Educators Battle Plagiarism As 89% Of Students Admit To Using OpenAI’s ChatGPT For Homework

Who's teaching who?

A large majority of students are already using ChatGPT for homework assignments, creating challenges around plagiarism , cheating, and learning. According to Wharton MBA Professor Christian Terwisch, ChatGPT would receive “a B or a B-” on an Ivy League MBA-level exam in operations management. Another professor at a Utah-based university asked ChatGPT to tweet in his voice - leading Professor Alex Lawrence to declare that “this is the greatest cheating tool ever invented”, according to the Wall Street Journal . The plagiarism potential is potent - so, is banning the tool a realistic solution?

New research from Study.com provides eye-opening insight into the educational impact of ChatGPT , an online tool that has a surprising mastery of learning and human language. INSIDER reports that researchers recently put ChatGPT through the United States Medical Licensing exam (the three-part exam used to qualify medical school students for residency - basically, a test to see if you can be a doctor). In a December report, ChatGPT “performed at or near the passing threshold for all three exams without any training or reinforcement.” Lawrence, a professor from Weber State in Utah who tested via tweet, wrote a follow-up message to his students regarding the new platform from OpenAI: “I hope to inspire and educate you enough that you will want to learn how to leverage these tools, not just to learn to cheat better.” No word on how the students have responded so far.

Machines, tools and software have been making certain tasks easier for us for thousands of years. Are we about to outsource learning and education to artificial intelligence ? And what are the implications, beyond the classroom, if we do?

Considering that 90% of students are aware of ChatGPT, and 89% of survey respondents report that they have used the platform to help with a homework assignment, the application of OpenAI’s platform is already here. More from the survey:

- 48% of students admitted to using ChatGPT for an at-home test or quiz, 53% had it write an essay, and 22% had it write an outline for a paper.

- 72% of college students believe that ChatGPT should be banned from their college's network. (New York, Seattle and Los Angeles have all blocked the service from their public school networks).

- 82% of college professors are aware of ChatGPT

- 72% of college professors who are aware of ChatGPT are concerned about its impact on cheating

- Over a third (34%) of all educators believe that ChatGPT should be banned in schools and universities, while 66% support students having access to it.

- Meanwhile, 5% of educators say that they have used ChatGPT to teach a class, and 7% have used the platform to create writing prompts.

A teacher quoted anonymously in the Study.com survey shares, “'I love that students would have another resource to help answer questions. Do I worry some kids would abuse it? Yes. But they use Google and get answers without an explanation. It's my understanding that ChatGPT explains answers. That [explanation] would be more beneficial.” Or would it become a crutch?

Modern society has many options for transportation: cars, planes, trains, and even electric scooters all help us to get around. But these machines haven’t replaced the simple fact that walking and running (on your own) is really, really good for you. Electric bikes are fun, but pushing pedals on our own is where we find our fitness. Without movement comes malady. A sedentary life that relies solely on external mechanisms for transport is a recipe for atrophy, poor health, and even a shortened lifespan. Will ChatGPT create educational atrophy, the equivalent of an electric bicycle for our brains?

Of course, when calculators came into the classroom, many declared the decline of math skills would soon follow. Research conducted as recently as 2012 has proven this to be false. Calculators had no positive or negative effects on basic math skills.

But ChatGPT has already gone beyond the basics, passing medical exams and MBA-level tests. A brave new world is already here, with implications for cheating and plagiarism, to be sure. But an even deeper implication points to the very nature of learning itself, when ChatGPT has become a super-charged repository for what is perhaps the most human of all inventions: the synthesis of our language. (That same synthesis that sits atop Blooms Taxonomy - a revered pyramid of thinking, that outlines the path to higher learning ). Perhaps educators, students and even business leaders will discover something old is new again, from ChatGPT. That discovery? Seems Socrates was right: the key to strong education begins with asking the right questions. Especially if you are talking to a ‘bot.

Back-to-school for higher education sees students and professors grappling with AI in academia

America’s colleges have an AI dilemma, but students are embracing it.

As millions of students return to school this fall, ABC News spoke with students and professors learning to navigate the influence of generative artificial intelligence.

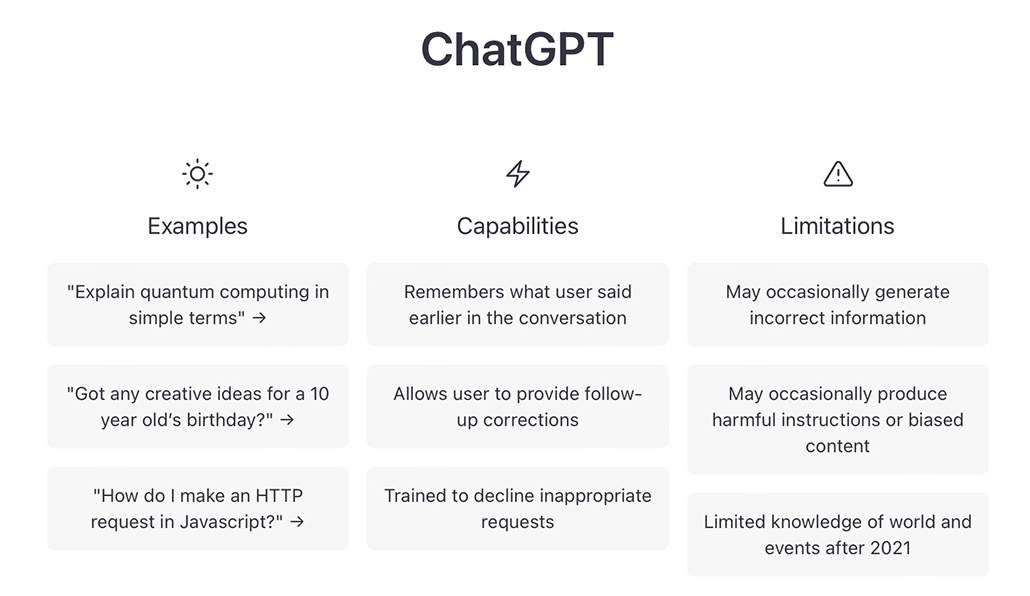

ChatGPT, which launched in November 2022, is described on its website as an AI-powered language model, "capable of generating human-like text based on context and past conversations."

At the University of California, Davis, senior Andrew Yu found himself using AI to help outline an eight-page paper for his poetry class. It needed to be in the style of an academic memorandum, which Yu had never written before -- so he turned to ChatGPT to help him visualize the project.

"I think it's kind of ironic or it's a really funny thing because I'm an English major," Yu told ABC News.

MORE: Amid spread of AI tools, new digital standard would help users tell fact from fiction

Yu says he is careful to use ChatGPT technology to template and structure his assignments but not go beyond that. "I feel like it's not authentic to me in the way that I write, so I just use it as a skeleton, like an outline," he said.

"Sometimes we get a little stuck and need extra help," said Eneesa Abdullah-Hudson, a senior at Morgan State University, a historically Black college in Baltimore. "So just having this tool here to help guide us, so we can add our feedback with it, it's definitely helpful."

Among U.S. adults who have heard of ChatGPT, only 41% between ages 18 and 29 have used it, according to Pew Research data . Now, professors across the country are learning alongside their students about the risks and rewards of generative AI in education.

University of Florida Warrington College of Business Professor Dr. Joel Davis said AI innovations like ChatGPT could be used as a tool for core language arts subjects.

"There's a natural progression," Davis, who researches the integration of generative AI solutions, told ABC News. "New tools like the calculator, like Grammarly and editing tools that came out a number of years ago that made all of our writing better, including mine, right? Those are things that are just going to keep on coming. And, we can't stop them from coming, but it's up to us to decide how to integrate them appropriately."

Despite using AI himself, Yu says he is cautious and concerned by the quality of AI responses.

MORE: As acceptance rates decline, students bill themselves as admissions experts

"It's definitely like a risk," Yu said, adding "I feel like it can be beneficial. You just have to use it responsibly and make sure that the majority of your wording is you, and none of it is by the AI."

Does AI promote or detect cheating?

Most schools are embracing the novelty of generative AI use by teachers and students, but some faculty are already facing the issue of it interfering with assignments in their classrooms.

Davis demoed AI's abilities with his own tests.

"It does fairly well on my exams," he said. "It can recite those answers pretty well, but I don't view that as a ChatGPT problem; that's my issue."

Furman University Professor Darren Hick had a hunch that one of his students used AI to write a final paper last December.

Hick said the student sat in his Greenville, South Carolina, office, hyperventilating, before confessing to using ChatGPT.

"We're not ready for it [AI chatbot cheating]," Hick, who gave this student a failing grade, told ABC News. "We're not prepared to deal with this. It's just harder to catch. That's always been my concern."

Furman's current definition of plagiarism is "copying word for word from another source without proper attribution." These instances, when AI use is detected, could be considered "inappropriate collaboration or cheating," a school spokesperson said.

An OpenAI spokesperson also said the company that powers ChatGPT has always called for "transparency" around generative AI use. Davis, at the University of Florida, told ABC News that assessments need to change if educators are worried about students using chatbots to cheat.

But Jessica Zimny, a junior at Midwestern State University in Wichita Falls, Texas, told ABC News she earned perfect scores on her political science discussion posts until her account was flagged for AI-assistance detection.

"I noticed that when I logged in, it said that I had a zero for that assignment, and to the right of it was a note stating that Turnitin detected AI use on my assignment," Zimny said.

Turnitin, a popular resource used by schools to check for plagiarism within student assignments, searches text for signs it was generated by AI. When AI detection is indicated, the company recommends that teachers have conversations with their students and this will usually "resolve" the issue one way or another.

Even though Zimny claimed she didn't use AI, she said her professor failed her because the program flagged her assignment.

"It's just really frustrating," Zimny said. "I just hate the fact that there are actually people out there that do use AI and do cheat to where you have to get to the point where there have to be detectors that are made that can falsely accuse people who aren't in the wrong."

ABC News reached out to Midwestern State for a comment on Zimny's failing grade. Interim Provost Dr. Marcy Brown Marsden said she's unable to speak directly to a student's academic record or appeals due to FERPA regulations. On the school's public directory, it says if Turnitin.com detects that an assignment was completed using AI, the student will be given a grade of zero for that assignment.

However, Turnitin leaves the final decision-making to the instructor.

"Teachers should be using similarity reports and AI reports as resources, not deciders," Annie Chechitelli, chief product officer at Turnitin, told ABC News in a statement.

Aside from plagiarism concerns, there is also worry about the security of data entered by students and teachers into generative AI tools.

"It is indeed entirely possible, and indeed likely, that bad actors will use open source large language models - which students may well use – to obtain sensitive personal data, for the purposes of targeting advertising, blackmail, and so forth," "Rebooting AI" author Gary Marcus told ABC News.

New York City Public Schools placed ChatGPT on its list of restricted websites, though it is still accessible if schools request it. However, in a statement on Chalkbeat , Chancellor of New York City Public Schools David C. Banks said, "The knee-jerk fear and risk overlooked the potential of generative AI to support students and teachers, as well as the reality that our students are participating in and will work in a world where understanding generative AI is crucial."

Is AI avoidable?

Generative AI has become the new frontier for educators and students to work around. Some universities said there's no one-size-fits-all approach while others have strict guidelines to combat unethical usage.

Carnegie Mellon University's (CMU) Academic Integrity Policy prohibits "unauthorized assistance," which would include generative AI tools unless explicitly permitted by the instructor, according to a recent letter published by the school's leaders. Most colleges -- like CMU -- still embrace the novelty of generative AI use by teachers and students.

"I think for probably the first time, nine months ago when OpenAI put out the ChatGPT, it [AI] sort of allowed an average person to kind of touch and feel it, to explore it, to try it," AI Scholar and CMU Professor Rayid Ghani told ABC News. "It wasn't something we could touch and feel and do. We weren't using it ourselves."

Abdullah-Hudson said she uses ChatGPT to check her work. "It's just like an extra helping tool."

And, OpenAI invites teachers to use its technology. The company's Teaching with AI page suggests prompts to help teachers come up with lesson plans. Embracing AI, Abdullah-Hudson believes it's here to stay.

"Living in the world today, there's no way around it," Abdullah-Hudson said. "So there's no way to avoid the AI, might as well learn to use it instead of being afraid of it."

Related Topics

- Artificial Intelligence

Popular Reads

Harris paints Trump as a threat on Fox News

- Oct 16, 7:17 PM

Possible bear attack was actually vicious murder

- Oct 17, 5:12 PM

Singer Liam Payne dies after hotel fall: Police

- Oct 16, 6:38 PM

The US trained him to fight, but he turned on it

- Oct 17, 5:11 AM

16-year-old girl's head and hands found in freezer

- Oct 12, 1:10 AM

ABC News Live

24/7 coverage of breaking news and live events

It’s a wonderful world — and universe — out there.

Come explore with us!

Science News Explores

Think twice before using chatgpt for help with homework.

This new AI tool talks a lot like a person — but still makes mistakes

ChatGPT is impressive and can be quite useful. It can help people write text, for instance, and code. However, “it’s not magic,” says Casey Fiesler. In fact, it often seems intelligent and confident while making mistakes — and sometimes parroting biases.

Glenn Harvey

Share this:

- Google Classroom

By Kathryn Hulick

February 16, 2023 at 6:30 am

“We need to talk,” Brett Vogelsinger said. A student had just asked for feedback on an essay. One paragraph stood out. Vogelsinger, a 9th-grade English teacher in Doylestown, Pa., realized that the student hadn’t written the piece himself. He had used ChatGPT. It’s a new artificial intelligence (AI) tool. It answers questions. It writes code. And it can generate long essays and stories.

The company OpenAI made ChatGPT available for free at the end of November 2022. Within a week, it had more than a million users. Other tech companies are racing to put out similar tools. Google launched Bard in early February. The AI company Anthropic is testing a new chatbot named Claude. And another AI company, DeepMind, is working on a bot called Sparrow.

ChatGPT marks the beginning of a new wave of AI that will disrupt education. Whether that’s a good or bad thing remains to be seen.

Some people have been using ChatGPT out of curiosity or for entertainment. I asked it to invent a silly excuse for not doing homework in the style of a medieval proclamation. In less than a second, it offered me: “Hark! Thy servant was beset by a horde of mischievous leprechauns, who didst steal mine quill and parchment, rendering me unable to complete mine homework.”

But students can also use it to cheat. When Stanford University’s student-run newspaper polled students at the university, 17 percent said they had used ChatGPT on assignments or exams during the end of 2022. Some admitted to submitting the chatbot’s writing as their own. For now, these students and others are probably getting away with cheating.

And that’s because ChatGPT does an excellent job. “It can outperform a lot of middle-school kids,” Vogelsinger says. He probably wouldn’t have known his student used it — except for one thing. “He copied and pasted the prompt,” says Vogelsinger.

This essay was still a work in progress. So Vogelsinger didn’t see this as cheating. Instead, he saw an opportunity. Now, the student is working with the AI to write that essay. It’s helping the student develop his writing and research skills.

“We’re color-coding,” says Vogelsinger. The parts the student writes are in green. Those parts that ChatGPT writes are in blue. Vogelsinger is helping the student pick and choose only a few sentences from the AI to keep. He’s allowing other students to collaborate with the tool as well. Most aren’t using it regularly, but a few kids really like it. Vogelsinger thinks it has helped them get started and to focus their ideas.

This story had a happy ending.

But at many schools and universities, educators are struggling with how to handle ChatGPT and other tools like it. In early January, New York City public schools banned ChatGPT on their devices and networks. They were worried about cheating. They also were concerned that the tool’s answers might not be accurate or safe. Many other school systems in the United States and elsewhere have followed suit.

Test yourself: Can you spot the ChatGPT answers in our quiz?

But some experts suspect that bots like ChatGPT could also be a great help to learners and workers everywhere. Like calculators for math or Google for facts, an AI chatbot makes something that once took time and effort much simpler and faster. With this tool, anyone can generate well-formed sentences and paragraphs — even entire pieces of writing.

How could a tool like this change the way we teach and learn?

The good, the bad and the weird

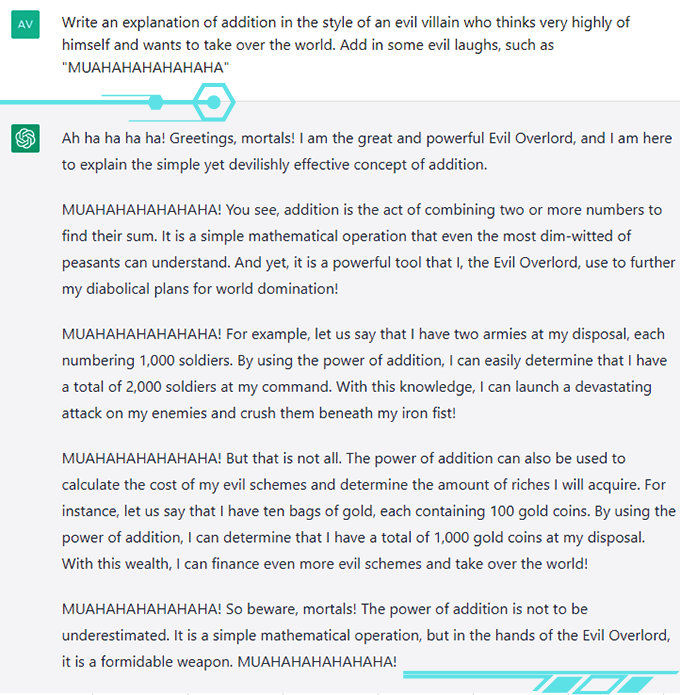

ChatGPT has wowed its users. “It’s so much more realistic than I thought a robot could be,” says Avani Rao. This high school sophomore lives in California. She hasn’t used the bot to do homework. But for fun, she’s prompted it to say creative or silly things. She asked it to explain addition, for instance, in the voice of an evil villain. Its answer is highly entertaining.

Tools like ChatGPT could help create a more equitable world for people who are trying to work in a second language or who struggle with composing sentences. Students could use ChatGPT like a coach to help improve their writing and grammar. Or it could explain difficult subjects. “It really will tutor you,” says Vogelsinger, who had one student come to him excited that ChatGPT had clearly outlined a concept from science class.

Teachers could use ChatGPT to help create lesson plans or activities — ones personalized to the needs or goals of specific students.

Several podcasts have had ChatGPT as a “guest” on the show. In 2023, two people are going to use an AI-powered chatbot like a lawyer. It will tell them what to say during their appearances in traffic court. The company that developed the bot is paying them to test the new tech. Their vision is a world in which legal help might be free.

@professorcasey Replying to @novshmozkapop #ChatGPT might be helpful but don’t ask it for help on your math homework. #openai #aiethics ♬ original sound – Professor Casey Fiesler

Xiaoming Zhai tested ChatGPT to see if it could write an academic paper . Zhai is an expert in science education at the University of Georgia in Athens. He was impressed with how easy it was to summarize knowledge and generate good writing using the tool. “It’s really amazing,” he says.

All of this sounds great. Still, some really big problems exist.

Most worryingly, ChatGPT and tools like it sometimes gets things very wrong. In an ad for Bard, the chatbot claimed that the James Webb Space Telescope took the very first picture of an exoplanet. That’s false. In a conversation posted on Twitter, ChatGPT said the fastest marine mammal was the peregrine falcon. A falcon, of course, is a bird and doesn’t live in the ocean.

ChatGPT can be “confidently wrong,” says Casey Fiesler. Its text, she notes, can contain “mistakes and bad information.” She is an expert in the ethics of technology at the University of Colorado Boulder. She has made multiple TikTok videos about the pitfalls of ChatGPT .

Also, for now, all of the bot’s training data came from before a date in 2021. So its knowledge is out of date.

Finally, ChatGPT does not provide sources for its information. If asked for sources, it will make them up. It’s something Fiesler revealed in another video . Zhai discovered the exact same thing. When he asked ChatGPT for citations, it gave him sources that looked correct. In fact, they were bogus.

Zhai sees the tool as an assistant. He double-checked its information and decided how to structure the paper himself. If you use ChatGPT, be honest about it and verify its information, the experts all say.

Under the hood

ChatGPT’s mistakes make more sense if you know how it works. “It doesn’t reason. It doesn’t have ideas. It doesn’t have thoughts,” explains Emily M. Bender. She is a computational linguist who works at the University of Washington in Seattle. ChatGPT may sound a lot like a person, but it’s not one. It is an AI model developed using several types of machine learning .

The primary type is a large language model. This type of model learns to predict what words will come next in a sentence or phrase. It does this by churning through vast amounts of text. It places words and phrases into a 3-D map that represents their relationships to each other. Words that tend to appear together, like peanut butter and jelly, end up closer together in this map.

Before ChatGPT, OpenAI had made GPT3. This very large language model came out in 2020. It had trained on text containing an estimated 300 billion words. That text came from the internet and encyclopedias. It also included dialogue transcripts, essays, exams and much more, says Sasha Luccioni. She is a researcher at the company HuggingFace in Montreal, Canada. This company builds AI tools.

OpenAI improved upon GPT3 to create GPT3.5. This time, OpenAI added a new type of machine learning. It’s known as “reinforcement learning with human feedback.” That means people checked the AI’s responses. GPT3.5 learned to give more of those types of responses in the future. It also learned not to generate hurtful, biased or inappropriate responses. GPT3.5 essentially became a people-pleaser.

During ChatGPT’s development, OpenAI added even more safety rules to the model. As a result, the chatbot will refuse to talk about certain sensitive issues or information. But this also raises another issue: Whose values are being programmed into the bot, including what it is — or is not — allowed to talk about?

OpenAI is not offering exact details about how it developed and trained ChatGPT. The company has not released its code or training data. This disappoints Luccioni. “I want to know how it works in order to help make it better,” she says.

When asked to comment on this story, OpenAI provided a statement from an unnamed spokesperson. “We made ChatGPT available as a research preview to learn from real-world use, which we believe is a critical part of developing and deploying capable, safe AI systems,” the statement said. “We are constantly incorporating feedback and lessons learned.” Indeed, some early experimenters got the bot to say biased things about race and gender. OpenAI quickly patched the tool. It no longer responds the same way.

ChatGPT is not a finished product. It’s available for free right now because OpenAI needs data from the real world. The people who are using it right now are their guinea pigs. If you use it, notes Bender, “You are working for OpenAI for free.”

Humans vs robots

How good is ChatGPT at what it does? Catherine Gao is part of one team of researchers that is putting the tool to the test.

At the top of a research article published in a journal is an abstract. It summarizes the author’s findings. Gao’s group gathered 50 real abstracts from research papers in medical journals. Then they asked ChatGPT to generate fake abstracts based on the paper titles. The team asked people who review abstracts as part of their job to identify which were which .

The reviewers mistook roughly one in every three (32 percent) of the AI-generated abstracts as human-generated. “I was surprised by how realistic and convincing the generated abstracts were,” says Gao. She is a doctor and medical researcher at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Ill.

In another study, Will Yeadon and his colleagues tested whether AI tools could pass a college exam . Yeadon is a physics teacher at Durham University in England. He picked an exam from a course that he teaches. The test asks students to write five short essays about physics and its history. Students who take the test have an average score of 71 percent, which he says is equivalent to an A in the United States.

Yeadon used a close cousin of ChatGPT, called davinci-003. It generated 10 sets of exam answers. Afterward, he and four other teachers graded them using their typical grading standards for students. The AI also scored an average of 71 percent. Unlike the human students, however, it had no very low or very high marks. It consistently wrote well, but not excellently. For students who regularly get bad grades in writing, Yeadon says, this AI “will write a better essay than you.”

These graders knew they were looking at AI work. In a follow-up study, Yeadon plans to use work from the AI and students and not tell the graders whose work they are looking at.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Cheat-checking with AI

People may not always be able to tell if ChatGPT wrote something or not. Thankfully, other AI tools can help. These tools use machine learning to scan many examples of AI-generated text. After training this way, they can look at new text and tell you whether it was most likely composed by AI or a human.

Most free AI-detection tools were trained on older language models, so they don’t work as well for ChatGPT. Soon after ChatGPT came out, though, one college student spent his holiday break building a free tool to detect its work . It’s called GPTZero .

The company Originality.ai sells access to another up-to-date tool. Founder Jon Gillham says that in a test of 10,000 samples of text composed by GPT3, the tool tagged 94 percent of them correctly. When ChatGPT came out, his team tested a much smaller set of 20 samples that had been created by GPT3, GPT3.5 and ChatGPT. Here, Gillham says, “it tagged all of them as AI-generated. And it was 99 percent confident, on average.”

In addition, OpenAI says they are working on adding “digital watermarks” to AI-generated text. They haven’t said exactly what they mean by this. But Gillham explains one possibility. The AI ranks many different possible words when it is generating text. Say its developers told it to always choose the word ranked in third place rather than first place at specific places in its output. These words would act “like a fingerprint,” says Gillham.

The future of writing

Tools like ChatGPT are only going to improve with time. As they get better, people will have to adjust to a world in which computers can write for us. We’ve made these sorts of adjustments before. As high-school student Rao points out, Google was once seen as a threat to education because it made it possible to instantly look up any fact. We adapted by coming up with teaching and testing materials that don’t require students to memorize things.

Now that AI can generate essays, stories and code, teachers may once again have to rethink how they teach and test. That might mean preventing students from using AI. They could do this by making students work without access to technology. Or they might invite AI into the writing process, as Vogelsinger is doing. Concludes Rao, “We might have to shift our point of view about what’s cheating and what isn’t.”

Students will still have to learn to write without AI’s help. Kids still learn to do basic math even though they have calculators. Learning how math works helps us learn to think about math problems. In the same way, learning to write helps us learn to think about and express ideas.

Rao thinks that AI will not replace human-generated stories, articles and other texts. Why? She says: “The reason those things exist is not only because we want to read it but because we want to write it.” People will always want to make their voices heard. ChatGPT is a tool that could enhance and support our voices — as long as we use it with care.

Correction: Gillham’s comment on the 20 samples that his team tested has been corrected to show how confident his team’s AI-detection tool was in identifying text that had been AI-generated (not in how accurately it detected AI-generated text).

Can you find the bot?

More stories from science news explores on tech.

A Jurassic Park -inspired method can safely store data in DNA

Predicting and designing protein structures wins a 2024 Nobel Prize

Explainer: What is generative AI?

ChatGPT and other AI tools are full of hidden racial biases

Two AI trailblazers win the 2024 Nobel Prize in physics

Spacecraft need an extra boost to travel between stars

Weirdly, mayo can help study conditions ripe for nuclear fusion

This biologist tracks seadragons, with help from the public

Articles on Homework

Displaying 1 - 20 of 34 articles.

ChatGPT isn’t the death of homework – just an opportunity for schools to do things differently

Andy Phippen , Bournemouth University

How can I make studying a daily habit?

Deborah Reed , University of Tennessee

Debate: ChatGPT offers unseen opportunities to sharpen students’ critical skills

Erika Darics , University of Groningen and Lotte van Poppel , University of Groningen

Education in Kenya’s informal settlements can work better if parents get involved – here’s how

Benta A. Abuya , African Population and Health Research Center

‘There’s only so far I can take them’ – why teachers give up on struggling students who don’t do their homework

Jessica Calarco , Indiana University and Ilana Horn , Vanderbilt University

Talking with your teen about high school helps them open up about big (and little) things in their lives

Lindsey Jaber , University of Windsor

Primary school children get little academic benefit from homework

Paul Hopkins , University of Hull

How much time should you spend studying? Our ‘Goldilocks Day’ tool helps find the best balance of good grades and well-being

Dot Dumuid , University of South Australia and Tim Olds , University of South Australia

What’s the point of homework?

Katina Zammit , Western Sydney University

4 tips for college students to avoid procrastinating with their online work

Kui Xie , The Ohio State University and Shonn Cheng , Sam Houston State University

Online learning will be hard for kids whose schools close – and the digital divide will make it even harder for some of them

Jessica Calarco , Indiana University

How to help your kids with homework (without doing it for them)

Melissa Barnes , Monash University and Katrina Tour , Monash University

6 ways to establish a productive homework routine

Janine L. Nieroda-Madden , Syracuse University

Should parents help their kids with homework?

Daniel Hamlin , University of Oklahoma

Is homework worthwhile?

Robert H. Tai , University of Virginia

Teachers’ expectations help students to work harder, but can also reduce enjoyment and confidence – new research

Lars-Erik Malmberg , University of Oxford and Andrew J. Martin , UNSW Sydney

More primary schools could scrap homework – a former classroom teacher’s view

Lorele Mackie , University of Stirling

Modern life offers children almost everything they need, except daylight

Vybarr Cregan-Reid , University of Kent

Why students need more ‘math talk’

Matthew Campbell , West Virginia University and Johnna Bolyard , West Virginia University

Neuroscience is unlocking mysteries of the teenage brain

Lucy Foulkes, University of York

Related Topics

- K-12 education

Top contributors

Associate Professor of Sociology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Professor of Educational Administration, Penn State

Associate professor, Pacific Lutheran University

Assistant professor, School of Psychology, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

Clinical psychologist; visiting fellow, Queensland University of Technology

Director, Learning and Teaching Education Research Centre, CQUniversity Australia

Associate Professor of Mathematics Education, West Virginia University

Associate Professor in Language, Literacy and TESL, University of Canberra

Senior Lecturer, School of Education, Curtin University

Lecturer in Education, University of Stirling

Associate Dean, Director Student Conduct and Conflict Resolution, University of Florida

Vice-Chancellor's Fellow, The University of Melbourne

Associate Professor, Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Sydney

Assistant Professor of Secondary Mathematics Education, West Virginia University

Professor of Education, University of Florida

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

- About The Journalist’s Resource

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Basic newswriting: Learn how to originate, research and write breaking-news stories

Syllabus for semester-long course on the fundamentals of covering and writing the news, including how identify a story, gather information efficiently and place it in a meaningful context.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by The Journalist's Resource, The Journalist's Resource January 22, 2010

This course introduces tomorrow’s journalists to the fundamentals of covering and writing news. Mastering these skills is no simple task. In an Internet age of instantaneous access, demand for high-quality accounts of fast-breaking news has never been greater. Nor has the temptation to cut corners and deliver something less.

To resist this temptation, reporters must acquire skills to identify a story and its essential elements, gather information efficiently, place it in a meaningful context, and write concise and compelling accounts, sometimes at breathtaking speed. The readings, discussions, exercises and assignments of this course are designed to help students acquire such skills and understand how to exercise them wisely.

Photo: Memorial to four slain Lakewood, Wash., police officers. The Seattle Times earned the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Reporting for their coverage of the crime.

Course objective

To give students the background and skills needed to originate, research, focus and craft clear, compelling and contextual accounts of breaking news in a deadline environment.

Learning objectives

- Build an understanding of the role news plays in American democracy.

- Discuss basic journalistic principles such as accuracy, integrity and fairness.

- Evaluate how practices such as rooting and stereotyping can undermine them.

- Analyze what kinds of information make news and why.

- Evaluate the elements of news by deconstructing award-winning stories.

- Evaluate the sources and resources from which news content is drawn.

- Analyze how information is attributed, quoted and paraphrased in news.

- Gain competence in focusing a story’s dominant theme in a single sentence.

- Introduce the structure, style and language of basic news writing.

- Gain competence in building basic news stories, from lead through their close.

- Gain confidence and competence in writing under deadline pressure.

- Practice how to identify, background and contact appropriate sources.

- Discuss and apply the skills needed to interview effectively.

- Analyze data and how it is used and abused in news coverage.

- Review basic math skills needed to evaluate and use statistics in news.

- Report and write basic stories about news events on deadline.

Suggested reading

- A standard textbook of the instructor’s choosing.

- America ‘s Best Newspaper Writing , Roy Peter Clark and Christopher Scanlan, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2006

- The Elements of Journalism , Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel, Three Rivers Press, 2001.

- Talk Straight, Listen Carefully: The Art of Interviewing , M.L. Stein and Susan E. Paterno, Iowa State University Press, 2001

- Math Tools for Journalists , Kathleen Woodruff Wickham, Marion Street Press, Inc., 2002

- On Writing Well: 30th Anniversary Edition , William Zinsser, Collins, 2006

- Associated Press Stylebook 2009 , Associated Press, Basic Books, 2009

Weekly schedule and exercises (13-week course)

We encourage faculty to assign students to read on their own Kovach and Rosentiel’s The Elements of Journalism in its entirety during the early phase of the course. Only a few chapters of their book are explicitly assigned for the class sessions listed below.

The assumption for this syllabus is that the class meets twice weekly.

Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 7 Week 8 | Week 9 | Week 10 | Week 11 | Week 12 | Weeks 13/14

Week 1: Why journalism matters

Previous week | Next week | Back to top

Class 1: The role of journalism in society

The word journalism elicits considerable confusion in contemporary American society. Citizens often confuse the role of reporting with that of advocacy. They mistake those who promote opinions or push their personal agendas on cable news or in the blogosphere for those who report. But reporters play a different role: that of gatherer of evidence, unbiased and unvarnished, placed in a context of past events that gives current events weight beyond the ways opinion leaders or propagandists might misinterpret or exploit them.

This session’s discussion will focus on the traditional role of journalism eloquently summarized by Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel in The Elements of Journalism . The class will then examine whether they believe that the journalist’s role has changed or needs to change in today’s news environment. What is the reporter’s role in contemporary society? Is objectivity, sometimes called fairness, an antiquated concept or an essential one, as the authors argue, for maintaining a democratic society? How has the term been subverted? What are the reporter’s fundamental responsibilities? This discussion will touch on such fundamental issues as journalists’ obligation to the truth, their loyalty to the citizens who are their audience and the demands of their discipline to verify information, act independently, provide a forum for public discourse and seek not only competing viewpoints but carefully vetted facts that help establish which viewpoints are grounded in evidence.

Reading: Kovach and Rosenstiel, Chapter 1, and relevant pages of the course text

Assignments:

- Students should compare the news reporting on a breaking political story in The Wall Street Journal , considered editorially conservative, and The New York Times , considered editorially liberal. They should write a two-page memo that considers the following questions: Do the stories emphasize the same information? Does either story appear to slant the news toward a particular perspective? How? Do the stories support the notion of fact-based journalism and unbiased reporting or do they appear to infuse opinion into news? Students should provide specific examples that support their conclusions.

- Students should look for an example of reporting in any medium in which reporters appear have compromised the notion of fairness to intentionally or inadvertently espouse a point of view. What impact did the incorporation of such material have on the story? Did its inclusion have any effect on the reader’s perception of the story?

Class 2: Objectivity, fairness and contemporary confusion about both

In his book Discovering the News , Michael Schudson traced the roots of objectivity to the era following World War I and a desire by journalists to guard against the rapid growth of public relations practitioners intent on spinning the news. Objectivity was, and remains, an ideal, a method for guarding against spin and personal bias by examining all sides of a story and testing claims through a process of evidentiary verification. Practiced well, it attempts to find where something approaching truth lies in a sea of conflicting views. Today, objectivity often is mistaken for tit-for-tat journalism, in which the reporters only responsibility is to give equal weight to the conflicting views of different parties without regard for which, if any, are saying something approximating truth. This definition cedes the journalist’s responsibility to seek and verify evidence that informs the citizenry.

Focusing on the “Journalism of Verification” chapter in The Elements of Journalism , this class will review the evolution and transformation of concepts of objectivity and fairness and, using the homework assignment, consider how objectivity is being practiced and sometimes skewed in the contemporary new media.

Reading: Kovach and Rosenstiel, Chapter 4, and relevant pages of the course text.

Assignment: Students should evaluate stories on the front page and metro front of their daily newspaper. In a two-page memo, they should describe what elements of news judgment made the stories worthy of significant coverage and play. Finally, they should analyze whether, based on what else is in the paper, they believe the editors reached the right decision.

Week 2: Where news comes from

Class 1: News judgment

When editors sit down together to choose the top stories, they use experience and intuition. The beginner journalist, however, can acquire a sense of news judgment by evaluating news decisions through the filter of a variety of factors that influence news play. These factors range from traditional measures such as when the story took place and how close it was to the local readership area to more contemporary ones, such as the story’s educational value.

Using the assignment and the reading, students should evaluate what kinds of information make for interesting news stories and why.

In this session, instructors might consider discussing the layers of news from the simplest breaking news event to the purely enterprise investigative story.

Assignment: Students should read and deconstruct coverage of a major news event. One excellent source for quality examples is the site of the Pulitzer Prizes , which has a category for breaking news reporting. All students should read the same article (assigned by the instructor), and write a two- or three-page memo that describes how the story is organized, what information it contains and what sources of information it uses, both human and digital. Among the questions they should ask are:

- Does the first (or lead) paragraph summarize the dominant point?

- What specific information does the lead include?

- What does it leave out?

- How do the second and third paragraphs relate to the first paragraph and the information it contains? Do they give unrelated information, information that provides further details about what’s established in the lead paragraph or both?

- Does the story at any time place the news into a broader context of similar events or past events? If so, when and how?

- What information in the story is attributed , specifically tied to an individual or to documentary information from which it was taken? What information is not attributed? Where does the information appear in the sentence? Give examples of some of the ways the sources of information are identified? Give examples of the verbs of attribution that are chosen.

- Where and how often in the story are people quoted, their exact words placed in quotation marks? What kind of information tends to be quoted — basic facts or more colorful commentary? What information that’s attributed is paraphrased , summing up what someone said but not in their exact words.

- How is the story organized — by theme, by geography, by chronology (time) or by some other means?

- What human sources are used in the story? Are some authorities? Are some experts? Are some ordinary people affected by the event? Who are some of the people in each category? What do they contribute to the story? Does the reporter (or reporters) rely on a single source or a wide range? Why do you think that’s the case?

- What specific facts and details make the story more vivid to you? How do you think the reporter was able to gather those details?

- What documents (paper or digital) are detailed in the story? Do they lend authority to the story? Why or why not?

- Is any specific data (numbers, statistics) used in the story? What does it lend to the story? Would you be satisfied substituting words such as “many” or “few” for the specific numbers and statistics used? Why or why not?

Class 2: Deconstructing the story

By carefully deconstructing major news stories, students will begin to internalize some of the major principles of this course, from crafting and supporting the lead of a story to spreading a wide and authoritative net for information. This class will focus on the lessons of a Pulitzer Prize winner.

Reading: Clark/Scanlan, Pages 287-294

Assignment: Writers typically draft a focus statement after conceiving an idea and conducting preliminary research or reporting. This focus statement helps to set the direction of reporting and writing. Sometimes reporting dictates a change of direction. But the statement itself keeps the reporter from getting off course. Focus statements typically are 50 words or less and summarize the story’s central point. They work best when driven by a strong, active verb and written after preliminary reporting.

- Students should write a focus statement that encapsulates the news of the Pulitzer Prize winning reporting the class critiqued.

Week 3: Finding the focus, building the lead

Class 1: News writing as a process

Student reporters often conceive of writing as something that begins only after all their reporting is finished. Such an approach often leaves gaps in information and leads the reporter to search broadly instead of with targeted depth. The best reporters begin thinking about story the minute they get an assignment. The approach they envision for telling the story informs their choice of whom they seek interviews with and what information they gather. This class will introduce students to writing as a process that begins with story concept and continues through initial research, focus, reporting, organizing and outlining, drafting and revising.

During this session, the class will review the focus statements written for homework in small breakout groups and then as a class. Professors are encouraged to draft and hand out a mock or real press release or hold a mock press conference from which students can draft a focus statement.

Reading: Zinsser, pages 1-45, Clark/Scanlan, pages 294-302, and relevant pages of the course text

Class 2: The language of news

Newswriting has its own sentence structure and syntax. Most sentences branch rightward, following a pattern of subject/active verb/object. Reporters choose simple, familiar words. They write spare, concise sentences. They try to make a single point in each. But journalistic writing is specific and concrete. While reporters generally avoid formal or fancy word choices and complex sentence structures, they do not write in generalities. They convey information. Each sentence builds on what came before. This class will center on the language of news, evaluating the language in selections from America’s Best Newspaper Writing , local newspapers or the Pulitzers.

Reading: Relevant pages of the course text

Assignment: Students should choose a traditional news lead they like and one they do not like from a local or national newspaper. In a one- or two-page memo, they should print the leads, summarize the stories and evaluate why they believe the leads were effective or not.

Week 4: Crafting the first sentence

Class 1: The lead

No sentence counts more than a story’s first sentence. In most direct news stories, it stands alone as the story’s lead. It must summarize the news, establish the storyline, convey specific information and do all this simply and succinctly. Readers confused or bored by the lead read no further. It takes practice to craft clear, concise and conversational leads. This week will be devoted to that practice.

Students should discuss the assigned leads in groups of three or four, with each group choosing one lead to read to the entire class. The class should then discuss the elements of effective leads (active voice; active verb; single, dominant theme; simple sentences) and write leads in practice exercises.

Assignment: Have students revise the leads they wrote in class and craft a second lead from fact patterns.

Class 2: The lead continued

Some leads snap or entice instead of summarize. When the news is neither urgent nor earnest, these can work well. Though this class will introduce students to other kinds of leads, instructors should continue to emphasize traditional leads, typically found atop breaking news stories.

Class time should largely be devoted to writing traditional news leads under a 15-minute deadline pressure. Students should then be encouraged to read their own leads aloud and critique classmates’ leads. At least one such exercise might focus on students writing a traditional lead and a less traditional lead from the same information.

Assignment: Students should find a political or international story that includes various types (direct and indirect) and levels (on-the-record, not for attribution and deep background) of attribution. They should write a one- or two-page memo describing and evaluating the attribution. Did the reporter make clear the affiliation of those who expressed opinions? Is information attributed to specific people by name? Are anonymous figures given the opportunity to criticize others by name? Is that fair?

Week 5: Establishing the credibility of news

Class 1: Attribution

All news is based on information, painstakingly gathered, verified and checked again. Even so, “truth” is an elusive concept. What reporters cobble together instead are facts and assertions drawn from interviews and documentary evidence.

To lend authority to this information and tell readers from where it comes, reporters attribute all information that is not established fact. It is neither necessary, for example, to attribute that Franklin Delano Roosevelt was first elected president in 1932 nor that he was elected four times. On the other hand, it would be necessary to attribute, at least indirectly, the claim that he was one of America’s best presidents. Why? Because that assertion is a matter of opinion.

In this session, students should learn about different levels of attribution, where attribution is best placed in a sentence, and why it can be crucial for the protection of the accused, the credibility of reporters and the authoritativeness of the story.

Assignment: Working from a fact pattern, students should write a lead that demands attribution.

Class 2: Quoting and paraphrasing

“Great quote,” ranks closely behind “great lead” in the pecking order of journalistic praise. Reporters listen for great quotes as intensely as piano tuners listen for the perfect pitch of middle C. But what makes a great quote? And when should reporters paraphrase instead?

This class should cover a range of issues surrounding the quoted word from what it is used to convey (color and emotion, not basic information) to how frequently quotes should be used and how long they should run on. Other issues include the use and abuse of partial quotes, when a quote is not a quote, and how to deal with rambling and ungrammatical subjects.

As an exercise, students might either interview the instructor or a classmate about an exciting personal experience. After their interviews, they should review their notes choose what they consider the three best quotes to include a story on the subject. They should then discuss why they chose them.

Assignment: After completing the reading, students should analyze a summary news story no more than 15 paragraphs long. In a two- or three-page memo, they should reprint the story and then evaluate whether the lead summarizes the news, whether the subsequent paragraphs elaborate on or “support” the lead, whether the story has a lead quote, whether it attributes effectively, whether it provides any context for the news and whether and how it incorporates secondary themes.

Week 6: The building blocks of basic stories

Class 1: Supporting the lead

Unlike stories told around a campfire or dinner table, news stories front load information. Such a structure delivers the most important information first and the least important last. If a news lead summarizes, the subsequent few paragraphs support or elaborate by providing details the lead may have merely suggested. So, for example, a story might lead with news that a 27-year-old unemployed chef has been arrested on charges of robbing the desk clerk of an upscale hotel near closing time. The second paragraph would “support” this lead with detail. It would name the arrested chef, identify the hotel and its address, elaborate on the charges and, perhaps, say exactly when the robbery took place and how. (It would not immediately name the desk clerk; too many specifics at once clutter the story.)

Wire service stories use a standard structure in building their stories. First comes the lead sentence. Then comes a sentence or two of lead support. Then comes a lead quote — spoken words that reinforce the story’s direction, emphasize the main theme and add color. During this class students should practice writing the lead through the lead quote on deadline. They should then read assignments aloud for critique by classmates and the professor.

Assignment: Using a fact pattern assigned by the instructor or taken from a text, students should write a story from the lead through the lead quote. They should determine whether the story needs context to support the lead and, if so, include it.

Class 2: When context matters

Sometimes a story’s importance rests on what came before. If one fancy restaurant closes its doors in the face of the faltering economy, it may warrant a few paragraphs mention. If it’s the fourth restaurant to close on the same block in the last two weeks, that’s likely front-page news. If two other restaurants closed last year, that might be worth noting in the story’s last sentence. It is far less important. Patterns provide context and, when significant, generally are mentioned either as part of the lead or in the support paragraph that immediately follows. This class will look at the difference between context — information needed near the top of a story to establish its significance as part of a broader pattern, and background — information that gives historical perspective but doesn’t define the news at hand.

Assignment: The course to this point has focused on writing the news. But reporters, of course, usually can’t write until they’ve reported. This typically starts with background research to establish what has come before, what hasn’t been covered well and who speaks with authority on an issue. Using databases such as Lexis/Nexis, students should background or read specific articles about an issue in science or policy that either is highlighted in the Policy Areas section of Journalist’s Resource website or is currently being researched on your campus. They should engage in this assignment knowing that a new development on the topic will be brought to light when they arrive at the next class.

Week 7: The reporter at work

Class 1: Research

Discuss the homework assignment. Where do reporters look to background an issue? How do they find documents, sources and resources that enable them to gather good information or identify key people who can help provide it? After the discussion, students should be given a study from the Policy Areas section of Journalist’s Resource website related to the subject they’ve been asked to explore.

The instructor should use this study to evaluate the nature structure of government/scientific reports. After giving students 15 minutes to scan the report, ask students to identify its most newsworthy point. Discuss what context might be needed to write a story about the study or report. Discuss what concepts or language students are having difficulty understanding.

Reading: Clark, Scanlan, pages 305-313, and relevant pages of the course text

Assignment: Students should (a) write a lead for a story based exclusively on the report (b) do additional background work related to the study in preparation for writing a full story on deadline. (c) translate at least one term used in the study that is not familiar to a lay audience.

Class 2: Writing the basic story on deadline

This class should begin with a discussion of the challenges of translating jargon and the importance of such translation in news reporting. Reporters translate by substituting a simple definition or, generally with the help of experts, comparing the unfamiliar to the familiar through use of analogy.

The remainder of the class should be devoted to writing a 15- to 20-line news report, based on the study, background research and, if one is available, a press release.

Reading: Pages 1-47 of Stein/Paterno, and relevant pages of the course text

Assignment: Prepare a list of questions that you would ask either the lead author of the study you wrote about on deadline or an expert who might offer an outside perspective.

Week 8: Effective interviewing

Class 1: Preparing and getting the interview

Successful interviews build from strong preparation. Reporters need to identify the right interview subjects, know what they’ve said before, interview them in a setting that makes them comfortable and ask questions that elicit interesting answers. Each step requires thought.

The professor should begin this class by critiquing some of the questions students drew up for homework. Are they open-ended or close-ended? Do they push beyond the obvious? Do they seek specific examples that explain the importance of the research or its applications? Do they probe the study’s potential weaknesses? Do they explore what directions the researcher might take next?

Discuss the readings and what steps reporters can take to background for an interview, track down a subject and prepare and rehearse questions in advance.

Reading: Stein/Paterno, pages 47-146, and relevant pages of the course text

Assignment: Students should prepare to interview their professor about his or her approach to and philosophy of teaching. Before crafting their questions, the students should background the instructor’s syllabi, public course evaluations and any pertinent writings.

Class 2: The interview and its aftermath

The interview, says Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Jacqui Banaszynski, is a dance which the reporter leads but does so to music the interview subject chooses. Though reporters prepare and rehearse their interviews, they should never read the questions they’ve considered in advance and always be prepared to change directions. To hear the subject’s music, reporters must be more focused on the answers than their next question. Good listeners make good interviewers — good listeners, that is, who don’t forget that it is also their responsibility to also lead.

Divide the class. As a team, five students should interview the professor about his/her approach to teaching. Each of these five should build on the focus and question of the previous questioner. The rest of the class should critique the questions, their clarity and their focus. Are the questioners listening? Are they maintaining control? Are they following up? The class also should discuss the reading, paying particularly close attention to the dynamics of an interview, the pace of questions, the nature of questions, its close and the reporter’s responsibility once an interview ends.

Assignment: Students should be assigned to small groups and asked to critique the news stories classmates wrote on deadline during the previous class.

Week 9: Building the story

Class 1: Critiquing the story

The instructor should separate students into groups of two or three and tell them to read their news stories to one another aloud. After each reading, the listeners should discuss what they liked and struggled with as the story audience. The reader in each case should reflect on what he or she learned from the process of reading the story aloud.

The instructor then should distribute one or two of the class stories that provide good and bad examples of story structure, information selection, content, organization and writing. These should be critiqued as a class.

Assignment: Students, working in teams, should develop an angle for a news follow to the study or report they covered on deadline. Each team should write a focus statement for the story it is proposing.

Class 2: Following the news

The instructor should lead a discussion about how reporters “enterprise,” or find original angles or approaches, by looking to the corners of news, identifying patterns of news, establishing who is affected by news, investigating the “why” of news, and examining what comes next.

Students should be asked to discuss the ideas they’ve developed to follow the news story. These can be assigned as longer-term team final projects for the semester. As part of this discussion, the instructor can help students map their next steps.

Reading: Wickham, Chapters 1-4 and 7, and relevant pages of the course text

Assignment: Students should find a news report that uses data to support or develop its main point. They should consider what and how much data is used, whether it is clear, whether it’s cluttered and whether it answers their questions. They should bring the article and a brief memo analyzing it to class.

Week 10: Making sense of data and statistics

Class 1: Basic math and the journalist’s job

Many reporters don’t like math. But in their jobs, it is everywhere. Reporters must interpret political polls, calculate percentage change in everything from property taxes to real estate values, make sense of municipal bids and municipal budgets, and divine data in government reports.

First discuss some of the examples of good and bad use of data that students found in their homework. Then, using examples from Journalist’s Resource website, discuss good and poor use of data in news reporting. (Reporters, for example, should not overwhelm readers with paragraphs stuffed with statistics.) Finally lead students through some of the basic skills sets outlined in Wickham’s book, using her exercises to practice everything from calculating percentage change to interpreting polls.

Assignment: Give students a report or study linked to the Journalist’s Resource website that requires some degree of statistical evaluation or interpretation. Have students read the report and compile a list of questions they would ask to help them understand and interpret this data.

Class 2: The use and abuse of statistics

Discuss the students’ questions. Then evaluate one or more articles drawn from the report they’ve analyzed that attempt to make sense of the data in the study. Discuss what these articles do well and what they do poorly.

Reading: Zinsser, Chapter 13, “Macabre Reminder: The Corpse on Union Street,” Dan Barry, The New York Times

Week 11: The reporter as observer

Class 1: Using the senses

Veteran reporters covering an event don’t only return with facts, quotes and documents that support them. They fill their notebooks with details that capture what they’ve witnessed. They use all their senses, listening for telling snippets of conversation and dialogue, watching for images, details and actions that help bring readers to the scene. Details that develop character and place breathe vitality into news. But description for description’s sake merely clutters and obscures the news. Using the senses takes practice.

The class should deconstruct “Macabre Reminder: The Corpse on Union Street,” a remarkable journey around New Orleans a few days after Hurricane Katrina devastated the city in 2005. The story starts with one corpse, left to rot on a once-busy street and then pans the city as a camera might. The dead body serves as a metaphor for the rotting city, largely abandoned and without order.

Assignment: This is an exercise in observation. Students may not ask questions. Their task is to observe, listen and describe a short scene, a serendipitous vignette of day-to-day life. They should take up a perch in a lively location of their choosing — a student dining hall or gym, a street corner, a pool hall or bus stop or beauty salon, to name a few — wait and watch. When a small scene unfolds, one with beginning, middle and end, students should record it. They then should write a brief story describing the scene that unfolded, taking care to leave themselves and their opinions out of the story. This is pure observation, designed to build the tools of observation and description. These stories should be no longer than 200 words.

Class 2: Sharpening the story

Students should read their observation pieces aloud to a classmate. Both students should consider these questions: Do the words describe or characterize? Which words show and which words tell? What words are extraneous? Does the piece convey character through action? Does it have a clear beginning, middle and end? Students then should revise, shortening the original scene to no longer than 150 words. After the revision, the instructor should critique some of the students’ efforts.

Assignment: Using campus, governmental or media calendars, students should identify, background and prepare to cover a speech, press conference or other news event, preferably on a topic related to one of the research-based areas covered in the Policy Areas section of Journalist’s Resource website. Students should write a focus statement (50 words or less) for their story and draw up a list of some of the questions they intend to ask.

Week 12: Reporting on deadline

Class 1: Coaching the story

Meetings, press conferences and speeches serve as a staple for much news reporting. Reporters should arrive at such events knowledgeable about the key players, their past positions or research, and the issues these sources are likely discuss. Reporters can discover this information in various ways. They can research topic and speaker online and in journalistic databases, peruse past correspondence sent to public offices, and review the writings and statements of key speakers with the help of their assistants or secretaries.

In this class, the instructor should discuss the nature of event coverage, review students’ focus statements and questions, and offer suggestions about how they cover the events.

Assignment: Cover the event proposed in the class above and draft a 600-word story, double-spaced, based on its news and any context needed to understand it.

Class 2: Critiquing and revising the story

Students should exchange story drafts and suggest changes. After students revise, the instructor should lead a discussion about the challenges of reporting and writing live on deadline. These likely will include issues of access and understanding and challenges of writing around and through gaps of information.

Weeks 13/14: Coaching the final project

Previous week | Back to top

The final week or two of the class is reserved for drill in areas needing further development and for coaching students through the final reporting, drafting and revision of the enterprise stories off the study or report they covered in class.

Tags: training

About The Author

The Journalist's Resource

The Assignment with Audie Cornish

Every thursday on the assignment, host audie cornish explores the animating forces of this extraordinary american political moment. it’s not about the horse race, it’s about the larger cultural ideas driving the conversation: the role of online influencers on the electorate, the intersection of pop culture and politics, and discussions with primary voices and thinkers who are shaping the political conversation..

- Apple Podcasts

Watch CBS News

Hate Rising: White Supremacy in America

Advertisement

Supported by

On Assignment Inc.

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply —use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important