoughts in the engagement toward long-term goals. Those online learners who “self-regulate” successfully practice metacognitive, motivational, and behavioral processes as part of forethought, performance, and self-reflection ( Zimmerman, 2011 ). These behaviors generally include effective time management, seeking help from online course facilitators or tutoring, and avoiding distractions. Self-regulation influences learners’ persistence ( Gomez, 2013 ; Lee et al., 2013 ; O’Neill and Sai, 2014 ). Similarly, Lee et al. (2013) report meta-cognition as an influencing factor linked with retention. Self-discipline is also an influential factor contributing to persistence ( Gaytan, 2015 ).

An ability to manage threats during online courses has been an influencing factor differentiating persistent students from dropouts ( Parker, 1999 ; Müller, 2008 ).

Active Participation

Although a mild relationship exists between learner participation and academic success in terms of final grades ( Xia et al., 2013 ), online learners who actively interact with the course content are more likely to persist. Learners who complete their course view more discussion/content pages and spend more time viewing the discussions than those who withdraw ( Morris et al., 2005a ).

Satisfaction

Satisfaction with faculty and online courses has been found to be correlated with course completion in previous studies ( Tello, 2008 ; Joo et al., 2011 ).

Learners’ attitudes toward the course and their interactions with fellow peers and facilitators (instructors) are correlated with the completion of online courses ( Tello, 2008 ).

Personal Variables

Multiple responsibilities.

Family responsibilities are seen as a hindrance and a reason to withdraw from online learning in past studies ( Parkes et al., 2015 ; Shah and Cheng, 2019 ). Employment responsibilities also create problems for learners to continue ( Lee and Choi, 2011 ; Shah and Cheng, 2019 ), and part-time learners tend to drop out more from online classes ( Boston et al., 2011 ).

Financial Issues

Issues related to finance may contribute to dropout decisions by online learners ( Aversa and MacCall, 2013 ; Parkes et al., 2015 ). Online students usually pay the tuition fees out of pocket, and this added responsibility influences persistence decisions ( Boston et al., 2011 ). Contradictorily, Cochran et al. (2014) state that learners with loans/financial assistance are more inclined to drop out having certain major subjects.

Family and Friends Support

Family support and home environment is also significant factor related to persistence ( Harris et al., 2011 ). Non-persistent learners see friends and family as unsupportive in their educational journey ( Park and Choi, 2009 ). Learners who persist score higher in having supportive partners and maintaining healthy relationships ( Kemp, 2002 ).

Health Issues

Issues related to disability and health may also cause online learners to withdraw ( Shah and Cheng, 2019 ).

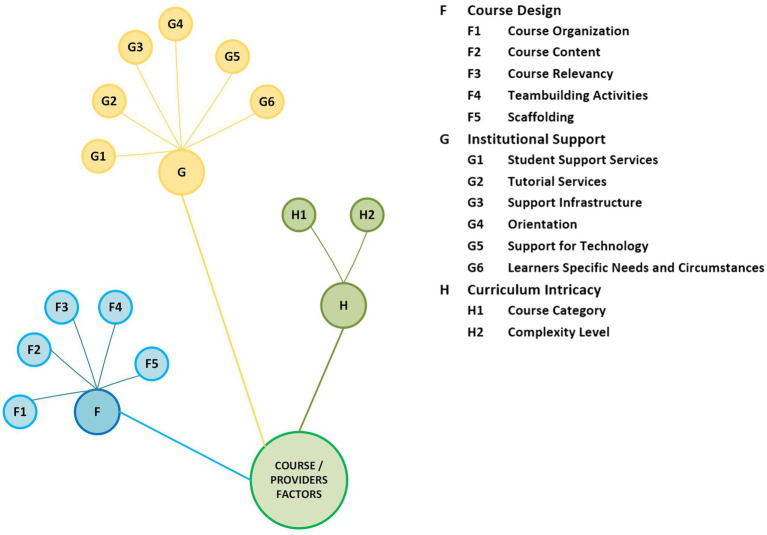

Persistence Factors Related to Online Courses and Course Providers

Factors linked with online course design and institutional support are listed in this section. This includes how the course or program is structured, the complexity of the curriculum, how the learners interact with the content, and what support services they perceive important. The color-coded categorical arrangement of the factors related to online courses and course providers is presented in Figure 4 .

Categorical arrangement of factors related to online courses and course providers.

Course Design

How the courses are defined and structured in terms of their interactivity, how well they fulfill the need of the learners, and the overall quality of online courses are important predictors of persistence and dropout.

Course Organization

Bad course organization, or at worst, lack of course organization and disconnected, illogical structures of the courses are linked with dropout decisions ( Hammond and Shoemaker, 2014 ). Ice et al. (2011) noted that poor course design/organization affects learner satisfaction, thus contributing to dropout decisions.

Course Content

Well-structured courses with rigorous, relevant content and clear instructions facilitate persistence ( Nichols, 2010 ; Harris et al., 2011 ), whereas boring and unrelated course elements promote dropout decisions ( Pittenger and Doering, 2010 ; Garratt-Reed et al., 2016 ).

Course Relevancy

Course relevancy with individuals’ learning styles and career objectives is important in shaping their decision to persist or withdraw from online courses ( Perry et al., 2008 ). Street (2010) also points out that relevant course factors and design impact learners’ choice to continue or drop out.

Team-Building Activities

Courses that promote team-building activities foster increased interaction between the learners and the faculty, thus contributing to increased retention ( Bocchi et al., 2004 ).

Scaffolding

An element of scaffolding fused into the course design forms striking, motivating, and related learning elements that enhance persistence ( Pittenger and Doering, 2010 ).

Institutional Support

Institutional support services have been confirmed crucial for online course completion by the administrators and faculty ( Heyman, 2010 ; Boston et al., 2011 ). However, learners do not perceive these support services as equally important ( Gaytan, 2015 ) but admit that the absence of these services negatively impacts their academic success ( Nichols, 2010 ).

Student Support Services

These services help learners overcome barriers that result in dropout decisions. Xu and Jaggers (2011) confirms that support services for online learners are not found as effective or satisfactory as they are for regular students. However, Muilenburg and Berge (2001) acknowledged unsatisfactory support services as barriers for online learners.

Tutorial Services

The academic and emotional support provided to online learners through face-to-face sessions improved persistence in online courses significantly ( Levy, 2007 ). Similarly, online learners perceive tutorials as helpful, encouraging them to continue ( Stanford-Bowers, 2008 ).

Support Infrastructure

Muilenburg and Berge (2001) conducted a factor analysis to study barriers related to distance education and identified a 10-factor model that deters course completion. Among these, five factors were found linked to institutional support infrastructure. These five factors are: (1) Structure of administration; (2) Student-support services; (3) Access; (4) Effectiveness and Evaluation; and (5) Teacher compensation and time. These factors were confirmed to influence distant learners’ dropping out decisions through telephonic interviews ( Clay et al., 2008 ; Nichols, 2010 ).

Orientation

Course orientation facilitates the chances of online learners persisting in the course ( Clay et al., 2008 ; Aversa and MacCall, 2013 ). Online advisory counseling and web orientation provided to undergraduates significantly increase the persistence rate ( Clay et al., 2008 ).

Support for Technology

Online learners possess different levels of skills related to computers and technology, and the perception of being unsupported is more of a problem than the actual struggle with technology ( Bunn, 2004 ). Parkes et al. (2015) exposed insufficient technology support to distant learners, impacting persistence ( Ojokheta, 2010 ; Street, 2010 ). However, Ivankova and Stick (2007) have not found technical support influential but agree that non-persistent learners were not pleased with the support services. Also, it is revealed that access issues with technology and the poor speed of the Internet may also influence dropout decisions ( Osborn, 2001 ).

Learners’ Specific Needs and Circumstances

Institutional lack of understanding of online learners’ needs and their specific circumstances contribute to dropout decisions ( Parkes et al., 2015 ; Friðriksdóttir, 2018 ).

Curriculum Intricacy

The category of an online course and its complexity level has been noted as influencing elements linked to learners’ persistence.

Course Category

The category of the course (elective, distribution, and major) and retention in online settings are interlinked ( Wladis et al., 2017 ). Additionally, Wladis et al. (2014) found lower-level STEM courses and dropout rates were positively associated.

Complexity Level

Online learners tend to drop out of online programs if there are many low-level and easy assignments or if they find the program curriculum too difficult ( Willging and Johnson, 2009 ). Similarly, Boston et al. (2011) posit that online learners were more inclined to drop out if they find the curriculum very easy or very difficult.

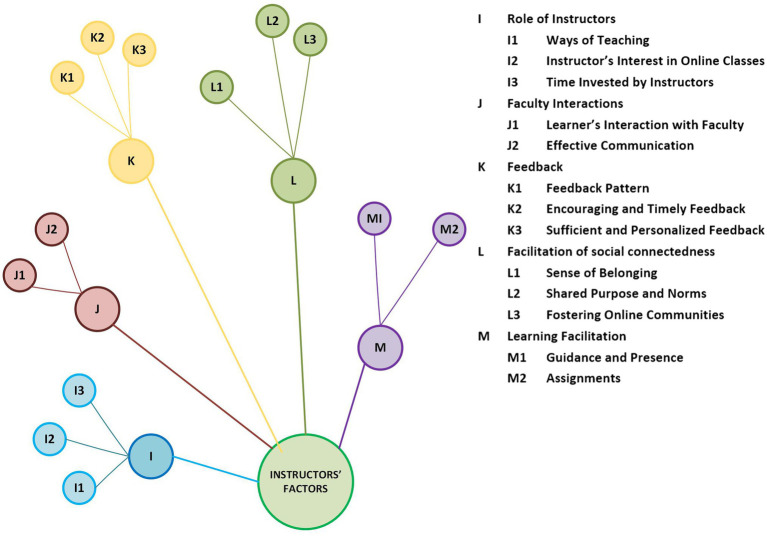

Persistence Factors Related to Online Instructors