- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to present patient...

How to present patient cases

- Related content

- Peer review

- Mary Ni Lochlainn , foundation year 2 doctor 1 ,

- Ibrahim Balogun , healthcare of older people/stroke medicine consultant 1

- 1 East Kent Foundation Trust, UK

A guide on how to structure a case presentation

This article contains...

-History of presenting problem

-Medical and surgical history

-Drugs, including allergies to drugs

-Family history

-Social history

-Review of systems

-Findings on examination, including vital signs and observations

-Differential diagnosis/impression

-Investigations

-Management

Presenting patient cases is a key part of everyday clinical practice. A well delivered presentation has the potential to facilitate patient care and improve efficiency on ward rounds, as well as a means of teaching and assessing clinical competence. 1

The purpose of a case presentation is to communicate your diagnostic reasoning to the listener, so that he or she has a clear picture of the patient’s condition and further management can be planned accordingly. 2 To give a high quality presentation you need to take a thorough history. Consultants make decisions about patient care based on information presented to them by junior members of the team, so the importance of accurately presenting your patient cannot be overemphasised.

As a medical student, you are likely to be asked to present in numerous settings. A formal case presentation may take place at a teaching session or even at a conference or scientific meeting. These presentations are usually thorough and have an accompanying PowerPoint presentation or poster. More often, case presentations take place on the wards or over the phone and tend to be brief, using only memory or short, handwritten notes as an aid.

Everyone has their own presenting style, and the context of the presentation will determine how much detail you need to put in. You should anticipate what information your senior colleagues will need to know about the patient’s history and the care he or she has received since admission, to enable them to make further management decisions. In this article, I use a fictitious case to show how you can structure case presentations, which can be adapted to different clinical and teaching settings (box 1).

Box 1: Structure for presenting patient cases

Presenting problem, history of presenting problem, medical and surgical history.

Drugs, including allergies to drugs

Family history

Social history, review of systems.

Findings on examination, including vital signs and observations

Differential diagnosis/impression

Investigations

Case: tom murphy.

You should start with a sentence that includes the patient’s name, sex (Mr/Ms), age, and presenting symptoms. In your presentation, you may want to include the patient’s main diagnosis if known—for example, “admitted with shortness of breath on a background of COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease].” You should include any additional information that might give the presentation of symptoms further context, such as the patient’s profession, ethnic origin, recent travel, or chronic conditions.

“ Mr Tom Murphy is a 56 year old ex-smoker admitted with sudden onset central crushing chest pain that radiated down his left arm.”

In this section you should expand on the presenting problem. Use the SOCRATES mnemonic to help describe the pain (see box 2). If the patient has multiple problems, describe each in turn, covering one system at a time.

Box 2: SOCRATES—mnemonic for pain

Associations

Time course

Exacerbating/relieving factors

“ The pain started suddenly at 1 pm, when Mr Murphy was at his desk. The pain was dull in nature, and radiated down his left arm. He experienced shortness of breath and felt sweaty and clammy. His colleague phoned an ambulance. He rated the pain 9/10 in severity. In the ambulance he was given GTN [glyceryl trinitrate] spray under the tongue, which relieved the pain to 5/10. The pain lasted 30 minutes in total. No exacerbating factors were noted. Of note: Mr Murphy is an ex-smoker with a 20 pack year history”

Some patients have multiple comorbidities, and the most life threatening conditions should be mentioned first. They can also be categorised by organ system—for example, “has a long history of cardiovascular disease, having had a stroke, two TIAs [transient ischaemic attacks], and previous ACS [acute coronary syndrome].” For some conditions it can be worth stating whether a general practitioner or a specialist manages it, as this gives an indication of its severity.

In a surgical case, colleagues will be interested in exercise tolerance and any comorbidity that could affect the patient’s fitness for surgery and anaesthesia. If the patient has had any previous surgical procedures, mention whether there were any complications or reactions to anaesthesia.

“Mr Murphy has a history of type 2 diabetes, well controlled on metformin. He also has hypertension, managed with ramipril, and gout. Of note: he has no history of ischaemic heart disease (relevant negative) (see box 3).”

Box 3: Relevant negatives

Mention any relevant negatives that will help narrow down the differential diagnosis or could be important in the management of the patient, 3 such as any risk factors you know for the condition and any associations that you are aware of. For example, if the differential diagnosis includes a condition that you know can be hereditary, a relevant negative could be the lack of a family history. If the differential diagnosis includes cardiovascular disease, mention the cardiovascular risk factors such as body mass index, smoking, and high cholesterol.

Highlight any recent changes to the patient’s drugs because these could be a factor in the presenting problem. Mention any allergies to drugs or the patient’s non-compliance to a previously prescribed drug regimen.

To link the medical history and the drugs you might comment on them together, either here or in the medical history. “Mrs Walsh’s drugs include regular azathioprine for her rheumatoid arthritis.”Or, “His regular drugs are ramipril 5 mg once a day, metformin 1g three times a day, and allopurinol 200 mg once a day. He has no known drug allergies.”

If the family history is unrelated to the presenting problem, it is sufficient to say “no relevant family history noted.” For hereditary conditions more detail is needed.

“ Mr Murphy’s father experienced a fatal myocardial infarction aged 50.”

Social history should include the patient’s occupation; their smoking, alcohol, and illicit drug status; who they live with; their relationship status; and their sexual history, baseline mobility, and travel history. In an older patient, more detail is usually required, including whether or not they have carers, how often the carers help, and if they need to use walking aids.

“He works as an accountant and is an ex-smoker since five years ago with a 20 pack year history. He drinks about 14 units of alcohol a week. He denies any illicit drug use. He lives with his wife in a two storey house and is independent in all activities of daily living.”

Do not dwell on this section. If something comes up that is relevant to the presenting problem, it should be mentioned in the history of the presenting problem rather than here.

“Systems review showed long standing occasional lower back pain, responsive to paracetamol.”

Findings on examination

Initially, it can be useful to practise presenting the full examination to make sure you don’t leave anything out, but it is rare that you would need to present all the normal findings. Instead, focus on the most important main findings and any abnormalities.

“On examination the patient was comfortable at rest, heart sounds one and two were heard with no additional murmurs, heaves, or thrills. Jugular venous pressure was not raised. No peripheral oedema was noted and calves were soft and non-tender. Chest was clear on auscultation. Abdomen was soft and non-tender and normal bowel sounds were heard. GCS [Glasgow coma scale] was 15, pupils were equal and reactive to light [PEARL], cranial nerves 1-12 were intact, and he was moving all four limbs. Observations showed an early warning score of 1 for a tachycardia of 105 beats/ min. Blood pressure was 150/90 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 breaths/min, saturations were 98% on room air, and he was apyrexial with a temperature of 36.8 ºC.”

Differential diagnoses

Mentioning one or two of the most likely diagnoses is sufficient. A useful phrase you can use is, “I would like to rule out,” especially when you suspect a more serious cause is in the differential diagnosis. “History and examination were in keeping with diverticular disease; however, I would like to rule out colorectal cancer in this patient.”

Remember common things are common, so try not to mention rare conditions first. Sometimes it is acceptable to report investigations you would do first, and then base your differential diagnosis on what the history and investigation findings tell you.

“My impression is acute coronary syndrome. The differential diagnosis includes other cardiovascular causes such as acute pericarditis, myocarditis, aortic stenosis, aortic dissection, and pulmonary embolism. Possible respiratory causes include pneumonia or pneumothorax. Gastrointestinal causes include oesophageal spasm, oesophagitis, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, gastritis, cholecystitis, and acute pancreatitis. I would also consider a musculoskeletal cause for the pain.”

This section can include a summary of the investigations already performed and further investigations that you would like to request. “On the basis of these differentials, I would like to carry out the following investigations: 12 lead electrocardiography and blood tests, including full blood count, urea and electrolytes, clotting screen, troponin levels, lipid profile, and glycated haemoglobin levels. I would also book a chest radiograph and check the patient’s point of care blood glucose level.”

You should consider recommending investigations in a structured way, prioritising them by how long they take to perform and how easy it is to get them done and how long it takes for the results to come back. Put the quickest and easiest first: so bedside tests, electrocardiography, followed by blood tests, plain radiology, then special tests. You should always be able to explain why you would like to request a test. Mention the patient’s baseline test values if they are available, especially if the patient has a chronic condition—for example, give the patient’s creatinine levels if he or she has chronic kidney disease This shows the change over time and indicates the severity of the patient’s current condition.

“To further investigate these differentials, 12 lead electrocardiography was carried out, which showed ST segment depression in the anterior leads. Results of laboratory tests showed an initial troponin level of 85 µg/L, which increased to 1250 µg/L when repeated at six hours. Blood test results showed raised total cholesterol at 7.6 mmol /L and nil else. A chest radiograph showed clear lung fields. Blood glucose level was 6.3 mmol/L; a glycated haemoglobin test result is pending.”

Dependent on the case, you may need to describe the management plan so far or what further management you would recommend.“My management plan for this patient includes ACS [acute coronary syndrome] protocol, echocardiography, cardiology review, and treatment with high dose statins. If you are unsure what the management should be, you should say that you would discuss further with senior colleagues and the patient. At this point, check to see if there is a treatment escalation plan or a “do not attempt to resuscitate” order in place.

“Mr Murphy was given ACS protocol in the emergency department. An echocardiogram has been requested and he has been discussed with cardiology, who are going to come and see him. He has also been started on atorvastatin 80 mg nightly. Mr Murphy and his family are happy with this plan.”

The summary can be a concise recap of what you have presented beforehand or it can sometimes form a standalone presentation. Pick out salient points, such as positive findings—but also draw conclusions from what you highlight. Finish with a brief synopsis of the current situation (“currently pain free”) and next step (“awaiting cardiology review”). Do not trail off at the end, and state the diagnosis if you are confident you know what it is. If you are not sure what the diagnosis is then communicate this uncertainty and do not pretend to be more confident than you are. When possible, you should include the patient’s thoughts about the diagnosis, how they are feeling generally, and if they are happy with the management plan.

“In summary, Mr Murphy is a 56 year old man admitted with central crushing chest pain, radiating down his left arm, of 30 minutes’ duration. His cardiac risk factors include 20 pack year smoking history, positive family history, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension. Examination was normal other than tachycardia. However, 12 lead electrocardiography showed ST segment depression in the anterior leads and troponin rise from 85 to 250 µg/L. Acute coronary syndrome protocol was initiated and a diagnosis of NSTEMI [non-ST elevation myocardial infarction] was made. Mr Murphy is currently pain free and awaiting cardiology review.”

Originally published as: Student BMJ 2017;25:i4406

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

- ↵ Green EH, Durning SJ, DeCherrie L, Fagan MJ, Sharpe B, Hershman W. Expectations for oral case presentations for clinical clerks: opinions of internal medicine clerkship directors. J Gen Intern Med 2009 ; 24 : 370 - 3 . doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0900-x pmid:19139965 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Olaitan A, Okunade O, Corne J. How to present clinical cases. Student BMJ 2010;18:c1539.

- ↵ Gaillard F. The secret art of relevant negatives, Radiopedia 2016; http://radiopaedia.org/blog/the-secret-art-of-relevant-negatives .

How to make an oral case presentation to healthcare colleagues

The content and delivery of a patient case for education and evidence-based care discussions in clinical practice.

BSIP SA / Alamy Stock Photo

A case presentation is a detailed narrative describing a specific problem experienced by one or more patients. Pharmacists usually focus on the medicines aspect , for example, where there is potential harm to a patient or proven benefit to the patient from medication, or where a medication error has occurred. Case presentations can be used as a pedagogical tool, as a method of appraising the presenter’s knowledge and as an opportunity for presenters to reflect on their clinical practice [1] .

The aim of an oral presentation is to disseminate information about a patient for the purpose of education, to update other members of the healthcare team on a patient’s progress, and to ensure the best, evidence-based care is being considered for their management.

Within a hospital, pharmacists are likely to present patients on a teaching or daily ward round or to a senior pharmacist or colleague for the purpose of asking advice on, for example, treatment options or complex drug-drug interactions, or for referral.

Content of a case presentation

As a general structure, an oral case presentation may be divided into three phases [2] :

- Reporting important patient information and clinical data;

- Analysing and synthesising identified issues (this is likely to include producing a list of these issues, generally termed a problem list);

- Managing the case by developing a therapeutic plan.

Specifically, the following information should be included [3] :

Patient and complaint details

Patient details: name, sex, age, ethnicity.

Presenting complaint: the reason the patient presented to the hospital (symptom/event).

History of presenting complaint: highlighting relevant events in chronological order, often presented as how many days ago they occurred. This should include prior admission to hospital for the same complaint.

Review of organ systems: listing positive or negative findings found from the doctor’s assessment that are relevant to the presenting complaint.

Past medical and surgical history

Social history: including occupation, exposures, smoking and alcohol history, and any recreational drug use.

Medication history, including any drug allergies: this should include any prescribed medicines, medicines purchased over-the-counter, any topical preparations used (including eye drops, nose drops, inhalers and nasal sprays) and any herbal or traditional remedies taken.

Sexual history: if this is relevant to the presenting complaint.

Details from a physical examination: this includes any relevant findings to the presenting complaint and should include relevant observations.

Laboratory investigation and imaging results: abnormal findings are presented.

Assessment: including differential diagnosis.

Plan: including any pharmaceutical care issues raised and how these should be resolved, ongoing management and discharge planning.

Any discrepancies between the current management of the patient’s conditions and evidence-based recommendations should be highlighted and reasons given for not adhering to evidence-based medicine ( see ‘Locating the evidence’ ).

Locating the evidence

The evidence base for the therapeutic options available should always be considered. There may be local guidance available within the hospital trust directing the management of the patient’s presenting condition. Pharmacists often contribute to the development of such guidelines, especially if medication is involved. If no local guidelines are available, the next step is to refer to national guidance. This is developed by a steering group of experts, for example, the British HIV Association or the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . If the presenting condition is unusual or rare, for example, acute porphyria, and there are no local or national guidelines available, a literature search may help locate articles or case studies similar to the case.

Giving a case presentation

Currently, there are no available acknowledged guidelines or systematic descriptions of the structure, language and function of the oral case presentation [4] and therefore there is no standard on how the skills required to prepare or present a case are taught. Most individuals are introduced to this concept at undergraduate level and then build on their skills through practice-based learning.

A case presentation is a narrative of a patient’s care, so it is vital the presenter has familiarity with the patient, the case and its progression. The preparation for the presentation will depend on what information is to be included.

Generally, oral case presentations are brief and should be limited to 5–10 minutes. This may be extended if the case is being presented as part of an assessment compared with routine everyday working ( see ‘Case-based discussion’ ). The audience should be interested in what is being said so the presenter should maintain this engagement through eye contact, clear speech and enthusiasm for the case.

It is important to stick to the facts by presenting the case as a factual timeline and not describing how things should have happened instead. Importantly, the case should always be concluded and should include an outcome of the patient’s care [5] .

An example of an oral case presentation, given by a pharmacist to a doctor, is available here .

A successful oral case presentation allows the audience to garner the right amount of patient information in the most efficient way, enabling a clinically appropriate plan to be developed. The challenge lies with the fact that the content and delivery of this will vary depending on the service, and clinical and audience setting [3] . A practitioner with less experience may find understanding the balance between sufficient information and efficiency of communication difficult, but regular use of the oral case presentation tool will improve this skill.

Tailoring case presentations to your audience

Most case presentations are not tailored to a specific audience because the same type of information will usually need to be conveyed in each case.

However, case presentations can be adapted to meet the identified learning needs of the target audience, if required for training purposes. This method involves varying the content of the presentation or choosing specific cases to present that will help achieve a set of objectives [6] . For example, if a requirement to learn about the management of acute myocardial infarction has been identified by the target audience, then the presenter may identify a case from the cardiology ward to present to the group, as opposed to presenting a patient reviewed by that person during their normal working practice.

Alternatively, a presenter could focus on a particular condition within a case, which will dictate what information is included. For example, if a case on asthma is being presented, the focus may be on recent use of bronchodilator therapy, respiratory function tests (including peak expiratory flow rate), symptoms related to exacerbation of airways disease, anxiety levels, ability to talk in full sentences, triggers to worsening of symptoms, and recent exposure to allergens. These may not be considered relevant if presenting the case on an unrelated condition that the same patient has, for example, if this patient was admitted with a hip fracture and their asthma was well controlled.

Case-based discussion

The oral case presentation may also act as the basis of workplace-based assessment in the form of a case-based discussion. In the UK, this forms part of many healthcare professional bodies’ assessment of clinical practice, for example, medical professional colleges.

For pharmacists, a case-based discussion forms part of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) Foundation and Advanced Practice assessments . Mastery of the oral case presentation skill could provide useful preparation for this assessment process.

A case-based discussion would include a pharmaceutical needs assessment, which involves identifying and prioritising pharmaceutical problems for a particular patient. Evidence-based guidelines relevant to the specific medical condition should be used to make treatment recommendations, and a plan to monitor the patient once therapy has started should be developed. Professionalism is an important aspect of case-based discussion — issues must be prioritised appropriately and ethical and legal frameworks must be referred to [7] . A case-based discussion would include broadly similar content to the oral case presentation, but would involve further questioning of the presenter by the assessor to determine the extent of the presenter’s knowledge of the specific case, condition and therapeutic strategies. The criteria used for assessment would depend on the level of practice of the presenter but, for pharmacists, this may include assessment against the RPS Foundation or Pharmacy Frameworks .

Acknowledgement

With thanks to Aamer Safdar for providing the script for the audio case presentation.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal . You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

[1] Onishi H. The role of case presentation for teaching and learning activities. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2008;24:356–360. doi: 10.1016/s1607-551x(08)70132–3

[2] Edwards JC, Brannan JR, Burgess L et al . Case presentation format and clinical reasoning: a strategy for teaching medical students. Medical Teacher 1987;9:285–292. doi: 10.3109/01421598709034790

[3] Goldberg C. A practical guide to clinical medicine: overview and general information about oral presentation. 2009. University of California, San Diego. Available from: https://meded.ecsd.edu/clinicalmed.oral.htm (accessed 5 December 2015)

[4] Chan MY. The oral case presentation: toward a performance-based rhetorical model for teaching and learning. Medical Education Online 2015;20. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.28565

[5] McGee S. Medicine student programs: oral presentation guidelines. Learning & Scholarly Technologies, University of Washington. Available from: https://catalyst.uw.edu/workspace/medsp/30311/202905 (accessed 7 December 2015)

[6] Hays R. Teaching and Learning in Clinical Settings. 2006;425. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd.

[7] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Tips for assessors for completing case-based discussions. 2015. Available from: http://www.rpharms.com/help/case_based_discussion.htm (accessed 30 December 2015)

You might also be interested in…

Health psychology and advanced communication skills for prescribers

How to demonstrate empathy and compassion in a pharmacy setting

Be more proactive to convince medics, pharmacists urged

The Ultimate Patient Case Presentation Template for Med Students

- April 6, 2024

- Reviewed by: Amy Rontal, MD

Knowing how to deliver a patient presentation is one of the most important skills to learn on your journey to becoming a physician. After all, when you’re on a medical team, you’ll need to convey all the critical information about a patient in an organized manner without any gaps in knowledge transfer.

One big caveat: opinions about the correct way to present a patient are highly personal and everyone is slightly different. Additionally, there’s a lot of variation in presentations across specialties, and even for ICU vs floor patients.

My goal with this blog is to give you the most complete version of a patient presentation, so you can tailor your presentations to the preferences of your attending and team. So, think of what follows as a model for presenting any general patient.

Here’s a breakdown of what goes into the typical patient presentation.

Looking for some help studying your shelf/Step 2 studying with clinical rotations? Try our combined Step 2 & Shelf Exams Qbank with 5,500 practice questions— free for 7 days!

7 Ingredients for a Patient Case Presentation Template

1. the one-liner.

The one-liner is a succinct sentence that primes your listeners to the patient.

A typical format is: “[Patient name] is a [age] year-old [gender] with past medical history of [X] presenting with [Y].

2. The Chief Complaint

This is a very brief statement of the patient’s complaint in their own words. A common pitfall is when medical students say that the patient had a chief complaint of some medical condition (like cholecystitis) and the attending asks if the patient really used that word!

An example might be, “Patient has chief complaint of difficulty breathing while walking.”

3. History of Present Illness (HPI)

The goal of the HPI is to illustrate the story of the patient’s complaint. I remember when I first began medical school, I had a lot of trouble determining what was relevant and ended up giving a lot of extra details. Don’t worry if you have the same issue. With time, you’ll learn which details are important.

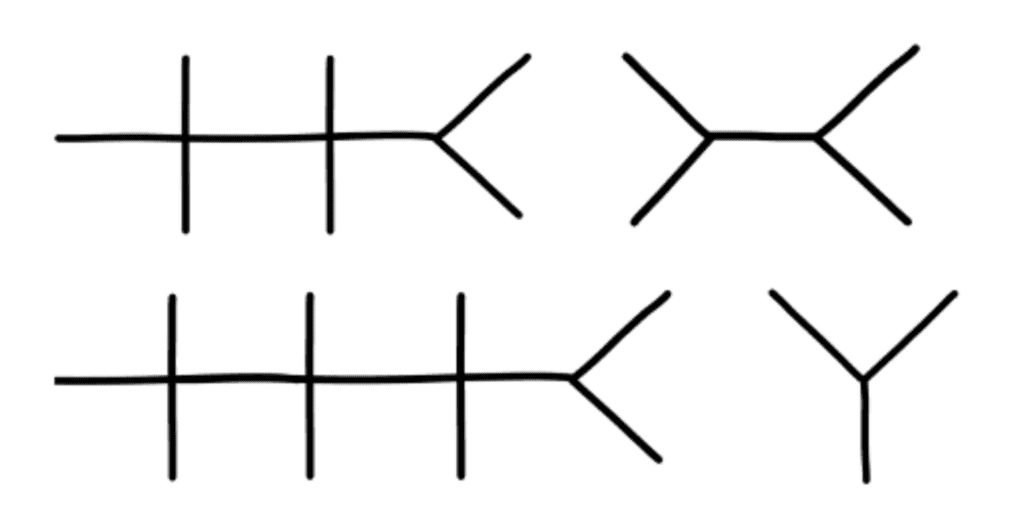

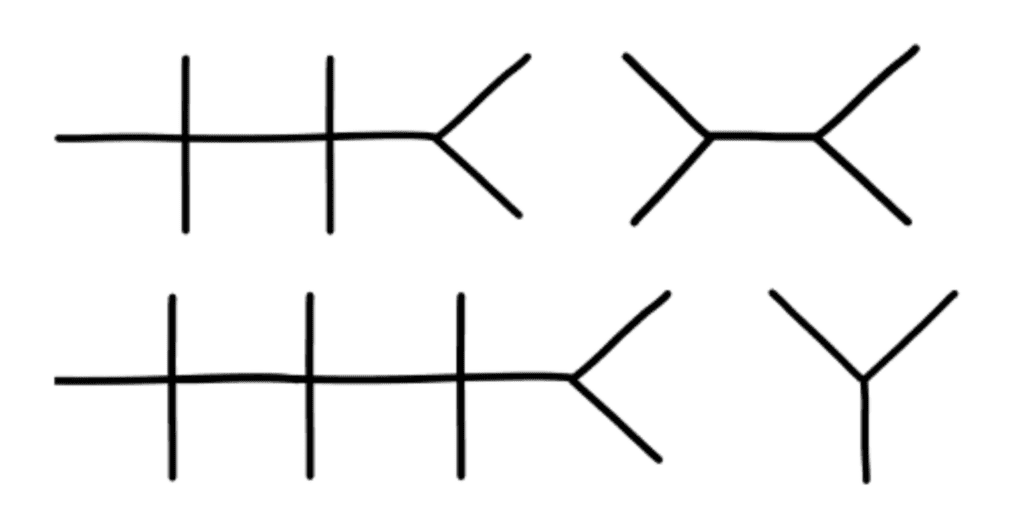

The OPQRST Framework

In the beginning of your clinical experience, a helpful framework to use is OPQRST:

Describe when the issue started, and if it occurs during certain environmental or personal exposures.

P rovocative

Report if there are any factors that make the pain better or worse. These can be broad, like noting their shortness of breath worsened when lying flat, or their symptoms resolved during rest.

Relay how the patient describes their pain or associated symptoms. For example, does the patient have a burning versus a pressure sensation? Are they feeling weakness, stiffness, or pain?

R egion/Location

Indicate where the pain is located and if it radiates anywhere.

Talk about how bad the pain is for the patient. Typically, a 0-10 pain scale is useful to provide some objective measure.

Discuss how long the pain lasts and how often it occurs.

A Case Study

While the OPQRST framework is great when starting out, it can be limiting. Let’s take an example where the patient is not experiencing pain and comes in with altered mental status along with diffuse jaundice of the skin and a history of chronic liver disease. You will find that certain sections of OPQRST do not apply.

In this event, the HPI is still a story, but with a different framework. Try to go in chronological order. Include relevant details like if there have been any changes in medications, diet, or bowel movements.

Pertinent Positive and Negative Symptoms

Regardless of the framework you use, the name of the game is pertinent positive and negative symptoms the patient is experiencing. I’d like to highlight the word “pertinent.” It’s less likely the patient’s chronic osteoarthritis and its management is related to their new onset shortness of breath, but it’s still important for knowing the patient’s complete medical picture. A better place to mention these details would be in the “Past Medical History” section, and reserve the HPI portion for more pertinent history.

As you become exposed to more illness scripts, experience will teach you which parts of the history are most helpful to state. Also, as you spend more time on the wards, you will pick up on which questions are relevant and important to ask during the patient interview. By painting a clear picture with pertinent positives and negatives during your presentation, the history will guide what may be higher or lower on the differential diagnosis.

Some other important components to add are the patient’s additional past medical/surgical history, family history, social history, medications, allergies, and immunizations.

The HEADSSS Method

Particularly, the social history is an important time to describe the patient as a complete person and understand how their life story may affect their present condition.

One way of organizing the social history is the HEADSSS method: – H ome living situation and relationships – E ducation and employment – A ctivities and hobbies – D rug use (alcohol, tobacco, cocaine, etc.) Note frequency of use, and if applicable, be sure to add which types of alcohol consumption (like beer versus hard liquor) and forms of drug use. – S exual history (partners, STI history, pregnancy plans) – S uicidality and depression – S piritual and religious history Again, there’s a lot of variation in presenting social history, so just follow the lead of your team. For example, it’s not always necessary/relevant to obtain a sexual history, so use your judgment of the situation.

4. Review of Symptoms

Oftentimes, most elements of this section are embedded within the HPI. If there are any additional symptoms not mentioned in the HPI, it’s appropriate to state them here.

5. Objective

Vital signs.

Some attendings love to hear all five vital signs: temperature, blood pressure (mean arterial pressure if applicable), heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation. Others are happy with “afebrile and vital signs stable.” Just find out their preference and stick to that.

Physical Exam

This is one of the most important parts of the patient presentation for any specialty. It paints a picture of how the patient looks and can guide acute management like in the case of a rigid abdomen. As discussed in the HPI section, typically you should report pertinent positives and negatives.

When you’re starting out, your attending and team may prefer for you to report all findings as part of your learning. For example, pulmonary exam findings can be reported as: “Regular chest appearance. No abnormalities on palpation. Lungs resonant to percussion. Clear to auscultation bilaterally without crackles, rhonchi, or wheezing.”

Typically, you want to report the physical exams in a head to toe format: General Appearance, Mental Status, Neurologic, Eyes/Ears/Nose/Mouth/Neck, Cardiovascular, Pulmonary, Breast, Abdominal, Genitourinary, Musculoskeletal, and Skin. Depending on the situation, additional exams can be incorporated as applicable.

Now comes reporting pertinent positive and negative labs. Several labs are often drawn upon admission. It’s easy to fall into the trap of reading off all the labs and losing everyone’s attention. Here are some pieces of advice:

You normally can’t go wrong sticking to abnormal lab values.

One qualification is that for a patient with concern for acute coronary syndrome, reporting a normal troponin is essential. Also, stating the normalization of previously abnormal lab values like liver enzymes is important.

Demonstrate trends in lab values.

A lab value is just a single point in time and does not paint the full picture. For example, a hemoglobin of 10g/dL in a patient at 15g/dL the previous day is a lot more concerning than a patient who has been stable at 10g/dL for a week.

Try to avoid editorializing in this section.

Save your analysis of the labs for the assessment section. Again, this can be a point of personal preference. In my experience, the team typically wants the raw objective data in this section.

This is also a good place to state the ins and outs of your patient (if applicable). In some patients, these metrics are strictly recorded and are typically reported as total fluid in and out over the past day followed by the net fluid balance. For example, “1L in, 2L out, net -1L over the past 24 hours.”

6. Diagnostics/Imaging

Next, you’ll want to review any important diagnostic tests and imaging. For example, describe how the EKG and echo look in a patient presenting with chest pain or the abdominal CT scan in a patient with right lower quadrant abdominal pain.

Try to provide your own interpretation to develop your skills and then include the final impression. Also, report if a diagnostic test is still pending.

7. Assessment/Plan

This is the fun part where you get to use your critical thinking (aka doctor) skills! For the scope of this blog, we’ll review a problem-based plan. It’s helpful to begin with a summary statement that incorporates the one-liner, presenting issue(s)/diagnosis(es), and patient stability.

Then, go through all the problems relevant to the admission. You can impress your audience by casting a wide differential diagnosis and going through the elements of your patient presentation that support one diagnosis over another. Following your assessment, try to suggest a management plan. In a patient with congestive heart failure exacerbation, initiating a diuresis regimen and measuring strict ins/outs are good starting points.

You may even suggest a follow-up on their latest ejection fraction with an echo and check if they’re on guideline-directed medical therapy. Again, with more time on the clinical wards you’ll start to pick up on what management plan to suggest.

One pointer is to talk about all relevant problems, not just the presenting issue. For example, a patient with diabetes may need to be put on a sliding scale insulin regimen or another patient may require physical/occupational therapy. Just try to stay organized and be comprehensive.

A Note About Patient Presentation Skills

When you’re doing your first patient presentations, it’s common to feel nervous. There may be a lot of “uhs” and “ums.”

Here’s the good news: you don’t have to be perfect! You just need to make a good faith attempt and keep on going with the presentation.

With time, your confidence will build. Practice your fluency in the mirror when you have a chance. No one was born knowing medicine and everyone has gone through the same stages of learning you are!

Practice your presentation a couple times before you present to the team if you have time. Pull a resident aside if they have the bandwidth to make sure you have all the information you need.

One big piece of advice: NEVER LIE. If you don’t know a specific detail, it’s okay to say, “I’m not sure, but I can look that up.” Someone on your team can usually retrieve the information while you continue on with your presentation.

Example Patient Case Presentation Template

Here’s a blank patient case presentation template that may come in handy. You can adapt it to best fit your needs.

One-Liner:

Chief Complaint:

History of Present Illness:

Past Medical History:

Past Surgical History:

Family History:

Social History:

Medications:

Immunizations:

Objective:

Vital Signs :

BP ___ /___

O2 sat ___

Physical Exam:

General Appearance:

Mental Status:

Neurological:

Eyes, Ears, Nose, Mouth, and Neck:

Cardiovascular:

Genitourinary:

Musculoskeletal:

Most Recent Labs:

Previous Labs:

Diagnostics/Imaging:

Impression/Interpretation:

Assessment/Plan:

One-line summary:

#Problem 1:

Assessment:

#Problem 2:

Final Thoughts on Patient Presentations

I hope this post demystified the patient presentation for you. Be sure to stay organized in your delivery and be flexible with the specifications your team may provide. Something I’d like to highlight is that you may need to tailor the presentation to the specialty you’re on. For example, on OB/GYN, it’s important to include a pregnancy history.

Nonetheless, the aforementioned template should set you up for success from a broad overview perspective. Stay tuned for my next post on how to give an ICU patient presentation. And if you’d like me to address any other topics in a blog, write to me at [email protected] !

Looking for more (free!) content to help you through clinical rotations? Check out these other posts from Blueprint tutors on the Med School blog:

- How I Balanced My Clinical Rotations with Shelf Exam Studying

- How (and Why) to Use a Qbank to Prepare for USMLE Step 2

- How to Study For Shelf Exams: A Tutor’s Guide

About the Author

Hailing from Phoenix, AZ, Neelesh is an enthusiastic, cheerful, and patient tutor. He is currently an Integrated Cardiothoracic Surgery Resident at The Ohio State University. He graduated from the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California and served as president for the Class of 2024. He also graduated as valedictorian of his high school and the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, obtaining a B.S. in Biomedical Engineering in 2020. He discovered his penchant for teaching when he began tutoring his friends for the SAT and ACT in the summer of 2015 out of his living room. Outside of the academic sphere, Neelesh enjoys surfing and camping. Twitter: @NeeleshBagrodia LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin. com/in/ neelesh -bagrodia

Related Posts

How to Study For Shelf Exams: A Tutor’s Guide

- May 6, 2024

The Ultimate ICU Patient Presentation Template for Med Students

- May 3, 2024

Quiz: Which “Scrubs” Character Are You in Your Clinical Rotations?

- March 26, 2024

- [email protected]

- +91 9884350006

- +1-972-502-9262

- Discovery & Intelligence Services

Publication Support Service

Journal Selection

Pre-Submission Peer Review

Journal Submission

Response To Reviewers

Poster Creation & Design

Formatting Service

Artwork Editing Service

Plagiarism service

Video Abstract

Editing and Translation Services

Scientific Editing

Manuscript Editing

Book Editing

Post Editing

Thesis Editing

Translation with Editing

Editing and Translation Service

Research Services

Medical Writing

Scientific Writing

Systematic Review

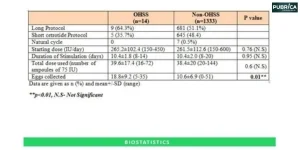

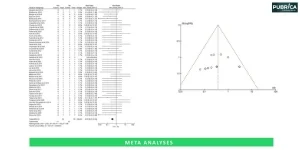

Meta Analysis

Original Research Article

Literature Review

Grant writing services

Biostatistical Programming

Experimental Design

Physician Writing Service

Case Report Writing

Patient Education Materials

Literature Search & Citation

Physician Manuscript

Physician Training

Clinical Literature Review

Customized Writing

Research Proposal

Patient Education Content

Statistical Analyses

Biostatistics

Meta-analyses

Bioinformatics

- Data Collection

AI & ML Solutions

Health Economics

Patient journey & Insights -ML

Segmentation

Predictive Anlaysis

Algorithm Development

Interpretation & Visualisation

AI and ML Services

Research Impact

Graphical Abstract

Poster Presentation

Scientific News Report

Simplified Abstract

Medical & Scientific Communication

Leadership Content

Marketing Communication

- Medico Legal Services

- Educational Content

- Our Quality

- Get in Touch

How should a case presentation be structured?

A case study presentation entails a thorough evaluation of a particular subject, which might be an individual, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. This study is painstakingly arranged and interactively presented to engage the audience actively. Unlike a standard report or whitepaper, the goal of a case study presentation is to encourage viewers to think critically.

Check our Examples to know more how we research/review/edit case report papers.

A case presentation is a structured way of communicating information about a patient to colleagues or supervisors. It is commonly used in medical and healthcare settings but can be adapted for other fields as well. Here is a general structure for a medical case report presentation:

- Introduction:

- Introduce yourself and your role.

- Provide a brief overview of the patient, including age, gender, and relevant background information.

- Chief Complaint (CC):

- State the reason the patient sought medical attention in their own words.

- Include the duration and any associated symptoms.

- History of Present Illness (HPI):

- Provide a detailed chronological narrative of the current illness, including the onset, progression, and any interventions taken.

- Include relevant positives and negatives.

- Past Medical History (PMH):

- Summarize the patient’s past medical conditions , surgeries, and hospitalizations.

- Include any chronic illnesses, medications, and allergies.

- Medications:

- List and briefly describe the patient’s current medications, including dosage and frequency.

- Clearly state any allergies the patient has and describe the nature of the reaction.

- Social History:

- Include information about the patient’s lifestyle, occupation, habits (smoking, alcohol use, recreational drug use ), and living situation.

- Family History:

- Provide relevant information about the patient’s family history, especially regarding genetic or hereditary conditions.

- Review of Systems (ROS):

- Systematically go through each organ system and inquire about symptoms.

- Include both relevant positives and negatives.

- Physical Examination:

- Summarize the findings from the physical examination.

- Include vital signs and any relevant measurements.

- Diagnostic Tests:

- Present the results of any relevant diagnostic tests, such as laboratory results, imaging studies, or procedures.

- Include normal reference ranges for context.

- Assessment:

- Provide a concise summary of the patient’s condition, highlighting the most significant issues.

- Use medical case study writing terminology appropriately.

- Outline the proposed plan of action, including immediate and long-term goals.

- Discuss medications, interventions, further diagnostic tests, and follow-up plans.

- Discussion/Impressions:

- Include any differential diagnoses considered and the reasoning behind the final diagnosis.

- Discuss any challenging aspects of the case or areas of uncertainty.

- Summary/Conclusion:

- Summarize the key points of the case presentation .

- Emphasize any important takeaways or learning points.

- Questions/Comments:

- Invite questions or comments from colleagues or supervisors.

- Be prepared to discuss and defend your reasoning.

Remember to adapt the structure based on the specific requirements of your audience and the nature of the case. Keep the presentation clear, concise, and focused on the relevant details.

Check our Blog for guidance on guide to preparing case reports for the Journal of Medical Case Reports

In summary, a well-structured case presentation is essential for effective communication in various professional settings, including healthcare case reports, business, and academia. The presentation should begin with a clear introduction, providing context and setting the stage for the case. The inclusion of relevant background information, followed by a concise presentation of the facts, ensures a comprehensive understanding. The analysis and interpretation of the case should be thorough, highlighting key issues and potential solutions. A structured case report approach to presenting supporting evidence enhances credibility. Finally, a well-crafted conclusion summarizing key takeaways and recommendations leaves a lasting impression. Overall, Pubrica provides a systematically organized case presentation, enhances clarity, facilitates discussion, and ultimately contributes to informed decision-making.

Related Topics

☛ Medical data analytics and machine learning ☛ scientific communication services ☛ Scientific journal publication services

Research your Services with our experts

Delivered on-time or your money back

Give yourself the academic edge today

Each order includes

- On-time delivery or your money back

- A fully qualified writer in your subject

- In-depth proofreading by our Quality Control Team

- 100% confidentiality, the work is never re-sold or published

- Standard 7-day amendment period

- A paper written to the standard ordered

- A detailed plagiarism report

- A comprehensive quality report

WhatsApp us

Case study presentation: A comprehensive guide

This comprehensive guide covers everything from the right topic to designing your slides and delivering your presentation.

Raja Bothra

Building presentations

Table of contents

Hey there, fellow content creators and business enthusiasts!

If you're looking to take your presentations to the next level, you've come to the right place.

In today's digital age, a powerful case study presentation is your secret weapon to leave a lasting impression on potential clients, colleagues, or stakeholders.

It's time to demystify the art of case study presentations and equip you with the knowledge to create compelling and persuasive slides that showcase your expertise.

What is a case study?

Before we jump into the nitty-gritty details of creating a compelling case study presentation, let's start with the basics. What exactly is a case study? A case study is a detailed analysis of a specific subject, often focusing on a real-world problem or situation. It serves as a valuable tool to showcase your expertise and the impact your solutions can have on real issues.

Case study presentations are not just reports; they are powerful storytelling tools designed to engage your audience and provide insights into your success stories. Whether you're a marketer, a salesperson, or an educator, knowing how to present a case study effectively can be a game-changer for your business.

Why is it important to have an effective case study presentation?

The importance of a well-crafted case study presentation cannot be overstated. It's not just about sharing information; it's about convincing your audience that your product or service is the solution they've been looking for. Here are a few reasons why case study presentations matter:

Generating leads and driving sales

Picture this: a potential customer is exploring your website, trying to figure out if your product or service is the right fit for their needs. An effective case study can be the clincher, demonstrating how your offering has guided other businesses to success. When prospects witness a proven track record of your product or service making a difference, they are more inclined to place their trust in you and forge a partnership. In essence, case studies can be the catalyst that transforms casual visitors into paying customers.

Building credibility and social proof

In the realm of business, credibility is akin to gold. A well-crafted case study is your gateway to establishing authority and unveiling the remarkable value you bring to the table. It's not just you saying you're the best; it's your satisfied clients proclaiming it through their experiences. Every compelling case study is a testimonial in itself, a testament to your capability to deliver tangible results. In essence, it's a vote of confidence from others in your field, and these votes can be a potent motivator for potential clients.

Educating and informing your target audience

Education is a cornerstone of building lasting relationships with your audience. Case studies are an invaluable tool for teaching potential clients about the merits of your product or service and how it can address their specific challenges. They're not just stories; they're lessons, revealing the real-world benefits of what you offer. By doing so, you position your company as a thought leader in your industry and cultivate trust among your audience. You're not just selling; you're empowering your audience with knowledge.

Increasing brand awareness

Your brand deserves to be in the spotlight. Case studies can serve as a beacon, promoting your brand and its offerings across a multitude of platforms. From your website to social media and email marketing, case studies help you amplify your brand's presence and appeal. As you increase your reach and visibility, you also draw the attention of new customers, who are eager to experience the success stories they've read about in your case studies.

Different types of case study presentation

Now that you understand why case study presentations are vital, let's explore the various types you can use to showcase your successes.

Business case studies presentation : Business case studies presentation focus on how your product or service has impacted a specific company or organization. These are essential tools for B2B companies, as they demonstrate the tangible benefits your solution brings to other businesses.

Marketing case studies presentation : If you're in the marketing game, you've probably come across these frequently. Marketing case studies dive into the strategies and tactics used to achieve specific marketing goals. They provide insights into successful campaigns and can be a great resource for other marketers.

Product case studies presentation : For companies that offer products, a product case study can be a game-changer. It shows potential clients how your product functions in the real world and why it's the best choice for them.

KPIs and metrics to add in case study presentation

When presenting a case study, you're not just telling a story; you're also showcasing the concrete results of your efforts. Numbers matter, and they can add significant credibility to your presentation. While there's a vast array of key performance indicators (KPIs) and metrics you can include, here are some that you should definitely consider:

Conversion rate : This metric is a reflection of how effective your product or service has been in driving conversions. It demonstrates the rate at which visitors take the desired actions, whether it's signing up for your newsletter, making a purchase, or any other valuable engagement.

ROI (return on investment) : It's the financial impact that counts, and ROI is the king of financial metrics. It's a clear indicator of how your solution has provided value, showing the return on the investment made by your client.

Engagement metrics : Engaging your audience is a vital part of the puzzle. Metrics like click-through rates and social media interactions reveal how effectively your solution has drawn people in and kept them engaged.

Customer satisfaction : A satisfied customer is a loyal customer. Showcase customer satisfaction scores or even better, let the clients themselves tell their stories through testimonials. These scores and testimonials are potent proof of your ability to meet and exceed expectations.

Sales growth : When applicable, include data on how your solution has catalyzed sales growth. Sales growth is a pivotal indicator of the practical, real-world impact of your product or service.

However, it's important to note that there are some general KPIs and metrics that are commonly used in case study presentations. These metrics are not only universal but also highly effective in conveying the success of your case study:

- Website traffic : The number of visitors to your website over a specified period is an important indicator of the reach and impact of your case study. It shows how many people were interested enough to seek more information.

- Conversion rate : This percentage reveals how successful your website is at converting visitors into taking a desired action. Whether it's signing up for a newsletter, making a purchase, or any other specific action, a high conversion rate signifies effective engagement.

- Customer lifetime value (CLV) : The CLV is a valuable metric, representing the average amount of money a customer spends with your company over their lifetime. It's a testament to the long-term value your product or service provides.

- Average order value (AOV) : The AOV showcases the average amount of money a customer spends in a single transaction. It's a metric that demonstrates the immediate value your solution offers.

- Net promoter score (NPS) : This customer satisfaction metric measures how likely your customers are to recommend your company to others. A high NPS indicates satisfied customers who can become advocates for your brand.

Incorporating these KPIs and metrics not only adds credibility to your case study presentation but also provides a well-rounded view of your success story. It's the data that speaks the loudest and validates the impact of your product or service.

How to structure an effective case study presentation

Structuring an effective case study presentation is essential for conveying information clearly and persuasively to your audience. Whether you're presenting to colleagues, clients, or students, a well-organized case study presentation can make a significant impact. Here are some key steps to structure your case study presentation effectively:

1. Introduction :

Start with a brief introduction that sets the stage for your case study. Explain the context, the purpose of the study, and the key objectives you aim to achieve. This section should pique the audience's interest and provide a clear understanding of what to expect.

2. Background and context :

Provide a comprehensive overview of the background and context of the case study. This might include the industry, company, or problem under consideration. Explain why the case study is relevant and the issues it addresses. Make sure your audience understands the "why" before delving into the details.

3. Problem statement :

Clearly define the problem or challenge that the case study focuses on. This is a critical element as it helps the audience grasp the significance of the issue at hand. Use data and evidence to support your claims and emphasize the real-world impact of the problem.

4. Methodology :

Describe the methods and approach you used to analyze the case. This section should outline your research process, data collection tools , and any methods or frameworks employed. It's important to demonstrate the rigor of your analysis and data sources.

5. Findings and analysis :

Present the key findings and insights from your case study. Use data, charts, graphs, and visuals to make the information more accessible and engaging. Discuss your analysis and provide explanations for the findings. It's crucial to show a deep understanding of the problem and its implications.

6. Solution or action plan :

Outline the solution, recommendations, or action plan you've developed based on your analysis. Explain the rationale behind your proposed solution and how it directly addresses the problem. Include implementation steps, timelines, and any potential obstacles.

7. Results and outcomes :

Highlight the results and outcomes of implementing your solution, if applicable. Use before-and-after comparisons, success metrics, and tangible achievements to illustrate the effectiveness of your recommendations. This helps demonstrate the real-world impact of your work.

8. Lessons learned :

Share any lessons learned from the case study. Discuss what worked well, what didn't, and any unexpected challenges. This reflective element shows that you can extract valuable insights from the experience.

9. Conclusion :

Summarize the key takeaways from your case study and restate its significance. Make a compelling case for the importance of the findings and the applicability of the solution in a broader context.

10. Recommendations and next steps :

Provide recommendations for the future, including any further actions that can be taken or additional research required. Give your audience a sense of what to do next based on the case study's insights.

11. Q&A and discussion :

Open the floor for questions and discussion. Encourage your audience to ask for clarification, share their perspectives, and engage in a constructive dialogue about the case study.

12. References and appendices :

Include a list of references, citations, and any supplementary materials in appendices that support your case study. This adds credibility to your presentation and allows interested individuals to delve deeper into the subject.

A well-structured case study presentation not only informs but also persuades your audience by providing a clear narrative and a logical flow of information. It is an opportunity to showcase your analytical skills, problem-solving abilities, and the value of your work in a practical setting.

Do’s and don'ts on a case study presentation

To ensure your case study presentation hits the mark, here's a quick rundown of some do's and don'ts:

- Use visual aids : Visual aids like charts and graphs can make complex data more digestible.

- Tell a story : Engage your audience by narrating a compelling story.

- Use persuasive language : Convincing your audience requires a persuasive tone.

- Include testimonials : Real-life experiences add authenticity to your presentation.

- Follow a format : Stick to a well-structured format for clarity.

Don'ts:

- Avoid jargon : Keep it simple and free from industry jargon.

- Don't oversell : Be honest about your product or service's capabilities.

- Don't make it too long : A concise presentation is more effective than a lengthy one.

- Don't overload with data : Focus on the most relevant and impactful data.

Summarizing key takeaways

- Understanding case studies : Case studies are detailed analyses of specific subjects, serving to showcase expertise and solution impact.

- Importance of effective case study presentations : They generate leads, build credibility, educate the audience, and increase brand awareness.

- Types of case study presentations : Business, marketing, and product case studies focus on different aspects of impact.

- KPIs and metrics : Key metrics, such as conversion rates, ROI, engagement metrics, customer satisfaction, and sales growth, add credibility.

- Structuring an effective case study presentation : Follow a structured format with an introduction, background, problem statement, methodology, findings, solution, results, lessons learned, conclusion, recommendations, and Q&A.

- Do's : Use visuals, tell a compelling story, use persuasive language, include testimonials, and follow a structured format.

- Don'ts: Use jargon, oversell, make it too long, or overload with unnecessary data.

1. How do I create a compelling case study presentation?

To create a compelling case study presentation, you can use a case study template that will help you structure your content in a clear and concise manner. You can also make use of a case study presentation template to ensure that your presentation slides are well-organized. Additionally, make your case study like a pro by using real-life examples and a professional case study format.

2. What is the best way to present a case study to prospective clients?

When presenting a case study to prospective clients, it's essential to use case study presentation template. This will help you present your findings in a persuasive way, just like a professional presentation. You can also use a powerpoint case study template to make your case study presentation in no time. The length of a case study can vary depending on the complexity, but a well-written case study is key to helping your clients understand the value.

3. Where can I find popular templates to use for my case study presentation?

You can find popular case study presentation powerpoint templates online. These templates are specifically designed to help you create a beautiful case study that will impress your audience. They often include everything you need to impress your audience, from the case study format to the presentation deck. Using templates you can use is one of the best ways to create a case study presentation in a professional and efficient manner.

4. What is the purpose of a case study in content marketing, and how can I use one effectively?

The purpose of a case study in content marketing is to showcase real-world examples of how your product or service has solved a problem or added value to clients. To use a case study effectively, write a case study that features a relevant case study example and use a case study like a pro to make your case. You can also embed your case study within your content marketing strategy to help your clients and prospective clients understand the value your business offers.

5. How can I ensure that my case study presentation stands out as the best in my industry?

To ensure your case study presentation stands out as the best, you can follow a compelling business case study design. Use a case study template that includes everything you need to present a compelling and successful case, just like PowerPoint case study presentations. Make sure your case study is clear and concise, and present it in a persuasive way. Using real-life examples and following the sections in your template can set your presentation apart from the rest, making it the best case study presentation in your field.

Create your case study presentation with prezent

Prezent, the communication success platform designed for enterprise teams, offers a host of valuable tools and features to assist in creating an impactful case study presentation.

- Brand-approved design : With access to over 35,000 slides in your company's brand-approved design, your case study presentation can maintain a consistent and professional look that aligns with your corporate brand and marketing guidelines.

- Structured storytelling : Prezent helps you master structured storytelling by offering 50+ storylines commonly used by business leaders. This ensures your case study presentation follows a compelling and coherent narrative structure.

- Time and cost efficiency : Prezent can save you valuable time and resources. It can help you save 70% of the time required to make presentations and reduce communication costs by 60%, making it a cost-effective solution for creating case study presentations.

- Enterprise-grade security : Your data's security is a top priority for Prezent. With independent third-party assurance, you can trust that your sensitive information remains protected while creating and sharing your case study presentation.

In summary, Prezent empowers you to create a compelling case study presentation by offering personalized audience insights, brand-compliant designs, structured storytelling support, real-time collaboration, efficiency gains, and robust data security. It's a comprehensive platform for achieving communication success in the world of enterprise presentations.

Are you ready to take your case study presentations to the next level? Try our free trial or book a demo today with Prezent!

More zenpedia articles

Nine steps to build a successful internal communication strategy?

What is informal communication: Types, differences & benefits

What is strategic communication and why does it matter?

Get the latest from Prezent community

Join thousands of subscribers who receive our best practices on communication, storytelling, presentation design, and more. New tips weekly. (No spam, we promise!)

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

TEACHING TIPS: TWELVE TIPS FOR MAKING CASE PRESENTATIONS MORE INTERESTING *

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Craig J, Kopala L. Medical Teacher 1995;17(2):161-6 .

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

1. SET THE STAGE

Prepare the audience for what is to come. If the audience is composed of people of mixed expertise, spend a few minutes forming them into small mixed groups of novices and experts. Explain that this is an opportunity for the more junior to learn from the more senior people. Tell them that the case to be presented is extremely interesting, why it is so and what they may learn from it. The primary objective is to analyze the clinical reasoning that was used rather than the knowledge required, although the acquisition of such knowledge is an added benefit of the session. A “well organized case presentation or clinicopathological conference incorporates the logic of the workup implicitly and thus makes the diagnostic process seem almost preordained”.

A psychiatry resident began by introducing the case as an exciting one, explaining the process and dividing the audience into teams mixing people with varied expertise. He urged everyone to think in ‘real time’ rather than jump ahead and to refrain from considering information that is not normally available at the time: for example, a laboratory report that takes 24 hours to obtain be assessed in the initial workup.

2. PROVIDE ONLY INITIAL CUES AT FIRST

Give them the first two to live cues that were picked up in the first minute or two of the patient encounter either verbally, or written on a transparency. For example, age, sex race and reason for seeking medical help. Ask each group to discuss their first diagnostic hypotheses. Experts and novices will learn a great deal from each other at this stage and the discussions will be animated. The initial cues may number only one or two and hypothesis generation occurs very quickly even in the novices. Indeed, the only difference between the hypotheses of novices and those of experts is in the degree of refinement, not in number.

It is Saturday afternoon and you are the psychiatric emergency physician. A 25-year-old male arrives by ambulance and states that he is feeling suicidal. Groups talked for 4 minutes before the resident called for order to commence step three.

3. ASK FOR HYPOTHESES AND WRITE THEM UP ON THE BLACKBOARD

Call for order and ask people to offer their suggested diagnoses and write these up on a board or transparency.

The following hypotheses were suggested by the groups and the resident wrote them on a flip chart: depression, substance abuse, recent social stressors-crisis, adjustment disorder, organic problem, dysthymia, schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder. The initial three or four bits of information generated eight hypotheses.

4. ALLOW THE AUDIENCE TO ASK FOR INFORMATION

After all hypotheses have been listed instruct the audience to ask for the information they need to confirm or refute these hypotheses. Do not allow them to ‘jump the gun’ by asking for a test result, for example, that would not have been received within the time frame that is being re-lived. There will be a temptation to move too fast and the exercise is wasted if information is given too soon. Recall that the purpose is to help them go through a thinking process which requires time.

Teachers participating in this exercise will receive much diagnostic information about students’ thinking at this stage. Indeed, an interesting teaching session can be conducted by simply asking students to generate hypotheses without proceeding further. There is evidence to suggest that when a diagnosis is not considered initially it is unlikely to be reached over time, Hence it is worth spending time with students to discuss the hypotheses they generate before they proceed with an enquiry.

Directions to the group were to determine what questions they would like to ask, based on gender, age and probabilities, to support or exclude the listed diagnostic possibilities. A sample of question follow:

Does he work? No, he's unemployed.

Does he drink? one to three beers a week.

Why now? He's been feeling worse and worse for the last 3 weeks.

Social support? He gives alone. Has no girlfriend.

Appearance? Looks his age. Not shaved today. No shower in 3 days.

Cultural background? Refugee from Iraq. Muslim.

How did he get here? He spent 4 years in a refugee camp after spending 4 months walking to Pakistan from Iraq. He left Iraq to avoid military service.

Suicide thoughts? Increasing the last 3 weeks. He was admitted in December and has been taking chloral hydrate.

This step took 13 minutes.

5. HAVE THE AUDIENCE RE-FORMULATE THEIR LIST OF HYPOTHESES

After enough information has been gained to proceed, ask them to resume their discussion about the problem and reformulate their diagnostic hypotheses in light of the new information. Instruct them to discuss which pieces of information changed the working diagnosis and why. Call for order again and ask people what they now think.

After allowing the group to talk for a few minutes, the resident asked them if there was enough information to strike off any hypotheses or if new hypotheses should be added to the list. One more possibility was added, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). One group's list of priorities was major affective disorder with psychosis, schizophrenia, personality disorder. Another group also placed affective disorder first followed by organic mood disorder.

This step took 25 minutes.

6. FACILITATE A DISCUSSION ABOUT REASONING

Alter the original lists of hypotheses on the board in light of the discussion, or allow one member from each group to alter their own lists. By the use of open-ended questions encourage a general discussion about the reasons a group has for preferring one diagnosis over another.

A general discussion ensued about reasons for these priorities. Then the list was altered so that it read: schizophrenia, personality disorder, PTSD, major affective disorder with psychosis, organic mood disorder.

7. ALLOW ANOTHER ROUND OF INFORMATION SEEKING

Continue with another round of information and small-group discussion or else allow the whole group to interact. By giving information only when asked for and only in correct sequence, each person is challenged to think through the problem.

More information was sought, such as: form of speech? eye contact? affect? substance use? After 5 minutes the resident asked if there were only lab tests they would like. The group asked for thyroid stimulating hormone, T4, electrolytes and were given the results. They also asked for the results of the physical examination and were told that the pulse was 110 and the thyroid was enlarged. At this point some hypotheses were removed from the list.

8. ASK GROUPS TO REACH A FINAL DIAGNOSIS

When there is a lull in the search for information, ask the groups to reach consensus on their final diagnosis, given the information they have. Allow discussion within the groups.

9. CALL FOR EACH GROUP'S FINAL DIAGNOSIS

On each group's list of hypothesis, star or underline the final diagnosis.

The group decided that the most likely diagnosis was affective disorder with psychosis, the actual working diagnosis of the patient.

10. ASK FOR MANAGEMENT OPTIONS

If there is enough time, ask them to form small groups again to discuss treatment options, or conduct the discussion as a large group. Again ask for the reasons why one approach is preferred over another. Particularly ask the experts in the room for their reasoning so that the novices can learn from them.

11. SUMMARIZE

By the time the end is in sight the audience will be so involved that they will not wish to leave. However, 5 minutes before time, call for order and summarize the session. Highlight the key points that have been raised and refer to the objective of the session.

We are now at the end of our time. You have all had the opportunity to use your clinical reasoning skills to generate several hypotheses which are shown on the board. Initially you thought it possible that this man could have any one of a number of diagnoses including depression, substance abuse, adjustment disorder with depressed mood, organic mood disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder. With further information the possible diagnosis shifted to include schizophrenia and personality disorder as well as depression with psychotic features. Finally the diagnosis of depression or mood disorder with psychosis was most strongly supported because of the history of consistently depressed mood over several months, along with disturbed sleep, poor appetite, weight loss, decreased energy and diminished interest in most activities. The initially abnormal thyroid test proved to be a red herring so organic mood disorder related to hyper- or hypo-thyroidism was excluded. Additionally absence of vivid dreams involving a traumatic event made a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder unlikely. Although a diagnosis of schizophrenia could not be totally excluded, this seemed less likely given the findings.

12. CLOSE THE SESSION WITH POSITIVE FEEDBACK

In some respects, but only some, teaching is like acting and one should strive to leave them not laughing as you go, but feeling that they have learned something.

The more novice members of the group have learned from the more experienced and all your suggestions have been valid. It has been interesting for me to follow your reasoning and compare it with mine when I actually saw this man. You have given me a different perspective as you thought of things I had not, and I thank you for your participation.

Although case presentation should be a major learning experience for both novice and experienced physicians they are often conducted in a stultifying way that defies thought. We have presented a series of steps which, if followed, guarantee active participation from the audience and ensure that if experts are in the room their expertise is used. Physicians have been moulded to believe that teaching means telling and, as a consequence, adopt a remote listening stance during case presentations. Indeed the back row often use the time to catch up on much needed sleep! Changing the format requires courage. We urge you to try out these steps so that both you and your audience will learn from and enjoy the process.

- PDF (33.2 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Presenting patient cases is a key part of everyday clinical practice. A well delivered presentation has the potential to facilitate patient care and improve efficiency on ward rounds, as well as a means of teaching and assessing clinical competence. 1 The purpose of a case presentation is to communicate your diagnostic reasoning to the listener, so that he or she has a clear picture of the ...

î 3dwlhqw ,qirupdwlrq 'hprjudsklfv djh udfh vh[ 5hylhz ri 6\vwhpv 526 shuwlqhqw srvlwlyhv qhjdwlyhv &klhi &rpsodlqw && 3k\vlfdo ([dplqdwlrq 3( lqfoxglqj