Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Home Grown Terrorism in The United States (US) – Causes, Affiliations and Policy Implications

In the wake of the September 11th, 2001 attacks of the twin towers in New York and the Pentagon in Washington D.C, a focus on decapitating and dislodging transnational terrorist groups from safe heavens overseas have shifted research and policy efforts from threats of potential homegrown terror activities. The paper explores causes of home grown terrorism, the role of transnational terror groups and policy implications on effective counter-terrorism in the United States of America while carefully examining the May, 2010 attempted attack of Time Square, New York and April 2013 Boston Marathon Bombings as case studies for analysis.

Related Papers

Zachary Maragia

Terrorism and Political Violence

Joshua D. Freilich

Klisman Murati

A sense of morbid paranoia has engulfed the Western establishment following the acts of 9/11 and consecutive terror acts in Europe, and although it may be easy to conceptualise them in all the same way there are very distinct differences that separate them. This paper explores an innovation in terrorist strategy titled home-grown terrorism, a reincarnation of guerrilla warfare for the modern day freedom fighter. We tackle the established academic paradigm that HGT is synonymous with Islamic radicalization and provide an innovative approach to understanding this new phenomenon that takes Islam out of the heart of this debate and replaces it with credible alternatives that strike at the core of terrorist motivations. Building on the research design of Bakker (2006) we design a global replica that tests our new hypothesis and provides a platform for further original research.

Security Journal

Larry Gaines

tony lemieux , M. Beasley , William (Bill) Harlow , James Lutz

Aaron Winter

At 9:02 on the morning of April 19th, 1995, a bomb went off at the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. The bomb not only killed over 160 people and injured more than 650, but it also shook the illusion held by many Americans of a nation safe from the political unrest and terrorism outside its borders (an illusion that would be shattered for good on 9/11). In the hours and days following the bombing, the media and law enforcement authorities focused on the Muslim terrorists they believed were responsible, including a Muslim Oklahoma City resident detained at Heathrow Airport in London. On April 20th, one day after bombing, another Oklahoma City resident, Iraqi refugee Suhair al-Mosawi, was attacked in his home as retaliation for the bombing. When Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols – two white, Christian, home-grown anti-government activists – were arrested, what became evident was that these were ‘American’ terrorists. In spite of the initial shock of the bombing and focus on Muslims, this was far from a new phenomenon. For many experts who had been researching and monitoring the extreme right, the bombing was the culmination of a fifteen-year trajectory of violence. In response to the bombing, hearings were held, anti-terror legislation was passed, arrests were made and numerous books written and films made about the phenomenon. Yet, following the events of 9/11, Oklahoma City and the domestic extreme right were pushed to the margins of history and memory, as terrorism and terrorists were redefined as Islamic or Islamist, and Christianity and patriotism were evoked in America’s defense. Throughout American history, both terrorism and extremism have been constructed, evoked or ignored strategically by the state, media and public at different points, in order to disown and demonize political movements whenever their ideologies and objectives become problematic or inconvenient – because they overlap with, and thus compromise, the legitimacy of the dominant ideology and democratic credentials of the state, because they conflict with the dominant ideology or hegemonic order, because they offend the general (voting) public, or because they expose the fallacies of national unity and bi-polar opposition in the face of foreign enemies or international conflicts, such as the war on terror. This chapter looks at how domestic extreme right terrorism has been constructed, represented, evoked or ignored in the American political imagination in the post-civil rights era, with a particular focus on its changing status following the Oklahoma City bombing and 9/11.""

The Open Psychology Journal

Alice LoCicero

Stephen Bowers

Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy

Kaisa Hinkkainen

Dr. Ben Johnson

Update of original paper September 12, 2017

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Gene R Souza

FORENSIC EXAMINER

Frank S . Perri JD, CPA, CFE

Criminology & Public Policy

Gary LaFree

Manni Crone

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE

John Maszka

Annual Review of Political …

winifred attah

Fabrizio Longarzo

Mahmoud Eid

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Home Grown: How Domestic Violence Turns Men Into Terrorists – review

Joan Smith examines the roots of terrorism, but fails to address the complexities of social inequality

K halid Masood, 52, born Adrian Russell Elms, drove across Westminster Bridge in 2017 mowing down pedestrians and stabbing to death PC Keith Palmer. He had a string of criminal convictions for offences involving violence but since 2003 he had done little to attract police attention. Instead, in Home Grown , Joan Smith argues that Masood had chosen to “privatise his aggressive behaviour, hiding it behind closed doors”, controlling and beating a succession of women.

Smith, a feminist and human rights activist, contends that if victims were believed, domestic abuse was better recognised, policed efficiently and addressed appropriately in court, then numerous acts of terrorism, committed in the name of religion, extreme ideology and misogyny, could – and can – be avoided. So why is this link ignored?

Among the examples she gives is Darren Osborne , who drove his van into a group of Muslims in London’s Finsbury Park; Saïd and Chérif Kouachi , who carried out the attack on the French satirical magazine, Charlie Hebdo ; and Salman Abedi , who detonated a homemade bomb in the foyer of the Manchester Arena with such horrific consequences. Abedi, 17, had punched a fellow female student in the head, telling her that her skirt was too short; he went unpunished, leaving no warning sign, according to Smith’s theory, which could have provided invaluable information to the security forces.

Childhood lives informed wholly or in part by misogyny, poverty, neglect, abuse and racism, Smith argues, shaped, for instance, “the Beatles”, the London gang members who joined Islamic State, the Kouachi brothers and murderous angry young white men such as 22-year-old Elliot Rodger, an “incel” , involuntary celibate. “I will destroy all women because I can never have them,” he declared in his manifesto before killing six and wounding 13 women and men in California in 2014.

Smith quotes Nazir Afzal , a solicitor and former chief crown prosecutor for the north-west of England who has been indefatigable in his pursuit of child sexual exploitation and violence against women: “The first victim of an extremist or terrorist is the woman in his own home.” He points out that 25,000 men are on the radar of police and the security services as potential terrorist threats. “You can’t monitor 25,000. But you shouldn’t have to. You already know which ones to target by flagging up violence against women as a high-risk factor.”

It’s hard to fault the logic: treat what police used to call “domestics” as the serious crime it is and you considerably improve the chances of saving the lives not only of wives, partners and former girlfriends but also members of the public. And yet there is a conundrum at the heart of Home Grown . It reads like a letter from the recent past. And while domestic abuse is a red flag, it is only part of a much more complex challenge. Smith herself asks why “… siblings from the same families grow up in equally damaging circumstances but don’t become abusers let alone terrorists”. Misogyny and terrorism don’t have to be infectious.

Domestic abuse (the reference to “violence” in the book’s title doesn’t allow for coercive control, stalking and harassment that leave no physical wounds but can inflict deep mental scars) is rife. One in five women will experience it in her lifetime. Smith has reported on the cumulative impact of misogyny and violence directed at women and girls for decades. Currently, she co-chairs the London mayor’s violence against women and girls board. In Home Grown , she writes that in the year ending March 2016, the police recorded more than 1 million domestic abuse cases in England and Wales, a fraction of the genuine extent of the crime. Systemic failures to arrest dangerous men continue; refuges are drastically underfunded. But there has been progress and paradoxically in refusing to surrender her pessimism, Smith does feminist activists and their supporters a disservice.

In the book, Smith repeatedly insists the scale and effects of domestic abuse “are played down or even denied altogether”. Attacks, she asserts, are explained away “as though violent men lack self-control and can’t help themselves”. She cites the stereotypes of women who are to blame for allegedly triggering violence – “nagging” wives. “Toxic masculinity,” she argues, “hasn’t received anything like sufficient attention.” Really? In the UK?

Forty years ago, sociologists, R Emerson Dobash and Russell Dobash published a seminal work, Violence Against Wives . “Women’s place in history has most often been at the receiving end of a blow,” they wrote. It was a time when “battered women” were deemed deviant and deserved what they got; men were believed to be innately aggressive. Domineering mothers created perpetrators who married frigid women. Nothing was a violent man’s fault. Presciently, the Dobashes discarded these dominant “theories”, challenged the patriarchy and demanded more “work on the subordination, isolation and devalued status of women in society… and change to the hierarchical family”.

If several large steps haven’t been taken in that direction, if negative female stereotypes aren’t challenged daily, if pressure isn’t constantly exerted on police and the judiciary to do more, if we now don’t have a better understanding of the impact of insecure childhoods, low self-esteem and economic stress in the makings of modern masculinity, then campaigners, #MeToo and women speaking out who have experienced abuse have made no progress at all. And they have.

In the final chapters of Home Grown , Smith offers her unsurprising recommendations, including better police training. She also acknowledges what may prove fruitful for even earlier identification of both potential abusers and terrorists. In the 1990s, research began, and continues, into adverse child experiences (Aces). Ten have been identified, including physical and emotional abuse and growing up in a household that is poor and/or with parents who have problems with drugs and/or alcohol. Four Aces flag up a vulnerable child who requires support that is sensitive to their trauma. The Scottish government, commendably, is adapting many of its policies accordingly.

Domestic abuse is rooted in inequality – that needs to be aggressively tackled but so, too, does bringing the right kind of help to boys such as the Kouachis long before they raise a hand in anger.

- Society books

- Observer book of the week

- Domestic violence

Most viewed

- DOI: 10.1080/10576100802564022

- Corpus ID: 143731420

Homegrown Jihadist Terrorism in the United States: A New and Occasional Phenomenon?

- Lorenzo Vidino

- Published 20 January 2009

- Political Science

- Studies in Conflict & Terrorism

39 Citations

Place still matters: the operational geography of jihadist terror attacks against the us homeland 1990–2012, when harry met salafi: literature review of homegrown jihadi terrorism, iraq versus lack of integration: understanding the motivations of contemporary islamist terrorists in western countries, violent radicalization in europe: what we know and what we do not know, defining and understanding the jihadi-salafi movement, radicalization within the somali-american diaspora: countering the homegrown terrorist threat, homegrown terrorism and transformative learning: an interdisciplinary approach to understanding radicalization, the politics of postsecular borders: everyday life and the ground zero mosque controversy, hold your friends close, selected literature on radicalization and de-radicalization of terrorists: monographs, edited volumes, grey literature and prime articles published since the 1960s, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

What NIJ Research Tells Us About Domestic Terrorism

Militant, nationalistic, white supremacist violent extremism has increased in the United States. In fact, the number of far-right attacks continues to outpace all other types of terrorism and domestic violent extremism. Since 1990, far-right extremists have committed far more ideologically motivated homicides than far-left or radical Islamist extremists, including 227 events that took more than 520 lives. [1] In this same period, far-left extremists committed 42 ideologically motivated attacks that took 78 lives. [2] A recent threat assessment by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security concluded that domestic violent extremists are an acute threat and highlighted a probability that COVID-19 pandemic-related stressors, long-standing ideological grievances related to immigration, and narratives surrounding electoral fraud will continue to serve as a justification for violent actions. [3]

Over the past 20 years, the body of research that examines terrorism and domestic violent extremism has grown exponentially. Studies have looked at the similarities and differences between radicalization to violent domestic ideologies and radicalization to foreign extremist ideologies. Research has found that radicalization processes and outcomes — and perhaps potential prevention and intervention points — vary by group structure and crime type. In addition, research has explored promising and effective approaches for how communities can respond to radicalization and prevent future attacks. [4]

The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) has played a unique role in the evolving literature on terrorism and violent extremism. NIJ has promoted the development of comprehensive terrorism databases to help inform criminal justice responses to terrorism, address the risk of terrorism to potential targets, examine the links between terrorism and other crimes, and study the organizational, structural, and cultural dynamics of terrorism. In 2012, the U.S. Congress requested that NIJ build on these focal points by funding “research targeted toward developing a better understanding of the domestic radicalization phenomenon and advancing evidence-based strategies for effective intervention and prevention.” [5] NIJ has since funded more than 50 research projects on domestic radicalization, which have led to a better understanding of the processes that result in violent action, factors that increase the risk of radicalizing to violence, and how best to prevent and respond to violent extremism.

This article discusses the findings of several NIJ-supported domestic radicalization studies that cover a range of individual and network-centered risk and protective factors that affect radicalization processes, including military involvement and online environments. The article also explores factors that shape the longevity of radicalization processes and their variation by group structure and crime type, and examines factors that affect pathways away from domestic extremism. It concludes with a discussion of how these findings can inform terrorism prevention strategies, criminal justice policy, and community-based prevention programming.

The Characteristics of U.S. Extremists and Individuals Who Commit Hate Crimes

Over the past two decades, research that seeks to understand individual-level engagement in violent extremism has grown tremendously. However, as the research field has developed, a gap has emerged between the increasingly sophisticated arguments that scholars use to explain extremism and the availability of data to test, refine, and validate theories of radicalization.

In 2012, NIJ funded the Empirical Assessment of Domestic Radicalization project to address the data gap in radicalization research. [6] The project created the Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States (PIRUS) database, a cross-ideological repository of information on the characteristics of U.S. extremists. In 2017, NIJ supported a follow-on project [7] that sought to replicate the PIRUS data for individuals in the United States who commit hate crimes. This project yielded the Bias Incidents and Actors Study (BIAS) dataset, the first data resource for researchers and practitioners interested in understanding the risk and protective factors associated with committing hate crimes.

PIRUS and BIAS are designed to provide users with information on a wide range of factors that can play a role in a person’s radicalization to criminal activity. [8] These risk and protective factors can be divided into four domains: [9]

- The situational characteristics of the crimes, including whether the acts were premeditated or spontaneous, involved co-conspirators, or were committed while under the influence of drugs and alcohol.

- The characteristics of the victims, including whether targets were “hard” (for example, military bases, secure facilities) or “soft” (for example, businesses, public areas, private civilians) and whether the individuals had prior relationships with their victims.

- Factors that produce the social bonds that may protect against mobilization to violence, such as marriage, military service, work experience, and advanced education.

- Factors that may act as radicalization mechanisms and risk factors for violence, such as previous criminal activity, membership in extremist or hate groups, substance use, and mental illness.

The PIRUS and BIAS data have been used to generate insights on a range of important topics related to hate crime and extremism; however, there are three overarching findings common to both datasets: diversity in beliefs, diversity in behaviors, and diversity in characteristics.

Diversity in Beliefs

Although it is not uncommon for a particular ideology to dominate the public discourse around extremism, the PIRUS and BIAS data indicate that U.S. extremists and individuals who commit hate crimes routinely come from across the ideological spectrum, including far-right, far-left, Islamist, or single-issue ideologies. These ideologies break down into particular movements, or sub-ideologies. For instance, in 2018, the PIRUS data identified extremists associated with several anti-government movements, Second Amendment militias, the sovereign citizen movement, white supremacy, ecoterrorism, anarchism, the anti-abortion movement, the QAnon conspiracy theory, and others. [10] The prevalence of particular movements can ebb and flow over time depending on political climate and law enforcement priorities, but at no point in recent U.S. history has one set of beliefs completely dominated extremism or hate crime activity. [11] Furthermore, the PIRUS and BIAS data reveal that U.S. extremists and individuals who commit hate crimes are often motivated by overlapping views. For instance, it is common for individuals from the anti-government militia movement to adopt views of white supremacy or for those from the extremist environmental movement to take part in anarchist violence. Nearly 17% of the individuals in PIRUS were affiliated with more than one extremist group or sub-ideological movement, and nearly 15% of the individuals in BIAS selected the victims of their hate crimes because of multiple identity characteristics, such as race and sexual orientation. [12]

Diversity in Behaviors

Although radicalization to violence has been a primary topic in extremism and hate crime research, the PIRUS and BIAS data indicate that U.S. extremists and individuals who commit hate crimes often engage in a range of violent and nonviolent criminal activities. Indeed, 42% of PIRUS and nearly 30% of BIAS individual actors engaged exclusively in nonviolent crimes, such as property damage, financial schemes, and illegal demonstrations. [13] Moreover, the violent outcomes represented in the PIRUS and BIAS data vary in scope and type. For instance, approximately 15% of those in BIAS committed or planned to commit mass casualty crimes, while the remaining subjects targeted specific victims. [14] Similarly, nearly 50% of those in BIAS did not premeditate their crimes but rather acted spontaneously after chance encounters with their victims. [15]

Diversity in Characteristics

One of the more common conclusions of recent research on radicalization is that no single profile accurately captures the characteristics of the individuals who commit extremist and hate crimes. [16] The PIRUS and BIAS data support this finding, revealing that background characteristics vary considerably depending on ideological affiliations. For instance, white supremacists in PIRUS tend to be older and less well-educated and are more likely to have criminal histories than those who were inspired by foreign terrorist groups, such as al-Qaida or the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or those associated with the extremist environmental or anarchist movements. [17] Despite these differences, some risk and protective factors tend to separate violent from nonviolent individuals, regardless of ideology. [18] In the PIRUS data, individuals with criminal records, documented or suspected mental illness, and membership in extremist cliques are more often classified as violent, while those who are married with stable employment backgrounds are more likely to engage in nonviolent crimes. [19] Similarly, in BIAS, violent individuals are more likely to co-offend with peers, have criminal histories that include acts of violence, and offend while under the influence of drugs or alcohol. [20]

Military Experience and Domestic Violent Extremism

According to current statistics, individuals with military backgrounds represent 11.5% of the total known extremists who have committed violent and nonviolent crimes in the United States since 1990. [21] Although this percentage seems small, there has been a growing trend of (former) military members engaging in extremist offenses in recent years. An average of seven people with U.S. military backgrounds per year committed extremist crimes between 1990 and 2010. That rate has risen to an average of 29 people per year over the past decade. Also worth noting is that more than half (52%) of extremists with military experience are identified as violent.

Given the growth of violent domestic extremism among military personnel, the relationship between military service and radicalization has become a major concern. Prior NIJ-funded studies have identified military experience as a potential risk factor for attempted and actual terrorism. [22] The likelihood of radicalization and radicalization to violence increases when individuals have already left military service. [23] This research suggests that military service is not a social bond that inhibits extremist violence.

NIJ studies have also shown that individuals with military experience may be susceptible to recruitment by domestic violent extremist groups due to their unique skills, which an extremist group may perceive as contributing to the success of a terrorist attack. [24] Also, transitioning from military to civilian life appears to be a pull factor for engaging in violent extremism. [25] Indicators for potential involvement in extremism may include a lack of a sense of community, purpose, and belonging. If these indicators are identified early, community stakeholders — in partnership with military agencies — could have an opportunity to intervene. Although such knowledge is valuable, the role of military service in radicalization to violent extremism still requires study.

Differences in Violent Extremist Characteristics Between Military Veterans and Civilians

In 2019, NIJ funded researchers at the University of Southern California to study the link between military service and violent domestic extremism. They are also examining the differences between military veteran and civilian extremists in terms of their characteristics and social networks. [26] Although this study is ongoing, preliminary findings have been drawn from a secondary analysis of the American Terrorism Study data, which contain information on people federally indicted for terrorism-related crimes by the U.S. government between 1980 and 2002. [27] With these data, the researchers compared the demographic and homegrown violent extremist characteristics among military veterans and civilians. The demographic characteristics considered were age, race, sex, marital status, and education level. The homegrown violent extremist characteristics consisted of the length of group membership, type of terrorist group, role in the group, mode of recruitment into the group, primary target, and the state of indictment.

The research team observed significant differences between military veteran and civilian extremists across both demographic and homegrown violent extremist characteristics. First, they found that military veteran and civilian extremists differed with respect to age, sex, and marital status. Specifically, individuals with military service who engaged in homegrown violent extremism were more likely to be older, male, and in marital or cohabiting relationships than civilians who engaged in homegrown violent extremism. Second, analyses revealed that, compared to civilian extremists, military veteran extremists had greater affiliations with right-wing terrorist groups (versus left-wing, international, or other terrorist groups) and were more likely to hold leadership positions within these groups and either initiate a terrorist group or unite groups together. Finally, other than government/federal officials or buildings, which were the primary targets across all groups, the primary targets of veterans were diverse social groups, such as those belonging to racial, ethnic, and religious minority groups.

Implications of Transitioning Out of Military Service

The University of Southern California researchers intend to supplement these results by interviewing members from the social networks of military veterans and civilians who committed homegrown violent extremism between 2003 and 2019. The findings produced thus far are important, especially because the association between military experience and terrorism is understudied. Ultimately, these results suggest that people who transition from active duty to veteran status experience a nuanced, complex, and potentially lifelong process. Veterans who encounter difficulties during this transition and desire — but lack — a sense of community, purpose, and belonging after leaving the military may be attracted to the pull of domestic extremist groups. In these groups, veterans can lead and collaborate with others of similar ideologies to accomplish a shared mission akin to what they did in the military. For example, the military veterans in this study largely endorsed right-wing values; thus, perhaps something about the narratives of right-wing extremist groups compensates for the void felt when leaving military service. With such insights in mind, researchers recommend forming partnerships among civilians, the military, and veteran communities to identify and prevent violent extremism among U.S. veterans.

Longevity of Terrorist Plots in the United States

A major question for researchers and counterterrorism officials is how to prevent the next act of terrorism or violent extremism from occurring. As such, much attention has been paid to disrupted plots and successful interdiction tactics that ultimately led to arrest and indictment. Less attention has been given to what those responsible for acts of terrorism and violent extremism do to successfully evade detection and arrest. In other words, the focus has not been on what terrorists and violent extremists are doing “right.”

In 2013, NIJ funded researchers at the University of Arkansas’ Terrorism Research Center to study the sequencing of precursor behaviors for individuals who have been federally indicted in the United States for charges related to terrorism and domestic violent extremism. [28] Based on preliminary analyses, the researchers somewhat serendipitously observed lifespan differences between lone actors and those operating in small cells or more formalized groups. Consequently, it warranted a more comprehensive examination of the factors that increased the likelihood of terrorists and violent extremists evading arrest. NIJ funded the researchers to identify behaviors that improved the chances of plot longevity — or the ability for terrorists to commit acts of terrorism and evade capture by law enforcement — for individuals federally indicted on terrorism-related charges. [29]

Data on the longevity of terrorism and violent extremism plots come from the American Terrorism Study, the longest-running project on terrorism and violent extremism in the United States. With NIJ funding that began in 2003, [30] the American Terrorism Study maintains the most comprehensive dataset on temporally linked precursor behaviors and outcomes of terrorism and violent extremism plots. To examine plot longevity, the Arkansas researchers [31] limited their analyses to 346 federally indicted individuals who were linked to the planning or completion of a terrorist attack in the United States from 1980 to 2015. Longevity, or duration of their “terrorist lifespan,” is based on the date of a person’s involvement in their first preparatory activity and their “neutralizing” date (usually the date of arrest).

One of the key findings from this research is a correlation between significant declines in the lifespan of individual terrorists and major changes to the U.S. Attorney General guidelines established to combat terrorism and violent extremism in the United States. For example, those who began in the mid- to late 1970s, following Watergate, COINTELPRO, and the Privacy Act, had a median longevity of 2,230 days. In contrast, the median lifespan of terrorists who began operating in the mid-1980s decreased to 1,067 days. Later, in the early 2000s, it fell even further to 99 days, which reflects the FBI’s tighter focus on terrorism and violent extremism and guidelines granting law enforcement more discretion in the investigative techniques employed.

The researchers also found that the lifespans of terrorists and violent extremists vary significantly depending on key attributes, such as ideology, sex, and educational attainment. For example, environmental and extreme left-wing violent extremists tend to sustain themselves for relatively long periods of time (5.4 and 4.3 years, respectively), while the longevity of extreme right-wing and radical Islamist terrorists is, on average, two years or less.

Females federally indicted on charges related to terrorism and violent extremism also tend to have increased longevity compared to male terrorists and violent extremists, perhaps because of females’ disproportionate representation in longer-lasting extreme left-wing and environmental movements, as well as increased representation in left-wing group leadership roles. Females involved in terrorism and extremism are usually more educated, which is also associated with extended longevity. Further, females who play support roles in terrorism and extremist groups — as is more often the case for right-wing extremists and radical Islamist terrorists — also appear to have longer lifespans. In contrast, males have been more likely to engage in overtly criminal preparatory behavior and actual incident participation than females. Both types of behavior are significantly more likely to attract the attention of law enforcement and would be expected to shorten the longevity of both male and female terrorists and violent extremists.

Finally, longevity also depends on a plot’s sophistication and the extent of the planning required to carry it out. Less sophisticated plans or executed plots, or those using simpler and less advanced weapons, are generally associated with longer lifespans for terrorists and violent extremists. More sophisticated plots may provide greater potential for missteps by terrorists and violent extremists and leads for law enforcement. Additionally, more sophisticated plots are associated with more meetings with accomplices and necessitate extra preparation. Importantly, both the number of meetings and preparatory activities have been found to be negatively related to the successful completion of terrorist incidents, suggesting that early intervention or arrest are also linked to these two factors.

How Domestic Terrorists Use the Internet

Terrorists and terrorist groups use the internet to share propaganda and recruit new members. The internet provides a platform to strengthen their members’ commitment to the cause, encourage radicalized individuals to act, and coordinate legal and illegal activities. A recently published meta-analysis concluded, “Exposure to radical content online appears to have a larger relationship with radicalization than other media-related risk factors (for example, television usage, media exposure), and the impact of this relationship is most pronounced for the behavioral outcomes of radicalization.” [32]

In 2014, NIJ funded a study to develop a deeper understanding of what domestic terrorists discuss on the internet. [33] The study analyzed 18,120 posts from seven online web forums by and for individuals interested in the ideological far right. The research team read each post’s content and coded it for either quantitative or qualitative analyses depending on the project’s objective.

The project provided several important insights into terrorist use of the internet. First, the web forums included discussions about a variety of beliefs, such as gun rights, conspiracy theories, hate-based sentiments, and anti-government beliefs; however, the intensity of ideological expression was generally weak. The nature of the online environments that far-right groups use likely facilitates the diffusion of ideological agendas.

Second, the amount and type of involvement in these forums played a key role in radicalization. Posting behaviors changed over time. Users grew more ideological and radical as other users reinforced their ideas and connected their ideas to those from other forums. (It is important to note that the study focused on online expression and not conversion to offline violence.)

Third, far-right extremists were primarily interested in general technology issues. Discussions focused on encryption tools and methods (such as Tor), internet service providers and social media platforms, and law enforcement actions to surveil illicit activities online. These far-right extremists appeared more interested in defensive actions than sophisticated schemes for radicalization or offensive actions such as criminal cyberattacks.

The study used social network analyses to visualize user communications and network connections, focusing on individuals’ responses to posts made within threads to highlight interconnected associations between actors. The social network analyses indicated that far-right forums have a low network density, which suggests a degree of information recycling between key actors. The redundant connections between actors may slow the spread of new information. As a result, such forums may inefficiently distribute new knowledge due to their relatively insular nature. They may also be generally difficult to disrupt, as the participants’ language and behaviors reinforce others and create an echo chamber. These networks are similar to others observed in computer hacker communities and data theft forums, [34] which suggests that there may be consistencies in the nature of online dialogue regardless of the content.

The study also indicated that extreme external events usually did not affect posting behaviors. However, there were significant differences associated with conspiratorial, anti-Islamic, and anti-immigrant posts after the Boston Marathon bombing. It may be that violence or major disruptive events inspired by jihadist ideologies draw great responses from far-right groups relative to their own actions. The same appears to be true for the 2012 presidential election; the study observed increases both in the number of posts in the month after the election and in overt signs of individual ties or associations to far-right movements through self-claim posts, movement-related signatures, and usernames. These findings are consistent with other recent work comparing online mobilization after the 2012 and 2016 presidential elections. [35]

Entering and Exiting White Supremacy in the United States

An NIJ-funded research team led by RTI International examined the complex social-psychological processes involved with entering, mobilizing, and exiting white supremacy in the United States. [36] The researchers conducted in-depth life history interviews with 47 former members of white supremacist groups in 24 states and two provinces in Canada. [37]

For this project, white supremacy referred to groups that reject essential democratic ideals, equality, and tolerance. A key organizing principle is that inherent differences between races and ethnicities position white and European ancestry above all others. Those interviewed were authoritarian, anti-liberal, or militant nationalists who had a general intolerance toward people of color. They had used violence to achieve their goals and supported a race war to eradicate the world of nonwhite people. [38]

The study led to several key findings about entering and exiting white supremacy in the United States.

Hate as Outcome

The study found that most people do not join white supremacist groups because they are adherents of a particular ideology. Rather, a combination of background factors increases the likelihood that someone will be susceptible to recruitment messaging (for example, propaganda). [39] Previous research has highlighted that hate or adherence to racist violence was an outcome of participation in white supremacist groups. [40] The commitment to white supremacist groups lacked a preexisting sense of racial grievance or hatred that motivated an individual to join the racist movement. [41] One former member reported having “no inkling of what [Nazism] really was other than what you saw on TV.” [42] The NIJ-funded study found that people joined white supremacist groups because they were angry, lonely, and isolated, and they were looking for opportunities to express their rage. [43]

Vulnerabilities as Precondition

The former white supremacists had various personal, psychological, and social vulnerabilities that made them strive for what psychologists have framed as developing a new possible self. [44] High levels of negative life experiences — including, but not limited to, maladjustment, abuse, and family instability — potentially make a person imagine a new, different, and more fulfilled self. [45] They can imagine an empowered future self with friends and a purpose. Extremist recruiters prey on these desires. The former white supremacists indicated high levels of physical, sexual, and psychological abuse as children; strained personal relationships; and general difficulties throughout their lives. These struggles made white supremacy seem like an improvement to their sense of self, as the group came with a ready-made set of friends, social events, and camaraderie among individuals with similarly rough pasts. Besides these social benefits, white supremacist groups provided members with a deeper sense of belonging and explanation for their life troubles, rooted in a sense of racial pride and empowerment.

Gradual, Nonlinear Exit

Most white supremacists in this country do not remain members for life. Rather, group membership is often temporary (but not always short-lived), and many become disillusioned and burnt out over time. The study showed that the exit process is gradual, as the former white supremacists reported slowly becoming dissatisfied with the ideology, tactics, or politics of a group. [46] They described an identity that became filled with negative encounters with other members, even breeding distrust. White supremacy requires the development of a totalizing identity that results in isolating members from nonextremists. This marginalization fosters a sense of social stigma that makes white supremacy less attractive and further supports disengagement and deradicalization processes.

This research reported that emotional dynamics create trajectories of development and decline in white supremacy and the role of disillusionment among the reasons why members exit the organization. [47] These analyses offer an explanation for how white supremacist organizations maintain solidarity even though many individuals stay in groups after losing their ideological commitment. They also demonstrate that exit from a group is a nonlinear process. [48] Meanwhile, in other analyses, the study team reported that, even after an individual exits a group, their white supremacist identity lingers with a residual effect. [49] That research likened hate to an addiction that creates an uncontrollable emotional, social, and cognitive hold over adherents, which has the ability to pull former members back into hate almost against their will. [50] The former white supremacists shared experiences in which music, environments, and images created desire, longing, and curiosity about their old lifestyle within the organization.

Opportunities

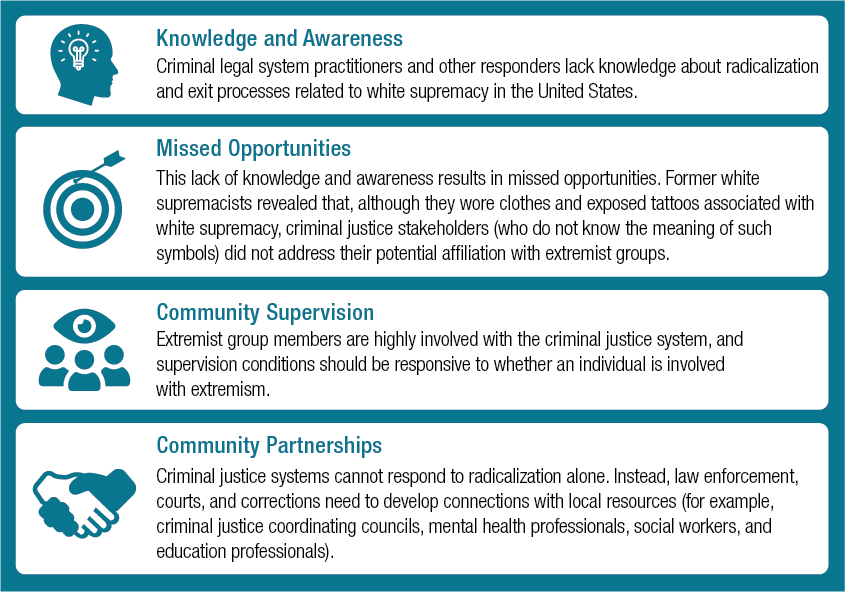

The NIJ-funded study found several blind spots in terms of identification and awareness among criminal legal system practitioners and other responders. This resulted in several missed opportunities for intervention and practical solutions. Exhibit 1 details four areas in which the study findings can contribute to criminal justice policy and practice. [51]

Exhibit 1. Missed Opportunities for Intervention and Practical Solutions

Policy Implications

The results of the NIJ-funded studies discussed in this article have several implications for policy and practice. First, they illustrate that extremism is complex and that successfully countering it will require a unified response that bridges law enforcement, community partners, health officials, and concerned citizens. To facilitate a shared understanding of the extremist threat, stakeholders engaged in counterextremism efforts routinely use findings from these studies to provide training to concerned family and friends about potential radicalization warning signs and how best to respond. They also use the findings to educate law enforcement, corrections and probation officers, and mental health professionals on the complexity of radicalization so they can accurately gauge and respond to extremism in their communities. These types of training initiatives will remain critical to counterextremism efforts as the threat continues to evolve.

Second, the studies highlight the importance of focusing criminal justice resources on domestic extremism. Although international terrorist organizations remain a threat, these studies show that domestic extremists continue to be responsible for most terrorist attacks in the United States. Historically, far fewer resources have been dedicated to the study of domestic extremism, leaving gaps in our understanding about terrorist trends, recruitment and retention processes, and online behaviors. Due in large part to NIJ’s commitment to funding research on domestic radicalization, considerable progress has recently been made in addressing these topics. But this work will need to continue if we hope to keep pace with the rapidly evolving threat landscape.

Finally, the studies highlight the need for communitywide partnerships that link government and nongovernment organizations in support of community-level prevention and intervention programs. Law enforcement and criminal justice resources for countering extremism are finite and scarce, making it imperative that we focus our research and support efforts on understanding what occurs before a crime takes place. As the studies reviewed in this article show, there is often an opportunity to intervene to help individuals exit extremism before they engage in criminal activity. Similarly, prevention efforts are needed in digital spaces where extremist narratives often flourish. Achieving these goals will require community members, policymakers, and practitioners to commit to supporting counterextremism efforts.

About This Article

This article was published as part of NIJ Journal issue number 285 . This article discusses the following awards:

- “Exploring the Social Networks of Homegrown Violent Extremist Military Veterans,” award number 2019-ZA-CX-0002

- “Sequencing Terrorists’ Precursor Behaviors: A Crime Specific Analysis,” award number 2013-ZA-BX-0001

- “Radicalization and the Longevity of American Terrorists: Factors Affecting Sustainability,” award number 2015-ZA-BX-0001

- “Pre-Incident Indicators of Terrorist Incidents,” award number 2003-DT-CX-0003

- “Empirical Assessment of Domestic Radicalization (EADR),” award number 2012-ZA-BX-0005

- “A Pathway Approach to the Study of Bias Crime Offenders,” award number 2017-VF-GX-0003

- “Research and Evaluation on Domestic Radicalization to Violent Extremism: Research To Support Exit USA,” award number 2014-ZA-BX-0005

- “Assessment of Extremist Groups Use of Web Forums, Social Media, and Technology To Enculturate and Radicalize Individuals to Violence,” award number 2014-ZA-BX-0004

Opinions or points of view expressed in this document represent a consensus of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position, policies, terminology, or posture of the U.S. Department of Justice on domestic violent extremism. The content is not intended to create, does not create, and may not be relied upon to create any rights, substantive or procedural, enforceable at law by any party in any matter civil or criminal.

[note 1] Celinet Duran, “ Far-Left Versus Far-Right Fatal Violence: An Empirical Assessment of the Prevalence of Ideologically Motivated Homicides in the United States ,” Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society 22 no. 2 (2021): 33-49; Joshua D. Freilich et al., “ Introducing the United States Extremist Crime Database (ECDB) ,” Terrorism and Political Violence 26 no. 2 (2014): 372-384; and William Parkin, Joshua D. Freilich, and Steven Chermak, “ Did Far-Right Extremist Violence Really Spike in 2017? ” The Conversation, January 4, 2018.

[note 2] Duran, “ Far-Left Versus Far-Right Fatal Violence ”; Freilich et al., “ Introducing the United States Extremist Crime Database (ECDB) ”; and Parkin, Freilich, and Chermak, “ Did Far-Right Extremist Violence Really Spike in 2017? ”

[note 3] U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Homeland Threat Assessment: October 2020 , Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2020, 4.

[note 4] Allison G. Smith, How Radicalization to Terrorism Occurs in the United States: What Research Sponsored by the National Institute of Justice Tells Us , Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, June 2018, NCJ 250171; and Michael Wolfowicz, Badi Hasisi, and David Weisburd, “ What Are the Effects of Different Elements of Media on Radicalization Outcomes? A Systematic Review ,” Campbell Systematic Reviews 18 no. 2 (2022).

[note 5] Aisha Javed Qureshi, “ Understanding Domestic Radicalization and Terrorism: A National Issue Within a Global Context ,” NIJ Journal 282, August 2020.

[note 6] National Institute of Justice funding award description, “ Empirical Assessment of Domestic Radicalization (EADR) ,” at the University of Maryland, award number 2012-ZA-BX-0005.

[note 7] National Institute of Justice funding award description, “ A Pathway Approach to the Study of Bias Crime Offenders ,” at the University of Maryland, College Park, award number 2017-VF-GX-0003.

[note 8] The PIRUS and BIAS datasets are based on the same data collection methodologies and share similar goals. Both contain random samples of individuals who committed crimes in the United States that were motivated by their extremist ideologies or hate beliefs. The PIRUS dataset includes 2,225 individuals from 1948 to 2018, and BIAS is based on 966 cases from 1990 to 2018. Both datasets are collected entirely from public sources, including court records, online and print news, and public social media accounts. Both seek to capture individuals who promoted a range of extremist ideologies and hate beliefs. PIRUS, for instance, includes those whose crimes were associated with anti-government, white supremacist, environmental, anarchist, jihadist, and conspiracy theory movements. Similarly, BIAS includes individuals who selected victims based on their race, ethnicity, and nationality; sexual orientation and gender identity; religious affiliation; age; or disability.

[note 9] Michael Jensen and Gary LaFree, “ Final Report: Empirical Assessment of Domestic Radicalization (EADR) ,” Final report to the National Institute of Justice, award number 2012-ZA-BX-0005, December 2016, NCJ 250481; and Michael A. Jensen, Elizabeth A. Yates, and Sheehan E. Kane, “ A Pathway Approach to the Study of Bias Crime Offenders ,” Final report to the National Institute of Justice, award number 2017-VF-GX-0003, February 2021, NCJ 300114.

[note 10] Michael Jensen, Elizabeth Yates, and Sheehan Kane, “ Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States (PIRUS) ,” Research Brief, College Park, MD: National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism [START], May 2020.

[note 11] Jensen, Yates, and Kane, “ Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States (PIRUS) .”

[note 12] Jensen, Yates, and Kane, “ A Pathway Approach to the Study of Bias Crime Offenders .”

[note 13] Jensen and LaFree, “ Final Report: Empirical Assessment of Domestic Radicalization (EADR) ”; and Jensen, Yates, and Kane, “ A Pathway Approach to the Study of Bias Crime Offenders .”

[note 14] Michael Jensen, Elizabeth Yates, and Sheehan Kane, “ Characteristics and Targets of Mass Casualty Hate Crime Offenders ,” College Park, MD: START, 2020.

[note 15] Jensen, Yates, and Kane, “ A Pathway Approach to the Study of Bias Crime Offenders .”

[note 16] John Horgan, “ From Profiles to Pathways and Roots to Routes: Perspectives From Psychology on Radicalization Into Terrorism ,” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 618 no. 1 (2008): 80-94.

[note 17] Jensen, Yates, and Kane, “ Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States (PIRUS) .”

[note 18] Gary LaFree, “ Correlates of Violent Political Extremism in the United States ,” Criminology 56 no. 2 (2018): 233-268; Michael A. Jensen, Anita Atwell Seate, and Patrick A. James, “ Radicalization to Violence: A Pathway Approach To Studying Extremism ,” Terrorism and Political Violence 32 no. 5 (2020): 1067-1090; and Michael A. Jensen et al., “ The Link Between Prior Criminal Record and Violent Political Extremism in the United States ,” in Understanding Recruitment to Organized Crime and Terrorism, ed. David Weisburd et al. (New York: Springer, 2020), 121-146.

[note 19] Jensen, Yates, and Kane, “ Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States (PIRUS) .”

[note 20] Michael Jensen, Elizabeth Yates, and Sheehan Kane, “ Violent Hate Crime Offenders ,” College Park, MD: START, 2020.

[note 21] Unless otherwise noted, all data reported in this section originate from Michael Jensen, Elizabeth Yates, and Sheehan Kane, Radicalization in the Ranks: An Assessment of the Scope and Nature of Criminal Extremism in the United States Military , College Park, MD: START, January 2022. In this project, extremists with military backgrounds consisted of active and nonactive personnel from all military branches and reserves, aside from the Space Force and Coast Guard Reserves. Individuals who were honorably discharged, dishonorably discharged, or otherwise violated the Uniform Code of Military Justice were excluded from the study. Also excluded were those discharged through court martial unless information about their criminal proceedings was publicly available.

[note 22] Allison G. Smith, Risk Factors and Indicators Associated With Radicalization to Terrorism in the United States: What Research Sponsored by the National Institute of Justice Tells Us , Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, June 2018, NCJ 251789.

[note 23] Jensen and LaFree, “ Final Report: Empirical Assessment of Domestic Radicalization (EADR) .”

[note 24] Smith, Risk Factors and Indicators Associated With Radicalization to Terrorism in the United States .

[note 25] Smith, Risk Factors and Indicators Associated With Radicalization to Terrorism in the United States .

[note 26] National Institute of Justice funding award description, “ Exploring the Social Networks of Homegrown Violent Extremist (HVE) Military Veterans ,” at the University of Southern California, award number 2019-ZA-CX-0002.

[note 27] Unless otherwise noted, all data in this section come from Hazel R. Atuel and Carl A. Castro, “ Exploring Homegrown Violent Extremism Among Military Veterans and Civilians ,” The Military Psychologist 36 no. 3 (2021): 10-14.

[note 28] National Institute of Justice funding award description, “ Sequencing Terrorists? Precursor Behaviors: A Crime Specific Analysis ,” at the University of Arkansas, award number 2013-ZA-BX-0001.

[note 29] National Institute of Justice funding award description, “ Radicalization and the Longevity of American Terrorists: Factors Affecting Sustainability ,” at the University of Arkansas, award number 2015-ZA-BX-0001.

[note 30] National Institute of Justice funding award description, “ Pre-Incident Indicators of Terrorist Incidents ,” at the Board of Trustees, University of Arkansas, award number 2003-DT-CX-0003.

[note 31] Unless otherwise noted, all data in this section come from Brent L. Smith et al., “ The Longevity of American Terrorists: Factors Affecting Sustainability ,” Final Summary Overview, award number 2015-ZA-BX-0001, January 2021, NCJ 256035.

[note 32] Wolfowicz, Hasisi, and Weisburd, “ What Are the Effects of Different Elements of Media on Radicalization Outcomes ?”

[note 33] Unless otherwise noted, all data in this section come from Thomas J. Holt, Steve Chermak, and Joshua D. Freilich, “ An Assessment of Extremist Groups Use of Web Forums, Social Media, and Technology To Enculturate and Radicalize Individuals to Violence ,” Final Summary Overview, award number 2014-ZA-BX-0004, January 2021, NCJ 256038.

[note 34] Thomas J. Holt and Adam M. Bossler, “Issues in the Prevention of Cybercrime,” in Cybercrime in Progress: Theory and Prevention of Technology-Enabled Offenses (New York: Routledge, 2016), 136-168.

[note 35] Ryan Scrivens et al., “ Triggered by Defeat or Victory? Assessing the Impact of Presidential Election Results on Extreme Right-Wing Mobilization Online ,” Deviant Behavior 42 no. 5 (2021): 630-645.

[note 36] Matthew DeMichele, Peter Simi, and Kathleen Blee, “ Research and Evaluation on Domestic Radicalization to Violent Extremism: Research To Support Exit USA ,” Final report to the National Institute of Justice, award number 2014-ZA-BX-0005, January 2021, NCJ 256037.

[note 37] The project included three human rights groups (Anti-Defamation League, Simon Wiesenthal Center, and Southern Poverty Law Center) and Life After Hate, an organization that assists white supremacists in exiting the movement. The project partners helped develop a semi-structured interview protocol and provided contact information for initial interviewees. The study used a snowballing technique from these initial interviewees to identify former white supremacists who were in the public sphere to determine if they were interested in being interviewed. The interviews were conducted in places where the individuals would be comfortable, including hotel rooms, homes, places of work, coffee shops, restaurants, and parks. The interviews were in-depth accounts (lasting 6-8 hours each) of individuals’ backgrounds (for example, how they grew up), entry into white supremacy (for example, how they learned about the movement), mobilization (for example, rank and use of violence), and exit process (for example, initial doubts and barriers to exit). The completion of the project was a collaboration with equal contributions from Kathleen Blee, Matthew DeMichele, and Pete Simi and support from Mehr Latif and Steven Windisch.

[note 38] Steven Windisch et al., “ Understanding the Micro-Situational Dynamics of White Supremacist Violence in the United States ,” Perspectives on Terrorism 12 no. 6 (2018): 23-37.

[note 39] DeMichele, Simi, and Blee, “ Research and Evaluation on Domestic Radicalization to Violent Extremism: Research To Support Exit USA .”

[note 40] Kathleen M. Blee et al., “ How Racial Violence Is Provoked and Channeled ,” Socio 9 (2017): 257-276.

[note 41] Blee et al., “ How Racial Violence Is Provoked and Channeled .”

[note 42] Blee et al., “ How Racial Violence Is Provoked and Channeled ,” 265.

[note 43] DeMichele, Simi, and Blee, “ Research and Evaluation on Domestic Radicalization to Violent Extremism: Research To Support Exit USA .”

[note 44] Hazel Markus and Paula Nurius, “ Possible Selves ,” American Psychologist 41 no. 9 (1986): 954-969.

[note 45] Unless otherwise noted, all data in the remainder of this paragraph come from DeMichele, Simi, and Blee, “ Research and Evaluation on Domestic Radicalization to Violent Extremism: Research To Support Exit USA .”

[note 46] All data in this paragraph come from DeMichele, Simi, and Blee, “ Research and Evaluation on Domestic Radicalization to Violent Extremism: Research To Support Exit USA .”

[note 47] Mehr Latif et al., “ How Emotional Dynamics Maintain and Destroy White Supremacist Groups ,” Humanity & Society 42 no. 4 (2018): 480-501.

[note 48] Latif et al., “ How Emotional Dynamics Maintain and Destroy White Supremacist Groups .”

[note 49] Pete Simi et al., “ Addicted to Hate: Identity Residual Among Former White Supremacists ,” American Sociological Review 82 no. 6 (2017): 1167-1187.

[note 50] Simi et al., “ Addicted to Hate .”

[note 51] DeMichele, Simi, and Blee, “ Research and Evaluation on Domestic Radicalization to Violent Extremism: Research To Support Exit USA .”

About the author

Steven Chermak, Ph.D., is a professor in the School of Criminal Justice at Michigan State University and studies domestic terrorism and cyber offending. Matthew DeMichele, Ph.D., is a senior research sociologist at RTI and has conducted research on correctional population trends, risk prediction, terrorism/extremism prevention, and program evaluation. Jeff Gruenewald, Ph.D., is a professor and director of the Terrorism Research Center at the University of Arkansas and studies domestic violent extremism and hate crime. Michael Jensen, Ph.D., is a senior researcher at the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism at the University of Maryland, where he leads the team on extremism in the United States. Raven Lewis, MA, is a Ph.D. candidate at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey, and a former research assistant at the National Institute of Justice, where she supported research efforts focused on domestic radicalization and violent extremism. Basia E. Lopez, MPA, is a social science analyst at the National Institute of Justice, where she leads the firearm violence and mass shootings research portfolio and co-leads the violent extremism and domestic radicalization research portfolio.

Cite this Article

Read more about:, related awards.

- Exploring the Social Networks of Homegrown Violent Extremist (HVE) Military Veterans

- SEQUENCING TERRORISTS? PRECURSOR BEHAVIORS:A CRIME SPECIFIC ANALYSIS

- Radicalization and the Longevity of American Terrorists: Factors Affecting Sustainability

- Pre-incident Indicators of Terrorist Incidents

- Empirical Assessment of Domestic Radicalization

- A Pathway Approach to the Study of Bias Crime Offenders

- Research and Evaluation on Domestic Radicalization to Violent Extremism: Research to Support Exit USA

Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident Due to planned maintenance there will be periods of time where the website may be unavailable. We apologise for any inconvenience.

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > British Journal of Political Science

- > Volume 52 Issue 2

- > Terrorism and Migration: An Overview

Article contents

Terrorism preliminaries, migration as a cause of transnational terrorism, the effects of terrorism on attitudes towards immigrants, electoral behavior and immigration policies, terrorism and migration: an overview.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 17 December 2020

This article provides an overview of the literature on the relationship between terrorism and migration. It discusses whether and how (1) migration may be a cause of terrorism, (2) terrorism may influence natives' attitudes towards immigration and their electoral preferences and (3) terrorism may lead to more restrictive migration policies and how these in turn may serve as effective counter-terrorism tools. A review of the empirical literature on the migration–terrorism nexus indicates that (1) there is little evidence that more migration unconditionally leads to more terrorist activity, especially in Western countries, (2) terrorism has electoral and political (but sometimes short-lived) ramifications, for example, as terrorism promotes anti-immigrant resentment and (3) the effectiveness of stricter migration policies in deterring terrorism is rather limited, while terrorist attacks lead to more restrictive migration policies.

Shortly after taking office in January 2017, US President Donald Trump issued Executive Order 13769, called ‘Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States’ (Trump Reference Trump 2017 ). This order instituted a number of immigration restrictions, especially concerning immigration and travel from Muslim-majority countries to the United States. Explicitly referring to the 9/11 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, DC, Trump ( Reference Trump 2017 , 8977) argued that these restrictions were necessary because

[n]umerous foreign-born individuals have been convicted or implicated in terrorism-related crimes since 11 September 2001, including foreign nationals who entered the United States after receiving visitor, student, or employment visas, or who entered through the United States refugee resettlement program.

Thus the purpose of these immigration restrictions (which included suspending the issuance of visas and denying immigrants from certain countries entry into the United States) was ‘to protect the American people from terrorist attacks by foreign nationals admitted to the United States’ (Trump Reference Trump 2017 , 8977). Footnote 1

Trump's executive order is emblematic of how some politicians relate terrorism to immigration: migrants Footnote 2 are regarded as a potential threat to domestic security given the chance they will engage in terrorist activity. In recent years, Muslim immigration in particular has been considered a security threat to Western societies (for example, Givens et al. Reference Givens, Freeman and Leal 2009 ; Sides and Gross Reference Sides and Gross 2013 ). Furthermore, as exemplified by Trump's travel ban, the ostensible relationship between terrorism and migration has public policy consequences . More generally, since the 9/11 attacks in the United States, many policy measures in fields such as surveillance, immigration and foreign policy have been justified with the security threat that immigrants ostensibly pose (for example, Chebel d'Appollonia Reference Chebel d'Appollonia 2012 ; Davis and Silver Reference Davis and Silver 2004 ; Givens et al., Reference Givens, Freeman and Leal 2009 ; Huddy et al. Reference Huddy, Norris, Kern and Just 2002 ). Consequently, the alleged effect of migration on terrorism will also matter to electoral politics . For instance, Wright and Esses ( Reference Wright and Esses 2019 ) show that individuals who perceived immigrants as a security concern were more likely to vote for Donald Trump, who explicitly campaigned on an anti-immigration and tough-on-terror platform, in the 2016 US elections.

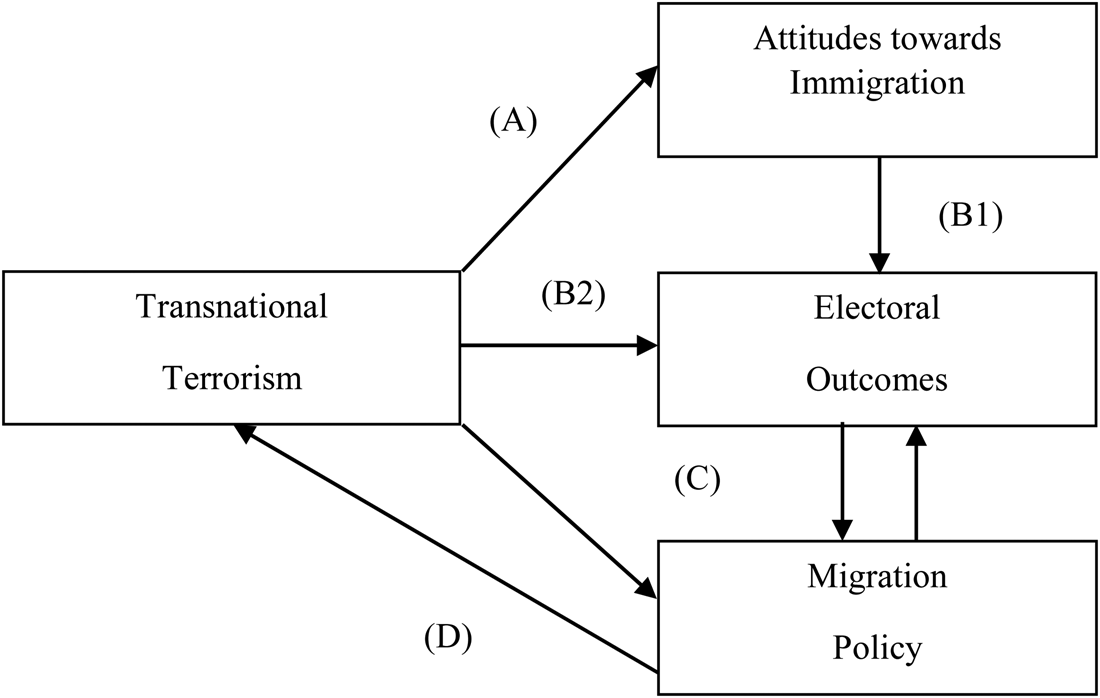

Motivated by recent political, electoral and security events such as the election and politics of Donald Trump, the rise of right-wing anti-immigrant parties in Europe and a number of high-profile terrorist attacks committed by migrants in the West (for example, the Paris attacks of November 2015 and the Berlin attack of December 2016), we provide a state-of-the-art overview of the literature on the migration–terrorism nexus . Footnote 3 Virtually all studies that address the relationship between migration and terrorism have been published over the last twenty years; many of them are only a few years old. The topic has attracted research interest in various fields such as economics, political science, sociology and social psychology. This allows us to consider the migration – terrorism nexus from various and complementary viewpoints. When reviewing the literature, we are interested in answering three (related) research questions:

(1) Does immigration lead to terrorism? In other words, is there empirical evidence to support the argument often raised in political and public debates that migration carries a risk to national security in the form of terrorism?

(2) What are the electoral consequences of terrorism? In particular, to what extent do terrorist attacks shape individual citizens' views about immigration and their electoral preferences?

(3) What is the relationship between terrorism and migration policy? Does terrorism lead to stricter migration policies, and do these measures, in turn, decrease the number of terrorist attacks a country experiences?

To answer these questions, we proceed as follows. After defining the term ‘terrorism’ and discussing its development across time and space, we review the literature that examines the role of migration as a potential cause of terrorism. Here, we also study how terrorism may be related to migration in origin countries. The next section focuses on the effects of terrorism in the destination countries. More specifically, we look at how terrorist attacks contribute to the politicization and framing of migration as a security issue by affecting attitudes towards immigrants, electoral behavior and migration policy making. The final section concludes.

Definition of Terrorism

According to Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler ( Reference Enders and Sandler 2011 , 321), terrorism can be defined as ‘[…] the premeditated use or threat to use violence by individuals or subnational groups against noncombatants in order to obtain a political or social objective through the intimidation of a large audience beyond that of the immediate victims’.

According to this definition, terrorism is distinct from (1) unorganized forms of violent political protest (including riots, mob violence), (2) non-political acts of violence (such as violent crime, school shootings) and (3) violent repression by the government, that is, state terrorism (for example, in the form of torture). Terrorism may, however, overlap with large-scale civil wars, meaning that non-state actors may resort to both terrorism and more conventional guerilla warfare in certain conflicts at the same time (for example, Gaibulloev and Sandler Reference Gaibulloev and Sandler 2019 : 291–292; Krieger and Meierrieks Reference Krieger and Meierrieks 2011 ; for a general introduction to terrorism studies, see Enders and Sandler Reference Enders and Sandler 2011 ).

Domestic terrorism is ‘homegrown [so that] the venue, target, and perpetrators are all from the same country’ (Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler Reference Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler 2011 , 321), while transnational terrorism concerns more than one country. Prominent examples of transnational terrorism are the 9/11 attacks: the perpetrators hailed from several Middle Eastern countries, while the attacks occurred in the United States and victimized thousands of US and non-US citizens.

Since migrants are, by definition, foreign nationals, transnational terrorism is particularly relevant for the study of the nexus between terrorism and migration. Transnational terrorism can be divided into two categories: (1) terrorism carried out by immigrants (foreign nationals) in their destination country, directed either against the inhabitants and institutions of the destination country or against other foreign nationals and (2) terrorism committed by natives (inhabitants of the destination country) against immigrants.

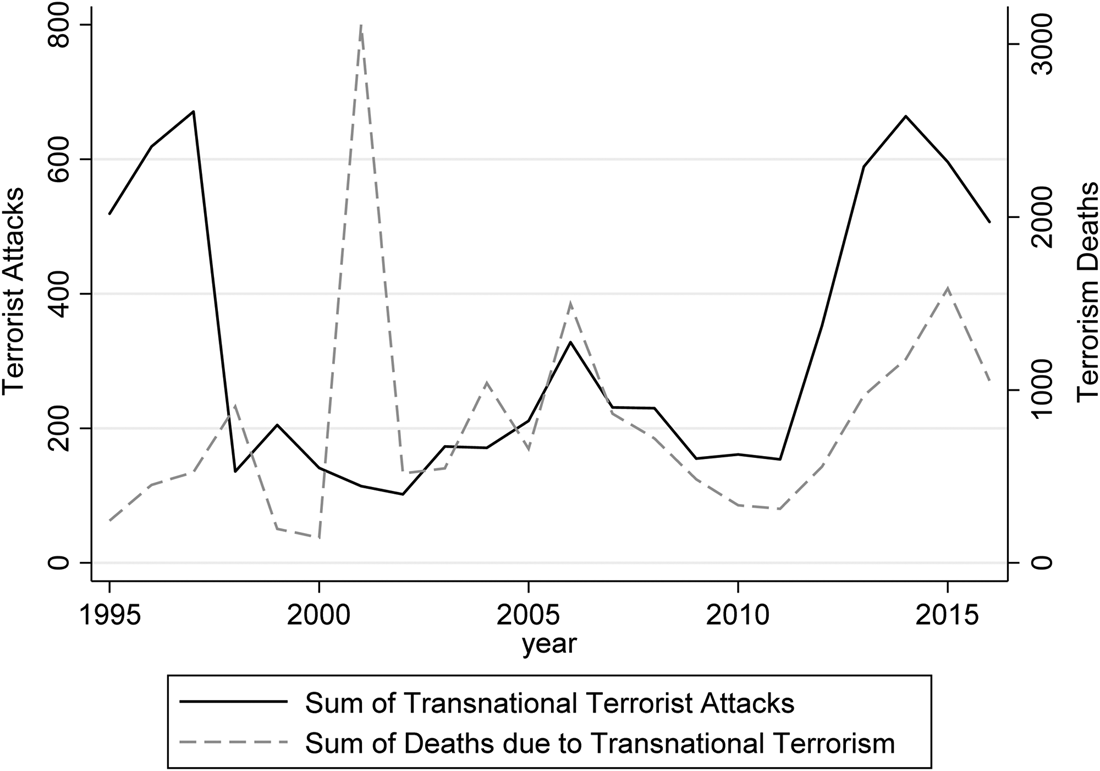

Trends in Transnational Terrorism since 1995

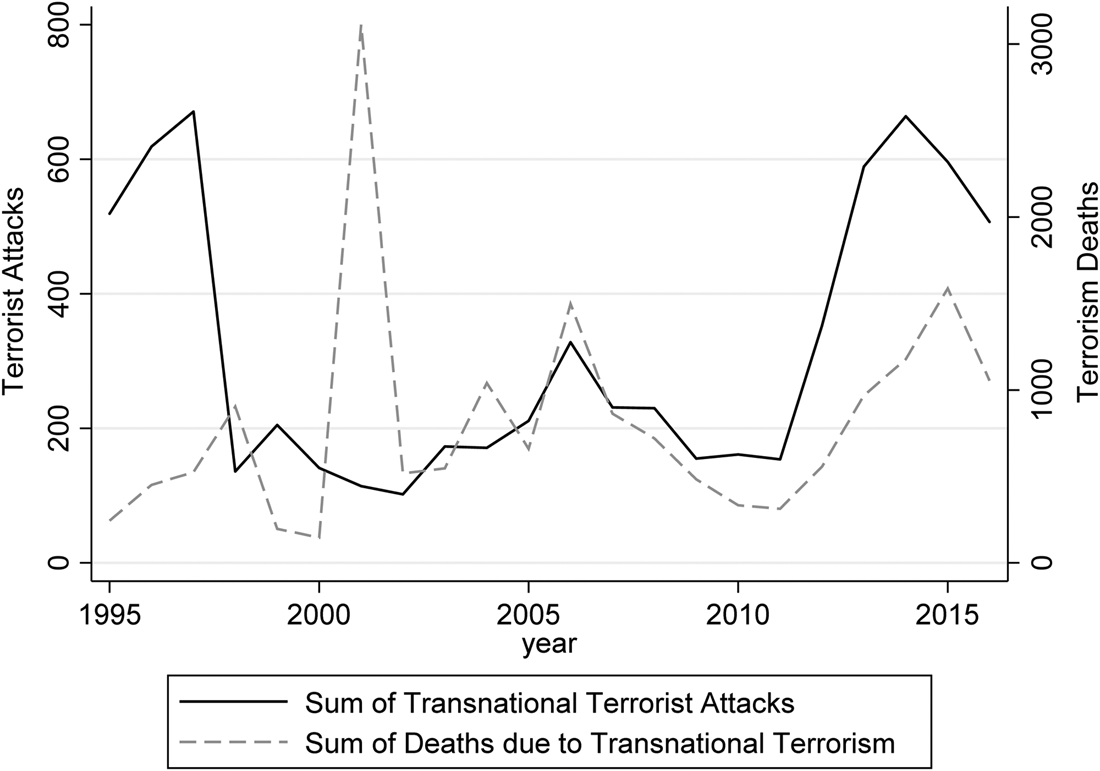

Figure 1 depicts global trends in transnational terrorism frequency and ferocity. The data used to construct this figure are drawn from Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler ( Reference Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler 2011 ) and Gaibulloev and Sandler ( Reference Gaibulloev and Sandler 2019 ). These authors use raw data from the Global Terrorism Database, first described in LaFree and Dugan ( Reference LaFree and Dugan 2007 ), applying various calibration and recoding methods to differentiate between domestic and transnational terrorism. Footnote 4 On average, between 1995 and 2016 there were approximately 320 transnational terrorist attacks with approximately 810 deaths per year. Transnational terrorism was fairly persistent with respect to its frequency and ferocity between the mid-1990s and 2010, with the noticeable exception of the spike in terrorism lethality in 2001 due to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. It became more common and deadly after 2010.

Figure 1. Global trends in transnational terrorism, 1995–2016

Sources : Global Terrorism Database; Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler ( Reference Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler 2011 ), Gaibulloev and Sandler ( Reference Gaibulloev and Sandler 2019 ).

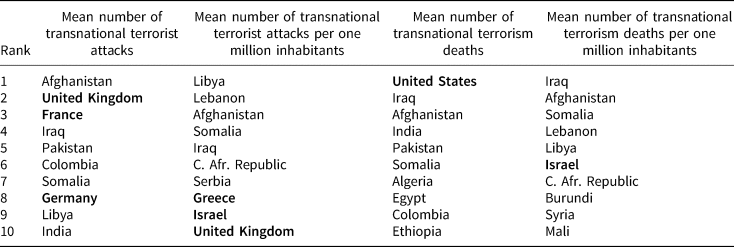

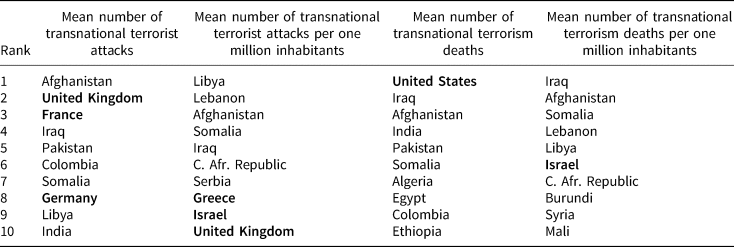

Table 1 shows that since the end of the Cold War, transnational terrorism has primarily affected countries in Africa, Asia and the Middle East. However, rich and industrialized (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD) countries have also been affected. Left-wing transnational terrorism has become less common after the end of the Cold War due to the loss of popular support for (and state sponsorship of) left-wing terrorist groups; however, pockets of this type of terrorism still exist, such as in Colombia (the ELN) and India (the Naxalites). Yet, post-1995 transnational terrorism has been much more strongly dominated by nationalist-separatist (for example, the Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosovës in Serbia/Kosovo) and especially religious-Islamist terrorist groups, for example, in Afghanistan (the Taliban), Iraq and Syria (Islamic State), Somalia (al-Shabaab) and Algeria (al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb). These trends in transnational terrorism are also described in more detail in Gaibulloev and Sandler ( Reference Gaibulloev and Sandler 2019 , 278–291).

Table 1. Geographical distribution of transnational terrorism, 1995–2016

Note : this list only considers countries that were always independent between 1995 and 2016 and that have more than one million inhabitants. Countries in bold were OECD members as of 2016.

In sum, the stylized facts about transnational terrorism since 1995 tell us that (1) it concerns many parts of the world, particularly (2) many countries in Asia, Africa and the Middle East from which migration to Western countries originates, while (3) the overall risk of transnational terrorism (as expressed by its frequency and lethality) tends to be rather marginal, notwithstanding the ‘outlier’ of the 9/11 attacks.

Theoretical Considerations

In this section, we discuss the empirical evidence on the potential effect of migration on terrorism. To theoretically understand how migration may affect terrorism, we employ a rational-choice model of terrorism . This model is the theoretical basis for many social science investigations of terrorism. Footnote 5 In short, it assumes that terrorists are rational actors who weigh the benefits of terrorism (such as achieving certain political goals) against its costs (for example, capture) and opportunity costs (for example, foregone earnings from non-violence when engaging in terrorism). Potential terrorists opt for violence (non-violence) when the benefits of terrorism outweigh its costs (benefits).

Migration may affect this terrorist calculus in two ways. First, it may make terrorism less costly. For instance, foreign terrorist organizations can use existing migration networks and routes to get terrorist operatives (for example, in the form of ‘sleeper cells’) into foreign countries at low costs, making subsequent terrorist activity by these operatives more probable. Similarly, foreign terrorist organizations can potentially rely on existing migrant communities in destination countries, so-called diasporas. Diasporas can be considered networks that provide their members with social bonds that produce mutual emotional and social support and reinforce common identities (for example, Sageman Reference Sageman 2004 ). Terrorist organizations linked to these diasporas (for example, due to a shared religious or ethnic background) can exploit these pre-existing networks for the purpose of radicalization, recruitment, financing, intelligence gathering and as safe havens (for example, Sageman Reference Sageman 2004 , Reference Sageman 2011 ; Sheffer Reference Sheffer and Richardson 2006 ). This ought to lower the operating costs of terrorist organizations and thus make terrorism – ceteris paribus – more likely.

Secondly, these very diasporas and migrant communities may also be subject to discrimination in destination countries such as in the form of religious intolerance or exclusion from the labor market or political representation (for example, Sheffer Reference Sheffer and Richardson 2006 ). Discrimination is a powerful predictor of terrorism (for example, Piazza Reference Piazza 2012 ; Saiya Reference Saiya 2019 ). It makes terrorism a more attractive option by lowering its opportunity costs, for example as opportunities for non-violent economic or political participation are constrained. Consequently, as migration leads to the growth of diasporas, it may also lead to the growth of grievances (due to discrimination) that could fuel terrorist violence by migrants.

The Effect of Migration on Terrorism in Destination Countries

Three large-N studies investigate the effect of migration on terrorism in the destination country of migration. First, Bove and Böhmelt ( Reference Bove and Böhmelt 2016 ) study this relationship for a sample of 145 countries between 1970 and 2000. They find that increases in migrant inflows lead to fewer terrorist attacks. Secondly, Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt ( Reference Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt 2020 ) examine migration from 183 origin to 20 OECD countries in a dyadic setting and come to the opposite conclusion: a larger number of foreigners leads to more terrorist activity in the host country. Thirdly, Forrester et al. ( Reference Forrester 2019 ) use bilateral migration data for 170 countries (thereby also including South–South migration) between 1995 and 2015, and find no evidence that immigration leads to more terrorism in destination countries.