Ten Masterpieces of Experimental Cinema

The following list by Justin Remes, author of Motion(less) Pictures: The Cinema of Stasis and the forthcoming Absence in Cinema: The Art of Showing Nothing , considers ten canonical experimental films. You can also watch the films below.

• • • • • •

“I don’t like experimental films.”

“What experimental films have you seen?”

“Well, I’m not sure I’ve ever really seen one, but…”

I’ve had this conversation more times than I can count.

While almost everyone has seen avant-garde paintings by Picasso and Pollock, few have ever had the opportunity to see an avant-garde film by Buñuel or Brakhage. Those who are interested in exploring this cinematic terrain might want to check out one or more of the following films, listed in chronological order. Since experimental films are often difficult to find, I have only included works that can currently be seen in high-quality versions online.

Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, Un Chien Andalou ( An Andalusian Dog ) (1929) (16 minutes) (NSFW)

In his autobiography, My Last Sigh , the great Surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel wrote, “I’ve tried my whole life to simply accept the images that present themselves to me without trying to analyze them.” This is precisely how one should approach the bizarre and irrational images of Un Chien Andalou : an eyeball being sliced open by a razor, ants swarming out of a hole in a man’s hand, two corpses buried in sand on a beach. Buñuel and Dalí pair these bewildering images with a soundtrack that includes a couple of sensual tangos, as well as the magisterial “Liebestod” (or “love death”) from Wagner’s opera Tristan and Isolde . Un Chien Andalou is disturbing, disorienting, and startlingly original. Those who see it never forget it.

Walter Ruttmann, Wochenende ( Weekend ) (1930) (11 minutes)

To create this odd intermedia experiment, the German filmmaker Walter Ruttmann wandered through the streets of Berlin and recorded his surroundings with a camera without ever removing the lens cap. In other words, Wochenende features a complex sound collage of voices, marching bands, and sirens, but it is completely devoid of images. Instead, spectators are free to imagine whatever content they like on the blank cinema screen before them. In the words of the Dada artist Hans Richter, Wochenende is “a symphony of sound, speech-fragments, and silence woven into a poem.”

Joseph Cornell, Jack’s Dream (c. 1938) (4 minutes)

American artist Joseph Cornell was a pioneer of found footage filmmaking (that is, creating films by reworking content from preexisting films), and Jack’s Dream is one of his most compelling cinematic remixes. As one listens to the gorgeous strains of Debussy’s Clair de Lune , one sees a number of apparently disconnected images: a puppet show, seahorses, a sinking ship. Like many actual dreams, Jack’s Dream is ephemeral and enigmatic.

Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) (13 minutes)

Albert Einstein once wrote, “The fairest thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true art and true science.” It is hard to think of a more mysterious film than Meshes of the Afternoon , a dreamscape that is replete with haunting and cryptic images: a flower that transforms into a knife, a woman who pulls a key out of her mouth, a hooded figure with a mirror for a face. Deren influenced just about every American experimental filmmaker who came after her, prompting Stan Brakhage to call her “the mother of us all.”

Note: When Meshes of the Afternoon was originally released, it was completely silent, but in 1959 a musical score by Deren’s third husband, Teiji Ito, was added. The silent version of the film is more compelling than the sound version, however, so if the version you are watching has sound, I would encourage you to mute it.

Stan Brakhage, Window Water Baby Moving (1959) (12 minutes) (NSFW)

The filmmaker Marjorie Keller once mused, “I don’t know that there could be an avant-garde filmmaker in America that is not in some way indebted to Stan Brakhage, has not studied his films, has not thought about them and taken them seriously.” While Brakhage made over 350 films, one of his most memorable and influential is Window Water Baby Moving , a work that documents the birth of Stan and Jane Brakhage’s first child, Myrrena. Brakhage uses rapid nonlinear editing, out-of-focus shots, reverse motion, and jump cuts to capture just how frenetic and disorienting childbirth can be.

Kenneth Anger, Scorpio Rising (1963) (28 minutes) (NSFW)

In the early 1960s, pop artists like Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol were revolutionizing the art world by appropriating images from popular culture: comic book characters, Hollywood celebrities, cans of Campbell’s soup. Kenneth Anger brought a similar sensibility to his film Scorpio Rising , a heady brew of religion, drugs, motorcycles, Nazis, and homoerotic sadomasochism. At a time when most filmmakers used classical music for their soundtracks, Anger used only contemporary pop songs, like Elvis Presley’s “You’re the Devil in Disguise” and Bobby Vinton’s “Blue Velvet.” Scorpio Rising is also populated with images drawn for popular culture: comic strip panels, gay pornography, and appropriated images of James Dean, Marlon Brando, Jesus, Dracula, and Hitler. One of Anger’s many acolytes, Martin Scorsese, confessed that when he first saw Scorpio Rising , he was “astonished”: “Every cut, every camera movement, every color, and every texture seemed, somehow, inevitable.”

Joyce Wieland, Cat Food (1967) (14 minutes)

Spectators of Cat Food hear crashing waves while watching Wieland’s insatiable cat, Dwight, voraciously eat fish. Whenever one fish starts to be consumed, another seems to miraculously appear. The film has a mythic quality, bringing to mind the New Testament story of Jesus feeding a crowd with only five loaves of bread and two fish, as well as the ancient Greek story of Prometheus, whose liver was eaten out by an eagle every day, only to regenerate and be eaten again. Films like Cat Food prompted Hollis Frampton to opine, “The thought of some Purgatory wherein I might be deprived of seeing Joyce Wieland’s films makes me regret my every sin and dereliction.”

Hollis Frampton, Carrots and Peas (1969) (5 minutes)

Carrots and Peas is a cinematic still life in which images of the titular vegetables are paired with the voice from an exercise film played in reverse. Early in the film, Frampton manipulates the imagery by flipping it upside down, adding a color filter, and painting the filmstrip itself. As the film continues, however, the interventions cease, and the viewer ends up staring at a single static image of carrots and peas for a prolonged period of time. Once this happens, one begins to notice details of the shot had originally escaped one’s attention: the indentations on individual peas, for example—or the way one carrot slice seems to be hiding from the others. Carrots and Peas is so odd and inexplicable, it makes me giggle with glee.

Norman McLaren, Synchromy (1971) (7 minutes)

To create this exuberant abstract film, McLaren photographed striated cards with colorful lines on them and placed them onto the film’s soundtrack to produce a series of specific pitches. McLaren then placed these same cards onto the film’s visual track, thus creating a precise synchronization of sound and image. The result is an orgy of color and sound, an exhilarating experiment in cinematic synesthesia.

Naomi Uman, removed (1999) (7 minutes) (NSFW)

Uman erases the women from an old pornographic film using nail polish and bleach, and the result is a provocative and playful deconstruction of cinema’s representational codes. Uman invites viewers to do whatever they want with these “holes.” One can attempt to “peek” at the women who are being erased (since they occasionally become visible, in whole or in part, for a split second). One can enjoy the absences as absences, taking pleasure in the film’s shimmering voids. Or one can fill in the blanks with one’s own desiderata. In the words of Claire Stewart, “The hole in the film becomes an erotic zone, a blank on which a fantasy body is projected.”

Enter our SCMS 2020 drawing for a chance to win a free book. Although we encourage you to buy from your local bookstores, we are offering a 30 percent conference discount when you order from our website. Use coupon code SCMS20 at checkout to save on our SCMS books on display .

Categories: Film Media Studies Society For Cinema and Media Studies Virtual Exhibits

Tags: Absense in Cinema Justin Remes Motion(less) Pictures SCMS2020

Related Posts

Comedies of Catastrophe, Contagion, and Self-Quarantine: A Spectral Playlist for the Impromptu Apocalypse

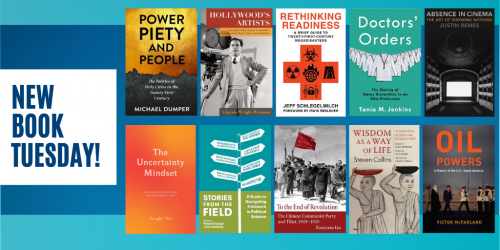

New Book Tuesday! Rethinking Readiness, Doctors’ Orders, Stories from the Field, and More!

Q&A: Claudia Breger on Making Worlds , and What Films to Watch While Social Distancing

There’s More to 3D Than Meets the Eye By Nick Jones

Join Ryan Groendyk in a Conversation About Wallflower

New Books in Film and Media Studies from Auteur, transcript publishing, and the Austrian Film Museum

Chromatic Modernity Wins the Katherine Singer Kovács Book Award!

Anxious Afterthoughts on Anxious Cinephilia by Sarah Keller

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This website uses cookies as well as similar tools and technologies to understand visitors’ experiences. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University Press’ usage of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Press Blog Cookie Notice .