Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples

Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples

Published on May 8, 2020 by Lauren Thomas . Revised on June 22, 2023.

In a longitudinal study, researchers repeatedly examine the same individuals to detect any changes that might occur over a period of time.

Longitudinal studies are a type of correlational research in which researchers observe and collect data on a number of variables without trying to influence those variables.

While they are most commonly used in medicine, economics, and epidemiology, longitudinal studies can also be found in the other social or medical sciences.

Table of contents

How long is a longitudinal study, longitudinal vs cross-sectional studies, how to perform a longitudinal study, advantages and disadvantages of longitudinal studies, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about longitudinal studies.

No set amount of time is required for a longitudinal study, so long as the participants are repeatedly observed. They can range from as short as a few weeks to as long as several decades. However, they usually last at least a year, oftentimes several.

One of the longest longitudinal studies, the Harvard Study of Adult Development , has been collecting data on the physical and mental health of a group of Boston men for over 80 years!

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

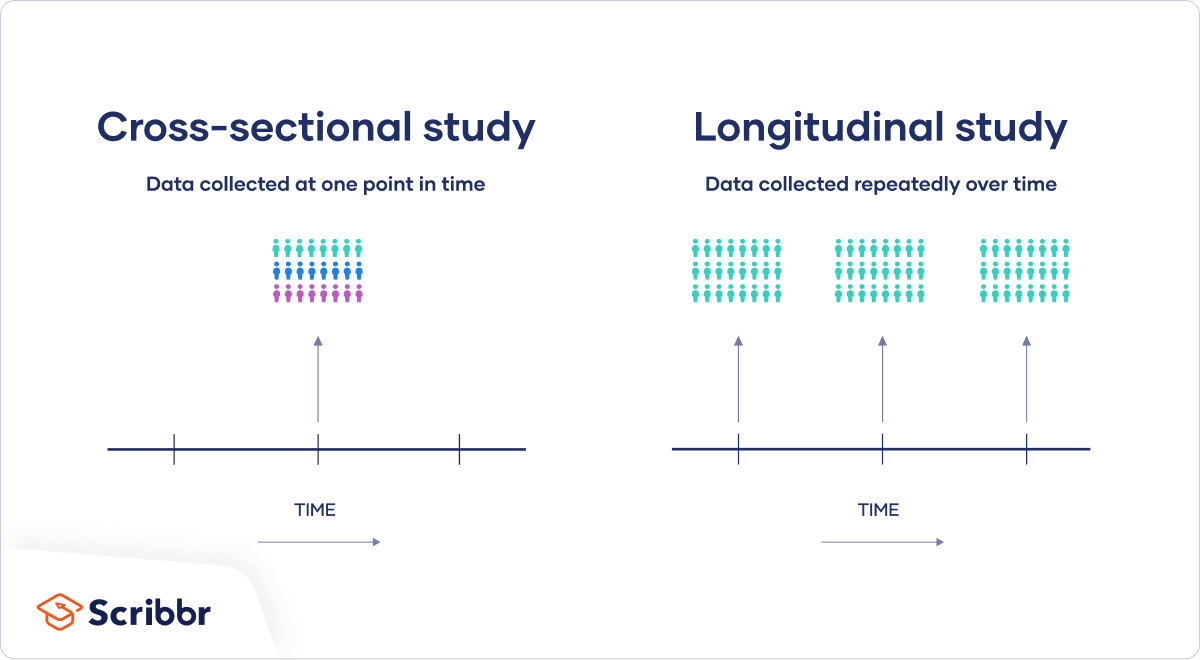

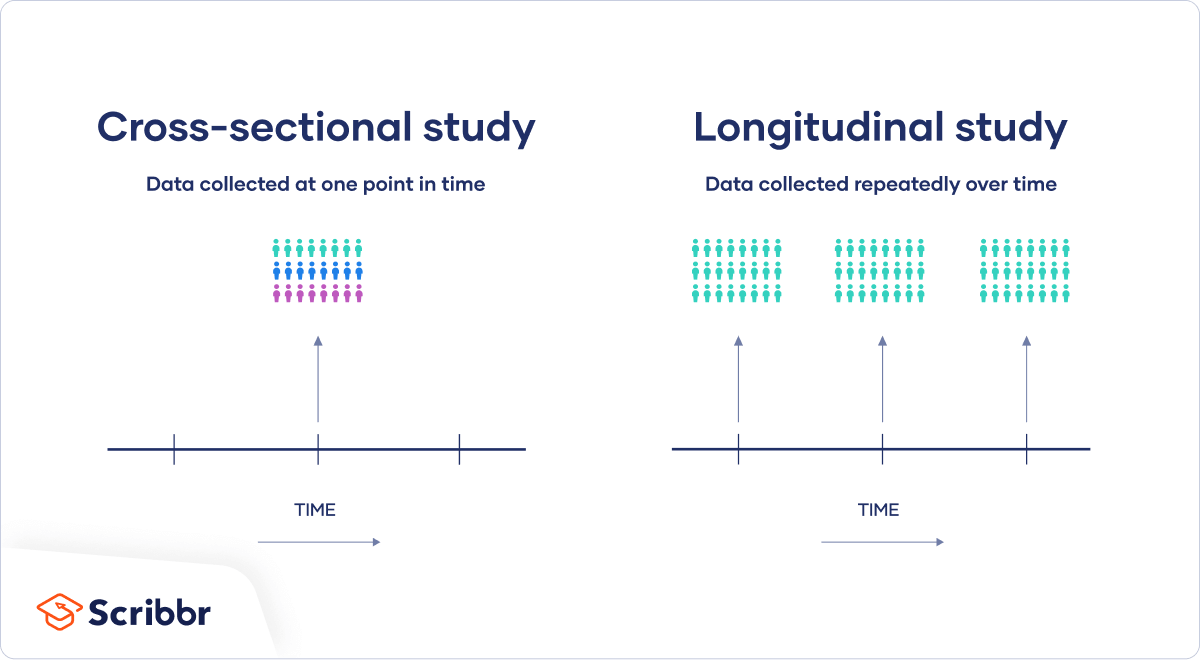

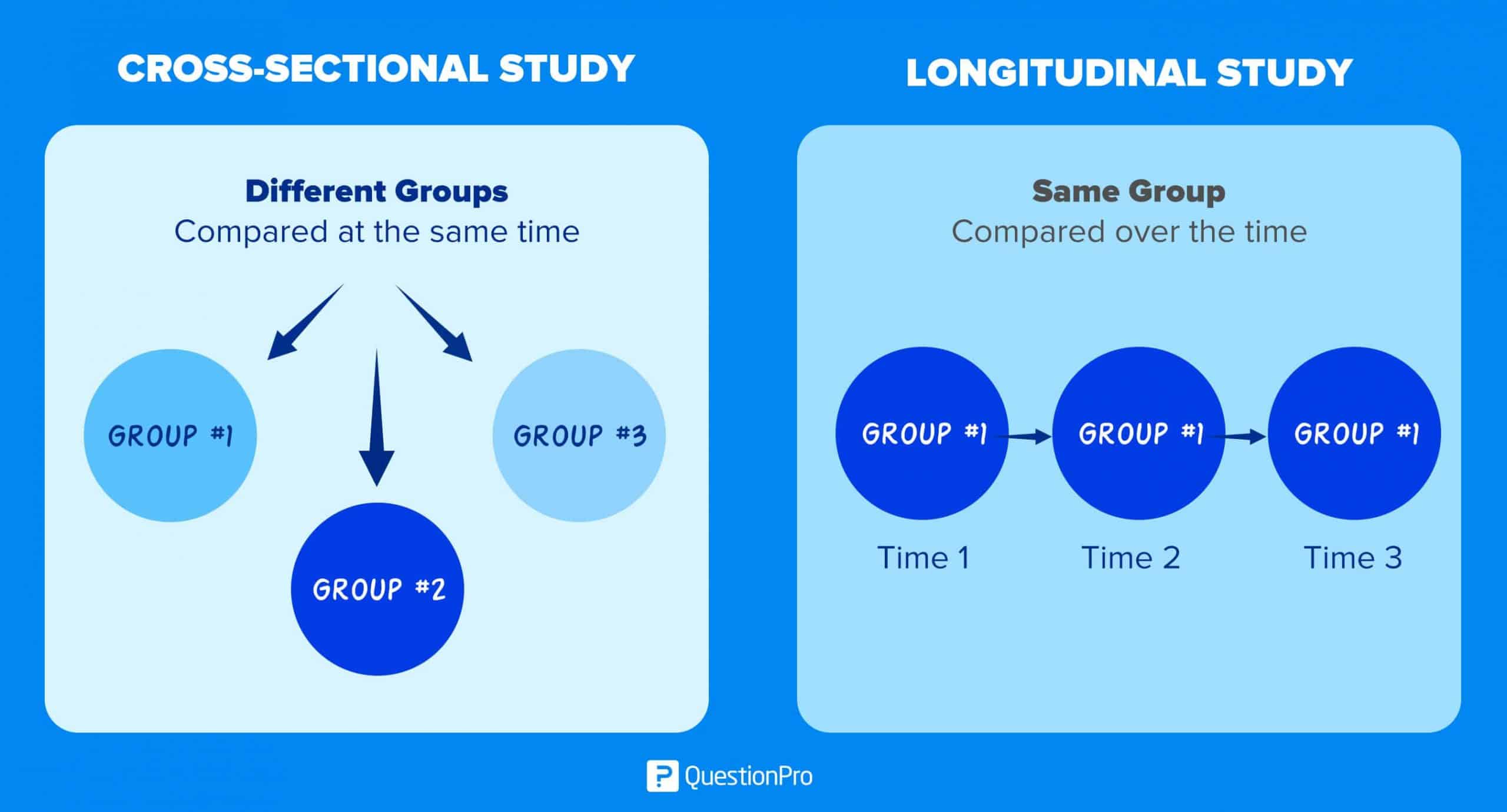

The opposite of a longitudinal study is a cross-sectional study. While longitudinal studies repeatedly observe the same participants over a period of time, cross-sectional studies examine different samples (or a “cross-section”) of the population at one point in time. They can be used to provide a snapshot of a group or society at a specific moment.

Both types of study can prove useful in research. Because cross-sectional studies are shorter and therefore cheaper to carry out, they can be used to discover correlations that can then be investigated in a longitudinal study.

If you want to implement a longitudinal study, you have two choices: collecting your own data or using data already gathered by somebody else.

Using data from other sources

Many governments or research centers carry out longitudinal studies and make the data freely available to the general public. For example, anyone can access data from the 1970 British Cohort Study, which has followed the lives of 17,000 Brits since their births in a single week in 1970, through the UK Data Service website .

These statistics are generally very trustworthy and allow you to investigate changes over a long period of time. However, they are more restrictive than data you collect yourself. To preserve the anonymity of the participants, the data collected is often aggregated so that it can only be analyzed on a regional level. You will also be restricted to whichever variables the original researchers decided to investigate.

If you choose to go this route, you should carefully examine the source of the dataset as well as what data is available to you.

Collecting your own data

If you choose to collect your own data, the way you go about it will be determined by the type of longitudinal study you choose to perform. You can choose to conduct a retrospective or a prospective study.

- In a retrospective study , you collect data on events that have already happened.

- In a prospective study , you choose a group of subjects and follow them over time, collecting data in real time.

Retrospective studies are generally less expensive and take less time than prospective studies, but are more prone to measurement error.

Like any other research design , longitudinal studies have their tradeoffs: they provide a unique set of benefits, but also come with some downsides.

Longitudinal studies allow researchers to follow their subjects in real time. This means you can better establish the real sequence of events, allowing you insight into cause-and-effect relationships.

Longitudinal studies also allow repeated observations of the same individual over time. This means any changes in the outcome variable cannot be attributed to differences between individuals.

Prospective longitudinal studies eliminate the risk of recall bias , or the inability to correctly recall past events.

Disadvantages

Longitudinal studies are time-consuming and often more expensive than other types of studies, so they require significant commitment and resources to be effective.

Since longitudinal studies repeatedly observe subjects over a period of time, any potential insights from the study can take a while to be discovered.

Attrition, which occurs when participants drop out of a study, is common in longitudinal studies and may result in invalid conclusions.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Longitudinal studies and cross-sectional studies are two different types of research design . In a cross-sectional study you collect data from a population at a specific point in time; in a longitudinal study you repeatedly collect data from the same sample over an extended period of time.

| Longitudinal study | Cross-sectional study |

|---|---|

| observations | Observations at a in time |

| Observes the multiple times | Observes (a “cross-section”) in the population |

| Follows in participants over time | Provides of society at a given point |

Longitudinal studies can last anywhere from weeks to decades, although they tend to be at least a year long.

Longitudinal studies are better to establish the correct sequence of events, identify changes over time, and provide insight into cause-and-effect relationships, but they also tend to be more expensive and time-consuming than other types of studies.

The 1970 British Cohort Study , which has collected data on the lives of 17,000 Brits since their births in 1970, is one well-known example of a longitudinal study .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Thomas, L. (2023, June 22). Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 21, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/longitudinal-study/

Is this article helpful?

Lauren Thomas

Other students also liked, cross-sectional study | definition, uses & examples, correlational research | when & how to use, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Longitudinal Study Design

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

A longitudinal study is a type of observational and correlational study that involves monitoring a population over an extended period of time. It allows researchers to track changes and developments in the subjects over time.

What is a Longitudinal Study?

In longitudinal studies, researchers do not manipulate any variables or interfere with the environment. Instead, they simply conduct observations on the same group of subjects over a period of time.

These research studies can last as short as a week or as long as multiple years or even decades. Unlike cross-sectional studies that measure a moment in time, longitudinal studies last beyond a single moment, enabling researchers to discover cause-and-effect relationships between variables.

They are beneficial for recognizing any changes, developments, or patterns in the characteristics of a target population. Longitudinal studies are often used in clinical and developmental psychology to study shifts in behaviors, thoughts, emotions, and trends throughout a lifetime.

For example, a longitudinal study could be used to examine the progress and well-being of children at critical age periods from birth to adulthood.

The Harvard Study of Adult Development is one of the longest longitudinal studies to date. Researchers in this study have followed the same men group for over 80 years, observing psychosocial variables and biological processes for healthy aging and well-being in late life (see Harvard Second Generation Study).

When designing longitudinal studies, researchers must consider issues like sample selection and generalizability, attrition and selectivity bias, effects of repeated exposure to measures, selection of appropriate statistical models, and coverage of the necessary timespan to capture the phenomena of interest.

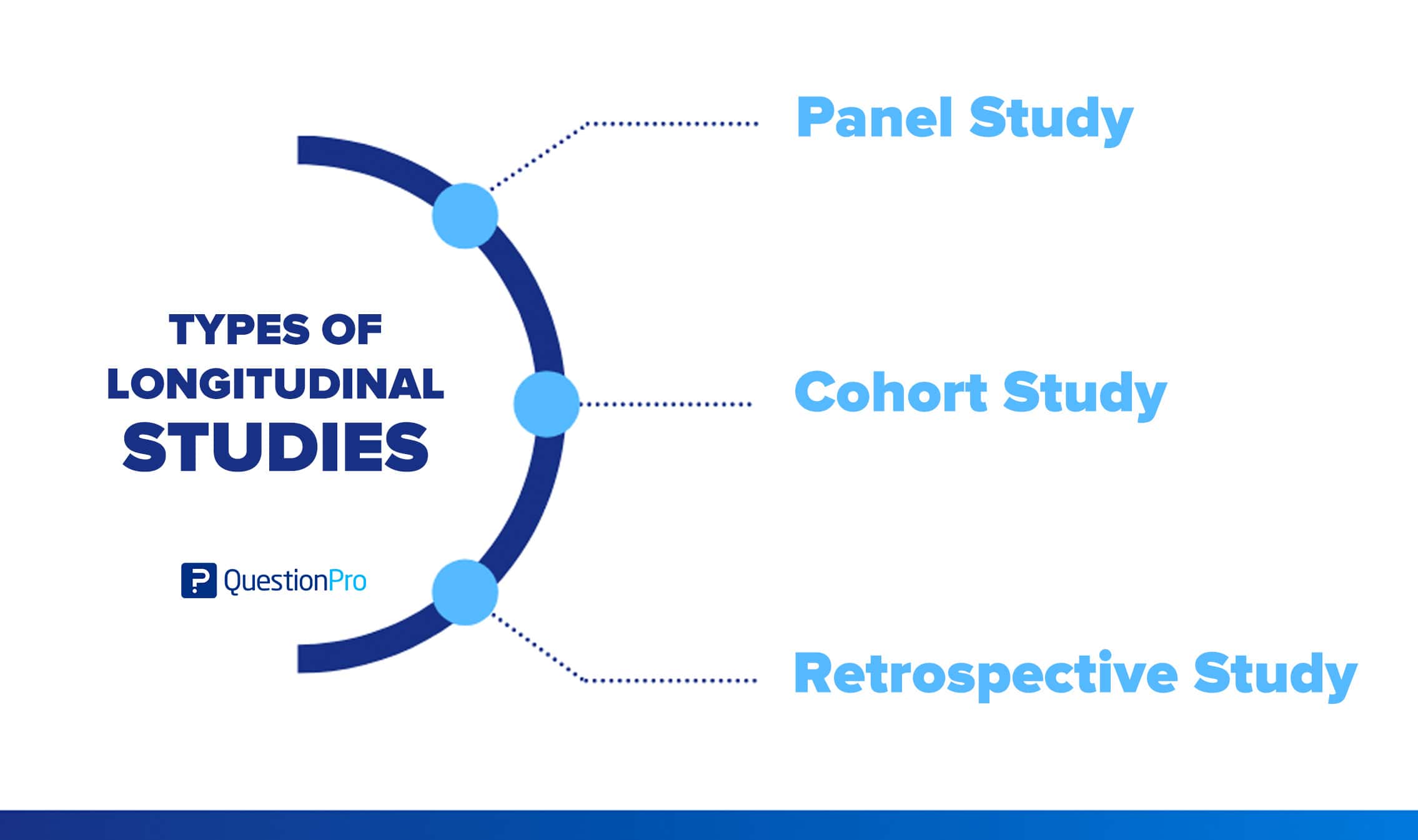

Panel Study

- A panel study is a type of longitudinal study design in which the same set of participants are measured repeatedly over time.

- Data is gathered on the same variables of interest at each time point using consistent methods. This allows studying continuity and changes within individuals over time on the key measured constructs.

- Prominent examples include national panel surveys on topics like health, aging, employment, and economics. Panel studies are a type of prospective study .

Cohort Study

- A cohort study is a type of longitudinal study that samples a group of people sharing a common experience or demographic trait within a defined period, such as year of birth.

- Researchers observe a population based on the shared experience of a specific event, such as birth, geographic location, or historical experience. These studies are typically used among medical researchers.

- Cohorts are identified and selected at a starting point (e.g. birth, starting school, entering a job field) and followed forward in time.

- As they age, data is collected on cohort subgroups to determine their differing trajectories. For example, investigating how health outcomes diverge for groups born in 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

- Cohort studies do not require the same individuals to be assessed over time; they just require representation from the cohort.

Retrospective Study

- In a retrospective study , researchers either collect data on events that have already occurred or use existing data that already exists in databases, medical records, or interviews to gain insights about a population.

- Appropriate when prospectively following participants from the past starting point is infeasible or unethical. For example, studying early origins of diseases emerging later in life.

- Retrospective studies efficiently provide a “snapshot summary” of the past in relation to present status. However, quality concerns with retrospective data make careful interpretation necessary when inferring causality. Memory biases and selective retention influence quality of retrospective data.

Allows researchers to look at changes over time

Because longitudinal studies observe variables over extended periods of time, researchers can use their data to study developmental shifts and understand how certain things change as we age.

High validation

Since objectives and rules for long-term studies are established before data collection, these studies are authentic and have high levels of validity.

Eliminates recall bias

Recall bias occurs when participants do not remember past events accurately or omit details from previous experiences.

Flexibility

The variables in longitudinal studies can change throughout the study. Even if the study was created to study a specific pattern or characteristic, the data collection could show new data points or relationships that are unique and worth investigating further.

Limitations

Costly and time-consuming.

Longitudinal studies can take months or years to complete, rendering them expensive and time-consuming. Because of this, researchers tend to have difficulty recruiting participants, leading to smaller sample sizes.

Large sample size needed

Longitudinal studies tend to be challenging to conduct because large samples are needed for any relationships or patterns to be meaningful. Researchers are unable to generate results if there is not enough data.

Participants tend to drop out

Not only is it a struggle to recruit participants, but subjects also tend to leave or drop out of the study due to various reasons such as illness, relocation, or a lack of motivation to complete the full study.

This tendency is known as selective attrition and can threaten the validity of an experiment. For this reason, researchers using this approach typically recruit many participants, expecting a substantial number to drop out before the end.

Report bias is possible

Longitudinal studies will sometimes rely on surveys and questionnaires, which could result in inaccurate reporting as there is no way to verify the information presented.

- Data were collected for each child at three-time points: at 11 months after adoption, at 4.5 years of age and at 10.5 years of age. The first two sets of results showed that the adoptees were behind the non-institutionalised group however by 10.5 years old there was no difference between the two groups. The Romanian orphans had caught up with the children raised in normal Canadian families.

- The role of positive psychology constructs in predicting mental health and academic achievement in children and adolescents (Marques Pais-Ribeiro, & Lopez, 2011)

- The correlation between dieting behavior and the development of bulimia nervosa (Stice et al., 1998)

- The stress of educational bottlenecks negatively impacting students’ wellbeing (Cruwys, Greenaway, & Haslam, 2015)

- The effects of job insecurity on psychological health and withdrawal (Sidney & Schaufeli, 1995)

- The relationship between loneliness, health, and mortality in adults aged 50 years and over (Luo et al., 2012)

- The influence of parental attachment and parental control on early onset of alcohol consumption in adolescence (Van der Vorst et al., 2006)

- The relationship between religion and health outcomes in medical rehabilitation patients (Fitchett et al., 1999)

Goals of Longitudinal Data and Longitudinal Research

The objectives of longitudinal data collection and research as outlined by Baltes and Nesselroade (1979):

- Identify intraindividual change : Examine changes at the individual level over time, including long-term trends or short-term fluctuations. Requires multiple measurements and individual-level analysis.

- Identify interindividual differences in intraindividual change : Evaluate whether changes vary across individuals and relate that to other variables. Requires repeated measures for multiple individuals plus relevant covariates.

- Analyze interrelationships in change : Study how two or more processes unfold and influence each other over time. Requires longitudinal data on multiple variables and appropriate statistical models.

- Analyze causes of intraindividual change: This objective refers to identifying factors or mechanisms that explain changes within individuals over time. For example, a researcher might want to understand what drives a person’s mood fluctuations over days or weeks. Or what leads to systematic gains or losses in one’s cognitive abilities across the lifespan.

- Analyze causes of interindividual differences in intraindividual change : Identify mechanisms that explain within-person changes and differences in changes across people. Requires repeated data on outcomes and covariates for multiple individuals plus dynamic statistical models.

How to Perform a Longitudinal Study

When beginning to develop your longitudinal study, you must first decide if you want to collect your own data or use data that has already been gathered.

Using already collected data will save you time, but it will be more restricted and limited than collecting it yourself. When collecting your own data, you can choose to conduct either a retrospective or prospective study .

In a retrospective study, you are collecting data on events that have already occurred. You can examine historical information, such as medical records, in order to understand the past. In a prospective study, on the other hand, you are collecting data in real-time. Prospective studies are more common for psychology research.

Once you determine the type of longitudinal study you will conduct, you then must determine how, when, where, and on whom the data will be collected.

A standardized study design is vital for efficiently measuring a population. Once a study design is created, researchers must maintain the same study procedures over time to uphold the validity of the observation.

A schedule should be maintained, complete results should be recorded with each observation, and observer variability should be minimized.

Researchers must observe each subject under the same conditions to compare them. In this type of study design, each subject is the control.

Methodological Considerations

Important methodological considerations include testing measurement invariance of constructs across time, appropriately handling missing data, and using accelerated longitudinal designs that sample different age cohorts over overlapping time periods.

Testing measurement invariance

Testing measurement invariance involves evaluating whether the same construct is being measured in a consistent, comparable way across multiple time points in longitudinal research.

This includes assessing configural, metric, and scalar invariance through confirmatory factor analytic approaches. Ensuring invariance gives more confidence when drawing inferences about change over time.

Missing data

Missing data can occur during initial sampling if certain groups are underrepresented or fail to respond.

Attrition over time is the main source – participants dropping out for various reasons. The consequences of missing data are reduced statistical power and potential bias if dropout is nonrandom.

Handling missing data appropriately in longitudinal studies is critical to reducing bias and maintaining power.

It is important to minimize attrition by tracking participants, keeping contact info up to date, engaging them, and providing incentives over time.

Techniques like maximum likelihood estimation and multiple imputation are better alternatives to older methods like listwise deletion. Assumptions about missing data mechanisms (e.g., missing at random) shape the analytic approaches taken.

Accelerated longitudinal designs

Accelerated longitudinal designs purposefully create missing data across age groups.

Accelerated longitudinal designs strategically sample different age cohorts at overlapping periods. For example, assessing 6th, 7th, and 8th graders at yearly intervals would cover 6-8th grade development over a 3-year study rather than following a single cohort over that timespan.

This increases the speed and cost-efficiency of longitudinal data collection and enables the examination of age/cohort effects. Appropriate multilevel statistical models are required to analyze the resulting complex data structure.

In addition to those considerations, optimizing the time lags between measurements, maximizing participant retention, and thoughtfully selecting analysis models that align with the research questions and hypotheses are also vital in ensuring robust longitudinal research.

So, careful methodology is key throughout the design and analysis process when working with repeated-measures data.

Cohort effects

A cohort refers to a group born in the same year or time period. Cohort effects occur when different cohorts show differing trajectories over time.

Cohort effects can bias results if not accounted for, especially in accelerated longitudinal designs which assume cohort equivalence.

Detecting cohort effects is important but can be challenging as they are confounded with age and time of measurement effects.

Cohort effects can also interfere with estimating other effects like retest effects. This happens because comparing groups to estimate retest effects relies on cohort equivalence.

Overall, researchers need to test for and control cohort effects which could otherwise lead to invalid conclusions. Careful study design and analysis is required.

Retest effects

Retest effects refer to gains in performance that occur when the same or similar test is administered on multiple occasions.

For example, familiarity with test items and procedures may allow participants to improve their scores over repeated testing above and beyond any true change.

Specific examples include:

- Memory tests – Learning which items tend to be tested can artificially boost performance over time

- Cognitive tests – Becoming familiar with the testing format and particular test demands can inflate scores

- Survey measures – Remembering previous responses can bias future responses over multiple administrations

- Interviews – Comfort with the interviewer and process can lead to increased openness or recall

To estimate retest effects, performance of retested groups is compared to groups taking the test for the first time. Any divergence suggests inflated scores due to retesting rather than true change.

If unchecked in analysis, retest gains can be confused with genuine intraindividual change or interindividual differences.

This undermines the validity of longitudinal findings. Thus, testing and controlling for retest effects are important considerations in longitudinal research.

Data Analysis

Longitudinal data involves repeated assessments of variables over time, allowing researchers to study stability and change. A variety of statistical models can be used to analyze longitudinal data, including latent growth curve models, multilevel models, latent state-trait models, and more.

Latent growth curve models allow researchers to model intraindividual change over time. For example, one could estimate parameters related to individuals’ baseline levels on some measure, linear or nonlinear trajectory of change over time, and variability around those growth parameters. These models require multiple waves of longitudinal data to estimate.

Multilevel models are useful for hierarchically structured longitudinal data, with lower-level observations (e.g., repeated measures) nested within higher-level units (e.g., individuals). They can model variability both within and between individuals over time.

Latent state-trait models decompose the covariance between longitudinal measurements into time-invariant trait factors, time-specific state residuals, and error variance. This allows separating stable between-person differences from within-person fluctuations.

There are many other techniques like latent transition analysis, event history analysis, and time series models that have specialized uses for particular research questions with longitudinal data. The choice of model depends on the hypotheses, timescale of measurements, age range covered, and other factors.

In general, these various statistical models allow investigation of important questions about developmental processes, change and stability over time, causal sequencing, and both between- and within-person sources of variability. However, researchers must carefully consider the assumptions behind the models they choose.

Longitudinal vs. Cross-Sectional Studies

Longitudinal studies and cross-sectional studies are two different observational study designs where researchers analyze a target population without manipulating or altering the natural environment in which the participants exist.

Yet, there are apparent differences between these two forms of study. One key difference is that longitudinal studies follow the same sample of people over an extended period of time, while cross-sectional studies look at the characteristics of different populations at a given moment in time.

Longitudinal studies tend to require more time and resources, but they can be used to detect cause-and-effect relationships and establish patterns among subjects.

On the other hand, cross-sectional studies tend to be cheaper and quicker but can only provide a snapshot of a point in time and thus cannot identify cause-and-effect relationships.

Both studies are valuable for psychologists to observe a given group of subjects. Still, cross-sectional studies are more beneficial for establishing associations between variables, while longitudinal studies are necessary for examining a sequence of events.

1. Are longitudinal studies qualitative or quantitative?

Longitudinal studies are typically quantitative. They collect numerical data from the same subjects to track changes and identify trends or patterns.

However, they can also include qualitative elements, such as interviews or observations, to provide a more in-depth understanding of the studied phenomena.

2. What’s the difference between a longitudinal and case-control study?

Case-control studies compare groups retrospectively and cannot be used to calculate relative risk. Longitudinal studies, though, can compare groups either retrospectively or prospectively.

In case-control studies, researchers study one group of people who have developed a particular condition and compare them to a sample without the disease.

Case-control studies look at a single subject or a single case, whereas longitudinal studies are conducted on a large group of subjects.

3. Does a longitudinal study have a control group?

Yes, a longitudinal study can have a control group . In such a design, one group (the experimental group) would receive treatment or intervention, while the other group (the control group) would not.

Both groups would then be observed over time to see if there are differences in outcomes, which could suggest an effect of the treatment or intervention.

However, not all longitudinal studies have a control group, especially observational ones and not testing a specific intervention.

Baltes, P. B., & Nesselroade, J. R. (1979). History and rationale of longitudinal research. In J. R. Nesselroade & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), (pp. 1–39). Academic Press.

Cook, N. R., & Ware, J. H. (1983). Design and analysis methods for longitudinal research. Annual review of public health , 4, 1–23.

Fitchett, G., Rybarczyk, B., Demarco, G., & Nicholas, J.J. (1999). The role of religion in medical rehabilitation outcomes: A longitudinal study. Rehabilitation Psychology, 44, 333-353.

Harvard Second Generation Study. (n.d.). Harvard Second Generation Grant and Glueck Study. Harvard Study of Adult Development. Retrieved from https://www.adultdevelopmentstudy.org.

Le Mare, L., & Audet, K. (2006). A longitudinal study of the physical growth and health of postinstitutionalized Romanian adoptees. Pediatrics & child health, 11 (2), 85-91.

Luo, Y., Hawkley, L. C., Waite, L. J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2012). Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: a national longitudinal study. Social science & medicine (1982), 74 (6), 907–914.

Marques, S. C., Pais-Ribeiro, J. L., & Lopez, S. J. (2011). The role of positive psychology constructs in predicting mental health and academic achievement in children and adolescents: A two-year longitudinal study. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 12( 6), 1049–1062.

Sidney W.A. Dekker & Wilmar B. Schaufeli (1995) The effects of job insecurity on psychological health and withdrawal: A longitudinal study, Australian Psychologist, 30: 1,57-63.

Stice, E., Mazotti, L., Krebs, M., & Martin, S. (1998). Predictors of adolescent dieting behaviors: A longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 12 (3), 195–205.

Tegan Cruwys, Katharine H Greenaway & S Alexander Haslam (2015) The Stress of Passing Through an Educational Bottleneck: A Longitudinal Study of Psychology Honours Students, Australian Psychologist, 50:5, 372-381.

Thomas, L. (2020). What is a longitudinal study? Scribbr. Retrieved from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/longitudinal-study/

Van der Vorst, H., Engels, R. C. M. E., Meeus, W., & Deković, M. (2006). Parental attachment, parental control, and early development of alcohol use: A longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20 (2), 107–116.

Further Information

- Schaie, K. W. (2005). What can we learn from longitudinal studies of adult development?. Research in human development, 2 (3), 133-158.

- Caruana, E. J., Roman, M., Hernández-Sánchez, J., & Solli, P. (2015). Longitudinal studies. Journal of thoracic disease, 7 (11), E537.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples

Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Lauren Thomas . Revised on 24 October 2022.

In a longitudinal study, researchers repeatedly examine the same individuals to detect any changes that might occur over a period of time.

Longitudinal studies are a type of correlational research in which researchers observe and collect data on a number of variables without trying to influence those variables.

While they are most commonly used in medicine, economics, and epidemiology, longitudinal studies can also be found in the other social or medical sciences.

Table of contents

How long is a longitudinal study, longitudinal vs cross-sectional studies, how to perform a longitudinal study, advantages and disadvantages of longitudinal studies, frequently asked questions about longitudinal studies.

No set amount of time is required for a longitudinal study, so long as the participants are repeatedly observed. They can range from as short as a few weeks to as long as several decades. However, they usually last at least a year, oftentimes several.

One of the longest longitudinal studies, the Harvard Study of Adult Development , has been collecting data on the physical and mental health of a group of men in Boston, in the US, for over 80 years.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

The opposite of a longitudinal study is a cross-sectional study. While longitudinal studies repeatedly observe the same participants over a period of time, cross-sectional studies examine different samples (or a ‘cross-section’) of the population at one point in time. They can be used to provide a snapshot of a group or society at a specific moment.

Both types of study can prove useful in research. Because cross-sectional studies are shorter and therefore cheaper to carry out, they can be used to discover correlations that can then be investigated in a longitudinal study.

If you want to implement a longitudinal study, you have two choices: collecting your own data or using data already gathered by somebody else.

Using data from other sources

Many governments or research centres carry out longitudinal studies and make the data freely available to the general public. For example, anyone can access data from the 1970 British Cohort Study, which has followed the lives of 17,000 Brits since their births in a single week in 1970, through the UK Data Service website .

These statistics are generally very trustworthy and allow you to investigate changes over a long period of time. However, they are more restrictive than data you collect yourself. To preserve the anonymity of the participants, the data collected is often aggregated so that it can only be analysed on a regional level. You will also be restricted to whichever variables the original researchers decided to investigate.

If you choose to go down this route, you should carefully examine the source of the dataset as well as what data are available to you.

Collecting your own data

If you choose to collect your own data, the way you go about it will be determined by the type of longitudinal study you choose to perform. You can choose to conduct a retrospective or a prospective study.

- In a retrospective study , you collect data on events that have already happened.

- In a prospective study , you choose a group of subjects and follow them over time, collecting data in real time.

Retrospective studies are generally less expensive and take less time than prospective studies, but they are more prone to measurement error.

Like any other research design , longitudinal studies have their trade-offs: they provide a unique set of benefits, but also come with some downsides.

Longitudinal studies allow researchers to follow their subjects in real time. This means you can better establish the real sequence of events, allowing you insight into cause-and-effect relationships.

Longitudinal studies also allow repeated observations of the same individual over time. This means any changes in the outcome variable cannot be attributed to differences between individuals.

Prospective longitudinal studies eliminate the risk of recall bias , or the inability to correctly recall past events.

Disadvantages

Longitudinal studies are time-consuming and often more expensive than other types of studies, so they require significant commitment and resources to be effective.

Since longitudinal studies repeatedly observe subjects over a period of time, any potential insights from the study can take a while to be discovered.

Attrition, which occurs when participants drop out of a study, is common in longitudinal studies and may result in invalid conclusions.

Longitudinal studies and cross-sectional studies are two different types of research design . In a cross-sectional study you collect data from a population at a specific point in time; in a longitudinal study you repeatedly collect data from the same sample over an extended period of time.

| Longitudinal study | Cross-sectional study |

|---|---|

| observations | Observations at a in time |

| Observes the multiple times | Observes (a ‘cross-section’) in the population |

| Follows in participants over time | Provides of society at a given point |

Longitudinal studies can last anywhere from weeks to decades, although they tend to be at least a year long.

The 1970 British Cohort Study , which has collected data on the lives of 17,000 Brits since their births in 1970, is one well-known example of a longitudinal study .

Longitudinal studies are better to establish the correct sequence of events, identify changes over time, and provide insight into cause-and-effect relationships, but they also tend to be more expensive and time-consuming than other types of studies.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Thomas, L. (2022, October 24). Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 21 August 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/longitudinal-study-design/

Is this article helpful?

Lauren Thomas

Other students also liked, correlational research | guide, design & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples.

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

Longitudinal Study: Overview, Examples & Benefits

By Jim Frost Leave a Comment

What is a Longitudinal Study?

A longitudinal study is an experimental design that takes repeated measurements of the same subjects over time. These studies can span years or even decades. Unlike cross-sectional studies , which analyze data at a single point, longitudinal studies track changes and developments, producing a more dynamic assessment.

A cohort study is a specific type of longitudinal study focusing on a group of people sharing a common characteristic or experience within a defined period.

Imagine tracking a group of individuals over time. Researchers collect data regularly, analyzing how specific factors evolve or influence outcomes. This method offers a dynamic view of trends and changes.

Consider a study tracking 100 high school students’ academic performances annually for ten years. Researchers observe how various factors like teaching methods, family background, and personal habits impact their academic growth over time.

Researchers frequently use longitudinal studies in the following fields:

- Psychology: Understanding behavioral changes.

- Sociology: Observing societal trends.

- Medicine: Tracking disease progression.

- Education: Assessing long-term educational outcomes.

Learn more about Experimental Designs: Definition and Types .

Duration of Longitudinal Studies

Typically, the objectives dictate how long researchers run a longitudinal study. Studies focusing on rapid developmental phases, like early childhood, might last a few years. On the other hand, exploring long-term trends, like aging, can span decades. The key is to align the duration with the research goals.

Implementing a Longitudinal Study: Your Options

When planning a longitudinal study, you face a crucial decision: gather new data or use existing datasets.

Option 1: Utilizing Existing Data

Governments and research centers often share data from their longitudinal studies. For instance, the U.S. National Longitudinal Surveys (NLS) has been tracking thousands of Americans since 1979, offering a wealth of data accessible through the Bureau of Labor Statistics .

This type of data is usually reliable, offering insights over extended periods. However, it’s less flexible than the data that the researchers can collect themselves. Often, details are aggregated to protect privacy, limiting analysis to broader regions. Additionally, the original study’s variables restrict you, and you can’t tailor data collection to meet your study’s needs.

If you opt for existing data, scrutinize the dataset’s origin and the available information.

Option 2: Collecting Data Yourself

If you decide to gather your own data, your approach depends on the study type: retrospective or prospective.

A retrospective longitudinal study focuses on past events. This type is generally quicker and less costly but more prone to errors.

The prospective form of this study tracks a subject group over time, collecting data as events unfold. This approach allows the researchers to choose the variables they’ll measure and how they’ll measure them. Usually, these studies produce the best data but are more expensive.

While retrospective studies save time and money, prospective studies, though more resource-intensive, offer greater accuracy.

Learn more about Retrospective and Prospective Studies .

Advantages of a Longitudinal Study

Longitudinal studies can provide insight into developmental phases and long-term changes, which cross-sectional studies might miss.

These studies can help you determine the sequence of events. By taking multiple observations of the same individuals over time, you can attribute changes to the other variables rather than differences between subjects. This benefit of having the subjects be their own controls is one that applies to all within-subjects studies, also known as repeated measures design. Learn more about Repeated Measures Designs .

Consider a longitudinal study examining the influence of a consistent reading program on children’s literacy development. In a longitudinal framework, factors like innate linguistic ability, which typically don’t fluctuate significantly, are inherently accounted for by using the same group of students over time. This approach allows for a more precise assessment of the reading program’s direct impact over the study’s duration.

Collectively, these benefits help you establish causal relationships. Consequently, longitudinal studies excel in revealing how variables change over time and identifying potential causal relationships .

Disadvantages of a Longitudinal Study

A longitudinal study can be time-consuming and expensive, given its extended duration.

For example, a 30-year study on the aging process may require substantial funding for decades and a long-term commitment from researchers and staff.

Over time, participants may selectively drop out, potentially skewing results and reducing the study’s effectiveness.

For instance, in a study examining the long-term effects of a new fitness regimen, more physically fit participants might be less likely to drop out than those finding the regimen challenging. This scenario potentially skews the results to exaggerate the program’s effectiveness.

Maintaining consistent data collection methods and standards over a long period can be challenging.

For example, a longitudinal study that began using face-to-face interviews might face consistency issues if it later shifts to online surveys, potentially affecting the quality and comparability of the responses.

In conclusion, longitudinal studies are powerful tools for understanding changes over time. While they come with challenges, their ability to uncover trends and causal relationships makes them invaluable in many fields. As with any research method, understanding their strengths and limitations is critical to effectively utilizing their potential.

Newman AB. An overview of the design, implementation, and analyses of longitudinal studies on aging . J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010 Oct;58 Suppl 2:S287-91. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02916.x. PMID: 21029055; PMCID: PMC3008590.

Share this:

Reader Interactions

Comments and questions cancel reply.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Longitudinal Study?

Tracking Variables Over Time

Steve McAlister / The Image Bank / Getty Images

The Typical Longitudinal Study

Potential pitfalls, frequently asked questions.

A longitudinal study follows what happens to selected variables over an extended time. Psychologists use the longitudinal study design to explore possible relationships among variables in the same group of individuals over an extended period.

Once researchers have determined the study's scope, participants, and procedures, most longitudinal studies begin with baseline data collection. In the days, months, years, or even decades that follow, they continually gather more information so they can observe how variables change over time relative to the baseline.

For example, imagine that researchers are interested in the mental health benefits of exercise in middle age and how exercise affects cognitive health as people age. The researchers hypothesize that people who are more physically fit in their 40s and 50s will be less likely to experience cognitive declines in their 70s and 80s.

Longitudinal vs. Cross-Sectional Studies

Longitudinal studies, a type of correlational research , are usually observational, in contrast with cross-sectional research . Longitudinal research involves collecting data over an extended time, whereas cross-sectional research involves collecting data at a single point.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers recruit participants who are in their mid-40s to early 50s. They collect data related to current physical fitness, exercise habits, and performance on cognitive function tests. The researchers continue to track activity levels and test results for a certain number of years, look for trends in and relationships among the studied variables, and test the data against their hypothesis to form a conclusion.

Examples of Early Longitudinal Study Design

Examples of longitudinal studies extend back to the 17th century, when King Louis XIV periodically gathered information from his Canadian subjects, including their ages, marital statuses, occupations, and assets such as livestock and land. He used the data to spot trends over the years and understand his colonies' health and economic viability.

In the 18th century, Count Philibert Gueneau de Montbeillard conducted the first recorded longitudinal study when he measured his son every six months and published the information in "Histoire Naturelle."

The Genetic Studies of Genius (also known as the Terman Study of the Gifted), which began in 1921, is one of the first studies to follow participants from childhood into adulthood. Psychologist Lewis Terman's goal was to examine the similarities among gifted children and disprove the common assumption at the time that gifted children were "socially inept."

Types of Longitudinal Studies

Longitudinal studies fall into three main categories.

- Panel study : Sampling of a cross-section of individuals

- Cohort study : Sampling of a group based on a specific event, such as birth, geographic location, or experience

- Retrospective study : Review of historical information such as medical records

Benefits of Longitudinal Research

A longitudinal study can provide valuable insight that other studies can't. They're particularly useful when studying developmental and lifespan issues because they allow glimpses into changes and possible reasons for them.

For example, some longitudinal studies have explored differences and similarities among identical twins, some reared together and some apart. In these types of studies, researchers tracked participants from childhood into adulthood to see how environment influences personality , achievement, and other areas.

Because the participants share the same genetics , researchers chalked up any differences to environmental factors . Researchers can then look at what the participants have in common and where they differ to see which characteristics are more strongly influenced by either genetics or experience. Note that adoption agencies no longer separate twins, so such studies are unlikely today. Longitudinal studies on twins have shifted to those within the same household.

As with other types of psychology research, researchers must take into account some common challenges when considering, designing, and performing a longitudinal study.

Longitudinal studies require time and are often quite expensive. Because of this, these studies often have only a small group of subjects, which makes it difficult to apply the results to a larger population.

Selective Attrition

Participants sometimes drop out of a study for any number of reasons, like moving away from the area, illness, or simply losing motivation . This tendency, known as selective attrition , shrinks the sample size and decreases the amount of data collected.

If the final group no longer reflects the original representative sample , attrition can threaten the validity of the experiment. Validity refers to whether or not a test or experiment accurately measures what it claims to measure. If the final group of participants doesn't represent the larger group accurately, generalizing the study's conclusions is difficult.

The World’s Longest-Running Longitudinal Study

Lewis Terman aimed to investigate how highly intelligent children develop into adulthood with his "Genetic Studies of Genius." Results from this study were still being compiled into the 2000s. However, Terman was a proponent of eugenics and has been accused of letting his own sexism , racism , and economic prejudice influence his study and of drawing major conclusions from weak evidence. However, Terman's study remains influential in longitudinal studies. For example, a recent study found new information on the original Terman sample, which indicated that men who skipped a grade as children went on to have higher incomes than those who didn't.

A Word From Verywell

Longitudinal studies can provide a wealth of valuable information that would be difficult to gather any other way. Despite the typical expense and time involved, longitudinal studies from the past continue to influence and inspire researchers and students today.

A longitudinal study follows up with the same sample (i.e., group of people) over time, whereas a cross-sectional study examines one sample at a single point in time, like a snapshot.

A longitudinal study can occur over any length of time, from a few weeks to a few decades or even longer.

That depends on what researchers are investigating. A researcher can measure data on just one participant or thousands over time. The larger the sample size, of course, the more likely the study is to yield results that can be extrapolated.

Piccinin AM, Knight JE. History of longitudinal studies of psychological aging . Encyclopedia of Geropsychology. 2017:1103-1109. doi:10.1007/978-981-287-082-7_103

Terman L. Study of the gifted . In: The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation. 2018. doi:10.4135/9781506326139.n691

Sahu M, Prasuna JG. Twin studies: A unique epidemiological tool . Indian J Community Med . 2016;41(3):177-182. doi:10.4103/0970-0218.183593

Almqvist C, Lichtenstein P. Pediatric twin studies . In: Twin Research for Everyone . Elsevier; 2022:431-438.

Warne RT. An evaluation (and vindication?) of Lewis Terman: What the father of gifted education can teach the 21st century . Gifted Child Q. 2018;63(1):3-21. doi:10.1177/0016986218799433

Warne RT, Liu JK. Income differences among grade skippers and non-grade skippers across genders in the Terman sample, 1936–1976 . Learning and Instruction. 2017;47:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.10.004

Wang X, Cheng Z. Cross-sectional studies: Strengths, weaknesses, and recommendations . Chest . 2020;158(1S):S65-S71. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.012

Caruana EJ, Roman M, Hernández-Sánchez J, Solli P. Longitudinal studies . J Thorac Dis . 2015;7(11):E537-E540. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.10.63

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

What is a longitudinal study?

Last updated

20 February 2023

Reviewed by

Longitudinal studies are common in epidemiology, economics, and medicine. People also use them in other medical and social sciences, such as to study customer trends. Researchers periodically observe and collect data from the variables without manipulating the study environment.

A company may conduct a tracking study, surveying a target audience to measure changes in attitudes and behaviors over time. The collected data doesn't change, and the time interval remains consistent. This longitudinal study can measure brand awareness, customer satisfaction , and consumer opinions and analyze the impact of an advertising campaign.

Analyze longitudinal studies

Dovetail streamlines longitudinal study data to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- Types of longitudinal studies

There are two types of longitudinal studies: Cohort and panel studies.

Panel study

A panel study is a type of longitudinal study that involves collecting data from a fixed number of variables at regular but distant intervals. Researchers follow a group or groups of people over time. Panel studies are designed for quantitative analysis but are also usable for qualitative analysis .

A panel study may research the causes of age-related changes and their effects. Researchers may measure the health markers of a group over time, such as their blood pressure, blood cholesterol, and mental acuity. Then, they can compare the scores to understand how age positively or negatively correlates with these measures.

Cohort study

A cohort longitudinal study involves gathering information from a group of people with something in common, such as a specific trait or experience of the same event. The researchers observe behaviors and other details of the group over time. Unlike panel studies, you can pick a different group to test in cohort studies.

An example of a cohort study could be a drug manufacturer studying the effects on a group of users taking a new drug over a period. A drinks company may want to research consumers with common characteristics, like regular purchasers of sugar-free sodas. This will help the company understand trends within its target market.

- Benefits of longitudinal research

If you want to study the relationship between variables and causal factors responsible for certain outcomes, you should adopt a longitudinal approach to your investigation.

The benefits of longitudinal research over other research methods include the following:

Insights over time

It gives insights into how and why certain things change over time.

Better information

Researchers can better establish sequences of events and identify trends.

No recall bias

The participants won't have recall bias if you use a prospective longitudinal study. Recall bias is an error that occurs in a study if respondents don't wholly or accurately recall the details of their actions, attitudes, or behaviors.

Because variables can change during the study, researchers can discover new relationships or data points worth further investigation.

Small groups

Longitudinal studies don't need a large group of participants.

- Potential pitfalls

The challenges and potential pitfalls of longitudinal studies include the following:

A longitudinal survey takes a long time, involves multiple data collections , and requires complex processes, making it more expensive than other research methods.

Unpredictability

Because they take a long time, longitudinal studies are unpredictable. Unexpected events can cause changes in the variables, making earlier data potentially less valuable.

Slow insights

Researchers can take a long time to uncover insights from the study as it involves multiple observations.

Participants can drop out of the study, limiting the data set and making it harder to draw valid conclusions from the results.

Overly specific data

If you study a smaller group to reduce research costs, results will be less generalizable to larger populations versus a study with a larger group.

Despite these potential pitfalls, you can still derive significant value from a well-designed longitudinal study by uncovering long-term patterns and relationships.

- Longitudinal study designs

Longitudinal studies can take three forms: Repeated cross-sectional, prospective, and retrospective.

Repeated cross-sectional studies

Repeated cross-sectional studies are a type of longitudinal study where participants change across sampling periods. For example, as part of a brand awareness survey , you ask different people from the same customer population about their brand preferences.

Prospective studies

A prospective study is a longitudinal study that involves real-time data collection, and you follow the same participants over a period. Prospective longitudinal studies can be cohort, where participants have similar characteristics or experiences. They can also be panel studies, where you choose the population sample randomly.

Retrospective studies

Retrospective studies are longitudinal studies that involve collecting data on events that some participants have already experienced. Researchers examine historical information to identify patterns that led to an outcome they established at the start of the study. Retrospective studies are the most time and cost-efficient of the three.

- How to perform a longitudinal study

When developing a longitudinal study plan, you must decide whether to collect your data or use data from other sources. Each choice has its benefits and drawbacks.

Using data from other sources

You can freely access data from many previous longitudinal studies, especially studies conducted by governments and research institutes. For example, anyone can access data from the 1970 British Cohort Study on the UK Data Service website .

Using data from other sources saves the time and money you would have spent gathering data. However, the data is more restrictive than the data you collect yourself. You are limited to the variables the original researcher was investigating, and they may have aggregated the data, obscuring some details.

If you can't find data or longitudinal research that applies to your study, the only option is to collect it yourself.

Collecting your own data

Collecting data enhances its relevance, integrity, reliability, and verifiability. Your data collection methods depend on the type of longitudinal study you want to perform. For example, a retrospective longitudinal study collects historical data, while a prospective longitudinal study collects real-time data.

The only way to ensure relevant and reliable data is to use an effective and versatile data collection tool. It can improve the speed and accuracy of the information you collect.

What is a longitudinal study in research?

A longitudinal study is a research design that involves studying the same variables over time by gathering data continuously or repeatedly at consistent intervals.

What is an example of a longitudinal study?

An excellent example of a longitudinal study is market research to identify market trends. The organization's researchers collect data on customers' likes and dislikes to assess market trends and conditions. An organization can also conduct longitudinal studies after launching a new product to understand customers' perceptions and how it is doing in the market.

Why is it called a longitudinal study?

It’s a longitudinal study because you collect data over an extended period. Longitudinal data tracks the same type of information on the same variables at multiple points in time. You collect the data over repeated observations.

What is a longitudinal study vs. a cross-sectional study?

A longitudinal study follows the same people over an extended period, while a cross-sectional study looks at the characteristics of different people or groups at a given time. Longitudinal studies provide insights over an extended period and can establish patterns among variables.

Cross-sectional studies provide insights about a point in time, so they cannot identify cause-and-effect relationships.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

What is a Longitudinal Study?: Definition and Explanation

In this article, we’ll cover all you need to know about longitudinal research.

Let’s take a closer look at the defining characteristics of longitudinal studies, review the pros and cons of this type of research, and share some useful longitudinal study examples.

Content Index

What is a longitudinal study?

Types of longitudinal studies, advantages and disadvantages of conducting longitudinal surveys.

- Longitudinal studies vs. cross-sectional studies

Types of surveys that use a longitudinal study

Longitudinal study examples.

A longitudinal study is a research conducted over an extended period of time. It is mostly used in medical research and other areas like psychology or sociology.

When using this method, a longitudinal survey can pay off with actionable insights when you have the time to engage in a long-term research project.

Longitudinal studies often use surveys to collect data that is either qualitative or quantitative. Additionally, in a longitudinal study, a survey creator does not interfere with survey participants. Instead, the survey creator distributes questionnaires over time to observe changes in participants, behaviors, or attitudes.

Many medical studies are longitudinal; researchers note and collect data from the same subjects over what can be many years.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

Longitudinal studies are versatile, repeatable, and able to account for quantitative and qualitative data . Consider the three major types of longitudinal studies for future research:

Panel study: A panel survey involves a sample of people from a more significant population and is conducted at specified intervals for a more extended period.

One of the panel study’s essential features is that researchers collect data from the same sample at different points in time. Most panel studies are designed for quantitative analysis , though they may also be used to collect qualitative data and unit of analysis .

LEARN ABOUT: Level of Analysis

Cohort Study: A cohort study samples a cohort (a group of people who typically experience the same event at a given point in time). Medical researchers tend to conduct cohort studies. Some might consider clinical trials similar to cohort studies.

In cohort studies, researchers merely observe participants without intervention, unlike clinical trials in which participants undergo tests.

Retrospective study: A retrospective study uses already existing data, collected during previously conducted research with similar methodology and variables.

While doing a retrospective study, the researcher uses an administrative database, pre-existing medical records, or one-to-one interviews.

As we’ve demonstrated, a longitudinal study is useful in science, medicine, and many other fields. There are many reasons why a researcher might want to conduct a longitudinal study. One of the essential reasons is, longitudinal studies give unique insights that many other types of research fail to provide.

Advantages of longitudinal studies

- Greater validation: For a long-term study to be successful, objectives and rules must be established from the beginning. As it is a long-term study, its authenticity is verified in advance, which makes the results have a high level of validity.

- Unique data: Most research studies collect short-term data to determine the cause and effect of what is being investigated. Longitudinal surveys follow the same principles but the data collection period is different. Long-term relationships cannot be discovered in a short-term investigation, but short-term relationships can be monitored in a long-term investigation.

- Allow identifying trends: Whether in medicine, psychology, or sociology, the long-term design of a longitudinal study enables trends and relationships to be found within the data collected in real time. The previous data can be applied to know future results and have great discoveries.

- Longitudinal surveys are flexible: Although a longitudinal study can be created to study a specific data point, the data collected can show unforeseen patterns or relationships that can be significant. Because this is a long-term study, the researchers have a flexibility that is not possible with other research formats.

Additional data points can be collected to study unexpected findings, allowing changes to be made to the survey based on the approach that is detected.

Disadvantages of longitudinal studies

- Research time The main disadvantage of longitudinal surveys is that long-term research is more likely to give unpredictable results. For example, if the same person is not found to update the study, the research cannot be carried out. It may also take several years before the data begins to produce observable patterns or relationships that can be monitored.

- An unpredictability factor is always present It must be taken into account that the initial sample can be lost over time. Because longitudinal studies involve the same subjects over a long period of time, what happens to them outside of data collection times can influence the data that is collected in the future. Some people may decide to stop participating in the research. Others may not be in the correct demographics for research. If these factors are not included in the initial research design, they could affect the findings that are generated.

- Large samples are needed for the investigation to be meaningful To develop relationships or patterns, a large amount of data must be collected and extracted to generate results.

- Higher costs Without a doubt, the longitudinal survey is more complex and expensive. Being a long-term form of research, the costs of the study will span years or decades, compared to other forms of research that can be completed in a smaller fraction of the time.

Longitudinal studies vs. Cross-sectional studies

Longitudinal studies are often confused with cross-sectional studies. Unlike longitudinal studies, where the research variables can change during a study, a cross-sectional study observes a single instance with all variables remaining the same throughout the study. A longitudinal study may follow up on a cross-sectional study to investigate the relationship between the variables more thoroughly.

| Longitudinal studies take a longer time, from years to even a few decades. | Cross-sectional studies are quick to conduct compared to longitudinal studies. |

| A longitudinal study requires an investigator to observe the participants at different time intervals. | A cross-sectional study is conducted over a specified period of time. |

| Longitudinal studies can offer researchers a cause and effect relationship. | Cross-sectional studies cannot offer researchers a cause-and-effect relationship. |

| In longitudinal studies, only one variable can be observed or studied. | With cross-sectional studies, different variables can be observed at a single moment. |

| Longitudinal studies tend to be more expensive. | Cross-sectional studies are more accessible for companies and researchers. |

The design of the study is highly dependent on the nature of the research questions . Whenever a researcher decides to collect data by surveying their participants, what matters most are the questions that are asked in the survey.

Knowing what information a study should gather is the first step in determining how to conduct the rest of the study.

With a longitudinal study, you can measure and compare various business and branding aspects by deploying surveys. Some of the classic examples of surveys that researchers can use for longitudinal studies are:

Market trends and brand awareness: Use a market research survey and marketing survey to identify market trends and develop brand awareness. Through these surveys, businesses or organizations can learn what customers want and what they will discard. This study can be carried over time to assess market trends repeatedly, as they are volatile and tend to change constantly.

Product feedback: If a business or brand launches a new product and wants to know how it is faring with consumers, product feedback surveys are a great option. Collect feedback from customers about the product over an extended time. Once you’ve collected the data, it’s time to put that feedback into practice and improve your offerings.

Customer satisfaction: Customer satisfaction surveys help an organization get to know the level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction among its customers. A longitudinal survey can gain feedback from new and regular customers for as long as you’d like to collect it, so it’s useful whether you’re starting a business or hoping to make some improvements to an established brand.

Employee engagement: When you check in regularly over time with a longitudinal survey, you’ll get a big-picture perspective of your company culture. Find out whether employees feel comfortable collaborating with colleagues and gauge their level of motivation at work.

Now that you know the basics of how researchers use longitudinal studies across several disciplines let’s review the following examples:

Example 1: Identical twins

Consider a study conducted to understand the similarities or differences between identical twins who are brought up together versus identical twins who were not. The study observes several variables, but the constant is that all the participants have identical twins.

In this case, researchers would want to observe these participants from childhood to adulthood, to understand how growing up in different environments influences traits, habits, and personality.

LEARN MORE ABOUT: Personality Survey

Over many years, researchers can see both sets of twins as they experience life without intervention. Because the participants share the same genes, it is assumed that any differences are due to environmental analysis , but only an attentive study can conclude those assumptions.

Example 2: Violence and video games

A group of researchers is studying whether there is a link between violence and video game usage. They collect a large sample of participants for the study. To reduce the amount of interference with their natural habits, these individuals come from a population that already plays video games. The age group is focused on teenagers (13-19 years old).

The researchers record how prone to violence participants in the sample are at the onset. It creates a baseline for later comparisons. Now the researchers will give a log to each participant to keep track of how much and how frequently they play and how much time they spend playing video games. This study can go on for months or years. During this time, the researcher can compare video game-playing behaviors with violent tendencies. Thus, investigating whether there is a link between violence and video games.

Conducting a longitudinal study with surveys is straightforward and applicable to almost any discipline. With our survey software you can easily start your own survey today.

GET STARTED

MORE LIKE THIS

Age Gating: Effective Strategies for Online Content Control

Aug 23, 2024

Customer Experience Lessons from 13,000 Feet — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Aug 20, 2024

Insight: Definition & meaning, types and examples

Aug 19, 2024

Employee Loyalty: Strategies for Long-Term Business Success

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Chapter 7. Longitudinal studies

Clinical follow up studies

- Chapter 1. What is epidemiology?

- Chapter 2. Quantifying disease in populations

- Chapter 3. Comparing disease rates

- Chapter 4. Measurement error and bias

- Chapter 5. Planning and conducting a survey

- Chapter 6. Ecological studies

- Chapter 8. Case-control and cross sectional studies

- Chapter 9. Experimental studies

- Chapter 10. Screening

- Chapter 11. Outbreaks of disease

- Chapter 12. Reading epidemiological reports

- Chapter 13. Further reading

Follow us on

Content links.

- Collections

- Health in South Asia

- Women’s, children’s & adolescents’ health

- News and views

- BMJ Opinion

- Rapid responses

- Editorial staff

- BMJ in the USA

- BMJ in South Asia

- Submit your paper

- BMA members

- Subscribers

- Advertisers and sponsors

Explore BMJ

- Our company

- BMJ Careers

- BMJ Learning

- BMJ Masterclasses

- BMJ Journals

- BMJ Student

- Academic edition of The BMJ

- BMJ Best Practice

- The BMJ Awards

- Email alerts

- Activate subscription

Information

- What’s a Longitudinal Study? Types, Uses & Examples

Research can take anything from a few minutes to years or even decades to complete. When a systematic investigation goes on for an extended period, it’s most likely that the researcher is carrying out a longitudinal study of the sample population. So how does this work?

In the most simple terms, a longitudinal study involves observing the interactions of the different variables in your research population, exposing them to various causal factors, and documenting the effects of this exposure. It’s an intelligent way to establish causal relationships within your sample population.

In this article, we’ll show you several ways to adopt longitudinal studies for your systematic investigation and how to avoid common pitfalls.

What is a Longitudinal Study?

A longitudinal study is a correlational research method that helps discover the relationship between variables in a specific target population. It is pretty similar to a cross-sectional study , although in its case, the researcher observes the variables for a longer time, sometimes lasting many years.

For example, let’s say you are researching social interactions among wild cats. You go ahead to recruit a set of newly-born lion cubs and study how they relate with each other as they grow. Periodically, you collect the same types of data from the group to track their development.

The advantage of this extended observation is that the researcher can witness the sequence of events leading to the changes in the traits of both the target population and the different groups. It can identify the causal factors for these changes and their long-term impact.

Characteristics of Longitudinal Studies