Every child in the United States has a right to a public education, this includes children with Autism and other disabilities. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), is the federal law that guarantees a free and appropriate public education in the least restrictive environment for every student with a disability. The law’s 2004 reauthorization (P.L. 108-446) further defined children’s rights to educational services and strengthened the role of parents/care providers in their children’s educational planning process. This means that the education for students enrolled in public school should come at no cost and should be appropriate for their age, ability, and developmental level.

The law specifies that educational placement should be on an individual basis, not solely on the diagnosis or category of disability.

Parents/care providers have a voice in the educational process. But keep in mind that IDEA requires that an appropriate educational program be provided, but not necessarily the one that is “ideal” for every child. It is important that parents/care providers work with the school to get the educational support and services the student needs.

Educational planning for students with Autism often addresses a wide range of skill development, including academics, communication and language, social skills, self-help skills, behavioral issues, self-advocacy, and leisure-related skills. It’s important to consult with professionals trained specifically in Autism to help a child benefit from their school program. Obtaining a range of opinions is also useful.

- The National Center for Education Statistics maintains a large database of special education demographics.

- The United States Department of Education has dedicated special education statistic resources.

- Approximately 11% of special education students in the United States receive education under the eligibility of Autism.

IEP Information

The Individualized Education Program (IEP) is a written document that outlines a child’s education. As the name implies, the education program should be tailored to the individual student to provide the maximum benefit. The keyword is individual . A program that is appropriate for one child with Autism may not be right for another.

The IEP is the cornerstone for the education of a child with a disability. It should identify the services a child needs so that he/she will meet their learning objectives during the school year. It is also a legal document that outlines:

- The child’s special education plan (goals for the school year)

- Services needed to help the child meet those goals

- A method for evaluating the student’s progress

The objectives, goals, and selected services are not just a collection of ideas on how the school may educate a child; the school district must educate your child in accordance with the IEP.

To develop an IEP, the local education agency officials and others involved in the child’s educational program meet to discuss education-related goals. By law, the following people must be invited to attend the IEP meeting:

- One or both of the child’s parents/care providers

- The child’s teacher or prospective teacher

- A representative of the public agency (local education agency), other than the child’s teacher, who is qualified to provide or supervise the provision of special education

- The child, if appropriate

- Other individuals at the discretion of the parent(s)/care provider(s) or agency (e.g. a physician, advocate, or neighbor)

IEP meetings must be held at least once annually, but may be held more often if needed. Parents/care providers may request a review or revision of the IEP at any time. While teachers and school personnel may come prepared for the meeting with an outline of goals and objectives, the IEP is not complete until it has been thoroughly discussed and all parties agree to the terms of the written document. Parents/care providers are entitled to participate in the IEP meeting as equal participants with suggestions and opinions regarding their child’s education. They may bring a list of suggested goals and objectives as well as additional information that may be pertinent to the IEP meeting.

The local education agency (LEA) must attempt to schedule the IEP meeting at a time and place agreeable to both school staff and parents/care providers. School districts must notify parents/care providers in a timely manner so that they will have an opportunity to attend. The notification must indicate the purpose of the meeting (i.e., to discuss transition services, behavior problems interfering with learning, academic growth).

Learn more about:

- The IEP Meeting

- Related Services

- Teacher/Staff Requirements

- Goals/Objectives/Evaluation

After an evaluation has been done, the IEP meeting will be scheduled. Parents/care providers are entitled by law to attend and participate in this meeting, and must be given ample notification of the time and place. Parents/care providers should also request a copy of the evaluation results prior to the meeting so you have time to review them.

When preparing for your IEP meeting, consider the following:

- What is your vision for your child – for the future as well as the next school year?

- What are your child’s strengths, needs, and interests?

- What are your major concerns about his/her education?

- What has and has not worked in your child’s education thus far?

- Does the evaluation fit with what you know about your child?

- Are there any special factors to consider, such as communication needs or a positive behavioral intervention plan?

While the IEP meeting is meant to develop an education plan for the student, it is also an opportunity for families to share information about their child and their expectations and what techniques have worked at home. If for some reason parents/care providers disagree with the proposed IEP, there is recourse.

Content of the IEP

The IEP should address all areas in which a child needs educational assistance. These can include academic and non-academic goals if the services to be provided will result in educational benefit for the child. All areas of projected need, such as social skills (playing with other children, responding to questions), functional skills (dressing, crossing the street), and related services (occupational, speech, or physical therapy) can also be included in the IEP.

The IEP (see statute text ) should list the setting in which the services will be provided and the professionals who will provide the service. Content of an IEP must include the following:

- A statement of the child’s present level of educational performance. This should include both academic and nonacademic aspects of his/her performance.

- A statement of specific, well-defined goals that the student may reasonably accomplish within the next 12 months. These goals should directly relate to a student’s disability-related needs, and include baseline data supported by the student’s present level of academic and functional performance. It must be clear how goal progress will be monitored and reported

- If your child takes an alternative assessment aligned with alternate achievement standards (ex: Common Core Essential Elements), their IEP goals must include a description of short-term benchmarks or objectives. These objectives help parents/caregivers and educators know whether a student is progressing, or is in need of additional support.

- A description of all specific special education and related services, including individualized instruction and related support and services to be provided (e.g., occupational, physical, and speech therapy; transportation; recreation). This includes the extent to which the child will participate in regular educational programs.

- The initiation date and duration of each of the services, as determined above, to be provided (this can include extended school year services). You may include the person who will be responsible for implementing each service.

- If your child is 16 years of age or older, the IEP must include a description of transition services (a coordinated set of activities to assist the student in movement from school to post-secondary education, employment, or other activities).

Post-Secondary

Transition planning.

Planning for transitions and life after high school is imperative. This is the process that prepares students for adult life after they leave high school. Transition is the bridge between school programming and adult life that might include higher education, employment, independent living, and participation in adult life in the community.

Transition services are mandated under IDEA for children with disabilities ages 16 and up. An Individualized Transition Plan (ITP) is developed for each student. The ITP identifies the desired and expected outcomes for each student and their families once they leave school as well as the support needed to achieve these outcomes.

- The Center on Secondary Education for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders : The Center on Secondary Education for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder (CSESA) is a research and development project funded by the U.S. Department of Education that focuses on developing, adapting, and studying a comprehensive school and community-based education program for high school students who experience Autism.

- The National Technical Assistance Center on Transition : The Collaborative (NTACT:C) is a Technical Assistance Center co-funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) and the Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA).

Info & Resources

Many adults with Autism pursue higher education, earning degrees in their preferred field of study. Many colleges have resources dedicated to supporting students with disabilities such as the student disability service center which may be a component of the college program or additive programs such as the College Internship Program that support students attending colleges and universities. There are also programs available that offer social, academic, career, and life skills support for students who have an intellectual disability that may co-occur with Autism and are not pursuing an academic degree. Information about this type of programming support can be found here .

The experience of attending college or university is a big transition for every student. For students with Autism it may require careful planning to ensure adequate support is in place. Unlike in high school, college and university students must disclose their need for accommodations for instructors and engage in self-advocacy to ensure appropriate accommodations.

Accessing the campus disability support center and inquiring about options for support is an excellent first step. Some of the accommodations that are commonly provided at colleges and universities include: testing accommodations, audio recording of lectures, note-taking services, assistive technologies such as speech to text software, priority class registration, and even housing modifications.

- Each college has a unique culture. Assessing the fit for the individual is important. Size, location, types of support, and academic programming should all be considered. Many adults with Autism report a great college experience, and with a little planning and preparation this can be true for you as well.

- Think College : Think College is a national organization dedicated to developing, expanding, and improving inclusive higher education options for people with intellectual disability.

- College Internship Program : The College Internship Program (CIP) is a private young adult transition program for individuals 18-26 with Autism, ADHD, and other learning differences offering comprehensive and specialized services.

- The Office of Special Education and Rehabilitation Services has an excellent information resource on transition services.

Connect to support from the Autism Society

6110 Executive Boulevard Suite 305 Rockville, Maryland 20852

1 (800) 328-8476 [email protected]

Information

Subscribe to our newsletter, accredited seals.

© 2024 Autism Society

Autism Spectrum Disorder

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) , a component of the National Institutes of Health ( NIH ), is a leading federal funder of research on ASD .

What is autism spectrum disorder?

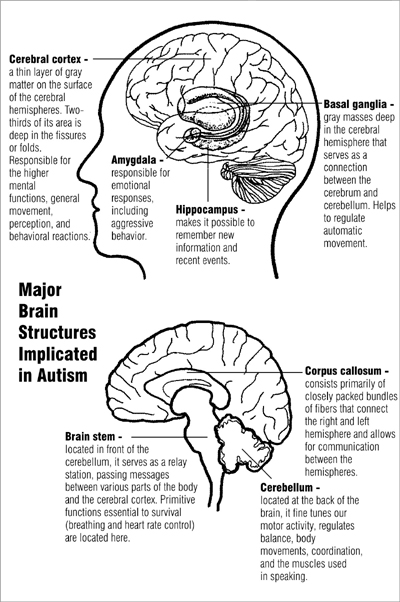

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) refers to a group of complex neurodevelopment disorders caused by differences in the brain that affect communication and behavior. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)—a guide created by the American Psychiatric Association used to diagnose health conditions involving changes in emotion, thinking, or behavior (or a combination of these)—people with ASD can experience:

- Challenges or differences in communication and interaction with other people

- Restricted interests and repetitive behaviors

- Symptoms that may impact the person's ability to function in school, work, and other areas of life

ASD can be diagnosed at any age but symptoms generally appear in early childhood (often within the first two years of life). Doctors diagnose ASD by looking at a person's behavior and development. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that all children get screened for developmental delays and behaviors often associated with ASD at their 18- and 24-month exams.

The term “spectrum” refers to the wide range of symptoms, skills, and levels of ability in functioning that can occur in people with ASD. ASD affects every person differently; some may have only a few symptoms and signs while others have many. Some children and adults with ASD are fully able to perform all activities of daily living and may have gifted learning and cognitive abilities while others require substantial support to perform basic activities. A diagnosis of ASD includes Asperger syndrome, autistic disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified that were once diagnosed as separate disorders.

In addition to differences or challenges with behavior and difficulty communicating and interacting with others, early signs of ASD may include, but are not limited to:

- Avoiding direct eye contact

- Delayed speech and language skills

- Challenges with nonverbal cues such as gestures or body language

- Showing limited interest in other children or caretakers

- Experiencing stress when routines change

Scientists believe that both genetics and environment likely play a role in ASD. ASD occurs in every racial and ethnic group, and across all socioeconomic levels. Males are significantly more likely to develop ASD than females.

People with ASD also have an increased risk of having epilepsy. Children whose language skills regress early in life—before age 3—appear to have a risk of developing epilepsy or seizure-like brain activity. About 20 to 30 percent of children with ASD develop epilepsy by the time they reach adulthood.

Currently, there is no cure for ASD. Symptoms of ASD can last through a person's lifetime, and some may improve with age, treatment, and services. Therapies and educational/behavioral interventions are designed to remedy specific symptoms and can substantially improve those symptoms. While currently approved medications cannot cure ASD or even treat its main symptoms, there are some that can help with related symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Medications are available to treat seizures, severe behavioral problems, and impulsivity and hyperactivity.

How can I or my loved one help improve care for people with autism spectrum disorder?

Consider participating in a clinical trial so clinicians and scientists can learn more about ASD and related conditions. Clinical trials are studies that use human volunteers to look for new or better ways to diagnose, treat, or cure diseases and conditions.

All types of volunteers are needed—people with ASD, at-risk individuals, and healthy volunteers—of all different ages, sexes, races, and ethnicities to ensure that study results apply to as many people as possible, and that treatments will be safe and effective for everyone who will use them.

For information about participating in clinical research visit NIH Clinical Research Trials and You . Learn about clinical trials currently looking for people with ASD at Clinicaltrials.gov .

Where can I find more information about autism spectrum disorder? The following resources offer information about ASD and current research: American Academy of Pediatrics Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences The National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices (NTG) Additional organizations offer information, research news, and other resources about ASD for individuals and caregivers, such as support groups. These organizations include: Association for Science in Autism Treatment Autism National Committee (AUTCOM) Autism Network International (ANI) Autism Research Institute (ARI) Autism Science Foundation Autism Society Autism Speaks, Inc.

- Copy/Paste Link Link Copied

Educational and School-Based Therapies for Autism

Children with autism are guaranteed free, appropriate public education under the federal laws of Public Law 108-177: Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (2004) , sometimes called "IDEA."

IDEA ensures that children diagnosed with certain disabilities or conditions, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), get free educational services and educational devices to help them to learn as much as they can.

NICHD-funded researchers have also incorporated communications interventions for children with ASD within the classroom setting, with successful outcomes. Although the specific interventions used in the study are not a guaranteed part of IDEA, components from the program could provide an important evidence-based foundation for future school-based therapies. 1

IDEA Covers Children and Young Adults

Educational Environment

IDEA states that children must be taught in the "least restrictive environment, appropriate for that individual child." This means the teaching environment should:

- Be designed to meet a child's specific needs and skills

- Minimize restrictions on the child's access to typical learning experiences and interactions

Educating people with autism often includes a combination of one-on-one, small group, and regular classroom instruction.

Individualized Education Program (IEP)

The special education team in your child's school will work with you to design an IEP (also called an individualized education plan) for your child. 2 An IEP is a written document that:

- Lists individualized goals for your child

- Specifies the plan for services your child will receive

- Lists the developmental specialists who will work with your child

Qualifying for Special Education

To qualify for access to special education services, the child must be evaluated by the school system and meet specific criteria as outlined by federal and state guidelines. To learn how to have your child assessed for special services, you can:

- Contact a local school principal or special education coordinator

Consult a parents' organization to get information on therapeutic and educational services and how to get these services for a child. Visit the Resources and Publications: For Patients and Consumers section for a list of these organizations.

- Chang, Y. C., Shire, S. Y., Shih, W., Gelfand, C., & Kasari, C. (2016). Preschool deployment of evidence-based social communication intervention: JASPER in the classroom. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46 (6), 2211–2223. Retrieved September 8, 2016, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26936161

Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- HIV and AIDS

- Hypertension

- Mental disorders

- Top 10 causes of death

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- Data collection tools

- Global Health Observatory

- Insights and visualizations

- COVID excess deaths

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Fact sheets /

- Autism – also referred to as autism spectrum disorder ̶ constitutes a diverse group of conditions related to development of the brain.

- About 1 in 100 children has autism.

- Characteristics may be detected in early childhood, but autism is often not diagnosed until much later.

- The abilities and needs of autistic people vary and can evolve over time. While some people with autism can live independently, others have severe disabilities and require life-long care and support.

- Evidence-based psychosocial interventions can improve communication and social skills, with a positive impact on the well-being and quality of life of both autistic people and their caregivers.

- Care for people with autism needs to be accompanied by actions at community and societal levels for greater accessibility, inclusivity and support.

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are a diverse group of conditions. They are characterized by some degree of difficulty with social interaction and communication. Other characteristics are atypical patterns of activities and behaviours, such as difficulty with transition from one activity to another, a focus on details and unusual reactions to sensations.

The abilities and needs of autistic people vary and can evolve over time. While some people with autism can live independently, others have severe disabilities and require life-long care and support. Autism often has an impact on education and employment opportunities. In addition, the demands on families providing care and support can be significant. Societal attitudes and the level of support provided by local and national authorities are important factors determining the quality of life of people with autism.

Characteristics of autism may be detected in early childhood, but autism is often not diagnosed until much later.

People with autism often have co-occurring conditions, including epilepsy, depression, anxiety and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as well as challenging behaviours such as difficulty sleeping and self-injury. The level of intellectual functioning among autistic people varies widely, extending from profound impairment to superior levels.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that worldwide about 1 in 100 children has autism (1) . This estimate represents an average figure, and reported prevalence varies substantially across studies. Some well-controlled studies have, however, reported figures that are substantially higher. The prevalence of autism in many low- and middle-income countries is unknown.

Available scientific evidence suggests that there are probably many factors that make a child more likely to have autism, including environmental and genetic factors.

Extensive research using a variety of different methods and conducted over many years has demonstrated that the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine does not cause autism. Studies that were interpreted as indicating any such link were flawed, and some of the authors had undeclared biases that influenced what they reported about their research (2,3,4) .

Evidence also shows that other childhood vaccines do not increase the risk of autism. Extensive research into the preservative thiomersal and the additive aluminium that are contained in some inactivated vaccines strongly concluded that these constituents in childhood vaccines do not increase the risk of autism.

Assessment and care

A broad range of interventions, from early childhood and across the life span, can optimize the development, health, well-being and quality of life of autistic people. Timely access to early evidence-based psychosocial interventions can improve the ability of autistic children to communicate effectively and interact socially. The monitoring of child development as part of routine maternal and child health care is recommended.

It is important that, once autism has been diagnosed, children, adolescents and adults with autism and their carers are offered relevant information, services, referrals, and practical support, in accordance with their individual and evolving needs and preferences.

The health-care needs of people with autism are complex and require a range of integrated services, that include health promotion, care and rehabilitation. Collaboration between the health sector and other sectors, particularly education, employment and social care, is important.

Interventions for people with autism and other developmental disabilities need to be designed and delivered with the participation of people living with these conditions. Care needs to be accompanied by actions at community and societal levels for greater accessibility, inclusivity and support.

Human rights

All people, including people with autism, have the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.

And yet, autistic people are often subject to stigma and discrimination, including unjust deprivation of health care, education and opportunities to engage and participate in their communities.

People with autism have the same health problems as the general population. However, they may, in addition, have specific health-care needs related to autism or other co-occurring conditions. They may be more vulnerable to developing chronic noncommunicable conditions because of behavioural risk factors such as physical inactivity and poor dietary preferences, and are at greater risk of violence, injury and abuse.

People with autism require accessible health services for general health-care needs like the rest of the population, including promotive and preventive services and treatment of acute and chronic illness. Nevertheless, autistic people have higher rates of unmet health-care needs compared with the general population. They are also more vulnerable during humanitarian emergencies. A common barrier is created by health-care providers’ inadequate knowledge and understanding of autism.

WHO resolution on autism spectrum disorders

In May 2014, the Sixty-seventh World Health Assembly adopted a resolution entitled Comprehensive and coordinated efforts for the management of autism spectrum disorders , which was supported by more than 60 countries.

The resolution urges WHO to collaborate with Member States and partner agencies to strengthen national capacities to address ASD and other developmental disabilities.

WHO response

WHO and partners recognize the need to strengthen countries' abilities to promote the optimal health and well-being of all people with autism. WHO's efforts focus on:

- increasing the commitment of governments to taking action to improve the quality of life of people with autism;

- providing guidance on policies and action plans that address autism within the broader framework of health, mental and brain health and disabilities;

- contributing to strengthening the ability of the health workforce to provide appropriate and effective care and promote optimal standards of health and well-being for people with autism; and

- promoting inclusive and enabling environments for people with autism and other developmental disabilities and providing support to their caregivers.

WHO Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2030 and World Health Assembly Resolution WHA73.10 for “global actions on epilepsy and other neurological disorders” calls on countries to address the current significant gaps in early detection, care, treatment and rehabilitation for mental and neurodevelopmental conditions, which include autism. It also calls for counties to address the social, economic, educational and inclusion needs of people living with mental and neurological disorders, and their families, and to improve surveillance and relevant research.

1 . Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Zeidan J et al. Autism Research 2022 March.

2. Wakefield's affair: 12 years of uncertainty whereas no link between autism and MMR vaccine has been proved. Maisonneuve H, Floret D. Presse Med. 2012 Sep; French ( https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22748860 ).

3. Lancet retracts Wakefield’s MMR paper. Dyer C. BMJ 2010;340:c696. 2 February 2010 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20124366/)

4. Kmietowicz Z. Wakefield is struck off for the “serious and wide-ranging findings against him” BMJ 2010; 340 :c2803 doi:10.1136/bmj.c2803 ( https://www.bmj.com/content/340/bmj.c2803 )

Training for caregivers of children with development delays and disabilities

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Dev Disabil

- v.64(2); 2018

Autism spectrum disorders: identification, education, and treatment

Leslie ann bross.

a University of Kansas

Autism spectrum disorders: identification, education, and treatment , 4th edition, edited by ZagerDianne, CihakDavid F., and Stone-MacDonaldAngi, editors. . New York: Routledge; 2017. ISBN 978-1-138-01569-2

The fourth edition of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Identification, Education, and Treatment provides current and prospective professionals and researchers with a timely update of issues relevant to the field of autism. This new edition describes up-to-date trends and issues critical for the treatment of children, adolescents, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Many of the contributing authors are well recognized and emergent leaders within the field with expertise and knowledge about meeting the complex needs of learners with ASD. The book is organized into three sections. The first section is an overview of the field including changes in diagnostic criteria. The second section is comprised of chapters focused on evidence-based practices for infants up to the elementary/primary school years. The final section focuses on the needs of adolescents and young adults with autism, with specific attention to self-determination and universal design for learning. Readers will likely find this organization useful for finding information specific to their professional and research needs.

The first five chapters provide a thorough historical perspective of the field. The revised clinical diagnostic criteria published in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th edition (American Psychological Association, 2013) are described in detail. Updates on assessment tools for accurate diagnosis are helpful to the reader. An overview of legislation and litigation issues related to individuals with ASD describes relevant law and example court cases. In addition, a summary of possible service delivery models is provided with substantial practical details for professionals. The global perspective chapter is a particularly welcomed addition from previous editions because of the overview of autism treatments described around the world.

Middle chapters provide descriptions of evidence-based practices to inform readers what intervention programs should include for children with autism from birth to elementary/primary school years. Specific interventions are described with applicable examples supported by current empirical research. The chapter on communication and language development includes the most current research on language and communication programming, including augmentative and alternative communication systems such as picture exchange communication system, speech generating devices and functional communication training. Professionals will find this content especially useful given that communication programming tends to be a very high priority for intervention programming. The chapter on managing appropriate behaviors provides a valuable overview of data collection procedures and behavior interventions grounded in principles of behavior consistent with applied behavior analysis. A new chapter on academic skills interventions rounds this section along with a chapter on social interaction competence.

The final section of the text includes chapters focused on transition to adulthood for adolescents and young adults with ASD. The importance of self-determination, student involvement in transition planning, and the recently proposed framework called universal design for transition is discussed in detail. Interdisciplinary collaboration is also a focus, along with current research and practice related to positive behavior supports and integrated employment. Professionals working with middle and high school students with ASD will particularly benefit from the overview of evidence-based practices in transition planning to address the persistently poor postsecondary outcomes of individuals with ASD.

Overall, the book will prove an excellent resource for professionals charged with daily service and support of learners with ASD, and psychiatric and other related medical professionals will find it a useful reference for their personal library. Researchers and teacher educators also will find this revision replete with current knowledge and evidence regarding demonstrably effective interventions. It is a highly recommended resource for any professional who will provide services to learners with autism.

NASET.org Home Page

Exceptional teachers teaching exceptional children.

- Overview of NASET

- NASET Leadership

- Directors' Message

- Books by the Executive Directors

- Mission Statement

- NASET Apps for iPhone and iPad

- NASET Store

- NASET Sponsors

- Marketing Opportunities

- Contact NASET

- Renew Your Membership

- Membership Benefits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Membership Categories

- School / District Membership Information

- Gift Membership

- Membership Benefit for Professors Only

- NASET's Privacy Policy

- Forgot Your User Name or Password?

- Contact Membership Department

- Resources for Special Education Teachers

- Advocacy (Board Certification for Advocacy in Special Education) BCASE

- Board Certification in Special Education

- Inclusion - Board Certification in Inclusion in Special Education (BCISE) Program

- Paraprofessional Skills Preparation Program - PSPP

- Professional Development Program (PDP) Free to NASET Members

- Courses - Professional Development Courses (Free With Membership)

- Forms, Tables, Checklists, and Procedures for Special Education Teachers

- Video and Power Point Library

- IEP Development

- Exceptional Students and Disability Information

- Special Education and the Law

- Transition Services

- Literacy - Teaching Literacy in English to K-5 English Learners

- Facebook - Special Education Teacher Group

- NASET Sponsor's Products and Services

- ADHD Series

- Assessment in Special Education Series

- Autism Spectrum Disorders Series

- Back to School - Special Review

- Bullying of Children

- Classroom Management Series

- Diagnosis of Students with Disabilities and Disorders Series

- Treatment of Disabilities and Disorders for Students Receiving Special Education and Related Services

- Discipline of Students in Special Education Series

- Early Intervention Series

- Genetics in Special Education Series

- How To Series

- Inclusion Series

- IEP Components

- JAASEP - Research Based Journal in Special Education

- Lesser Known Disorders

- NASET NEWS ALERTS

- NASET Q & A Corner

- Parent Teacher Conference Handouts

- The Practical Teacher

- Resolving Disputes with Parents Series

- RTI Roundtable

- Severe Disabilities Series

- Special Educator e-Journal - Latest and Archived Issues

- Week in Review

- Working with Paraprofessionals in Your School

- Author Guidelines for Submission of Manuscripts & Articles to NASET

- SCHOOLS of EXCELLENCE

- Exceptional Charter School in Special Education

- Outstanding Special Education Teacher Award

- Board Certification Programs

- Employers - Job Posting Information

- Latest Job Listings

- Professional Development Program (PDP)

- Employers-Post a Job on NASET

- PDP - Professional Development Courses

- Board Certification in Special Education (BCSE)

- Board Certification in IEP Development (BCIEP)

- NASET Continuing Education/Professional Development Courses

- HONOR SOCIETY - Omega Gamma Chi

- Other Resources for Special Education Teaching Positions

- Highly Qualified Teachers

- Special Education Career Advice

- Special Education Career Fact Sheets

- FAQs for Special Education Teachers

- Special Education Teacher Salaries by State

- State Licensure for Special Education Teachers

Autism Spectrum Disorders

Autism spectrum disorders (pervasive developmental disorders).

Not until the middle of the twentieth century was there a name for a disorder that now appears to affect an estimated one of every five hundred children, a disorder that causes disruption in families and unfulfilled lives for many children. In 1943 Dr. Leo Kanner of the Johns Hopkins Hospital studied a group of 11 children and introduced the label early infantile autism into the English language. At the same time a German scientist, Dr. Hans Asperger, described a milder form of the disorder that became known as Asperger syndrome. Thus these two disorders were described and are today listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV-TR (fourth edition, text revision) 1 as two of the five pervasive developmental disorders (PDD), more often referred to today as autism spectrum disorders (ASD). All these disorders are characterized by varying degrees of impairment in communication skills, social interactions, and restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior.

The autism spectrum disorders can often be reliably detected by the age of 3 years, and in some cases as early as 18 months. 2 Studies suggest that many children eventually may be accurately identified by the age of 1 year or even younger. The appearance of any of the warning signs of ASD is reason to have a child evaluated by a professional specializing in these disorders.

Parents are usually the first to notice unusual behaviors in their child. In some cases, the baby seemed "different" from birth, unresponsive to people or focusing intently on one item for long periods of time. The first signs of an ASD can also appear in children who seem to have been developing normally. When an engaging, babbling toddler suddenly becomes silent, withdrawn, self-abusive, or indifferent to social overtures, something is wrong. Research has shown that parents are usually correct about noticing developmental problems, although they may not realize the specific nature or degree of the problem.

The pervasive developmental disorders, or autism spectrum disorders, range from a severe form, called autistic disorder, to a milder form, Asperger syndrome. If a child has symptoms of either of these disorders, but does not meet the specific criteria for either, the diagnosis is called pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS). Other rare, very severe disorders that are included in the autism spectrum disorders are Rett syndrome and childhood disintegrative disorder. This brochure will focus on classic autism, PDD-NOS, and Asperger syndrome, with brief descriptions of Rett syndrome and childhood disintegrative disorder on the following page.

Rare Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Rett Syndrome

Rett syndrome is relatively rare, affecting almost exclusively females, one out of 10,000 to 15,000. After a period of normal development, sometime between 6 and 18 months, autism-like symptoms begin to appear. The little girl's mental and social development regresses—she no longer responds to her parents and pulls away from any social contact. If she has been talking, she stops; she cannot control her feet; she wrings her hands. Some of the problems associated with Rett syndrome can be treated. Physical, occupational, and speech therapy can help with problems of coordination, movement, and speech. Scientists sponsored by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development have discovered that a mutation in the sequence of a single gene can cause Rett syndrome. This discovery may help doctors slow or stop the progress of the syndrome. It may also lead to methods of screening for Rett syndrome, thus enabling doctors to start treating these children much sooner, and improving the quality of life these children experience. *

Childhood Disintegrative Disorder

Very few children who have an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis meet the criteria for childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD). An estimate based on four surveys of ASD found fewer than two children per 100,000 with ASD could be classified as having CDD. This suggests that CDD is a very rare form of ASD. It has a strong male preponderance. ** Symptoms may appear by age 2, but the average age of onset is between 3 and 4 years. Until this time, the child has age-appropriate skills in communication and social relationships. The long period of normal development before regression helps differentiate CDD from Rett syndrome.

The loss of such skills as vocabulary are more dramatic in CDD than they are in classical autism. The diagnosis requires extensive and pronounced losses involving motor, language, and social skills. *** CDD is also accompanied by loss of bowel and bladder control and oftentimes seizures and a very low IQ. *Rett syndrome. NIH Publication No. 01-4960. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2001. Available at http://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/pubskey.cfm?from=autism

**Frombonne E. Prevalence of childhood disintegrative disorder. Autism, 2002; 6(2): 149-157. ***Volkmar RM and Rutter M. Childhood disintegrative disorder: Results of the DSM-IV autism field trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1995; 34: 1092-1095.

What Are the Autism Spectrum Disorders?

The autism spectrum disorders are more common in the pediatric population than are some better known disorders such as diabetes, spinal bifida, or Down syndrome. 2 Prevalence studies have been done in several states and also in the United Kingdom, Europe, and Asia. Prevalence estimates range from 2 to 6 per 1,000 children. This wide range of prevalence points to a need for earlier and more accurate screening for the symptoms of ASD. The earlier the disorder is diagnosed, the sooner the child can be helped through treatment interventions. Pediatricians, family physicians, daycare providers, professionals, and parents may initially dismiss signs of ASD, optimistically thinking the child is just a little slow and will "catch up." Although early intervention has a dramatic impact on reducing symptoms and increasing a child's ability to grow and learn new skills, it is estimated that only 50 percent of children are diagnosed before kindergarten .

All children with ASD demonstrate deficits in 1) social interaction, 2) verbal and nonverbal communication, and 3) repetitive behaviors or interests. In addition, they will often have unusual responses to sensory experiences, such as certain sounds or the way objects look. Each of these symptoms runs the gamut from mild to severe. They will present in each individual child differently. For instance, a child may have little trouble learning to read but exhibit extremely poor social interaction. Each child will display communication, social, and behavioral patterns that are individual but fit into the overall diagnosis of ASD.

Children with ASD do not follow the typical patterns of child development. In some children, hints of future problems may be apparent from birth. In most cases, the problems in communication and social skills become more noticeable as the child lags further behind other children the same age. Some other children start off well enough. Oftentimes between 12 and 36 months old, the differences in the way they react to people and other unusual behaviors become apparent. Some parents report the change as being sudden, and that their children start to reject people, act strangely, and lose language and social skills they had previously acquired. In other cases, there is a plateau, or leveling, of progress so that the difference between the child with autism and other children the same age becomes more noticeable.

ASD is defined by a certain set of behaviors that can range from the very mild to the severe. The following possible indicators of ASD were identified on the Public Health Training Network Webcast, Autism Among Us. 3

Possible Indicators of Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Does not babble, point, or make meaningful gestures by 1 year of age

- Does not speak one word by 16 months

- Does not combine two words by 2 years

- Does not respond to name

- Loses language or social skills

Some Other Indicators

- Poor eye contact

- Doesn't seem to know how to play with toys

- Excessively lines up toys or other objects

- Is attached to one particular toy or object

- Doesn't smile

- At times seems to be hearing impaired

Social Symptoms

From the start, typically developing infants are social beings. Early in life, they gaze at people, turn toward voices, grasp a finger, and even smile.

In contrast, most children with ASD seem to have tremendous difficulty learning to engage in the give-and-take of everyday human interaction. Even in the first few months of life, many do not interact and they avoid eye contact. They seem indifferent to other people, and often seem to prefer being alone. They may resist attention or passively accept hugs and cuddling. Later, they seldom seek comfort or respond to parents' displays of anger or affection in a typical way. Research has suggested that although children with ASD are attached to their parents, their expression of this attachment is unusual and difficult to "read." To parents, it may seem as if their child is not attached at all. Parents who looked forward to the joys of cuddling, teaching, and playing with their child may feel crushed by this lack of the expected and typical attachment behavior.

Children with ASD also are slower in learning to interpret what others are thinking and feeling. Subtle social cues—whether a smile, a wink, or a grimace—may have little meaning. To a child who misses these cues, "Come here" always means the same thing, whether the speaker is smiling and extending her arms for a hug or frowning and planting her fists on her hips. Without the ability to interpret gestures and facial expressions, the social world may seem bewildering. To compound the problem, people with ASD have difficulty seeing things from another person's perspective. Most 5-year-olds understand that other people have different information, feelings, and goals than they have. A person with ASD may lack such understanding. This inability leaves them unable to predict or understand other people's actions.

Although not universal, it is common for people with ASD also to have difficulty regulating their emotions. This can take the form of "immature" behavior such as crying in class or verbal outbursts that seem inappropriate to those around them. The individual with ASD might also be disruptive and physically aggressive at times, making social relationships still more difficult. They have a tendency to "lose control," particularly when they're in a strange or overwhelming environment, or when angry and frustrated. They may at times break things, attack others, or hurt themselves. In their frustration, some bang their heads, pull their hair, or bite their arms.

Communication Difficulties

By age 3, most children have passed predictable milestones on the path to learning language; one of the earliest is babbling. By the first birthday, a typical toddler says words, turns when he hears his name, points when he wants a toy, and when offered something distasteful, makes it clear that the answer is "no." Some children diagnosed with ASD remain mute throughout their lives. Some infants who later show signs of ASD coo and babble during the first few months of life, but they soon stop. Others may be delayed, developing language as late as age 5 to 9. Some children may learn to use communication systems such as pictures or sign language. Those who do speak often use language in unusual ways. They seem unable to combine words into meaningful sentences. Some speak only single words, while others repeat the same phrase over and over. Some ASD children parrot what they hear, a condition called echolalia . Although many children with no ASD go through a stage where they repeat what they hear, it normally passes by the time they are 3. Some children only mildly affected may exhibit slight delays in language, or even seem to have precocious language and unusually large vocabularies, but have great difficulty in sustaining a conversation. The "give and take" of normal conversation is hard for them, although they often carry on a monologue on a favorite subject, giving no one else an opportunity to comment. Another difficulty is often the inability to understand body language, tone of voice, or "phrases of speech." They might interpret a sarcastic expression such as "Oh, that's just great" as meaning it really IS great. While it can be hard to understand what ASD children are saying, their body language is also difficult to understand. Facial expressions, movements, and gestures rarely match what they are saying. Also, their tone of voice fails to reflect their feelings. A high-pitched, sing-song, or flat, robot-like voice is common. Some children with relatively good language skills speak like little adults, failing to pick up on the "kid-speak" that is common in their peers. Without meaningful gestures or the language to ask for things, people with ASD are at a loss to let others know what they need. As a result, they may simply scream or grab what they want. Until they are taught better ways to express their needs, ASD children do whatever they can to get through to others. As people with ASD grow up, they can become increasingly aware of their difficulties in understanding others and in being understood. As a result they may become anxious or depressed.

Repetitive Behaviors

Although children with ASD usually appear physically normal and have good muscle control, odd repetitive motions may set them off from other children. These behaviors might be extreme and highly apparent or more subtle. Some children and older individuals spend a lot of time repeatedly flapping their arms or walking on their toes. Some suddenly freeze in position.

As children, they might spend hours lining up their cars and trains in a certain way, rather than using them for pretend play. If someone accidentally moves one of the toys, the child may be tremendously upset. ASD children need, and demand, absolute consistency in their environment. A slight change in any routine—in mealtimes, dressing, taking a bath, going to school at a certain time and by the same route—can be extremely disturbing. Perhaps order and sameness lend some stability in a world of confusion.

Repetitive behavior sometimes takes the form of a persistent, intense preoccupation. For example, the child might be obsessed with learning all about vacuum cleaners, train schedules, or lighthouses. Often there is great interest in numbers, symbols, or science topics.

Problems That May Accompany ASD

Sensory problems. When children's perceptions are accurate, they can learn from what they see, feel, or hear. On the other hand, if sensory information is faulty, the child's experiences of the world can be confusing. Many ASD children are highly attuned or even painfully sensitive to certain sounds, textures, tastes, and smells. Some children find the feel of clothes touching their skin almost unbearable. Some sounds—a vacuum cleaner, a ringing telephone, a sudden storm, even the sound of waves lapping the shoreline—will cause these children to cover their ears and scream. In ASD, the brain seems unable to balance the senses appropriately. Some ASD children are oblivious to extreme cold or pain. An ASD child may fall and break an arm, yet never cry. Another may bash his head against a wall and not wince, but a light touch may make the child scream with alarm.

Intellectual Disability. Many children with ASD have some degree of mental impairment. When tested, some areas of ability may be normal, while others may be especially weak. For example, a child with ASD may do well on the parts of the test that measure visual skills but earn low scores on the language subtests.

Seizures. One in four children with ASD develops seizures, often starting either in early childhood or adolescence. 4 Seizures, caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain, can produce a temporary loss of consciousness (a "blackout"), a body convulsion, unusual movements, or staring spells. Sometimes a contributing factor is a lack of sleep or a high fever. An EEG (electroencephalogram—recording of the electric currents developed in the brain by means of electrodes applied to the scalp) can help confirm the seizure's presence. In most cases, seizures can be controlled by a number of medicines called "anticonvulsants." The dosage of the medication is adjusted carefully so that the least possible amount of medication will be used to be effective.

Fragile X syndrome. This disorder is the most common inherited form of mental retardation. It was so named because one part of the X chromosome has a defective piece that appears pinched and fragile when under a microscope. Fragile X syndrome affects about two to five percent of people with ASD. It is important to have a child with ASD checked for Fragile X, especially if the parents are considering having another child. For an unknown reason, if a child with ASD also has Fragile X, there is a one-in-two chance that boys born to the same parents will have the syndrome. 5 Other members of the family who may be contemplating having a child may also wish to be checked for the syndrome.

Tuberous Sclerosis. Tuberous sclerosis is a rare genetic disorder that causes benign tumors to grow in the brain as well as in other vital organs. It has a consistently strong association with ASD. One to 4 percent of people with ASD also have tuberous sclerosis. 6

The Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorders

Although there are many concerns about labeling a young child with an ASD, the earlier the diagnosis of ASD is made, the earlier needed interventions can begin. Evidence over the last 15 years indicates that intensive early intervention in optimal educational settings for at least 2 years during the preschool years results in improved outcomes in most young children with ASD. 2 In evaluating a child, clinicians rely on behavioral characteristics to make a diagnosis. Some of the characteristic behaviors of ASD may be apparent in the first few months of a child's life, or they may appear at any time during the early years. For the diagnosis, problems in at least one of the areas of communication, socialization, or restricted behavior must be present before the age of 3. The diagnosis requires a two-stage process. The first stage involves developmental screening during "well child" check-ups; the second stage entails a comprehensive evaluation by a multidisciplinary team. 7 ;

A "well child" check-up should include a developmental screening test. If your child's pediatrician does not routinely check your child with such a test, ask that it be done. Your own observations and concerns about your child's development will be essential in helping to screen your child.7 Reviewing family videotapes, photos, and baby albums can help parents remember when each behavior was first noticed and when the child reached certain developmental milestones. Several screening instruments have been developed to quickly gather information about a child's social and communicative development within medical settings. Among them are the Checklist of Autism in Toddlers (CHAT),8 the modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT),9 the Screening Tool for Autism in Two-Year-Olds (STAT),10 and the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ)11 (for children 4 years of age and older). Some screening instruments rely solely on parent responses to a questionnaire, and some rely on a combination of parent report and observation. Key items on these instruments that appear to differentiate children with autism from other groups before the age of 2 include pointing and pretend play. Screening instruments do not provide individual diagnosis but serve to assess the need for referral for possible diagnosis of ASD. These screening methods may not identify children with mild ASD, such as those with high-functioning autism or Asperger syndrome. During the last few years, screening instruments have been devised to screen for Asperger syndrome and higher functioning autism. The Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ),12 the Australian Scale for Asperger's Syndrome,13 and the most recent, the Childhood Asperger Syndrome Test (CAST),14 are some of the instruments that are reliable for identification of school-age children with Asperger syndrome or higher functioning autism. These tools concentrate on social and behavioral impairments in children without significant language delay. If, following the screening process or during a routine "well child" check-up, your child's doctor sees any of the possible indicators of ASD, further evaluation is indicated.

Comprehensive Diagnostic Evaluation The second stage of diagnosis must be comprehensive in order to accurately rule in or rule out an ASD or other developmental problem. This evaluation may be done by a multidisciplinary team that includes a psychologist, a neurologist, a psychiatrist, a speech therapist, or other professionals who diagnose children with ASD. Because ASDs are complex disorders and may involve other neurological or genetic problems, a comprehensive evaluation should entail neurologic and genetic assessment, along with in-depth cognitive and language testing. 7 In addition, measures developed specifically for diagnosing autism are often used. These include the Autism Diagnosis Interview-Revised (ADI-R) 15 and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-G). 16 The ADI-R is a structured interview that contains over 100 items and is conducted with a caregiver. It consists of four main factors—the child's communication, social interaction, repetitive behaviors, and age-of-onset symptoms. The ADOS-G is an observational measure used to "press" for socio-communicative behaviors that are often delayed, abnormal, or absent in children with ASD. Still another instrument often used by professionals is the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). 17 It aids in evaluating the child's body movements, adaptation to change, listening response, verbal communication, and relationship to people. It is suitable for use with children over 2 years of age. The examiner observes the child and also obtains relevant information from the parents. The child's behavior is rated on a scale based on deviation from the typical behavior of children of the same age. Two other tests that should be used to assess any child with a developmental delay are a formal audiologic hearing evaluation and a lead screening. Although some hearing loss can co-occur with ASD, some children with ASD may be incorrectly thought to have such a loss. In addition, if the child has suffered from an ear infection, transient hearing loss can occur. Lead screening is essential for children who remain for a long period of time in the oral-motor stage in which they put any and everything into their mouths. Children with an autistic disorder usually have elevated blood lead levels. 7

Available Aids

When your child has been evaluated and diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder, you may feel inadequate to help your child develop to the fullest extent of his or her ability. As you begin to look at treatment options and at the types of aid available for a child with a disability, you will find out that there is help for you. It is going to be difficult to learn and remember everything you need to know about the resources that will be most helpful. Write down everything. If you keep a notebook, you will have a foolproof method of recalling information. Keep a record of the doctors' reports and the evaluation your child has been given so that his or her eligibility for special programs will be documented. Learn everything you can about special programs for your child; the more you know, the more effectively you can advocate. For every child eligible for special programs, each state guarantees special education and related services. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is a Federally mandated program that assures a free and appropriate public education for children with diagnosed learning deficits. Usually children are placed in public schools and the school district pays for all necessary services. These will include, as needed, services by a speech therapist, occupational therapist, school psychologist, social worker, school nurse, or aide. By law, the public schools must prepare and carry out a set of instruction goals, or specific skills, for every child in a special education program. The list of skills is known as the child's Individualized Education Program (IEP). The IEP is an agreement between the school and the family on the child's goals. When your child's IEP is developed, you will be asked to attend the meeting. There will be several people at this meeting, including a special education professional, a representative of the public schools who is knowledgeable about the program, other individuals invited by the school or by you (you may want to bring a relative, a child care provider, or a supportive close friend who knows your child well). Parents play an important part in creating the program, as they know their child and his or her needs best. Once your child's IEP is developed, a meeting is scheduled once a year to review your child's progress and to make any alterations to reflect his or her changing needs. If your child is under 3 years of age and has special needs, he or she should be eligible for an early intervention program; this program is available in every state. Each state decides which agency will be the lead agency in the early intervention program. The early intervention services are provided by workers qualified to care for toddlers with disabilities and are usually in the child's home or a place familiar to the child. The services provided are written into an Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) that is reviewed at least once every 6 months. The plan will describe services that will be provided to the child, but will also describe services for parents to help them in daily activities with their child and for siblings to help them adjust to having a brother or sister with ASD. There is a list of resources at the back of the brochure that will be helpful to you as you look for programs for your child.

Treatment Options

There is no single best treatment package for all children with ASD. One point that most professionals agree on is that early intervention is important; another is that most individuals with ASD respond well to highly structured, specialized programs. Before you make decisions on your child's treatment, you will want to gather information about the various options available. Learn as much as you can, look at all the options, and make your decision on your child's treatment based on your child's needs. You may want to visit public schools in your area to see the type of program they offer to special needs children. Guidelines used by the Autism Society of America include the following questions parents can ask about potential treatments:

- Will the treatment result in harm to my child?

- How will failure of the treatment affect my child and family?

- Has the treatment been validated scientifically?

- Are there assessment procedures specified?

- How will the treatment be integrated into my child's current program?

Do not become so infatuated with a given treatment that functional curriculum, vocational life, and social skills are ignored.

The National Institute of Mental Health suggests a list of questions parents can ask when planning for their child:

- How successful has the program been for other children?

- How many children have gone on to placement in a regular school and how have they performed?

- Do staff members have training and experience in working with children and adolescents with autism?

- How are activities planned and organized?

- Are there predictable daily schedules and routines?

- How much individual attention will my child receive?

- How is progress measured?

- Will my child's behavior be closely observed and recorded?

- Will my child be given tasks and rewards that are personally motivating?

- Is the environment designed to minimize distractions?

- Will the program prepare me to continue the therapy at home?

- What is the cost, time commitment, and location of the program?

Among the many methods available for treatment and education of people with autism, applied behavior analysis (ABA) has become widely accepted as an effective treatment. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General states, "Thirty years of research demonstrated the efficacy of applied behavioral methods in reducing inappropriate behavior and in increasing communication, learning, and appropriate social behavior." 18 The basic research done by Ivar Lovaas and his colleagues at the University of California, Los Angeles, calling for an intensive, one-on-one child-professional interaction for 40 hours a week, laid a foundation for other educators and researchers in the search for further effective early interventions to help those with ASD attain their potential. The goal of behavioral management is to reinforce desirable behaviors and reduce undesirable ones. 19 , 20 An effective treatment program will build on the child's interests, offer a predictable schedule, teach tasks as a series of simple steps, actively engage the child's attention in highly structured activities, and provide regular reinforcement of behavior. Parental involvement has emerged as a major factor in treatment success. Parents work with professionals and therapists to identify the behaviors to be changed and the skills to be taught. Recognizing that parents are the child's earliest professionals, more programs are beginning to train parents to continue the therapy at home. As soon as a child's disability has been identified, instruction should begin. Effective programs will teach early communication and social interaction skills. In children younger than 3 years, appropriate interventions usually take place in the home or a child care center. These interventions target specific deficits in learning, language, imitation, attention, motivation, compliance, and initiative of interaction. Included are behavioral methods, communication, occupational and physical therapy along with social play interventions. Often the day will begin with a physical activity to help develop coordination and body awareness; children string beads, piece puzzles together, paint, and participate in other motor skills activities. At snack time the professional encourages social interaction and models how to use language to ask for more juice. The children learn by doing. Working with the children are students, behavioral therapists, and parents who have received extensive training. In teaching the children, positive reinforcement is used. 21 Children older than 3 years usually have school-based, individualized, special education. The child may be in a segregated class with other autistic children or in an integrated class with children without disabilities for at least part of the day. Different localities may use differing methods but all should provide a structure that will help the children learn social skills and functional communication. In these programs, professionals often involve the parents, giving useful advice in how to help their child use the skills or behaviors learned at school when they are at home. 22 In elementary school, the child should receive help in any skill area that is delayed and, at the same time, be encouraged to grow in his or her areas of strength. Ideally, the curriculum should be adapted to the individual child's needs. Many schools today have an inclusion program in which the child is in a regular classroom for most of the day, with special instruction for a part of the day. This instruction should include such skills as learning how to act in social situations and in making friends. Although higher-functioning children may be able to handle academic work, they too need help to organize tasks and avoid distractions. During middle and high school years, instruction will begin to address such practical matters as work, community living, and recreational activities. This should include work experience, using public transportation, and learning skills that will be important in community living. 23 All through your child's school years, you will want to be an active participant in his or her education program. Collaboration between parents and educators is essential in evaluating your child's progress.

The Adolescent Years

Adolescence is a time of stress and confusion; and it is no less so for teenagers with autism. Like all children, they need help in dealing with their budding sexuality. While some behaviors improve during the teenage years, some get worse. Increased autistic or aggressive behavior may be one way some teens express their newfound tension and confusion.

The teenage years are also a time when children become more socially sensitive. At the age that most teenagers are concerned with acne, popularity, grades, and dates, teens with autism may become painfully aware that they are different from their peers. They may notice that they lack friends. And unlike their schoolmates, they aren't dating or planning for a career. For some, the sadness that comes with such realization motivates them to learn new behaviors and acquire better social skills.

Dietary and Other Interventions

In an effort to do everything possible to help their children, many parents continually seek new treatments. Some treatments are developed by reputable therapists or by parents of a child with ASD. Although an unproven treatment may help one child, it may not prove beneficial to another. To be accepted as a proven treatment, the treatment should undergo clinical trials, preferably randomized, double-blind trials, that would allow for a comparison between treatment and no treatment. Following are some of the interventions that have been reported to have been helpful to some children but whose efficacy or safety has not been proven.

Dietary interventions are based on the idea that 1) food allergies cause symptoms of autism, and 2) an insufficiency of a specific vitamin or mineral may cause some autistic symptoms. If parents decide to try for a given period of time a special diet, they should be sure that the child's nutritional status is measured carefully.

A diet that some parents have found was helpful to their autistic child is a gluten-free, casein-free diet. Gluten is a casein-like substance that is found in the seeds of various cereal plants—wheat, oat, rye, and barley. Casein is the principal protein in milk. Since gluten and milk are found in many of the foods we eat, following a gluten-free, casein-free diet is difficult.

A supplement that some parents feel is beneficial for an autistic child is Vitamin B6, taken with magnesium (which makes the vitamin effective). The result of research studies is mixed; some children respond positively, some negatively, some not at all or very little. 4

In the search for treatment for autism, there has been discussion in the last few years about the use of secretin, a substance approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for a single dose normally given to aid in diagnosis of a gastrointestinal problem. Anecdotal reports have shown improvement in autism symptoms, including sleep patterns, eye contact, language skills, and alertness. Several clinical trials conducted in the last few years have found no significant improvements in symptoms between patients who received secretin and those who received a placebo. 24

Medication Used In Treatment

Medications are often used to treat behavioral problems, such as aggression, self-injurious behavior, and severe tantrums, that keep the person with ASD from functioning more effectively at home or school. The medications used are those that have been developed to treat similar symptoms in other disorders. Many of these medications are prescribed "off-label." This means they have not been officially approved by the FDA for use in children, but the doctor prescribes the medications if he or she feels they are appropriate for your child. Further research needs to be done to ensure not only the efficacy but the safety of psychotropic agents used in the treatment of children and adolescents.

A child with ASD may not respond in the same way to medications as typically developing children. It is important that parents work with a doctor who has experience with children with autism. A child should be monitored closely while taking a medication. The doctor will prescribe the lowest dose possible to be effective. Ask the doctor about any side effects the medication may have and keep a record of how your child responds to the medication. It will be helpful to read the "patient insert" that comes with your child's medication. Some people keep the patient inserts in a small notebook to be used as a reference. This is most useful when several medications are prescribed.

Anxiety and depression. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI's) are the medications most often prescribed for symptoms of anxiety, depression, and/or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Only one of the SSRI's, fluoxetine, (Prozac®) has been approved by the FDA for both OCD and depression in children age 7 and older. Three that have been approved for OCD are fluvoxamine (Luvox®), age 8 and older; sertraline (Zoloft®), age 6 and older; and clomipramine (Anafranil®), age 10 and older.4 Treatment with these medications can be associated with decreased frequency of repetitive, ritualistic behavior and improvements in eye contact and social contacts. The FDA is studying and analyzing data to better understand how to use the SSRI's safely, effectively, and at the lowest dose possible.