An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Violence Against Women in India: An Analysis of Correlates of Domestic Violence and Barriers and Facilitators of Access to Resources for Support

Bushra sabri, arthi rameshkumar.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Bushra Sabri, School of Nursing, 525 North Wolfe Street, Room N530L, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD-21205. Contact: [email protected] ; Twitter: @bushrasabri. Phone: 410-955-7105

Issue date 2022.

Domestic violence (DV) is a significant public health problem in India, with women disproportionately impacted. This study a) identified risk and protective correlates of DV and, b) barriers and facilitators for seeking and receiving help for DV among women in India.

A systematic search of 5 databases was performed to identify correlates of DV in the quantitative literature. The search resulted in inclusion of 68 studies for synthesis. For qualitative exploration, data were collected from 27 women in India.

While factors such as social norms and attitudes supportive of DV were both risk correlates and barriers to addressing DV, omen’s empowerment, financial independence and informal sources of support were both protective correlates of DV as well as facilitators in addressing DV.

Conclusions:

Strong efforts in India are needed to reduce DV-related risk factors and strengthen protective factors and enhance access to care for women in abusive relationships.

Keywords: Domestic violence, women, help-seeking, resources

Domestic violence (DV) is a global social problem with devastating physical and mental health effects on individuals experiencing victimization. India suffers a high burden of DV against women. In the 2019-2021 India National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 32% of ever-married women in India reported experiencing physical, sexual, or emotional violence by their current or former husband. Women’s experiences of any DV varied across states or union territories, with the highest prevalence in the southern state of Karnataka (48%) ( International Institute of Population Sciences, 2022 ). According to the National Crime Records Bureau (2019) report, approximately 31% of the cases reported under crimes against women were classified under DV (i.e., the category of cruelty by husbands or his relatives). A systematic review of 137 quantitative studies examining DV experiences of Indian women identified that median and range of lifetime estimates of multiple forms of DV among women were 41% (18-75%) and past year estimates were 30% (4-56%) ( Kalokhe et al., 2017 ). Of note is that women in rural areas were more likely than those in urban areas to experience DV victimization (36% versus 28%) ( International Institute of Population Services, 2017 ).

DV has been defined as “all acts of physical, sexual, psychological or economic violence that occur within the family or domestic unit or between former or current spouses or partners, whether or not the perpetrator shares or has shared the same residence with the victim” ( Chernikov & Goncharenko, 2021 ; p.811). The United Nations defines DV as a “pattern of behavior in any relationship that is used to gain or maintain power and control over any intimate partner.” “This includes any behaviors that frighten, intimidate, terrorize, manipulate, hurt, humiliate, blame, injure, or wound someone” ( United Nations, n.d. ; 1 st para). In India, the definition of DV under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (PWDVA) (2005) is in consonance with the UN definition of DV. DV in Indian context is defined as “harming, injuring, or endangering the health, safety, life, limb or well-being, whether mental or physical, of the aggrieved person” ( The Gazette of India, 2005 ; p. 3). Similar to the UN definition, the definition of DV in India includes actual or the threat of physical, sexual, economic and/or psychological harm perpetrated on the woman by her spouse or intimate partner ( The Gazette of India, 2005 ). However, the perpetrators of DV in Indian context expands the global definition to include both spouse and/or in-laws ( Sabri et al., 2015 ; Sabri & Young, 2021 ). Additional behaviors included in DV in India are honor killings, unwarranted dowry demands and related harassment by husband and/or in-laws ( Bhandari & Hughes, 2017 ; Sabri et al., 2015 ; Sabri & Young, 2021 ; The Gazette of India, 2005 ). Entrenched patriarchy, rigid gender norms and unequal power and control between spouses are some of the factors that play a role in perpetration of DV by the spouse and/or by spouse’s family members (i.e., in-laws) ( Bhandari & Hughes, 2017 ; Rai & Choi, 2021 ; Ragavan & Iyengar, 2020 ; Sabri & Young, 2021 ). DV has a devastating impact on physical and mental health of women. Furthermore, experiences of DV are associated with prolonged trauma, decreased self-worth, emotional distress ( Campbell, 2002 ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008 ; Sabri et al., 2014 ) and extreme consequences such as, homicides and suicides ( Sabri et al., 2015 ; Sabri & Young, 2021 ). A large number of DV-related deaths have been reported in India, with most frequently identified motive being dowry demands followed by a history of DV or harassment and family conflict ( Sabri et al., 2015 ).

Correlates of Domestic Violence

Identifying correlates of DV can be useful for developing prevention and intervention efforts for DV in India. Research has associated several factors operating at multiple levels of the socio-ecological model (societal, community, relationship, and individual) with DV among women (World Health Organization (WHO), 2020). In the Indian context, the correlates of DV at the societal level include patriarchal attitudes and beliefs, social and cultural norms (e.g., dowry) as well as justification of violence against women when they deviate from gender inequitable norms ( Koenig et al., 2006 ; Sabri et al., 2015 ; Sabri et al., 2021 ). At the community level, residence in slums with concentrated poverty, stigma of DV, and limited access to resources can enhance women’s exposures to DV ( Sabri & Campbell, 2015 ). Gender-role expectations and partner/husband’s and in-laws’ characteristics and behaviors (e.g., husband’s controlling behavior, both emotional and financial, ( Bhandari & Hughes, 2017 ; Dalal & Lindqvist, 2012 ) are examples of factors at the relationship level and personal history factors, such as low socio-economic status are factors at the individual level ( Sabri et al., 2014 ; Sabri et al 2021 ).

Barriers and Facilitators of Help-seeking or Addressing Abuse

Despite the high prevalence estimates of DV, there is under-reporting of cases of DV in India. Culturally, women bear the burden of upholding family values and honor. The importance of keeping family consistency, honor and preserving the public image of a happy, healthy, and successful family, can lead to underreporting of DV by survivors ( Husain, 2019 ). The Indian cultural values as well as perception of DV as more of a private or family matter ( Nigam, 2017 ) impact reporting or help-seeking as well as receiving help for abuse. The rigid gender-roles for men and women, and patriarchal values can cause women to occupy a lower social standing compared to men ( Rai & Choi, 2021 ; Rai, 2020 ; Panchanadeswaran & Koverola, 2005 ; Sabri, Simonet et al., 2018 ; Sabri, 2014 ). This lower status is one of the barriers to help-seeking. Marriage in the Indian community is distinct from the American culture, which is a union of families rather than two individuals. Often the couple has had limited contact prior to the marriage festivities ( Sharma et al.,2013 ). The salience of family honor (Izzat) and the expectations attached to being a good daughter-in-law can deter women from disclosing matters relating to domestic abuse outside of the home, further reducing the likelihood of seeking help ( Gangoli & Rew, 2011 ; Mahapatra & Rai, 2019 ; Raghavan & Iyengar, 2020 ). Living in joint families with in-laws may also be a risk factor due to high instances of in-laws’ abuse, therefore living separately from in-laws may serve as a protective factor in certain cases where partner is not abusive and only in-laws are abusive ( Raj et al., 2011 ; Ragavan & Iyengar, 2020 ; Rai, 2020 ; Vindhya, 2007 ). In-laws’ behaviors such as instigating fights between the couple have also been found to contribute to abuse of women by a partner ( Sabri & Young, 2021 ).

Even with regards to help-seeking, informal help-seeking through friends and family members is more common than formal help-seeking through DV agencies or other professionals ( Decker et al., 2013 ; Mahapatro & Gupta; 2014 ). According to the NFHS-4 data, about 86% of women in India who experienced DV victimization did not seek help and about 77% of them did not mention the incident to anyone ( International Institute of Population Services, 2017 ). Among the 14.3% of women who did seek help, 7% sought formal help through authorities, the police, lawyers, and social service agencies, whereas 90% of those who sought help received it from their immediate family ( International Institute of Population Services, 2017 ).

Study Rationale

Drawing from the socio-ecological model (World Health Organization, WHO, 2021), we conducted a systematic review to examine factors at multiple levels that shape risk and protective factors for DV as well as influence help seeking and access to services. The socio-ecological model is a prevention framework that can help identify factors at various levels: societal, socio-cultural, community, relationship, and individual, while informing prevention approaches. This model accounts for the interplay of factors at various levels and allows us to “understand the range of factors that put people at risk for violence or protect them from experiencing or perpetrating it” ( CDC, n.d. , 2 nd para, WHO, 2021).

Relying on the socio-ecological framework, the literature for the systematic review was compiled to identify most frequently reported risk and protective correlates. The goal was to move beyond static (unchangeable) risk factors to identify dynamic (or changeable) risk and protective factors or actions that can decrease risk for women. For example, dynamic risk factors such as alcohol or drug use or hesitancy to seek help, can be addressed by reducing alcohol or drug use ( Dutta et al., 2016 ; Mahapatro et al., 2012 ), and promoting help seeking which may have a strong protective effect against DV. Findings from the existing literature on dynamic risk and protective factors can be part of safety planning interventions for abused women in India. Many studies have examined correlates of DV in India. However, there has not been a systematic review of quantitative literature identifying risk and protective correlates of DV at multiple levels of the socio-ecological model. Further, although studies have examined patterns of help-seeking among abused women in India, to the best of our knowledge, studies have not explored barriers and facilitators of help-seeking or addressing DV among women using a socio-ecological approach. Therefore, the present study adds to the existing literature on DV in India by conducting a systematic review and a qualitative study to examine a) risk and protective correlates of DV, and b) barriers and facilitators for help-seeking or addressing abuse among women in India at the socio-cultural, community, and individual levels.

While the systematic review of quantitative studies helped identify correlates of DV to highlight groups at risk and factors that could be protective, the qualitative exploration identified barriers and facilitation of seeking and receiving help for DV. These two separate analyses could provide insight into the target areas of prevention and intervention collaboratively, as well as strategies to strengthen access to care among women in abusive relationships in India. The integration of these two strands of data is vital for not only identifying risk factors of victimization but for also highlighting barriers for help-seeking, that may collaboratively be discouraging women from seeking help. Victimization within Indian households can manifest in complex ways that is distinct from Western communities, therefore, merely examining risk factors without understanding barriers is only solving part of the problem. Through our integrated approach, we advance existing evidence by providing an insight into risk factors and barriers, that can both impede help-seeking.

Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies on Risk and Protective Factors for DV in India

To examine risk and protective correlates of DV, a systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols ( Moher et al., 2015 ). The PRISMA checklist ( Page et al., 2021 ) is included in appendix . The following databases were searched: PubMed New, CINAHL, Embase, Web of Science, and PsychInfo. The five databases were chosen in consultation with an experienced university librarian. The databases selected were identified as one of the most comprehensive social science databases for published peer-reviewed literature on the topic under investigation in this study. The terms related to correlates such as “risk,” “protective factors,” “barrier,” and “facilitator,” were combined using the Boolean connector “OR.” The violence-related terms such as “Domestic Violence” “Intimate Partner Violence” and “Battered women” were also connected using the Boolean connector “OR”. The terms related to correlates and violence and Indian setting (e.g., “India”) were combined using the Boolean connector “AND.” Detailed search terms are included in appendix .

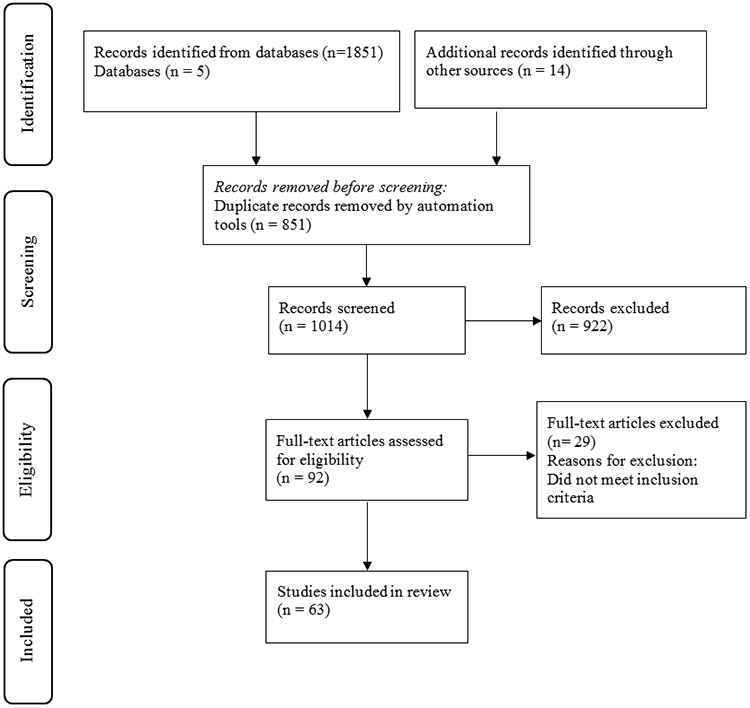

Peer reviewed studies were included if they were: 1) quantitative or mixed methods studies that reported quantitative findings, 2) included quantitative outcomes of domestic violence and/or examined correlates of DV, 3) were conducted in India, and 4) were published in English. Studies were eliminated if they: 1) did not report results on DV as an outcome, 2) were published before 2010, and 3) were only qualitative analyses or systematic and literature reviews. The articles were imported into Covidence ( Covidence Systematic Review Software, n.d. ), and duplicates were identified and removed. To reduce risk of bias, two members of the research team conducted independent screening of titles and abstracts for inclusion and exclusion. The full text of selected articles was thoroughly reviewed for data extraction. Any disagreements regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria and extracted data were discussed in individual meetings and resolved. Correlates of DV included factors at the socio-cultural, community and individual levels of the socio-ecological model such as availability of services, help seeking behaviors, safety strategies used by women, and beliefs and attitudes. Figure 1 presents the flowchart of the article selection process.

PRISMA Flow Diagram of Study Selection

Qualitative Exploration of Barriers and Facilitators for Help-seeking or Addressing Domestic Violence among Women in India

Qualitative data was collected from women survivors of DV from two regions in India: Delhi and Uttar Pradesh. Participants were recruited using purposive and snowball sampling techniques ( Trochim & Donnelly, 2008 ). Recruitment strategies included flyers, word of mouth, snowball sampling and assistance from a women’s health clinic in Delhi run by a non-profit called MAMTA Health Institute for Mother and Child. For eligibility, women had to be 18 years or older, in an intimate partner relationship for 6 months or more with a history of DV, and India as the country of birth. After obtaining oral consent, seventeen individual in-depth interviews and a focus group ( n =10) were conducted in-person using semi-structured interview and focus group guides, at a safe and convenient location for the participants. Women who participated in the focus group did not participate in the individual interviews. A trained doctoral-level interviewer conducted the focus group and interviews. Utilizing two data-gathering methods (focus group and interviews) enhanced the credibility and trustworthiness of our study findings. While focus groups were helpful in gaining insight into women’s shared understanding of issues related to DV, and group understanding of barriers and facilitators of women’s help seeking and access to resources, in-depth interviews provided a deeper understanding of women’s experiences, attitudes, and beliefs about DV and help seeking.

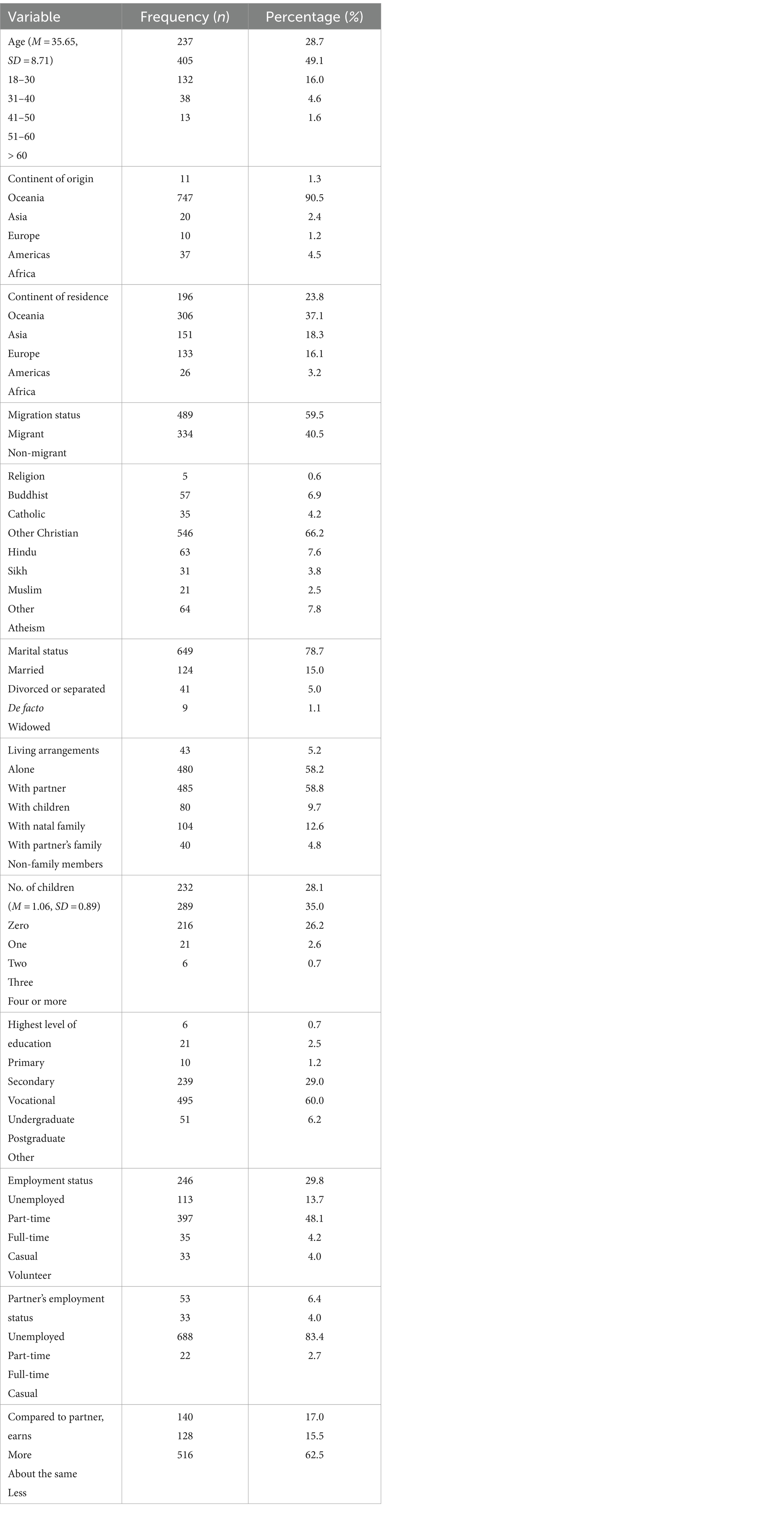

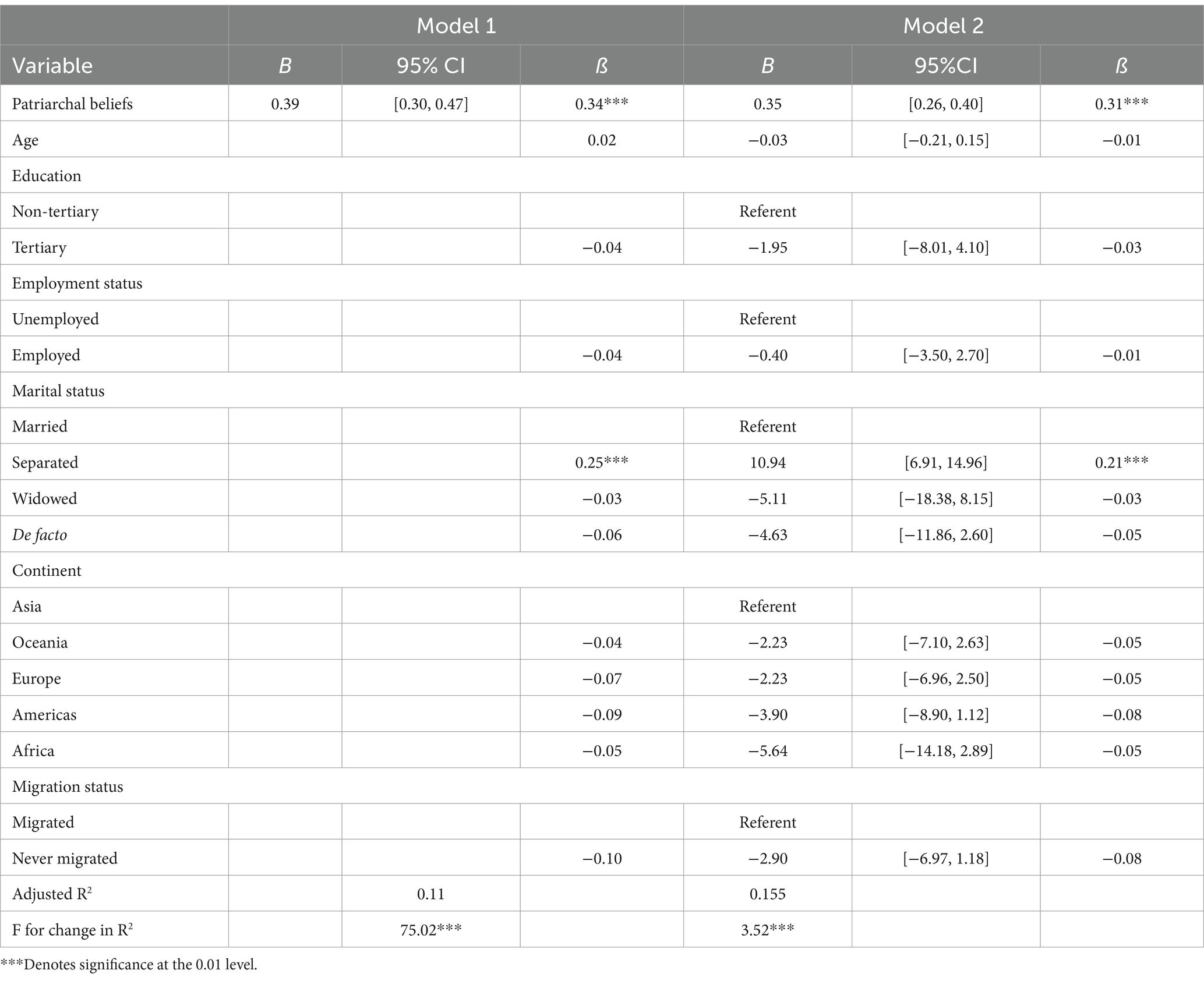

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1 . Participants ( n =27) were, on average, 34.6 years old ( SD =11.1). All participants reported being in a heterosexual relationship with an abusive male partner. Sixty-seven percent were married ( n =18), 29.6% ( n =8) were divorced or separated, and one woman was widowed, with average relationship length being 15.71 years ( SD =9.89). Most participants reported physical abuse (92.3%, n =24), sexual abuse (52%, n =13), and psychological abuse (95.5%, n =21). Only 11.1% ( n =3) completed high school, with remaining women educated under high school (48.1%, n =13) and 40.7% ( n =11) having no schooling or education. Our sample size of 27 participants was adequate to reach data saturation. Saturation was achieved when no new information or themes were identified ( Charmaz, 2006 ). The study was approved by the institutional review board of the home institution of the lead author (IRB00046370).

Participant Demographics

In the parent study, both the interview and focus group guides included questions on perceptions and experiences of abuse including risk factors for abuse, strategies and resources used for coping, help seeking patterns, needs for services and overall health. The quantitative questionnaires were used to collect information such as age, income, marital status, and level of education. The study completed data collection when it appeared saturation had been reached and there was no emergence of new findings. Both the focus group and the interview sessions lasted for 60-90 minutes. The sessions were audio-recorded using digital recorders. Data was collected in Hindi and the transcripts were translated and back translated in English ( Behr, 2017 ; Brislin, 1970 ). Each participant received Rs. 1400 (approx. 19.4 USD) for compensation of their time. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the primary author.

Data was analyzed using a hybrid process of deductive and inductive thematic analysis procedure underpinned by the socioecological framework identifying multilevel barriers and facilitators for help-seeking and addressing abuse. The process involved manually listing of a priori themes based on the socio-ecological framework, and independent coding of the transcripts by two coders (1 PhD level and 1 masters’ level coders), with simultaneous development of inductive themes in the process. Inconsistencies in coding and any discrepancies in content and meaning of each code was resolved in individual meetings. An audit trail through detailed notes of data collection experiences and thoughts, and analytic triangulation with the two coders established trustworthiness of the data (Saldana, 2013).

To identify commonalities in findings from the systematic review and the qualitative interviews, the quantitative and qualitative data was analyzed separately. This was followed by reviewing the content to identify similarities and differences in the barriers and facilitators of addressing abuse in the qualitative data and risk (barriers) and protective (facilitators) correlates of addressing DV in the systematic review. Since the purpose of analysis using the two sources of data was different, we identified commonalities in areas such as correlates of DV also being a barrier to addressing abuse of help seeking and protective factors identified in the systematic review also being a facilitator for addressing abuse of seeking help. For example, our systematic review findings identified attitudes supportive of IPV as a risk correlate for DV. Similarly, the qualitative findings revealed justification of wife beating as a barrier to help seeking or addressing abuse. Using a comparative method, we were able to compare findings across themes and the quantitative findings from the systematic review.

Systematic Review Findings

Risk and protective correlates of dv.

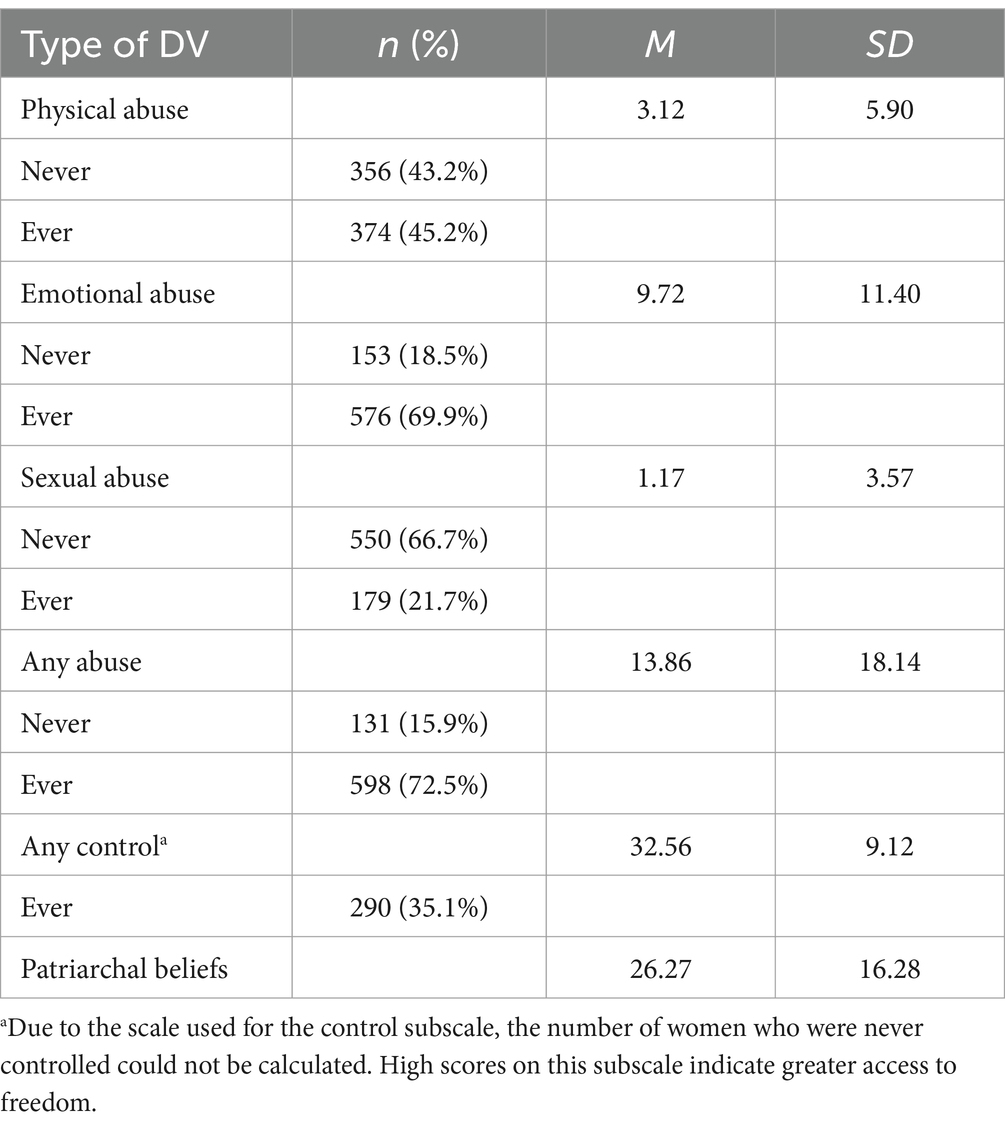

The initial search across the different databases identified 1851 articles, with additional 14 identified through hand searching the references in the retrieved articles. After removing duplicates ( n =851), 1014 abstracts and titles were screened for relevance. This screening resulted in 92 articles that were retained for full text review. After full text review, 63 articles were selected for inclusion and synthesis ( Figure 1 ). Drawing from the socio-ecological model, risk, and protective correlates of DV in the articles were identified at the socio-cultural, community, relationship or interpersonal and individual levels ( Table 2 ). The most frequently reported risk correlates of DV at the sociocultural level were norms and attitudes that supported violence against women, male dominance, and ideals of masculinity ( n =13). Further, cultural practice of dowry, where husband/in-laws were dissatisfied with the dowry amount ( n =6) also resulted in increased DV and women’s deaths. At the interpersonal level, the most frequently reported risk correlates of DV were partner’s characteristics such as alcohol dependence, smoking, substance abuse and/or gambling/betting practices ( n =32). Other partner characteristics associated with DV included their low education ( n =10), unemployment or having an unskilled occupation ( n =9) and controlling behaviors ( n =8). A larger family with more children ( n =11) was also associated with increased risk for DV. At the individual level, the most frequently reported correlates that were associated with enhanced risk for DV were women being employed or having higher earnings than their partner ( n =21), women coming from a low socioeconomic status or standard of living ( n =18), having no or low education ( n =17), being married at a younger age (<18 years, n =9) and living in a rural setting ( n =7). The findings on education were mixed with some studies ( n =5) reporting that women’s higher education was associated with their greater exposure to DV and others reporting no or low education as a risk factor for DV. Other reported correlates associated with enhanced risk for DV included women’s HIV positive status, and childhood exposures to DV.

Findings from the Systematic Review

Achchappa, et al., 2017

Ahmad & Mozumdar, 2019

Babu & Kar,2010

Babu, G. & Babu, B.

Begum et al., 2015

Biswas, 2016

Borah et al., 2017

Bourey et al., 2013

Hayes & Franklin, 2016

Chakraborty et al., 2016

Chibber et al., 2012

Dalal, 2011

Dalal & Lindqvist, 2012

Das et al., 2013

Das et al., 2018

Das & Roy, 2020

Dasgupta, 2015

Dasgupta, 2019

Donta et al., 2016

Gaikwad & Rao, 2014

Gupta et al., 2019

Hackett, 2011

Hartmann et al., 2020

Jain et al., 2017

Jayaram et al., 2014

Kalokhe et al., 2018a

Kalokhe et al., 2018b

Khandare, 2017

Kimuna et al., 2013

Krishnamoorthy et al., 2020

Krishnan et al., 2010

Ler et al., 2020

Madhivanan et al., 2014

Mahapatro et al., 2011

Manohar & Kannappan., 2010 .

Mathew et al., 2019

Mehta et al., 2019

Mukherjee & Joshi, 2019

Murugan et al., 2020

Naveen Kumar et al., 2012

Patrikar et al., 2017

Patrikar et al., 2012

Raj et al., 2010

Raj et al., 2018

Ram et al., 2019

Reed et al., 2015

Sabarwal et al., 2014

Sabri et al., 2014

Sabri et al., 2015

Showalter et al., 2020

Shrivastava, P.S., & Shrivastava, S.R., 2013

Simister & Mehta, 2010

Singh et al., 2014

Sinha et al., 2012

Sinha & Kumar, 2020

Stanley, 2012

Subodh et al., 2014

Thomas, 2020

Thirumalai, 2017

Weitzman, 2020

Zhu & Dalal, 2010

The systematic review was also used to identify correlates at different levels that could protect women from DV or prevent future DV. At the sociocultural and community levels, greater gender equity ideologies ( n =1), and wife’s social support from the community ( n =1) respectively, were found to be protective against women’s victimization by DV. At the interpersonal/relationship level, empowerment where wives had joint control of partner’s income and made joint household decisions ( n =5) were significant protective factors. At the individual level, women who had higher education ( n =12), were married at >18 years of age ( n =5), were empowered in household decision making, had sexual and financial autonomy and freedom of movement ( n =7), were employed, or had higher earnings than their partner ( n =5), and who came from higher socioeconomic statuses were at a reduced risk of DV.

Although the findings on correlates such as women’s education and empowerment were mixed with these correlates reported as risk correlates in some studies and protective correlates in other studies, most studies reported these as protective. For example, empowerment in household decision making, financial and sexual autonomy, and freedom of movement was more frequently reported as protective ( n =7) than as a risk factor for DV( n =5). Similarly, a woman’s higher education was more frequently reported as protective ( n =12) than a factor that enhanced risk for DV ( n =5). However, most studies reported women’s employment being significantly associated with increased DV ( n =21) than reducing the risk for DV ( n =5).

Qualitative Findings

Barriers for seeking or receiving help for dv.

At the socio-cultural level, adherence to patriarchal norms, family honor and justification of wife beating were barriers to seeking or receiving help for DV. At the community level, factors related to police involvement and inadequate help from police were significant barriers. At the relationship level, family obligations were a barrier. Barriers at the individual level was identified as learned helplessness ( Table 3 ).

Participant Quotes

Patriarchal Norms and Justification of Wife Beating.

Some women ( n =5) did not seek help for abuse or try to help other women facing abuse because of their justification of wife beating. Being raised in a society with strict gender norms, abuse was normalized in their families. Overall adherence to such norms was also a barrier to women receiving help for abuse: Problems happen because no one listens to the woman (Participant 2).

Commonly identified reasons for justification of abuse by women were if a woman is having an affair, not taking care of her family, talking back to her husband or in-laws, spending money, or making any mistake. One participant justified that it was acceptable for men to mildly abuse their wives during an argument and that the wife should not argue back to prevent further abuse. These participants felt that if the woman made no mistake, then the abuse was unacceptable. For example, a participant shared:

If the wife does something wrong. Like if she goes in the wrong road, or if she is using up the money for expenses, or if she is not fulfilling her responsibilities in the house. Then, the husband is compelled to hit her. Then he’s right to hit her because it’s for a reason. Then it’s fine (Participant 14).

Need to Protect Family Honor.

Family honor prevented some women ( n =4) from seeking help for abuse. Stigma of IPV and blaming the woman and her parents for her abusive situation led women to continue to endure abuse and kept them from seeking help. One participant stated that:

My parents had told me that whoever I marry, with honor I have to spend the rest of my life with him, and so it was nothing but this honor that I was after… I’m not afraid of people. I just want to maintain the honor of my maternal home, my parents, and my in-laws (Participant 1).

One participant described how her mother talked to her about staying in a marriage because that was essential for a girl to live a fulfilled life.

My mother would tell me before marriage, that I should be able to tolerate. I should remember that I need to stay with my husband for the rest of my life, whether it’s for better or for worse. If a woman considers her husband her life, she will have a fulfilled life (Participant 4).

Lack of parents’ support and their need to protect their image in the community was also a barrier to addressing abuse: Three times I came home. They [parents] tried to convince me and then sent me back (Participant 14).

Perceptions of the Police.

When asked about asking police for help, some women identified that if the abuse was severe or if they felt that their life was in danger, then they should contact the police. However, the same women ( n =6) shared their hesitancy in reaching out to the police. One factor was the perception that their situation did not warrant police involvement: So much has happened to me, but even then, I didn’t call the police (Participant 1). Another participant stated: Someone who is fed up with her husband would call the police. But even in a situation like that, no one calls the police (Participant 9). Lack of courage was another barrier: Many times, I thought I should get him beaten a little by the police; that would straighten him up. But I never got the courage (Participant 10).

Two participants identified lack of trust in the police and legal system, stating that money played a huge factor in whether their complaints were taken seriously. Anywhere you go, people just listen to money. Whether it be at the police station, or anything, you just give them money and tell them what to do and they do it. No one listened to me (Participant 2).

Similarly, another participant cited how she did file a formal complaint, but her husband and his family had bribed the police, so she never received any help: We went to the police station. I put in an application here, and then they buried it for 20,000 rupees (approx. 265.9 USD) (Participant 5).

Fear of retaliation from the abuser was another barrier. For some women abuse increase with reporting: I had the letter the police wrote. I could not file a complaint because my husband could be at the police station waiting for me. He would just beat me and drag me back to his home (Participant 5).

Family Obligations.

Some women ( n =2) reported staying in their abusive marriages and not seeking help because of their children and the perception that leaving the abuser will only hurt the children. Their children were dependent on them and would need their father for financial support.

I left so many times. Sometimes for 15 days at a time to a month, I would go stay with my mother. I planned on leaving him, I even told them to bring my children to me, but then I kept going back for my children. (Participant 11)

Another woman identified how she lost her individuality and had to change her life to suit her family obligation. She was not independent because she had to be there for her children, and husband. As a result, she was not able to pursue a career or support herself, which was a barrier to seeking help for abuse in marriage: I realized that I live for my children and husband, so I have to compromise to be with them. Before I thought I could earn myself and live on my own, but that’s no more (Participant 3).

Learned Helplessness.

Several women ( n =5) were not able to seek help or leave their abuse because of their learned helplessness. Because they have endured abuse for so long and have not been able to change their current situation, they did not try to seek help. Additionally, the way they coped with the abuse prevented them from seeking help. Not feeling empowered or strong enough has forced them to stay in the relationship with their abuser. One participant felt that her life was unsuccessful and lost faith in other possibilities: Why would I call this life successful? When I’ve endured so much, what is left (Participant 1)? Four women specifically cited how their timid and obedient personality prevented them from standing up for themselves. These women were not as confident and accepted that this was their life. For example, a participant shared: I kept everything within me. I think about things, but I don’t respond to anything, regardless of how anyone treats me. I’m very timid (Participant 2).

One participant was never supported by her neighbors or people who witnessed the abuse. This discouraged her and prevented her from helping herself as well as other women who could be experiencing abuse: When I was being beaten, the people at home would look on and laugh at me, so why would I do anything for anyone else. The neighbors would look at the spectacle, as if it’s something I deserve (Participant 1).

Facilitators for Seeking or Receiving Help for DV

Participants shared that factors that facilitated help seeking and receiving help for abusive situations involved available resources in the community, support from family, friends and neighbors and economic independence. Other facilitators of addressing abuse were women’s own strengths and use of religion or faith to cope with abusive situations.

Community Resources.

According to participants ( n =4), having support from the community and government could help them become economically independent, empowered, and provide an opportunity to live abuse-free lives. A participant highlighted the need for services for safety: There is so much persecution of women, so services should definitely be there… the government should do something to make us safe (Participant 3). Another participant stated that the services should focus on abuser’s behavior as well as supporting the woman being abused:

There should be help for women whose husbands abuse them. They should teach the husbands. For some days, they should lock them up and beat them, so they understand what the pain is like. And since he threatens to leave me, there should be endeavors like MAMTA (non-profit) to help women. If he tells me to leave, then I have somewhere to go where they would help me. (Participant 4)

Financial stress in the family being a significant risk factor for abuse of women, a need was highlighted for policies to meet basic needs:

The government should provide services to help unemployed men get jobs. There should also be services to help pay the fees for children’s education and give jobs to those providing for children. Children should also receive uniforms from the government to attend school. (Participant 3)

Although there was hesitancy in reaching out to the police for help, one participant stated how important it is for women in abusive relationships to get the police involved in order to find a solution to their problem:

She should file a complaint with the police. There are a lot of women who have this problem, and it’s been solved. The police can figure out what the fight is about, and can talk to them both and find the problem. (Participant 12)

Support from Family, Friends and Neighbors.

Although, there were instances when women in abusive relationships were not supported by their family and friends due to family honor or societal expectations, still several women ( n =10) experienced support from their parents, siblings, and friends. This support was perceived as important for these women because their parents could question their husbands and his family, provide her shelter when the abuse was unbearable, and allowed her to seek help.

Contrary to what some women said about family honor and expectations, this participant stated:

My family hasn’t changed at all. They are exactly as they were before. They try to support me as much as possible. They never make me feel like I’m an outsider after marriage. They will do whatever I need, I just need to tell them. I am not forced to do anything. (Participant 5)

Family was a source of resilience and empowerment:

My family was with me. They supported me through everything. Whenever I told them anything, they said to leave, get educated and become independent (Participant 6).Another participant also stated how her parents supported her by providing her with money and supplies for her and her children while she was with her husband: Whenever something happened, Mummy and Papa would do something such as getting me money, or if the children needed clothes, then Mummy and Papa would get that done for them. My husband did nothing (Participant 14).

For one woman, getting her family involved helped stop the abuse:

My dad sent them a notice saying that if my sister-in-law or mother-in-law hit me, or if anything happened to me, then they [in-laws] would be responsible. He would send me back if they signed the notice. Then they stopped hitting me. (Participant 3)

Additionally, friends have been a source of moral support helping women build the strength to stand up for themselves and finding resources to support them. My friend told me to fight and stay happy. Whatever happened, happened, but the future shouldn’t be worsened by it. You only get one life. I share everything with him, and he gives me the strength to fight (Participant 2).

In some cases, neighbors and people outside the family intervened to help women being abused: Some people would see him hitting me with a slipper and snatched the slipper away from him. A few other people, when they saw him insulting me, they would come between us and save me (Participant 1).

Economic Independence.

Women expressed that economic dependence and poverty were one of the main reasons why they continued to endure abuse in marriages. Financial independence ( n =2) was perceived as a factor in ability to address abuse:

It doesn’t matter that my husband doesn’t give me money, because I can work hard and earn my own money. In Delhi (India), no one stays hungry, people work hard and earn their food, they’ll do anything like scrubbing people’s floors. (Participant 1)

Another participant believed that economic independence could protect her from her abuser: I’m good at cooking, and I know how to do beauty parlor work very well. I feel like the day I try doing a job, I’ll save myself from him (Participant 2).

Inner Strengths.

Although learned helplessness prevented women from seeking help, women who were empowered and more resilient were able to leave their abuser ( n =4). They were able to stand up for themselves and face the challenges in their lives. One participant stated that she felt she was resilient and strong enough to face her issues. She also had the confidence in her abilities and her role as a mother and wife: I take responsibility for my children. I fulfill my duties as a wife in society. I have the strength to fight life’s problems (Participant 3).

When asked what advice they had for other women, three participants who left their abuser stated very strongly that women have rights as well and a sense of individuality. They deserved justice, and these participants felt that women need to stand up for themselves. They supported women becoming more resilient and empowered, so they did not have to keep enduring their abuse. For example, one participant stated.

I would say that women should stand up for themselves. These days, men aren’t everything, women also have a voice. They need to take their rights. They should stand up against the things happening to them, so that the same things don’t happen to other people (Participant 2).

Another participant echoed the same sentiment: She shouldn’t tolerate the injustice. She should become independent. It depends on the husband’s temperament; we can’t say anything about him. I have no idea how to handle that (Participant 6).

One participant shared how her urge to be independent and support herself and her children led her to seek help through a center (non-profit organization) for support. It was important for her to have her own source of income and she was empowered enough to seek that support.

I went to the center because regardless of whether my husband liked it or not, I wanted to be able to stand on my own two feet. Once I am independent, I won’t listen to anyone, I won’t be backed into a corner. I’ll be able to feed my own children. That’s why I went to the center and learned to sew (Participant 4).

Religion or Faith.

Religions and faith were strong factors in how women coped with their abuse. Additionally, many women ( n =8) said that religion and their faith was a source of happiness and strength and offered other women to turn to their faith as advice. These participants stated how God gave them the strength to endure the challenges they faced with their abuser and his family. They believed that praying would eventually stop their abuse and lessen their problems. Religion helped these women stay grounded and, in some situations, it was a source of resilience for these women. For example, a participant shared.

It is only because of my courage that I’m able to survive on my own, otherwise I don’t have a father’s or mother’s or anyone’s support. It’s only because God has given me so much courage, that I can survive on my own (Participant 1).

When asked if they have advice for other women experiencing abuse or ways to help them, women also suggested that faith and prayer will help them with their problems: I should tell her my solutions. I would talk to her about my problems and how I dealt with it. You never know, Allah may remove all her problems as well (Participant 9).

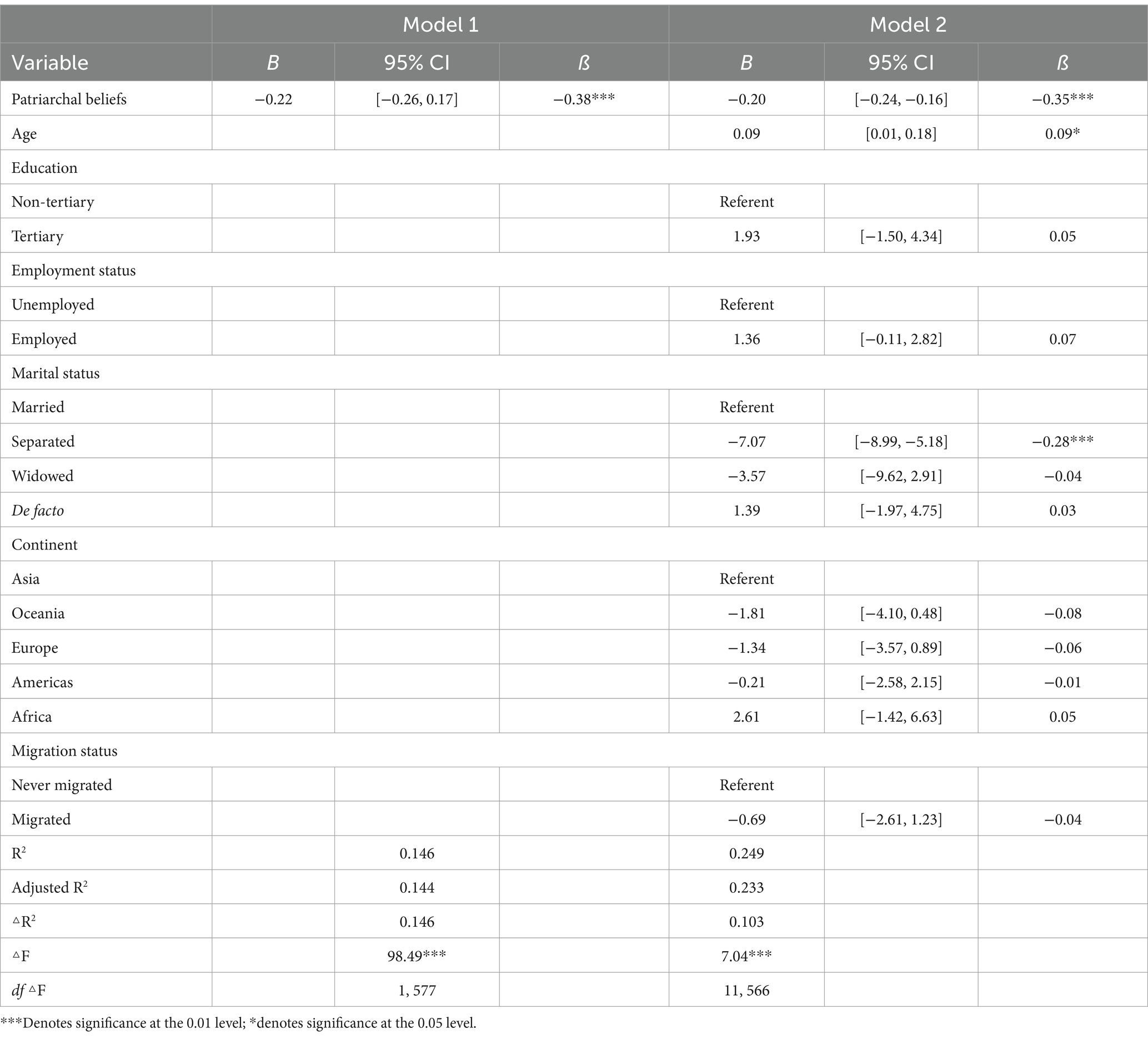

We will now discuss our findings from both the systematic review and qualitative data utilizing a socio-ecological framework. Interestingly, in our systematic review, economic independence was a risk factor of DV victimization at the individual level. While economic independence can help women break free from abuse, women’s employment was the most frequently reported factor that was associated with women’s experiences of DV. in the quantitative literature. Since we could not establish cause and effect due to cross-sectional nature of the studies reviewed, it is possible that DV may have caused some women to secure employment as a means of financial support. For employment to serve a protective role, there is need for awareness and modified cultural norms against rigid gender roles ( Dalal, 2011 ; Sabri et al., 2014 ). We also noticed that partner’s addiction (e.g., substance abuse), controlling behaviors and having more children in the family were the most frequently reported correlates of DV at the interpersonal level. Partner’s problem with addiction, financial stress along with the responsibility of large number of children in the family as an added source of stress can further contribute to DV in families as seen in previous research ( Campbell et al., 2003 ; Sabri, Nnawulezi, et al 2018 ).

In our qualitative analysis, we found barriers and facilitators of women’s help-seeking or confronting abuse. Some of these were adherence to patriarchal norms and justification of wife beating. Similar factors of supporting male dominance and attitudes supportive of violence against women, were also found to be significantly associated with enhanced risk for DV in the quantitative literature. Violence normalized as an everyday occurrence is a part of patriarchal ideology prominent in the Indian society, which impacts women’s willingness to address abuse in their lives. Further, in a collectivist society such as India, the norms and ideals surrounding appropriate behaviors and roles of women are often associated with the honor and reputation of the entire family ( Stephens & Eaton, 2020 ). Thus, many women continue experiencing abuse in the name of protecting family honor or Izzat ( Sabri & Young, 2021 ).

We observed thorough our qualitative findings that hesitancy to involve police was found to be an additional barrier to help-seeking. One of the reasons for hesitancy was inadequate response of the police including failure to act against the perpetrators and/or dismissing complaints through bribery. The findings on hesitance to call the police are similar to survivors of DV in other countries, including the U.S. ( Hayes, 2013 ; Rai et al., 2022 ; Yoshihama et al., 2013). Women may not seek help because of the fear of repercussions of involving the police or due to minimization of DV by the police. Further, focus of the criminal justice/law enforcement system on isolated incidents do not capture the complexities of DV situations and how ongoing power and control and other systems of oppression can impact women in abusive relationships ( Hayes, 2013 ). This incident-based focus of the police can be a barrier to help for women who have been living in abusive environments, with lack of support from their families and communities. The lack of support and inadequate help from the police can also be attributed to norms and attitudes that support male dominance in the family and normalize DV as a family matter (one of the risk correlates identified in our systematic review of quantitative literature).

In the qualitative analysis, facilitators of addressing abuse were found to be access to community resources such as resources for economic empowerment, and social support. Other facilitators of addressing abuse were women’s own strengths and use of religion/faith to cope with abusive situations. In the systematic review, women’s high education, empowerment, financial and sexual autonomy, joint household decision making, and high socio-economic status were protective factors against abuse. Social support from neighbors and family were also additional protective factors. Both external and internal sources such as support from family, friends, and neighbors as well as religious faith and beliefs have also been found to help abused women in other cultures or countries of origin ( Sabri et al, 2020 ). Thus, key components needed for intervening with abused women in India are programs facilitating overall empowerment including economic independence and encouraging women to access trusted informal sources of support for safety. These components were identified as common protective factors in both our systematic review of existing literature and the analysis of qualitative data ( Figure 2 ).

An Ecological Framework of Common Risk and Protective Correlates of Domestic Violence in both Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

Strengths and Limitations

An important strength of this study lies in its ability to summarize the correlates of DV, while simultaneously drawing from qualitative experiences about help-seeking. Despite the novel contributions of this research, there are some limitations associated with it. The qualitative portion of the study being limited to northern region of India may impact the transferability of the study results given the geographical and cultural diversity across India. However, the quantitative portion was not limited to any geographical region and used findings across India which strengthens our findings. Systematic reviews while rigorous are associated with the subjectivity of the research team. However, we maintained a detailed record of the decision points for included versus excluded studies for complete transparency. Lastly, multiple points of data are needed to establish consistency of barriers and facilitators for help-seeking which is also a limitation. Notwithstanding the limitations of this study, it is the first one to present findings by drawing from a systematic review and qualitative interviews about the risk and protective factors of DV and barriers and facilitators of help-seeking among Indian women, adding to the new evidence.

Implications for Research and Practice

There is need for additional research with participants across India to have a broader regional representation of barriers and facilitators of addressing abuse among families. Further studies are needed to assess risk and protective factors of DV in under-researched regions in India. Focus group interviews or observations with service providers can also impart a depth of information regarding experiences of abuse. Triangulating information through multiple sources of data collection can be pivotal in strengthening findings. It would also be helpful for scholars in the future to explore the grey literature including agency and other technical reports to investigate the risk and protective factors relating to abuse.

Our findings on risk and protective correlates of DV at multiple levels of the socio-ecology highlight the need for evidence-based DV prevention and intervention approaches to be implemented at multiple levels (e.g., community, society, family) in India. There is a need for approaches that address multiple drivers of DV such as gender inequality and partner’s addiction problem, including the most important drivers of DV in women’s lives. Recent reviews of literature on global interventions identified multiple drivers of violence against women as one of the key characteristics of successful interventions ( Kerr-Wilson, 2020 ). Moreover, the programs could incorporate training of healthcare providers, law enforcement professionals and other providers who encounter survivors of DV so that they can provide trauma-informed services to meet survivors’ needs.

Given the study findings, it is evident that there is an urgent need for change in social norms and practices that promote violence against women. Some study participants described family to be a protective factor and a source of support. Others described family as a deterrent by not allowing women to escape DV. This calls for culturally informed family and community-based intervention programs that address norms promoting gender inequalities and cultural normalization of abuse. Similar interventions have been developed for the South Asian community in other countries including the U.S. (e.g., Yoshihama et al., 2011 ; Yoshihama & Tolman, 2015). Engaging with family members along with survivors of DV is necessary for a large-scale shift in gender-inequitable norms, norms that place burden of family stability only on women, and norms that dissuade help-seeking. Developing interventions to have conversations around DV and ways in which family members can support individuals experiencing DV can be important in providing timely support to survivors. Bystanders can play an active role in providing support to survivors of DV and encouraging survivors to seek help. Additionally due to the importance of religion in South Asian culture and our findings on religion being a protective factor, faith-based interventions are needed that engage religious leaders in spreading community awareness around issues of DV ( Sabri et al., 2018 ). Interventions addressing traditional gender role expectations without threatening the husband’s position in the family ( Sabri et al., 2018 ) can also play a role in reducing DV among families in India.

Financial independence can increase women’s ability to support themselves and their children once they decide to break free from an abusive relationship. Policies are needed to provide interest free student loans and caretaking facilities along with job assistance programs for women struggling to support themselves. It is also important for government agencies to introduce public provisions such as microfinance or small loans in conjunction with vocational training programs ( International Finance Corporation, 2018 ). Non-governmental organizations, supported by government as well as international funding, can be encouraged to provide livelihood training and employment opportunities to women in DV relationships, so that they have the financial independence and opportunity to escape abusive relationships.

Ultimately, it is vital for community agencies to make women aware of the laws concerning DV in India. There exist legal mechanisms such as the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 and the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961. Women experiencing DV may not be aware of the legal recourse available to them, therefore there is a sense of urgency in translating the policies to them. These efforts can be sustained through community awareness drives across India including rural and urban regions. Researchers and practitioners are encouraged to collaborate to engage with communities in unique ways to create awareness around these laws and reduce DV among Indian families.

The findings of our study highlight risk and protective factors of DV and barriers and facilitators of addressing DV. Our findings show that there is need to address risk factors and norms that promote violence against women at all sociological levels. For far too long, Indian women have succumbed to DV, therefore it is imperative for researchers and practitioners to collaboratively develop evidence-informed interventions to help shift harmful norms and address risk factors at multiple levels to reduce the risk of DV victimization. Efforts could be made to strengthen protective factors against DV and establish safe environments for women’s health, safety, and well-being. There is also need for efforts to address barriers and capitalize on the facilitators of seeking or receiving help for women in abusive relationships and empower them to break free from abuse.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01MD013863) and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health & Human Development (R00HD082350). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

List of Search Terms

(‘risk’ OR ‘protective factors’ OR ‘barrier*’ OR ‘facilitator*’ OR ‘strategies’ OR ‘strategy’ OR ‘health resource*’ OR ‘intervention*’ OR ‘safety’ OR ‘psychological resilience’) AND (‘domestic violence’ OR ‘intimate partner violence’ OR ‘battered women’ OR ‘spouse abuse’ OR ‘spousal violence’ OR ‘abused women’) AND India

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

- Achchappa B, Bhandary Achchappa B, Bhandary M, Unnikrishnan B, Ramapuram JT, Kulkarni V, Rao S, Maadi D, Bhat A, & Priyadarshni S (2017). Intimate partner violence, depression, and quality of life among women living with HIV/AIDS in a coastal city of South India. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC), 16(5), 455–459. 10.1177/2325957417691137 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ahmad J, Khan N, & Mozumdar A (2019). Spousal violence against women in India: A social–ecological analysis using data from the National Family Health Survey 2015 to 2016. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(21-22), 10147–10181. 10.1177/0886260519881530 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Babu BV, & Kar SK (2010). Domestic violence in eastern India: Factors associated with victimization and perpetration. Public Health, 124(3), 136–148. 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.01.014 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Babu GR, & Babu BV (2011). Dowry deaths: A neglected public health issue in India. International Health, 3(1), 35–43. 10.1016/j.inhe.2010.12.002 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Begum S, Donta B, Nair S, & Prakasam CP (2015). Socio-demographic factors associated with domestic violence in urban slums, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 141(6), 783–788. 10.4103/0971-5916.160701 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Behr D (2017). Assessing the use of back translation: The shortcomings of back translation as a quality testing method. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory & Practice, 20(6), 573–584. 10.1080/13645579.2016.1252188 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bhandari S, & Hughes JC (2017). Lived experiences of women facing domestic violence in India. Journal of Social Work in the Global Community, 2(1), 13–27. 10.5590/jswgc.2017.02.1.02 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Biswas CS (2016). Spousal violence against working women in India. Journal of Family Violence, 32(1), 55–67. 10.1007/s10896-016-9889-9 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Chen J, & Stevens MR (2011). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_report2010-a.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- Borah PK, Kundu AS, & Mahanta J (2017). Dimension and socio-demographic correlates of domestic violence: A study from Northeast India. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(4), 496–499. 10.1007/s10597-017-0112-0 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bourey C, Stephenson R, & Hindin MJ (2013). Reproduction, functional autonomy and changing experiences of intimate partner violence within marriage in rural India. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 39(4), 215–226. 10.1363/3921513 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brislin RW (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. 10.1177/135910457000100301 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Campbell JC (2002). Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet, 359(9314), 1331–1336. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Campbell JC, Webster D, Koziol-McLain J, Block C, Campbell D, Curry MA, … & Sharps P (2003). Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: Results from a multisite case control study. American Journal of Public Health, 93(7), 1089–1097. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2008). Adverse health conditions and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence—United States, 2005. MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 57, 113–117. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5705a1.htm [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (n.d.). The social-ecological model: A framework for prevention. Accessed from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html

- Chakraborty H, Patted S, Gan A, Islam F, & Revankar A (2016). Determinants of intimate partner violence among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in India. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(3), 515–530. 10.1177/0886260514555867 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Charmaz K (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. SAGE Publications. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chernikov VV, & Goncharenko OK (2021). The problems of violence against women in international law. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University Law, 3, 803–819. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chibber KS, Krupp K, Padian N, & Madhivanan P (2012). Examining the determinants of sexual violence among young, married women in Southern India. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(12), 2465–2483. 10.1177/0886260511433512 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Christianson M, Teiler Å, & Eriksson C (2021). “A woman’s honor tumbles down on all of us in the family, but a man’s honor is only his”: Young women’s experiences of patriarchal chastity norms. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 16(1), 1862480. 10.1080/17482631.2020.1862480 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software (n.d.). Covidence [Computer software]. Veritas Health Innovation. Available at www.covidence.org . [ Google Scholar ]

- Dalal K (2011). Does economic empowerment protect women from intimate partner violence? Journal of Injury & Violence Research, 3(1), 35–44. 10.5249/jivr.v3i1.76 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dalal K, & Lindqvist K (2012). A National study of the prevalence and correlates of domestic violence among women in India. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 24(2), 265–277. 10.1177/1010539510384499 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Daruwalla N, Kanougiya S, Gupta A, Gram L, & Osrin D (2020). Prevalence of domestic violence against women in informal settlements in Mumbai, India: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open, 10(12), e042444. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042444 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Das S, Bapat U, Shah More N, Alcock G, Joshi W, Pantvaidya S, & Osrin D (2013). Intimate partner violence against women during and after pregnancy: A cross-sectional study in Mumbai slums. BMC Public Health, 13(1). 10.1186/1471-2458-13-817 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Das S, Mishra A, Patnaik KK, & Mohanty SN (2018). A cross sectional study of female married victims of domestic violence in a tertiary care hospital. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology, 12(1), 31. 10.5958/0973-9130.2018.00007.5 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Das T, & Basu Roy DT (2020). More than individual factors; is there any contextual effect of unemployment, poverty and literacy on the domestic spousal violence against women? A multilevel analysis on Indian context. SSM - Population Health, 12, 100691. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100691 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dasgupta A (2015). Understanding intimate partner violence and associated challenges to family planning among married women in Maharashtra, India. UC San Diego. ProQuest ID: Dasgupta_ucsd_0033D_15239. Merritt ID: ark:/13030/m53b93sq. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0jr396wk [ Google Scholar ]

- Dasgupta S (2019). Attitudes about wife-beating and incidence of domestic violence in India: An instrumental variables analysis. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40(4), 647–657. 10.1007/s10834-019-09630-6 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Decker MR, Nair S, Saggurti N, Sabri B, Jethva M, Raj A, Donta B, & Silverman JG (2013). Violence-related coping, help-seeking and health care–based intervention preferences among perinatal women in Mumbai, India. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(9), 1924–1947. 10.1177/0886260512469105 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Donta B, Nair S, Begum S, & Prakasam CP (2016). Association of domestic violence from husband and women empowerment in slum community, Mumbai. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(12), 2227–2239. 10.1177/0886260515573574 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dutta N, Rishi M, Roy S, & Umashankar V (2016). Risk factors for domestic violence – an empirical analysis for Indian states. The Journal of Developing Areas 50(3), 241–259. doi: 10.1353/jda.2016.0099. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gaikwad V, & Rao DH (2014). A cross-sectional study of domestic violence perpetrated by intimate partner against married women in the reproductive age group in an urban slum area in Mumbai. Indian Journal of Public Health Research & Development, 5(1), 49–54. 10.5958/j.0976-5506.5.1.013 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gangoli G, & Rew MJ (2011). Mothers-in-law against daughters-in-law: domestic violence and legal discourses around mothers-in-law against daughters-in-laws in India. Women’s Studies International Forum, 34(5), 420–429. 10.1016/j.wsif.2011.06.006 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- George J, Nair D, Premkumar NR, Saravanan N, Chinnakali P, & Roy G (2016). The prevalence of domestic violence and its associated factors among married women in a rural area of Puducherry, South India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 5(3), 672–676. 10.4103/2249-4863.197309 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goel R (2005). Sita’s Trousseau: Restorative justice, domestic violence, and South Asian culture. Violence Against Women, 11(5), 639–665. 10.1177/1077801205274522 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gupta RK, Kumari R, Singh P, & Langer B (2019). Domestic violence: A community based cross sectional study among rural married females in North West India. JK Science-Journal of Medical Education and Research, 21(1), 35–41. https://www.jkscience.org/archives/volume211/8-Original%20Article.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- Hackett M (2011). Domestic violence against women: Statistical analysis of crimes across India. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 42(2), 267–288. 10.3138/jcfs.42.2.267 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hartmann M, Datta S, Browne EN, Appiah P, Banay R, Caetano V, Floreak R, Spring H, Sreevasthsa A, Thomas S, Selvam S, & Srinivasan K (2020). A combined behavioral economics and cognitive behavioral therapy intervention to reduce alcohol use and intimate partner violence among couples in Bengaluru, India: Results of a pilot study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(23-24). 10.1177/0886260519898431 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hayes BE (2013). Women’s resistance strategies in abusive relationships. SAGE Open, 3(3), 215824401350115. 10.1177/2158244013501154 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hayes BE, & Franklin CA (2016). Community effects on women’s help-seeking behaviour for intimate partner violence in India: Gender disparity, feminist theory, and empowerment. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 41(1-2), 79–94. 10.1080/01924036.2016.1233443 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Husain H (2019). Why are South Asian immigrant women vulnerable to domestic violence? Inquiries Journal, 11 (12), 1/1. http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/1777/why-are-south-asian-immigrant-women-vulnerable-to-domestic-violence [ Google Scholar ]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. 2017. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16: India: IIPS. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR339/FR339.pdf

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. 2022. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019-21: India: IIPS. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR375/FR375.pdf

- International Finance Corporation (2018). For women in India, small loans have a big impact. Retrieved from https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/news_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/news+and+events/news/india-microfinance-loans-rural-women

- Jain S, Varshney K, Vaid NB, Guleria K, Vaid K, & Sharma N (2017). A hospital-based study of intimate partner violence during pregnancy. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics: The Official Organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 137(1), 8–13. 10.1002/ijgo.12086 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jayaram P, Shashikumar R, Das RC, Bhat PS, Srivastava K, Prakash J, Patrikar S (2014) Assessment of intimate partner violence and its correlate in an urban location. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(1), S19–S62. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jennings WG, Reingle JM, Staras SA, & Maldonado-Molina MM (2012). Substance use as a risk factor for intimate partner violence overlap: Generational differences among Hispanic young adults. International Criminal Justice Review, 22(2), 139–152. 10.1177/1057567712442943 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jewkes R, Willan S, Heise L, Washington L, Shai N, Kerr-Wilson A, Gibbs A, Stern E, & Christofides N (2021). Elements of the design and implementation of interventions to prevent violence against women and girls associated with success: Reflections from the what works to prevent violence against women and girls. Global programme. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 12129. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jeyaseelan L, Kumar S, Neelakantan N, Peedicayil A, Pillai R, & Duvvury N (2007). Physical spousal violence against women in India: some risk factors. Journal of Biosocial Science, 39(5), 657–670. 10.1017/S0021932007001836 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kalokhe A, Del Rio C, Dunkle K, Stephenson R, Metheny N, Paranjape A, & Sahay S (2017). Domestic violence against women in India: A systematic review of a decade of quantitative studies. Global Public Health, 12(4), 498–513. 10.1080/17441692.2015.1119293 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kalokhe AS, Iyer SR, Gadhe K, Katendra T, Paranjape A, del Rio C, Stephenson R, & Sahay S (2018). Correlates of domestic violence perpetration reporting among recently-married men residing in slums in Pune, India. PLOS ONE, 13(5). 10.1371/journal.pone.0197303 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kalokhe AS, Iyer SR, Kolhe AR, Dhayarkar S, Paranjape A, del Rio C, Stephenson R, & Sahay S (2018). Correlates of domestic violence experience among recently-married women residing in slums in Pune, India. PLOS ONE, 13(4). 10.1371/journal.pone.0195152 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kerr-Wilson A, Gibbs A, Fraser EM, Ramsoomar L, Parke A, Khuwaja MA, & Jewkes R (2020). What works to prevent violence against women and girls? A rigorous global review of interventions to prevent violence against women and girls. South African Medical Research Council. [ Google Scholar ]

- Khandare LP (2017). Domestic violence and empowerment: A national study of scheduled caste women in India. [Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University; ]. IUPUI ScholarWorks Repository. 10.7912/C2/1201 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kimuna SR, Djamba YK, Ciciurkaite G, & Cherukuri S (2013). Domestic Violence in India: Insights From the 2005-2006 National Family Health Survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(4), 773–807. 10.1177/0886260512455867 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kishor S, & Gupta K (2009). Gender equality and women’s empowerment in India. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), India, 2005-2006: International Institute of Population Sciences. [ Google Scholar ]

- Koenig MA, Stephenson R, Ahmed S, Jejeebhoy SJ, & Campbell J (2006). Individual and contextual determinants of domestic violence in North India. American Journal of Public Health, 96(1), 132–138. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050872 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Krishnamoorthy Y, Ganesh K, & Vijayakumar K (2020). Physical, emotional and sexual violence faced by spouses in India: evidence on determinants and help-seeking behaviour from a nationally representative survey. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 74(9), 732–740. 10.1136/jech-2019-213266 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Krishnan S, Rocca CH, Hubbard AE, Subbiah K, Edmeades J, & Padian NS (2010). Do changes in spousal employment status lead to domestic violence? Insights from a prospective study in Bangalore, India. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 70(1), 136–143. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.026 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kumar NT, Jagannatha SR, & Ananda K (2012). Dowry death: Increasing violence against women. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology, 6(1), 45–47. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kumar S, Jeyaseelan L, Suresh S, & Ahuja RC (2005). Domestic violence and its mental health correlates in Indian women. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 187, 62–67. 10.1192/bjp.187.1.62 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ler P, Sivakami M, & Monárrez-Espino J (2020). Prevalence and factors associated with intimate partner violence among young women aged 15 to 24 years in India: A social-ecological approach. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(19–20), 4083–4116. 10.1177/0886260517710484 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lewis RJ, Milletich RJ, Kelley ML, & Woody A (2012). Minority stress, substance use, and intimate partner violence among sexual minority women. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(3), 247–256. 10.1016/j.avb.2012.02.004 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Madhivanan P, Krupp K, & Reingold A (2014). Correlates of intimate partner physical violence among young reproductive age women in Mysore, India. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 26(2), 169–181. 10.1177/1010539511426474 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mahapatra N & Rai A (2019). Every cloud has a silver lining but… “pathways to seeking formal-help and South-Asian immigrant women survivors of intimate partner violence.” Health Care for Women International, 40(11), 1170–1196. 10.1080/07399332.2019.1641502 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mahapatro M, Gupta RN, Gupta V, & Kundu AS (2011). Domestic violence during pregnancy in India. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(15), 2973–2990. 10.1177/0886260510390948 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mahapatro M, Gupta R, & Gupta V (2012). The risk factor of domestic violence in India. Indian Journal of Community Medicine: Official Publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine, 37(3), 153–157. 10.4103/0970-0218.99912 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mahapatro M, Gupta RN, & Gupta VK (2014). Control and support models of help-seeking behavior in women experiencing domestic violence in India. Violence and Victims, 29(3), 464–475. 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-12-00045 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Manohar PS, & Kannappan R (2010). Domestic violence and suicidal risk in the wives of alcoholics and non-alcoholics. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 36(2), 334–338. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mathew SS, Goud RB, & Pradeep J (2019). Intimate partner violence among ever-married women treated for depression at a rural health center in Bengaluru urban district. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 44(5), 70. 10.4103/ijcm.ijcm_72_19 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mehta KG, Baxi R, Patel S, Chavda P, & Mazumdar V (2019). Stigma, discrimination, and domestic violence experienced by women living with HIV: A cross-sectional study from Western India. Indian Journal of Community Medicine: Official Publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine, 44(4), 373–377. 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_136_19 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moher D, Shamseet L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, & PRISMA-P Group (2015), Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4 (1), 1–9. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mukherjee R, & Joshi RK (2021). Controlling behavior and intimate partner violence: A cross-sectional study in an urban area of Delhi, India. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(19-20), NP10831–NP10842. 10.1177/0886260519876720 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murugan V, Khoo Y-M, & Termos M (2020). Intimate partner violence against women in India: Is empowerment a protective factor? Global Social Welfare, 8(3), 199–211. 10.1007/s40609-020-00186-0 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nadda A, Malik JS, Rohilla R, Chahal S, Chayal V, & Arora V (2018). Study of domestic violence among currently married females of Haryana, India. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 40(6), 534–539. 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_62_18 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- National Crime Victims Bureau (2019). Crime in India 2019. Accessed from https://ncrb.gov.in/sites/default/files/CII%202019%20Volume%201.pdf

- Nigam S (2017). Is domestic violence a lesser crime? countering the backlash against Section 498A, IPC. Occasional Paper No. 61: Centre for Women Development Studies. Accessed from 10.2139/ssrn.2876041 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hrobjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S …Moher D (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 29 (372), Article n71. https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n71 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Panchanadeswaran S, & Koverola C (2005). The voices of battered women in India. Violence Against Women, 11(6), 736–758. 10.1177/1077801205276088 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Patrikar S, Basannar D, Bhatti V, Chatterjee K, & Mahen A (2017). Association between intimate partner violence & HIV/AIDS: Exploring the pathways in Indian context. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 145(6), 815–823. 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1782_14 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Patrikar S, Verma A, Bhatti V, & Shatabdi S (2012). Measuring domestic violence in human immunodeficiency virus-positive women. Medical Journal, Armed Forces India, 68(2), 136–141. 10.1016/S0377-1237(12)60020-3 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Paul S (2016). Women’s labour force participation and domestic violence: Evidence from India. Journal of South Asian Development, 11(2), 224–250. 10.1177/0973174116649148 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Purkayastha B (2000). Liminal lives: South Asian youth and domestic violence. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 9(3), 201–219. 10.1023/A:1009408018107 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ragavan M, & Iyengar K (2020). Violence perpetrated by mothers-in-law in Northern India: Perceived frequency, acceptability, and options for survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(17-18), 3308–3330. 10.1177/0886260517708759 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rai A (2020). Indirect experiences with domestic violence and help-giving among South Asian immigrants in the United States. Journal of Community Psychology, 1–20. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22492 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]