18 Moral Dilemma Examples

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

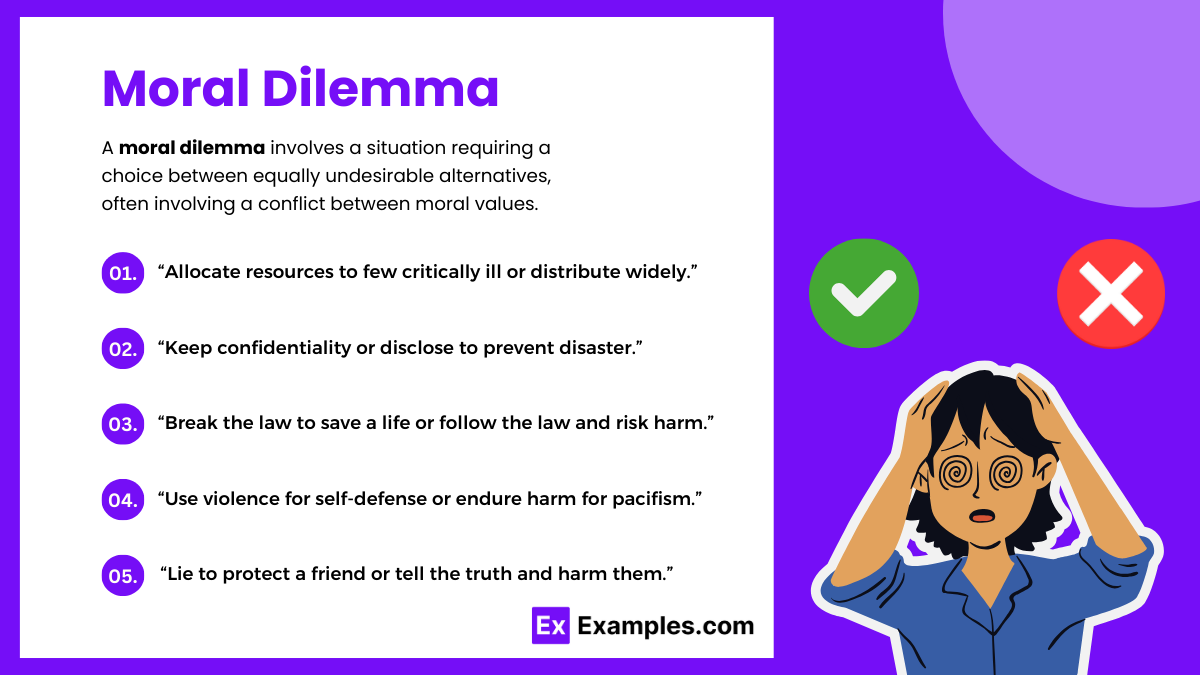

A moral dilemma is a situation in which an individual must choose between two moral options. Each option has advantages and disadvantages that contain significant consequences.

Choosing one option means violating the ethical considerations of the other option. So, no matter which option is selected, it both upholds and violates at least one moral principle.

When moral dilemmas are discussed formally, the individual that must make the decision is referred to as the agent .

Moral Dilemma Features

McConnell (2022) identifies the crucial features of a moral or ethical dilemma :

- The agent (person) is required to do one of two moral options

- The agent (person) is capable of doing each one

- The agent (person) cannot do both

McConnell explains that the agent should choose option A, but at the same time, the agent should choose option B. All things considered, both options are equivalently positive and negative, but in different aspects.

Thus, no matter which option is chosen, it will result in a moral failure.

Types of Moral Dilemmas

- Epistemic: This type of moral dilemma is when the person has no idea which option is the most morally acceptable. Although in many moral dilemmas it can be somewhat clear which option should take precedence, in the epistemic moral dilemma , the matter is ambiguous.

- Ontological: This is a moral dilemma in which the options available are equal in every respect. The person knows and has a clear understanding that both options are equivalent. Most experts on morality agree that ontological moral dilemmas are genuine dilemmas.

- Self-imposed: This is the type of moral dilemma that the person has created themselves. They have engaged in a wrongdoing of some kind and are then faced with resolving the matter.

- World-imposed: When the moral dilemma is brought about by others and the person must resolve the matter, it is referred to as a world-imposed moral dilemma, and is also often an example of a social dilemma . The person is in the situation, but not due to any wrongdoing or mistake they are responsible for.

- Obligation : Some moral dilemmas involve options in which the person feels they must enact each one. It is a sense of responsibility to engage both options that creates the moral dilemma. The tension arises because they can only choose one, but they are obligated to do both.

- Prohibition: A moral dilemma in which each option is reprehensible is called a prohibition dilemma . Each option would normally not be considered due to its unethical nature. However, the person must choose.

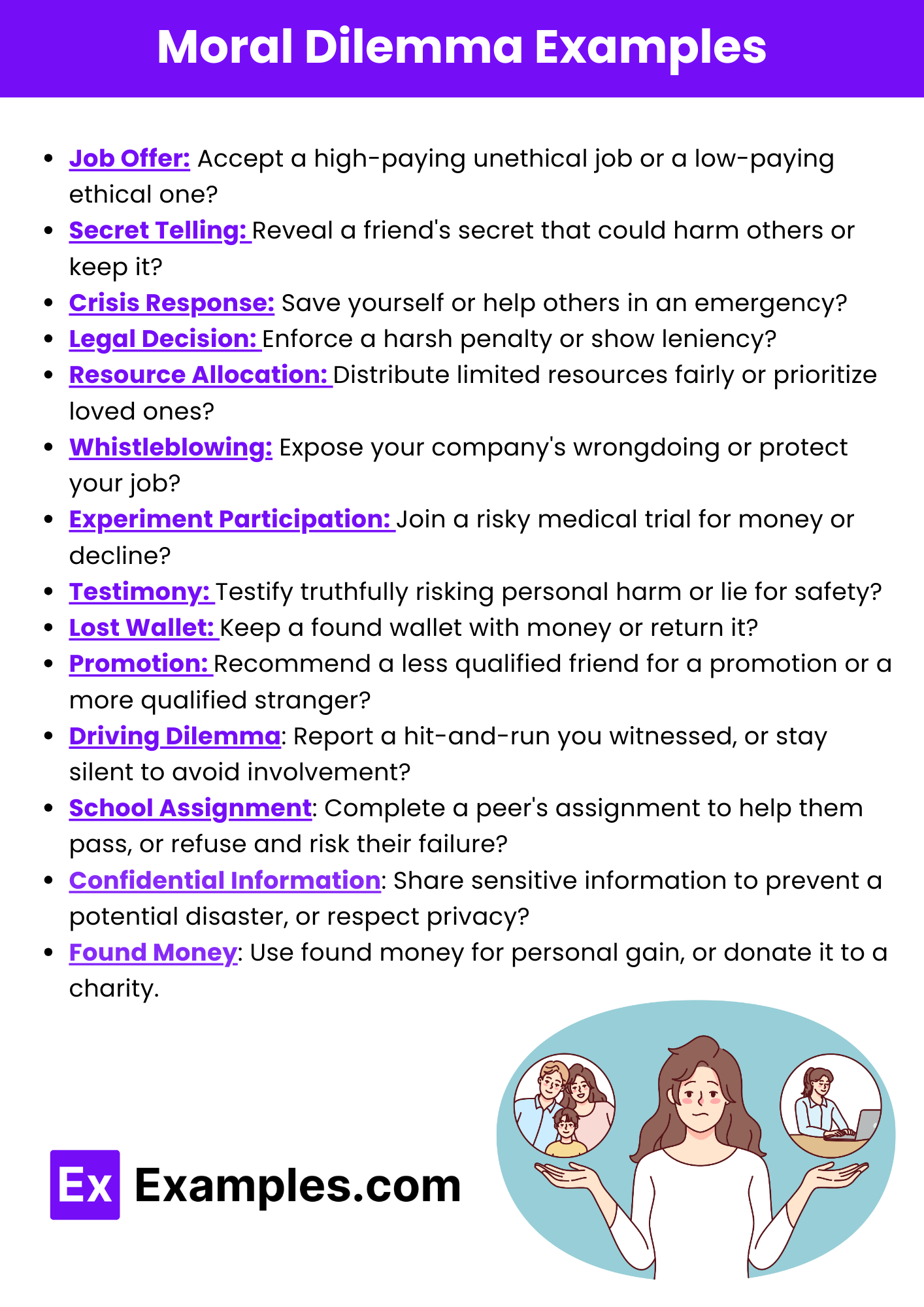

Moral Dilemma Examples

1. Exposing Your Best Friend: The person (aka the ‘agent’) is in a supervisory position but recently discovered that his best friend has been faking the numbers on several sales reports to boost his commissions.

Type: This is a self-imposed moral dilemma . The person has not done any wrongdoing, but they are in the position to decide whether to expose their friend’s unethical behavior .

2. Tricking a Loved One with Alzheimer’s: In this scenario, a loved one has been placed in a special residential center, which is expensive. Their children don’t have the funds to pay, but the loved one does. Unfortunately, the only way to access those funds is to trick the loved one into revealing their bank account information.

Type: This seems to be an obligation moral dilemma . The person feels they must take care of their loved one’s expenses, but they also feel a duty to respect their loved one’s autonomy and not deceive them.

3. Cheating on a Boyfriend: The person/agent cheated on their boyfriend while at a conference, which occurred right after a huge fight where they both said they wanted to break up. However, now that they’re back together, the question becomes: should the boyfriend be told?

Type: This is a self-imposed moral dilemma , as the person’s actions led to the situation where they must decide whether to confess their infidelity.

4. Selling a Used Car: The person has two close friends. One is considering buying a car from the other. They know the car has a serious problem with the engine, but their friend is not disclosing it.

Type: This can be seen as an ontological moral dilemma , as the person must choose between two equivalent actions: betraying the trust of one friend by revealing the car’s problems or betraying the trust of the other friend by staying silent.

5. Recalling a Faulty Product: The CEO of a large corporation has been informed that one of their products causes cancer in lab rats. The mortality rate is low and the company has spent millions on R&D and marketing. Recalling the product could mean bankruptcy and thousands of lost jobs.

Type: This could be a world-imposed moral dilemma as the person/agent didn’t personally contribute to the faulty product but must decide whether to recall the product or risk public health.

6. Global Supply Chains: The BOD knows that the rare Earth minerals they need for their electronics products are being mined by children. Not using that source means the company would be required to raise the price of its products considerably. And that means competitors will win huge market share.

Type: This is an obligation dilemma . The person feels obligated to both keep their products affordable (and their company competitive) and to avoid supporting unethical labor practices.

7. Admitting a Mistake: The person only analyzes part of the data involved in a pharmaceutical study so that the medication looks effective. A year later, the BOD is charged with a crime because the government learned that the medication causes a severe health issue in users.

Type: This is a self-imposed dilemma because the agent’s decision to only analyze part of the data led to the current situation.

8. In Child Protection Services: The ‘agent’ in this dilemma is a case worker. They know that charges against a parent were fabricated by a vengeful ex, but yet the rules state that charges must be filed and the children removed from the household, most likely for several months until a full investigation has been completed.

Type: This could be an epistemic dilemma because the person doesn’t know which action – following the protocol or not filing charges knowing they were fabricated – is the most morally correct.

9. Playground Accident at School: The agent’s co-teacher was looking at their phone on the playground when one of the students under their supervision fell off the equipment and broke their arm. If the person tells the truth, the co-teacher, who is supporting three children as a single parent, will be fired.

Type: This could be seen as an ontological dilemma , as the person must choose between two equally significant outcomes: telling the truth and potentially causing their co-teacher to lose their job, or staying silent and potentially putting the school and other students at risk.

10. In Geo-Politics: The president of a company knows that they are dependent on doing business with another country that has severe human rights violations. If they move out of that market it will mean huge losses. If they stay, it means putting money in the pockets of people that commit crimes against humanity.

Type: This might be classified as a prohibition dilemma , as both options – supporting a regime that violates human rights or causing significant financial loss to the company and its stakeholders – are morally objectionable.

11. Conflict of Professional Ethics: Imagine a journalist finds sensitive but vital information about a potential major scandal involving a beloved public figure who happens also to be the journalist’s dear friend.

Type: This represents a self-imposed dilemma , as the journalist must reconcile their professional obligation with their personal relationship.

12. Prioritizing Elder Care: Imagine a working individual struggling to balance work responsibilities with eldercare. On one hand, they want to provide proper care for their elderly parent but on the other hand, they fear losing their job.

Type: This could be classified as an obligation dilemma , as the individual is torn between two significant responsibilities.

13. Intellectual Property Misuse: A computer engineer discovers their colleague is misusing intellectual property from a previous employer to boost productivity at the current firm.

Type: This scenario represents an ontological moral dilemma , where the engineer must choose between reporting their colleague and protecting the workplace.

14. Revealing Confidential Information: An employee learns that their company’s financial health is more severe than communicated publicly. They fear that if they don’t warn their co-workers, they all risk losing their jobs without prior notice.

Type: This could be seen as a world-imposed moral dilemma , as the employee had no hand in creating the financial instability but must decide how to handle the information.

15. Exploitative Marketing: A marketing manager at a fast-food company is asked to develop campaigns targeting low-income neighborhoods, where obesity rates are already high.

Type: This represents an obligation dilemma , as the manager is expected to fulfill their job duty while battling against contributing to societies’ health problem.

16. Academic Dishonesty: A student discovers their friend plagiarizing an entire assignment. On one hand, they feel they should report the violation, but they also fear losing their friend.

Type: This is a self-imposed dilemma as the student’s action led to the situation where they must decide whether to uphold academic integrity or maintain their friendship.

17. Unethical Labor Practices: A manufacturing company explicitly doesn’t use sweatshop labor. It’s discovered that their major supplier uses such practices.

Type: This is an obligation dilemma , as the company feels a responsibility to its reputation and ethical standards, but severing ties with the major supplier could risk business operations.

18. Business Versus Environment: A construction company discovers an endangered species habitat in an area planned for building a lucrative housing project.

Type: This is an epistemic dilemma , as the company has to choose between its economic interests and environmental responsibilities not knowing which is the morally correct decision.

Applications of Moral Dilemmas

1. in nursing .

According to Arries (2005), among all of the professionals in healthcare, nurses have the most frequent interactions with patients.

As a result, they confront moral dilemmas on a regular basis, and often experience severe emotional distress.

They often must balance obligations regarding professional duties and personal convictions involving their values and beliefs.

In fact, nurses face a wide range of moral dilemmas. Rainer et al. (2018) conducted an integrative review of published research from 2000 – 2017 which dealt with ethical dilemmas faced by nurses.

The review identified several main categories or moral dilemmas: end-of-life issues, conflicts with physicians, conflicts with patient family members, patient privacy matters, and organizational constraints.

In a meta-analysis of nine studies in four countries, de Casterlé et al. (2008) examined the moral reasoning of nurses based on Kohlberg’s (1971) theory of moral development.

The study used an adapted version of the Ethical Behaviour Test (EBT) to measure nurses’ moral reasoning as it applies to practical nursing scenarios (de Casterle´ et al. 1997).

The results suggested that nurses tended to function at a conventional level of moral reasoning, rather than at a higher, postconventional level in Kohlberg’s stages.

2. In Journalism

Many people that enter the field of journalism do so out of noble goals to promote truth, help the public stay informed, and reveal unethical practices in society.

The very nature of those goals leads to journalists being immersed in moral dilemmas stemming from a variety of issues.

Sources Journalists must gather information from sources that can be reluctant to reveal their identity. This presents the moral dilemma of somehow establishing credibility for one’s information, but at the same time protecting the rights and wishes of an anonymous source.

Victim’s Rights Protecting victims’ rights to privacy can be in direct conflict with the public’s right to know. This produces an ethical quandary that nearly every journalist will face in their career. This can be particularly tricky when dealing with public figures, elected officials, or children.

Conflicts of Interest Conflicts of interest come into play in journalism in several situations. Journalists are supposed to be impartial and cover stories fairly and objectively. However, conflicts of interest can emerge when the story might impact an advertiser negatively or reflect poorly on the company’s ownership.

Accuracy Particularly troublesome in the era of new media news is the moral dilemma regarding the accuracy of information presented in coverage. On the one hand, journalists are obligated to provide the audience with information that is valid. That takes time. On the other hand, being first has always been a priority in the journalism profession. Accuracy is tied directly to credibility, but at the same time, being second to go public with news tarnishes the agency’s reputation.

Credibility Deuze and Yeshua (2001) point out that one core moral dilemma in journalism centers on how to establish credibility in the age of social media and the lightning speed of the Internet. New media journalists struggle to establish credibility in an environment crowded with gossip, amateur journalists, and fake news (Singer, 1996).

3. In Business

There are no shortage of moral dilemmas in the business world, no matter how large or small the company (Shaw & Barry, 2015).

A small sample of ethical issues are described below.

Product Quality vs. Profit Nearly every item made can be produced to a higher standard. That is not the problem. The problem is that those higher standards usually entail higher costs. So, the tradeoff becomes an issue of competing priorities : product quality or product profitability.

Outsourcing Labor This seems to be a decision that a lot of US corporations have already completed. Offshoring labor is usually cheaper. But, it comes at a cost to the homeland. Fewer jobs means a weaker economy and possibly an array of psychosocial dysfunctions. If you ask the various BODs however, they will tell you that they have to honor their fiduciary obligation to make the most profit for the company they run. Often, that means offshoring jobs.

Employee Social Media Behavior On the one hand, what people do in their personal time is supposed to be just that, personal. On the other hand, each employee represents the company and if they engage in behavior online that reflects poorly on the company, then that can justify terminating their contract.

Honest Marketing It can be easy to stretch the truth a little bit to make a product or service look its best. How far to stretch that line is where the moral dilemma forms. In cases that are basically inconsequential, like foods and such, a little gloss is relatively harmless. However, when it comes to products that are consequential such as pharmaceuticals and insurance policies, the moral dilemma is so serious that the government has legislated marketing rules and regulations that must be strictly followed.

Labor Practices Many countries have strict laws about labor practices that involve child labor and working conditions. But, many countries do not. Some of the labor practices in those countries are absolutely shocking. Companies in industrialized countries such as in the EU are supposed to monitor their supply chains carefully. They can be held accountable if found in violation of their home country’s regulations. The moral dilemma occurs when the company feels it must turn a blind-eye to circumstances if it wants to stay in business.

Environmental Protection So many companies today are aware of their environmental footprint. They must make a calculated decision as to how much environmental damage they can accept in balance with expectations of their customers and damage to the environment. That balance is getting harder to ignore as societies become more environmentally conscious and social media increasingly powerful.

A moral dilemma is when an individual, referred to as an agent , is confronted with a situation in which they must choose between two or more moral options.

Unfortunately, each option has its own ramifications that make the choice between one or the other difficult.

Moral dilemmas are prevalent in our personal and professional lives. Several professions are especially rife with moral dilemmas. For instance, those in the healthcare industry must make decisions that can have life-and-death consequences.

Journalists must grapple with a range of moral dilemmas that involve establishing credibility of their content, verifying the accuracy of their information, plus issues of impartiality.

Business leaders today also cannot escape moral dilemmas. They must make decisions that impact employees, customers, and unseen individuals that work throughout fast supply chains.

As the world has become so interconnected, it seems that the number and severity of moral dilemmas continues to grow.

Arries, E. (2005). Virtue ethics: An approach to moral dilemmas in nursing. Curationis , 28 (3), 64-72.

de Casterlé, B. D., Grypdonck, M., & Vuylsteke-Wauters, M. (1997). Development, reliability, and validity testing of the Ethical Behavior Test: a measure for nurses’ ethical behavior. Journal of Nursing Measurement , 5 (1), 87-112.

de Casterlé, B., Roelens, A., & Gastmans, C. (1998). An adjusted version of Kohlberg’s moral theory: Discussion of its validity for research in nursing ethics. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 27 (4), 829-835.

de Casterlé, B. D., Izumi, S., Godfrey, N. S., & Denhaerynck, K. (2008). Nurses’ responses to ethical dilemmas in nursing practice: meta‐analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 63 (6), 540-549.

Deuze, M., & Yeshua, D. (2001). Online journalists face new ethical dilemmas: Lessons from the Netherlands. Journal of Mass Media Ethics , 16 (4), 273-292.

Kohlberg, L. (1971). Stages of moral development. Moral Education , 1 (51), 23-92.

McConnell, T. (2022 Fall edition). Moral Dilemmas. In Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (Eds.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived at https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2022/entries/moral-dilemmas/

Rainer, J., Schneider, J. K., & Lorenz, R. A. (2018). Ethical dilemmas in nursing: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27 (19-20), 3446–3461. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14542

Sainsbury, M. (2009). Moral dilemmas. Think, 8 , 57 – 63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1477175609000086

Shaw, W. H., & Barry, V. (2015). Moral issues in business . Cengage Learning.

Singer, J. B. (1996). Virtual anonymity: Online accountability and the virtuous virtual journalist. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 11 , 95–106

Strauß, N. (2022). Covering sustainable finance: Role perceptions, journalistic practices and moral dilemmas. Journalism , 23 (6), 1194-1212.

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Hepatitis Essay Topics Topics: 57

- Arthritis Paper Topics Topics: 58

- Asthma Topics Topics: 155

- Chlamydia Research Topics Topics: 52

- Dorothea Orem’s Theory Research Topics Topics: 85

- Heart Attack Topics Topics: 54

- Hypertension Essay Topics Topics: 155

- Communicable Disease Research Topics Topics: 58

- Breast Cancer Paper Topics Topics: 145

- Patient Safety Topics Topics: 148

- Nursing Theory Research Topics Topics: 207

- Heart Disease Topics Topics: 150

- Heart Failure Essay Topics Topics: 83

- STDs Essay Topics Topics: 134

- Tuberculosis Paper Topics Topics: 133

209 Ethical Dilemma Topics & Moral Issues

If you are searching for the most interesting ethical dilemma essay topics, welcome to our base! An ethical dilemma essay requires you to study difficult choices involving conflicting moral principles, personal values, and societal norms. Our ethical dilemma topics will guide you through medical ethics, business dilemmas, technology ethics, and more.

🤔 TOP 7 Ethical Debate Topics

🏆 best ethical dilemma essay topics, ⚖️ contemporary moral issues essay topics, 👍 catchy ethical dilemma essay examples, 🎓 interesting ethical dilemma essay ideas, 📌 easy ethical debate topics, 💧 personal ethical dilemma essay examples, 💡 simple ethical dilemma topics, ❓ more ethical debate research questions.

- Ethical Dilemma and an Ethical Lapse Difference

- The Ethical Dilemmas in Law

- The Lifeboat Case as an Ethical Dilemma

- Lego Company’s Core Values and Ethical Dilemmas

- Ethical Issues in Healthcare Essay: Ethical Dilemma

- Ethical Dilemmas in Nursing Practice

- Forensic Psychology Analysis: Ethical Dilemmas and Principles

- Ethical Dilemma in Homer’s “The Odyssey” Homer’s Odysseus faced such an ethical dilemma when he and his crew approached the area between Charybdis and Scylla as they were sailing.

- Apple Inc.: The Ethical Dilemmas Unfortunately, Apple falls short of effective ethical principles since there are some areas that need immediate attention.

- Ethical Dilemmas in Social Work Practice The society being the centerpiece of a civilization must have its own regulations and standards that create order and stability, governed by morals and obligations.

- Personal Ethical Dilemma: Adidas Case Study Business ethics considers ethical and moral principles in the context of the business environment and governs the actions and behavior of individuals in an organization.

- Parole Office’s Work Environment and Ethical Dilemma The parole officer has professionally entitled the right to disclose certain information as they regard potentially helpful in protecting and restoring the client’s health.

- Ethical Dilemmas in Psychology Forensic psychologists face numerous ethical dilemmas as they write reports and testimonies related to therapeutic interventions or evaluations in court proceedings.

- Ethical Dilemma in “Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room” “Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room” documentary resolves the ethical dilemma by identifying the infringements on morality that occurred and depicting the contributing factors.

- Circumcision Ethical Dilemma and Nurse’s Role in It Circumcision is regarded as a cultural, traditional, or medical indicator. As a rule, the expediency of circumcision causes the most heated discussions.

- Ethical Dilemma of Privacy in Technology The paper argues legal and ethical implications of new technology necessitate new ethical guidelines regarding individuals’ privacy developments.

- Organizational Ethical Dilemmas, as Portrayed in “Snowden” Edward Snowden is portrayed in the 2016 film Snowden as a victim of multiple ethical issues. The problem of the whistleblower is the ethical difficulty.

- Aristotle, Mills, and Kant on Ethical Dilemmas Aristotle, Mill, and Kant provide their approaches to solving ethical dilemmas. The paper compares the three theories.

- BCBA Interview: Ethical Dilemmas and Cultural Challenges Identifying one’s biases towards other cultures and receiving training about handling a diverse client base may assist an ABA expert in becoming more culturally competent.

- Hurricane Katrina: Government Ethical Dilemmas Hurricane Katrina is a prime example of government failure. That`s why the leadership and decision-making Issues are very important at every level: local, state and federal.

- An Ethical Dilemma of a Pregnant 16-Year-Old Girl The current ethical dilemma concerns a pregnant sixteen-year-old girl who is hesitant to tell her parents about her condition.

- Case: Evaluation of Ethical Dilemmas in Microsoft During Microsoft’s antitrust trial, Microsoft hired the Association for Competitive Technology to promote the new technology. Microsoft Corporation was the main financier of ACT.

- Ethical Dilemma in the Workplace This essay will explore how the process of ethical decision making can be used to handle the case of an employee who is underperforming hence causing undue burden to other workers.

- An Ethical Dilemma in Education This paper explores an ethical dilemma with a situation that opening an opportunity to engage in unethical behavior to reap the benefits of passing a midterm exam.

- The Trolley Problem Scenarios & Ethical Dilemmas When faced with trolley problem scenarios, one’s decision will be significantly influenced by the ethical theory of utilitarianism.

- Ethical Dilemmas in Healthcare Ethics codes exist to ensure ethical decisions are made and properly discussed, but unpredictable situations can arise that require original action methodologies.

- Bias and Ethical Decision-Making in AI Systems.

- Ethical Considerations in Gene Editing Technologies.

- Privacy in the Digital Age: Balancing Surveillance and Individual Rights.

- Environmental Ethics and Climate Change.

- The Ethics of Animal Rights: Balancing Human Interests and Animal Welfare.

- The Ethical Dilemmas in Medical Decision-Making: End-of-Life Care and Assisted Suicide.

- What Is the Ethical Use of Personal Information Online?

- Income Inequality and Social Justice: Addressing Moral Concerns in Wealth Distribution.

- The Ethics of Immigration and Border Control: How to Integrate Humanitarian Concerns in National Security?

- The Moral Implications of Capital Punishment.

- How to Balance Scientific Advancements in Biomedical Research and Human Subjects’ Rights?

- Cybersecurity and Ethical Hacking.

- How Would Drug Legalization Impact the Society?

- The Ethics of Human Cloning – What Are the Moral Dimensions?

- Ethical Dilemmas in Artificial Reproductive Technologies.

- The Morality of Euthanasia: Considering the Right to Die and Medical Ethics.

- The Ethical Implications of Genetic Testing and Privacy Concerns.

- Ethical Considerations in the LGBTQ+ Movement.

- Ethical Issues in Humanitarian Aid.

- Ethical Challenges in Big Data and Data Analytics: User Privacy and Data Security.

- The Morality of Cultural Appropriation: Respect for Cultural Traditions and Expression.

- The Ethics of Autonomous Vehicles: Moral Decision-Making in Self-Driving Cars.

- What Are the Ethical Dimensions of Reproductive Rights?

- The Ethics of Animal Testing in Cosmetic and Medical Research.

- Ethical Concerns in Artificial Womb Technology: The Future of Reproductive Ethics.

- Ethical Dilemma of Reporting Teacher Misconduct A teacher faces an ethical dilemma of whether to report her colleague on her conduct in relation to a student who has a mental disability.

- Social Worker’s Ethical Dilemma of Confidentiality The patient’s family face communication difficulties after her brain injury. The social worker has no rights to talk about the patient’s case even to her relatives.

- Ethical Dilemma: Consenting to Chemotherapy This paper explores the ethical dilemma of a minor child’s decision to undergo chemotherapy using the example of 17-year-old Kassandra.

- Helping Others: Examining an Ethical Dilemma If you approach anyone on the street and ask them if helping others is a good thing to do, the answer would most likely be “Yes.”

- Abortion: An Ethical Dilemma There are many reasons as to why abortion poses an ethical dilemma for most women. Reasons such as religious beliefs, medical concerns are easily resolved by reason and need.

- Blue Bell Ethical Dilemma Case The Blue Bell ethical case was challenging as the president faced difficult choices since the company was top-selling in the ice cream industry.

- Sexual Abuse: Researching of Ethical Dilemma The ethical dilemma chosen revolves around the social worker dealing with a situation involving a 21-year-old female client who her father had sexually molested.

- Ethical Dilemma and Decision-Making Steps Social workers are often presented with ethical dilemmas in their duties that demand competence in the ethical decision-making processes.

- Ethical Dilemmas in Public Health The public health sector must acquaint itself with the ethical principles that govern the public sector as well as the complexities that surround them.

- Ethical Dilemma in Palliative Care Nursing Modern changes necessitate the act of addressing ethical concerns that can match with the foundation of palliative medicine care practices.

- Solving Ethical Dilemmas The main principles of responsible behavior with children are reflected in The NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct. It sets the ground for solving the essential ethical dilemmas.

- Ethical Dilemmas in Education Ethical dilemmas in education occur in many cases; one of the most common reasons for their generation is injustice.

- Medical Practitioner’s Work Environment and Ethical Dilemma The ethical dilemma of a medical practitioner is to reveal patient information about a situation that can affect or lead to harm of another patient or lead to the safety of another patient.

- The Ethical Dilemma: Biblical Narratives & Secular Worldviews The paper states that ethical principles can help navigate difficult decisions. They should not be the sole determinant in deciding the individual’s values.

- Ethical and Legal Dilemmas in the Healthcare Case There are some ethical and legal dilemmas in this case. The first step in making decisions in difficult situations is identifying the moral issue.

- Stance on Ethical Dilemma and Patent Waiver for COVID-19 Discussions According to the speaker, truthful, and ethical person will find himself or herself in a full-blown ethical crisis at some time in their career; no one escapes it.

- Ethical Dilemmas: Key Aspects of Decision Making Exploring a real-life ethical leader, the Ethical Lens Inventory and ethical theories are crucial when addressing the sales representative’s ethical dilemma.

- Medical Gatekeeping and Related Ethical Dilemmas This paper discusses the ethical dilemmas in gatekeeping in managed healthcare systems and the lessons learned when it is included in other domains.

- Ethical Dilemma of Client Privacy Breach The case entails an ethical dilemma related to the appropriateness of a therapist’s breach of privacy and confidentiality when deciding the client’s best interest.

- A Pig Heart Transplant for a Person: An Ethical Dilemma The David Bennett ethical dilemma resulted in a number of legal repercussions for the different groups of people that were involved in the xenotransplantation.

- The Boeing Firm’s Ethical Dilemma Regarding the Airbus-Neo The Boeing 737-MAX airplane model was revealed nine months after the Airbus-NEO design. After the sales of the new model, two planes crashed in 2018 and 2019.

- Euthanasia as a Medical Ethical Dilemma The aim of the work is to analyze the ethical problem of medicine, such as euthanasia, and consider it as an example of a specific situation.

- Diversity at the Workplace: Ethical Dilemma Ethical dilemmas at the workplace involving racism must address the essence of diversity and God’s appreciation for the differences inherent amongst all people.

- Solving Ethical Dilemma of Discrimination This paper discusses one of the frequent ethical dilemmas in workplaces, which is discrimination, based on religion, gender, ethnicity, or nationality.

- Ethical Dilemmas, Kant’s Moral Theory, and Virtue Ethics Virtue ethics would not support the decision of breaking the contract on the grounds of loyalty. The concepts of holding to one’s word are at play here.

- Strategies to Cope with Ethical Dilemmas The navy can help individuals cope with ethical dilemmas they will encounter through cultural and historical training.

- Analysis of the Situations Wherein Ethical Dilemma Is Encountered

- The Ethical Dilemma Surrounding the Second World War

- Ethical Dilemma Working With HIV Positive Client

- Analysis of the Ethical Dilemma of Forensic Psychiatric Expertise

- Ethical Dilemma and Medical Technology

- The Ethical Dilemma Associated With Vaccinations

- Inmates and Organ Transplants: An Ethical Dilemma

- Ethical Dilemma With the End of Life Decisions

- New Zealand’s Largest Ethical Dilemma

- Ethical Dilemma: Treatment and Jehovah’s Witnesses

- The Ethical Dilemma Faced by the Managers at the Law Firm

- Review of the Ethical Dilemma of Medical Institutions

- Money Over Mind: Ethical Dilemma in Schools

- Global Warming and Its Ethical Dilemma Assignment

- Personal Ethical Dilemma for Diverse Patients

- Ethical Dilemma Analysis: Consequentialist, Deontological, and Virtue Ethics Approach

- Review the Ethical Dilemma of Medical Errors

- Ethical Dilemma for Mental Health Professionals

- What Is the Ethical Dilemma of Forensic Psychologists?

- Ethical Dilemma Surrounding Nazi Human Experimentation

- Ethical Dilemmas in Software Engineering: Volkswagen Ethical Dilemma The Volkswagen controversy is a portrayal of how engineers have compromised the company, stakeholder satisfaction, and regulatory norms by engaging in unethical behavior.

- Ethical Dilemmas in Criminal Justice System It is appropriate to apply different penalties to people because of differences in age and prior offenses in the case at hand.

- Ethical Dilemma: Case Study of Harry and Dora The situation presented in the case study between Harry and Dora is a classic scenario between the letter and the spirit of the law.

- Ethical Dilemma of Patient’s Disease Awareness The ethical dilemma in the case study may be defined as a conflict between a professional algorithm and an ambiguous request from the patient’s family members.

- Ethical Dilemma: Autonomy and End-of-Life Care The idea of providing someone with high-quality care involves the concept of respect and acceptance of the patient’s wishes.

- Researching of Ethical Dilemma in the Company Policies Moral dilemma is defined as a situation where the person is faced with multiple choices, all of which are undesirable as defined by the person.

- Ethical Dilemma Within a Clinical Organization This essay discusses in detail one of the most pressing problems of the current agenda, namely patient confidentiality as an object of health care delivery.

- The Discussion and Solution of COVID-19 Ethical Dilemma The ethical issue during the COVID-19 pandemic is related to the duties of physicians and their rights, scarce resources management, and deficit of personal protective equipment.

- Nursing Ethical Dilemmas – Balancing Morality and Practice Nursing is a very delicate profession, almost every day nurses have to deal with ethical dilemmas, which require prompt decisions.

- Finding Solutions for Ethical Dilemma The ethical dilemma that Mr. Markham is currently facing is the necessity to choose between the two undesirable options.

- Lockdown Ethical Dilemma Lockdown measures are practiced in many regions. Whether lockdown is ethical is a matter of great concern, which has sparked great debate in most countries.

- Ethical Dilemmas Faced by Oncology Nurses The paper discusses the quality of care including patients’ privacy and relates to the ethical concerns in nursing practice.

- Interpersonal Relations: One Cent Ethical Dilemma In the modern socio political environment, ethical guidelines might change over time. Therefore, it is vital to ensure that ethics training is relatable and based on current issues

- Ethical Dilemma: Euthanasia The present paper compares the Christian worldview to own worldview assumptions of euthanasia.

- Current Ethical Dilemma: HIV and AIDS in Africa The New Hock Times newspaper published on May 14, 2010, was about the rising percentages of people suffering from Aids in South Africa.

- Drug Release: Ethical Dilemma in Pharmaceutics A moral issue has emerged as to whether a pharmaceutical company has to release a new drug or not. This drug is thought to be an effective treatment of depression.

- Ethical Dilemmas in Nursing Practice: Dealing With HIV & AIDS Patients When one is faced with an ethical dilemma, making decisions between two conflicting options should be done with care.

- Ethical Dilemma: Justifying a Right to Die This essay presents a discourse on the ethical dilemma of whether there are circumstances that justify one to have a right to die.

- Ethical Dilemma: Should Gene Editing be Performed on Human Embryos? The compelling relevance of a new gene-editing technique, CRISPR has elicited debates on the modification of human genomes to eliminate genes that cause certain disorders.

- Ethical Dilemma: Eight Key Questions (8KQ) Ethics is one of the core components of human society as it regulates relations between individuals and protects them from undesired outcomes.

- Ethical Dilemmas in Business: Plumpy’nut Controversy The paper is written against this background of business activities and ethical considerations. In this paper, a case study depicting a conventional ethical dilemma is illustrated.

- “Leadership Styles of Nurse Managers in Ethical Dilemmas” by Zydziunaite This paper is a critique of the article, “Leadership styles of nurse managers in ethical dilemmas: Reasons and consequences,” whose authors are Zydziunaite and Suominen.

- Ethical Dilemmas in Business The ethical dilemma is concerned with the issue of teamwork and could be described as ambiguity in managers’ attitudes towards a team of employees.

- Eggs and Salmonella as Ethical Dilemma in Community Eggs and the threat to get sick because of salmonella bacteria should make people think about the outcomes of their decisions and the possibilities to overcome negative results.

- Colorado Alternative Products and the Ethical Dilemma Working capital management is an essential contributor to the company’s growth and profitability, and resolving an ethical dilemma needs a careful assessment of both alternatives.

- “Ethical Dilemmas in Nursing” by Rainer The ethical dilemmas that a nurse may face are varied, and understanding the core concepts behind them will help the nurse find solutions to these issues.

- A Decision to Report a Coworker’s Unethical Behavior at Work.

- Choosing Between Honesty and Protecting a Friend’s Secret.

- Deciding Whether to Speak up Against Discrimination or Harassment in the Workplace.

- An Ethical Dilemma Related to Academic Integrity and Cheating.

- A Conflict Between Personal Values and Professional Responsibilities.

- Balancing Family Obligations with Work Commitments.

- An Ethical Dilemma Concerning the Treatment of Animals and Animal Rights.

- Choosing Between Two Job Opportunities with Different Ethical Implications.

- A Decision about Whether to Donate a Substantial Portion of Income to Charity.

- A Personal Ethical Dilemma Related to Environmental Conservation and Sustainability.

- The Decision to Confront or Ignore a Friend’s Problematic Behavior.

- An Ethical Dilemma Involving Privacy and The Use of Social Media.

- Deciding Whether to Support a Controversial Political Movement.

- A Moral Dilemma Related to Medical Treatment Choices for Oneself or a Loved One.

- Choosing Between Personal Happiness and Societal Expectations.

- An Ethical Dilemma Concerning Cultural Appropriation and Respecting Other Cultures.

- Deciding Whether to Maintain a Friendship with Someone Who Holds Offensive Views.

- A Conflict Between Loyalty to Family and Individual Aspirations.

- Balancing the Need for Self-Care with Responsibilities to Others.

- An Ethical Dilemma Related to the Use of Personal Data by Technology Companies.

- Choosing Between the Truth and Protecting Someone from Getting Hurt.

- A Decision About Whether to Report a Crime Witnessed but Not Directly Involved in.

- A Personal Ethical Dilemma Involving a Financial Decision with Potential Consequences for Others.

- Deciding Whether to Intervene in a Situation of Bullying or Harassment.

- An Ethical Dilemma Related to the Disclosure of a Mental Health Condition in a Professional Setting.

- Choosing Between Personal Beliefs and Religious Expectations.

- A Conflict Between Personal Ambition and the Impact on Others.

- An Ethical Dilemma Involving the Use of Performance-Enhancing Drugs in Sports.

- Deciding Whether to Confront or Disengage from a Toxic Friendship or Relationship.

- A Personal Ethical Dilemma Related to the Treatment of Coworkers in a Leadership Position.

- Ethical Dilemma in Nursing An Ethical Nursing Practice is a decision-making challenge between two potential normative choices, neither of which is undoubtedly desirable to a nurse.

- Death With Dignity: Ethical Dilemma Brittany Maynard had an aggressive form of brain cancer, and to preserve her control over her life, she decided to move to the state that authorized the Death with Dignity Act.

- Ethical Dilemma: Regained Custody Through Legal Action The dilemma discussed in the present paper deals with a married couple addicted to drugs in the past and rehabilitated later.

- Ethical Dilemma of Worldwide Gender Equality One of the most significant issues in the context of the 21st century, however, is the ethical dilemma of worldwide gender equality.

- Ethical Dilemmas as an Integral Part of Business Ethical dilemmas are ubiquitous and knowing how to make favorable decisions is critical in the contemporary business environment.

- Oil Extraction as an Ethical Dilemma Nowadays, oil extraction and exportation has become a significant factor for the wealth of the world community and the economic situation of a particular petroleum-exporting nation.

- “A Modest Proposal” by Jonathan Swift: Ethical Dilemma “A Modest Proposal” is a film that unveils the poverty situation in Ireland. The movie’s setting was at a time when the population was increasing at a higher rate than the economy.

- Nazi March Permission: The Ethical Dilemma The decision to deny the Nazis permission was informed by three key arguments. The Nazis do not deserve the permit to march in a particular neighborhood.

- Harry Truman’s Ethical Dilemma in Dropping the Second Atom Bomb on Japan The aim of Truman dropping the second bomb on Japan was to show them the need to surrender from fighting because if they did not stop they will face more deaths and suffering.

- Sale of Human Organs in the U.S: Ethical and Legal Dilemmas This essay examines the pros and cons of the issue of sale of human organs in the US through the legal, ethical, moral prisms and its interaction with individual freedoms to finally affirm the case for the motion.

- Ethical Principles as Applied to an Ethical Dilemma (Medication Compliance) The paper discusses the four principles of nursing profession: the principle of beneficence, the principle of nonmaleficence, the principle of justice, and the principle of respect for autonomy.

- Ethical Dilemma: Handling a Request for No Further Cancer Treatment Modern technologies can prolong a person’s life and interrupt it, and this is a person’s choice of which decision to make.

- Ethical Dilemma: How to Make a Right Decision in Nursing? The ability to make the right decisions is a crucial component of the work of specialists in different conditions, including caring for distinctive categories of the population.

- Oncology and Ethical Dilemma Treatment of malignant tumors carried out most often with the use of physically and mentally traumatic means puts different ethical tasks before the doctor.

- Ethical Dilemma of Circumcision: Nurse’s Role This paper discusses what is the role of the nurse in relations to an ethical dilemma involving circumcision, and is this a medical right or a human rights issue.

- Circumcision: Ethical Dilemma and Human Rights Circumcision is a complex phenomenon that can result in ethical dilemmas. To put it simply, circumcision consists of surgical operations on female and male genitals.

- Ethical Dilemma in Facing Death Situations The purpose of this essay is to answer the question: what is ethical in the situation where numerous people are facing death?

- Daily Ethical Dilemmas in Nursing Practice At some points in their careers, nurses may face serious ethical dilemmas in which there is a threat to them of losing their jobs or harming their patients.

- Ethical Dilemma Resolving: Dividing Ownership Shares Ethical issues are a common challenge related to entrepreneurial practice. This paper will address one of these problems – dividing ownership shares.

- Build & Imagine Company’s Ethical Dilemmas Apart from the need to maximize their profits, businesses face the need to be ethical. Build & Imagine, a toy-producing company, came across an ethical dilemma regarding their targeting.

- BP Company: Environmental-Based Ethical Dilemma In the last five years, the infamous deepwater horizon oil spill has generated heated debate across the globe on the sustainability of oil mining activities of the BP Company and other competitors.

- Euthanasia as a Christian Ethical Dilemma The issue of euthanasia has been quite topical over the past few years. It is viewed as inadmissible from the Christian perspective.

- Nursing Challenges: Inexperience and Ethical Dilemmas To be a professional nurse means to face numerous challenges that arise from the nature of the given occupation.

- Ethical Dilemmas and Religious Beliefs in Healthcare For a patient, a blood transfusion is prescribed as emergent treatment. His parents do not accept the suggested treatment. So the ethical dilemma appears.

- Employee Conflicts Resolution and Ethical Dilemmas Any workplace is an environment in which many people have to interact with each other; as a result, there is a possibility of conflicts between employees.

- Medical Intervention: Ethical, Legal, and Moral Dilemmas The main ethical task of a nurse who knows about the patient’s plans to commit suicide is to prevent the realization of the client’s intentions.

- Ethical Dilemmas in Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” Hamlet is William Shakespeare’s tragedy play that was written in the late 14th century. The imagery in this play is both entertaining and creative.

- Ethical, Legal, and Moral Dilemmas in Nursing The nurse may be faced with challenge of deciding whether to respect the autonomy of patient or report to relevant authorities about the intention of patient to end own life.

- Ethical, Legal, Moral Dilemmas of Terminal Illness The moral behavior of nurses has often been described as grounded in commitment to, and receptivity for, the experience of patients, and directed towards alleviating suffering.

- Applying Ethical Frameworks: Solution of the Ethical Dilemma and Its Justification This paper attempt to provide a solution to the case study involving a work-based ethical dilemma and the justifications involved in coming up with the proposed solution.

- What Are the Sources of the Factors Which Created the Ethical Dilemma?

- How Do You Handle an Ethical Dilemma?

- What Is the Most Common Ethical Dilemma?

- How Do Ethical Dilemmas Arise and How Can They Be Solved?

- Why Is an Ethical Dilemma a Challenge in Decision-Making?

- What Causes an Ethical Dilemma in Conducting Business?

- Why Is It Important to Respond to Ethical Dilemmas?

- Is Cloning Animals Ethical Debate?

- How Do Ethical Dilemmas Arise in Healthcare?

- What Is the Impact of Ethical Dilemma?

- How to Handle Ethical Dilemmas in the Workplace?

- What Are the Characteristics of an Ethical Dilemma?

- Are There Approaches to Solving Ethical Dilemmas?

- What Are Different Types of Ethical Dilemmas That Could Occur in the Workplace?

- Is Time Management an Ethical Dilemma?

- What Are the Main Steps for Solving an Ethical Dilemma?

- How Are Ethical Debates Structured?

- What Is an Environmental Ethical Dilemma?

- Are There Ethical Debates of Cloning Today?

- What Are Some Key Ethical Dilemmas Facing Healthcare Leaders in Today’s Environment?

- How Has the Ethical Debate About Assisted Suicide Changed Over Time?

- What Are the Situations in Which an Accountant Might Face a Moral or Ethical Dilemma?

- How Does Same-Sex Marriage Ethical Debate Affect Society?

- Why Is Ethical Debate Important for Society?

- Has Ethical Debate on Face Transplantation Evolved Over Time?

Cite this post

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, January 16). 209 Ethical Dilemma Topics & Moral Issues. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/ethical-dilemma-essay-topics/

"209 Ethical Dilemma Topics & Moral Issues." StudyCorgi , 16 Jan. 2022, studycorgi.com/ideas/ethical-dilemma-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) '209 Ethical Dilemma Topics & Moral Issues'. 16 January.

1. StudyCorgi . "209 Ethical Dilemma Topics & Moral Issues." January 16, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/ethical-dilemma-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "209 Ethical Dilemma Topics & Moral Issues." January 16, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/ethical-dilemma-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "209 Ethical Dilemma Topics & Moral Issues." January 16, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/ethical-dilemma-essay-topics/.

These essay examples and topics on Ethical Dilemma were carefully selected by the StudyCorgi editorial team. They meet our highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, and fact accuracy. Please ensure you properly reference the materials if you’re using them to write your assignment.

This essay topic collection was updated on June 22, 2024 .

Home — Essay Samples — Philosophy — Ethical Dilemma — Right Vs Right Moral Dilemmas

Right Vs Right Moral Dilemmas

- Categories: Ethical Dilemma

About this sample

Words: 746 |

Published: Mar 19, 2024

Words: 746 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Philosophy

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1895 words

3 pages / 1448 words

1 pages / 412 words

1 pages / 522 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Ethical Dilemma

The development of technology is aimed at making our life easier. Whether in the medical field where advance technology may be able to detect early signs of diseases or in the automotive sector where humans can travel by car [...]

In this scenario, the primary stakeholders are the employees, which in turn affect the customers, the shareholders, the suppliers, and the community. If Roger Jacobs is allowed to remain at Shellington Pharmaceuticals and [...]

Our personal lives have been affected by the developing technology in recent years, as well as business environments, business principles, and working arrangements are influenced and shaped by these developments. With [...]

An ethical dilemma is a decision-making issue between two ethical imperatives, neither of which is unmistakably suitable or preferable (Nisenbaum, 2015). The purpose of this report is to indicate the ethical issues confronted by [...]

Ethical dilemma is a decision between two alternatives, both of which will bring an antagonistic outcome in light of society and individual rules. It is a basic leadership issue between two conceivable good objectives, neither [...]

“Rules and criteria for ethical judgement are all very well, but when conflicts are finely balanced, we simply express our preferences.”The concept of moral justification in ethics examples has been a topic of discussion for [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Moral Dilemmas

Moral dilemmas, at the very least, involve conflicts between moral requirements. Consider the cases given below.

1. Examples

2. the concept of moral dilemmas, 3. problems, 4. dilemmas and consistency, 5. responses to the arguments, 6. moral residue and dilemmas, 7. types of moral dilemmas, 8. conclusion, cited works, other worthwhile readings, other internet resources, related entries.

In Book I of Plato's Republic , Cephalus defines ‘justice’ as speaking the truth and paying one's debts. Socrates quickly refutes this account by suggesting that it would be wrong to repay certain debts — for example, to return a borrowed weapon to a friend who is not in his right mind. Socrates' point is not that repaying debts is without moral import; rather, he wants to show that it is not always right to repay one's debts, at least not exactly when the one to whom the debt is owed demands repayment. What we have here is a conflict between two moral norms: repaying one's debts and protecting others from harm. And in this case, Socrates maintains that protecting others from harm is the norm that takes priority.

Nearly twenty-four centuries later, Jean-Paul Sartre described a moral conflict the resolution of which was, to many, less obvious than the resolution to the Platonic conflict. Sartre [1957] tells of a student whose brother had been killed in the German offensive of 1940. The student wanted to avenge his brother and to fight forces that he regarded as evil. But the student's mother was living with him, and he was her one consolation in life. The student believed that he had conflicting obligations. Sartre describes him as being torn between two kinds of morality: one of limited scope but certain efficacy, personal devotion to his mother; the other of much wider scope but uncertain efficacy, attempting to contribute to the defeat of an unjust aggressor.

While the examples from Plato and Sartre are the ones most commonly cited, it should be clear that there are many others. If a person makes conflicting promises, she faces a moral conflict. Physicians and families who believe that human life should not be deliberately shortened and that unpreventable pain should not be tolerated face a conflict in deciding whether to withdraw life support from a dying patient.

What is common to the two well-known cases is conflict. In each case, an agent regards herself as having moral reasons to do each of two actions, but doing both actions is not possible. Ethicists have called situations like these moral dilemmas . The crucial features of a moral dilemma are these: the agent is required to do each of two (or more) actions; the agent can do each of the actions; but the agent cannot do both (or all) of the actions. The agent thus seems condemned to moral failure; no matter what she does, she will do something wrong (or fail to do something that she ought to do).

The Platonic case strikes many as too easy to be characterized as a genuine moral dilemma. For the agent's solution in that case is clear; it is more important to protect people from harm than to return a borrowed weapon. And in any case, the borrowed item can be returned later, when the owner no longer poses a threat to others. Thus in this case we can say that the requirement to protect others from serious harm overrides the requirement to repay one's debts by returning a borrowed item when its owner so demands. When one of the conflicting requirements overrides the other, we do not have a genuine moral dilemma. So in addition to the features mentioned above, in order to have a genuine moral dilemma it must also be true that neither of the conflicting requirements is overridden [Sinnott-Armstrong (1988), Chapter 1].

It is less obvious in Sartre's case that one of the requirements overrides the other. Why this is so, however, may not be so obvious. Some will say that our uncertainty about what to do in this case is simply the result of uncertainty about the consequences. If we were certain that the student could make a difference in defeating the Germans, the obligation to join the military would prevail. But if the student made little difference whatsoever in that cause, then his obligation to tend to his mother's needs would take precedence, since there he is virtually certain to be helpful. Others, though, will say that these obligations are equally weighty, and that uncertainty about the consequences is not at issue here.

Ethicists as diverse as Kant [1971/1797], Mill [1979/1861], and Ross [1930 and 1939] have assumed that an adequate moral theory should not allow for the possibility of genuine moral dilemmas. Only recently — in the last fifty years or so — have philosophers begun to challenge that assumption. And the challenge can take at least two different forms. Some will argue that it is not possible to preclude genuine moral dilemmas. Others will argue that even if it were possible, it is not desirable to do so.

To illustrate some of the debate that occurs regarding whether it is possible for any theory to eliminate genuine moral dilemmas, consider the following. The conflicts in Plato's case and in Sartre's case arose because there is more than one moral precept (using ‘precept’ to designate rules and principles), more than one precept sometimes applies to the same situation, and in some of these cases the precepts demand conflicting actions. One obvious solution here would be to arrange the precepts, however many there might be, hierarchically. By this scheme, the highest ordered precept always prevails, the second prevails unless it conflicts with the first, and so on. There are at least two glaring problems with this obvious solution, however. First, it just does not seem credible to hold that moral rules and principles should be hierarchically ordered. While the requirements to keep one's promises and to prevent harm to others clearly can conflict, it is far from clear that one of these requirements should always prevail over the other. In the Platonic case, the obligation to prevent harm is clearly stronger. But there can easily be cases where the harm that can be prevented is relatively mild and the promise that is to be kept is very important. And most other pairs of precepts are like this. This was a point made by Ross in The Right and the Good [1930, Chapter 2].

The second problem with this easy solution is deeper. Even if it were plausible to arrange moral precepts hierarchically, situations can arise in which the same precept gives rise to conflicting obligations. Perhaps the most widely discussed case of this sort is taken from William Styron's Sophie's Choice [1980] [Greenspan (1983)]. Sophie and her two children are at a Nazi concentration camp. A guard confronts Sophie and tells her that one of her children will be allowed to live and one will be killed. But it is Sophie who must decide which child will be killed. Sophie can prevent the death of either of her children, but only by condemning the other to be killed. The guard makes the situation even more excruciating by informing Sophie that if she chooses neither, then both will be killed. With this added factor, Sophie has a morally compelling reason to choose one of her children. But for each child, Sophie has an apparently equally strong reason to save him or her. Thus the same moral precept gives rise to conflicting obligations. Some have called such cases symmetrical [Sinnott-Armstrong (1988), Chapter 2].

We shall return to the issue of whether it is possible to preclude genuine moral dilemmas. But what about the desirability of doing so? Why have ethicists thought that their theories should preclude the possibility of dilemmas? At the intuitive level, the existence of moral dilemmas suggests some sort of inconsistency. An agent caught in a genuine dilemma is required to do each of two acts but cannot do both. And since he cannot do both, not doing one is a condition of doing the other. Thus, it seems that the same act is both required and forbidden. But exposing a logical inconsistency takes some work; for initial inspection reveals that the inconsistency intuitively felt is not present. Allowing OA to designate that the agent in question ought to do A (or is morally obligated to do A , or is morally required to do A ), that OA and OB are both true is not itself inconsistent, even if one adds that it is not possible for the agent to do both A and B . And even if the situation is appropriately described as OA and O ¬ A , that is not a contradiction; the contradictory of OA is ¬ OA . [See Marcus (1980).]

Similarly rules that generate moral dilemmas are not inconsistent, at least on the usual understanding of that term. Ruth Marcus suggests plausibly that we “define a set of rules as consistent if there is some possible world in which they are all obeyable in all circumstances in that world.” Thus, “rules are consistent if there are possible circumstances in which no conflict will emerge,” and “a set of rules is inconsistent if there are no circumstances, no possible world, in which all the rules are satisfiable” [Marcus (1980), p. 128 and p. 129]. I suspect that Kant, Mill, and Ross were aware that a dilemma-generating theory need not be inconsistent. Even so, they would be disturbed if their own theories allowed for such predicaments. If I am correct in this speculation, it suggests that Kant, Mill, Ross, and others thought that there is an important theoretical feature that dilemma-generating theories lack. And this is understandable. It is certainly no comfort to an agent facing a reputed moral dilemma to be told that at least the rules which generate this predicament are consistent. For a good practical example, consider the situation of the criminal defense attorney. She is said to have an obligation to hold in confidence the disclosures made by a client and to be required to conduct herself with candor before the court (where the latter requires that the attorney inform the court when her client commits perjury) [Freedman (1975), Chapter 3]. It is clear that in this world these two obligations often conflict. It is equally clear that in some possible world — for example, one in which clients do not commit perjury — that both obligations can be satisfied. Knowing this is of no assistance to defense attorneys who face a conflict between these two requirements in this world.

Ethicists who are concerned that their theories not allow for moral dilemmas have more than consistency in mind, I think. What is troubling is that theories that allow for dilemmas fail to be uniquely action-guiding . A theory can fail to be uniquely action-guiding in either of two ways: by not recommending any action in a situation that is moral or by recommending incompatible actions. Theories that generate genuine moral dilemmas fail to be uniquely action-guiding in the latter way. Since at least one of the main points of moral theories is to provide agents with guidance, that suggests that it is desirable for theories to eliminate dilemmas, at least if doing so is possible.

But failing to be uniquely action-guiding is not the only reason that the existence of moral dilemmas is thought to be troublesome. Just as important, the existence of dilemmas does lead to inconsistencies if one endorses certain widely held theses. Here we shall consider two different arguments, each of which shows that one cannot consistently acknowledge the reality of moral dilemmas while holding selected principles.

The first argument shows that two standard principles of deontic logic are, when conjoined, incompatible with the existence of moral dilemmas. The first of these is the principle of deontic consistency

Principle of Deontic Consistency ( PC ): OA → ¬ O ¬ A .

Intuitively this principle just says that the same action cannot be both obligatory and forbidden. Note that as initially described, the existence of dilemmas does not conflict with PC. For as described, dilemmas involve a situation in which an agent ought to do A , ought to do B , but cannot do both A and B . But if we add a principle of deontic logic, then we obtain a conflict with PC:

Principle of Deontic Logic ( PD ): □ ( A → B ) → ( OA → OB ).

Intuitively, PD just says that if doing A brings about B , and if A is obligatory (morally required), then B is obligatory (morally required). The first argument that generates inconsistency can now be stated. Premises (1), (2), and (3) represent the claim that moral dilemmas exist.

| (1) | ||

| (2) | ||

| (3) | ¬ ( & | [where ‘¬ ’ means ‘cannot’] |

| (4) | □ ( → ) → ( → ) | [where ‘□’ means physical necessity] |

| (5) | □ ¬ ( & ) | (from 3) |

| (6) | □ ( → ¬ ) | (from 5) |

| (7) | □ ( → ¬ ) → ( → ¬ ) | (an instantiation of 4) |

| (8) | → ¬ | (from 6 and 7) |

| (9) | ¬ | (from 2 and 8) |

| (10) | and ¬ | (from 1 and 9) |

Line (10) directly conflicts with PC. And from PC and (1), we can conclude

(11) ¬ O ¬ A

And, of course, (9) and (11) are contradictory. So if we assume PC and PD, then the existence of dilemmas generates an inconsistency of the old-fashioned logical sort. [Note: In standard deontic logic, the ‘□’ in PD typically designates logical necessity. Here I take it to indicate physical necessity so that the appropriate connection with premise (3) can be made. And I take it that logical necessity is stronger than physical necessity.]

Two other principles accepted in most systems of deontic logic entail PC. So if PD holds, then one of these additional two principles must be jettisoned too. The first says that if an action is obligatory, it is also permissible. The second says that an action is permissible if and only if it is not forbidden. These principles may be stated as:

(OP): OA → PA ;

(D): PA ↔ ¬ O ¬ A .

The second argument that generates inconsistency, like the first, has as its first three premises a symbolic representation of a moral dilemma.

(1) OA (2) OB (3) ¬ C ( A & B )

And like the first, this second argument shows that the existence of dilemmas leads to a contradiction if we assume two other commonly accepted principles. The first of these principles is that ‘ought’ implies ‘can’. Intuitively this says that if an agent is morally required to do an action, it must be possible for the agent to do it. We may represent this as

(4) OA → CA (for all A )

The other principle, endorsed by most systems of deontic logic, says that if an agent is required to do each of two actions, she is required to do both. We may represent this as

(5) ( OA & OB ) → O ( A & B )

The argument then proceeds:

(6) O ( A & B ) → C ( A & B ) (an instance of 4) (7) OA & OB (from 1 and 2) (8) O ( A & B ) (from 5 and 7) (9) ¬ O ( A & B ) (from 3 and 6)

So if one assumes that ‘ought’ implies ‘can’ and if one assumes the principle represented in (5) — dubbed by some the agglomeration principle [Williams (1965)] — then again a contradiction can be derived.

Now obviously the inconsistency in the first argument can be avoided if one denies either PC or PD. And the inconsistency in the second argument can be averted if one gives up either the principle that ‘ought’ implies ‘can’ or the agglomeration principle. There is, of course, another way to avoid these inconsistencies: deny the possibility of genuine moral dilemmas. It is fair to say that much of the debate concerning moral dilemmas in the last fifty years has been about how to avoid the inconsistencies generated by the two arguments above.

Opponents of moral dilemmas have generally held that the crucial principles in the two arguments above are conceptually true, and therefore we must deny the possibility of genuine dilemmas. [See, for example, Conee (1982) and Zimmerman (1996).] Most of the debate, from all sides, has focused on the second argument. There is an oddity about this, however. When one examines the pertinent principles in each argument which, in combination with dilemmas, generates an inconsistency, there is little doubt that those in the first argument have a greater claim to being conceptually true than those in the second. Perhaps the focus on the second argument is due to the impact of Bernard Williams's influential essay [Williams (1965)]. But notice that the first argument shows that if there are genuine dilemmas, then either PC or PD must be relinquished. Even most supporters of dilemmas acknowledge that PC is quite basic. E.J. Lemmon, for example, notes that if PC does not hold in a system of deontic logic, then all that remains are truisms and paradoxes [Lemmon (1965), p. 51]. And giving up PC also requires denying either OP or D, each of which also seems basic. There has been much debate about PD — in particular, questions generated by the Good Samaritan paradox — but still it seems basic. So those who want to argue against dilemmas purely on conceptual grounds are better off focusing on the first of the two arguments above.

Some opponents of dilemmas also hold that the pertinent principles in the second argument — the principle that ‘ought’ implies ‘can’ and the agglomeration principle — are conceptually true. But foes of dilemmas need not say this. Even if they believe that a conceptual argument against dilemmas can be made by appealing to PC and PD, they have several options regarding the second argument. They may defend ‘ought’ implies ‘can’, but hold that it is a substantive normative principle, not a conceptual truth. Or they may even deny the truth of ‘ought’ implies ‘can’ or the agglomeration principle, though not because of moral dilemmas, of course.

Defenders of dilemmas need not deny all of the pertinent principles, of course. If one thinks that each of the principles at least has some initial plausibility, then one will be inclined to retain as many as possible. Among the earlier contributors to this debate, some took the existence of dilemmas as a counterexample to ‘ought’ implies ‘can’ [for example, Lemmon (1962) and Trigg (1971)]; others, as a refutation of the agglomeration principle [for example, Williams (1965) and van Fraassen (1973)]. The most common response to the first argument was to deny PD.

Friends and foes of dilemmas have a burden to bear in responding to the two arguments above. For there is at a prima facie plausibility to the claim that there are moral dilemmas and to the claim that the relevant principles in the two arguments are true. Thus each side must at least give reasons for denying the pertinent claims in question. Opponents of dilemmas must say something in response to the positive arguments that are given for the reality of such conflicts. One reason in support of dilemmas, as noted above, is simply pointing to examples. The case of Sartre's student and that from Sophie's Choice are good ones; and clearly these can be multiplied indefinitely. It will tempting for supporters of dilemmas to say to opponents, “If this is not a real dilemma, then tell me what the agent ought to do and why ?” It is obvious, however, that attempting to answer such questions is fruitless, and for at least two reasons. First, any answer given to the question is likely to be controversial, certainly not always convincing. And second, this is a game that will never end; example after example can be produced. The more appropriate response on the part of foes of dilemmas is to deny that they need to answer the question. Examples as such cannot establish the reality of dilemmas. Surely most will acknowledge that there are situations in which an agent does not know what he ought to do. This may be because of factual uncertainty, uncertainty about the consequences, uncertainty about what principles apply, or a host of other things. So for any given case, the mere fact that one does not know which of two (or more) conflicting obligations prevails does not show that none does.

Another reason in support of dilemmas to which opponents must respond is the point about symmetry. As the cases from Plato and Sartre show, moral rules can conflict. But opponents of dilemmas can argue that in such cases one rule overrides the other. Most will grant this in the Platonic case, and opponents of dilemmas will try to extend this point to all cases. But the hardest case for opponents is the symmetrical one, where the same precept generates the conflicting requirements. The case from Sophie's Choice is of this sort. It makes no sense to say that a rule or principle overrides itself. So what do opponents of dilemmas say here? They are apt to argue that the pertinent, all-things-considered requirement in such a case is disjunctive: Sophie should act to save one or the other of her children, since that is the best that she can do [for example, Zimmerman (1996), Chapter 7]. Such a move need not be ad hoc , since in many cases it is quite natural. If an agent can afford to make a meaningful contribution to only one charity, the fact that there are several worthwhile candidates does not prompt many to say that the agent will fail morally no matter what he does. Nearly all of us think that he should give to one or the other of the worthy candidates. Similarly, if two people are drowning and an agent is situated so that she can save either of the two but only one, few say that she is doing wrong no matter which she saves. Positing a disjunctive requirement in these cases seems perfectly natural, and so such a move is available to opponents of dilemmas as a response to symmetrical cases.

Supporters of dilemmas have a burden to bear too. They need to cast doubt on the adequacy of the pertinent principles in the two arguments that generate inconsistencies. And most importantly, they need to provide independent reasons for doubting whichever of the principles they reject. If they have no reason other than cases of putative dilemmas for denying the principles in question, then we have a mere standoff. Of the principles in question, the most commonly questioned on independent grounds are the principle that ‘ought’ implies ‘can’ and PD. Among supporters of dilemmas, Walter Sinnott-Armstrong [Sinnott-Armstrong (1988), Chapters 4 and 5] has gone to the greatest lengths to provide independent reasons for questioning some of the relevant principles.

One well-known argument for the reality of moral dilemmas has not been discussed yet. This argument might be called “phenomenological.” It appeals to the emotions that agents facing conflicts experience and our assessment of those emotions.