Eating Disorders Research Paper

This sample eating disorders research paper features: 4600 words (approx. 15 pages), an outline, and a bibliography with 8 sources. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

I. Overview of Eating Disorder Terms

II. Continuum of Health Related to Eating Disorders

III. Diagnostic Criteria

A. anorexia nervosa, b. bulimia nervosa, c. eating disorders not otherwise specified.

IV. Epidemiology

V. Psychological and Social Impairment

VI. Medical Complications

Vii. detection and assessment, viii. treatment, a. psychotherapy, b. medication, c. nutritional counseling, d. hospitalization.

IX. Prevention

I. Overview of Eating Disorder Terms

The word “nervosa” indicates that each of these conditions is a “nervous disorder.” Psychological difficulties are likely to be involved in the development of these disorders, and also are likely to be exacerbated by the eating-disordered behavior. “Anorexia” means “lack of appetite.” The hallmark feature of anorexia nervosa (AN) is failure to maintain a minimally normal body weight. The meaning of the term “bulimia” is “ox hunger,” or “hungry as an ox.” Bulimia nervosa (BN) is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating (i.e., eating large amounts of food accompanied by a sense of loss of control) and compensatory behaviors (e.g., purging, fasting, or excessive exercise). Overlap between the symptoms of these disorders occurs in some individuals. Furthermore, individuals may engage in disturbed eating behaviors and/or indicate intense body image disparagement, but not meet full criteria for anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. Detailed information about diagnostic criteria are provided later in this research paper. It is important to note that eating-related behaviors may be best conceptualized as existing along a continuum ranging from “healthy” to “unhealthy” eating-related behaviors and body image.

II. Continuum of Health Related to Eating Disorders

The pursuit of and preoccupation with beauty represent a central feature of the female sex-role stereotype. Therefore, it is possible that attractiveness, and specifically body image, have a greater influence on self-concept for women than for men. Although standards of beauty have varied widely across time and cultures, the mass media have contributed to the development of a more uniform standard of beauty.

Unfortunately, the current images of women that are portrayed in the media often represent unrealistic weights and shapes for most women. In a classic study, Garner and colleagues demonstrated a consistent decrease in body weights and measurements of two (albeit arguable) standards of beauty (e.g., Miss America pageant winners, and Playboy centerfolds) over two decades (1950s to 1970s). Fashion models are now 23 % thinner than average women, compared to 8% thinner than average woman three decades ago. Indeed, models who depict the in-vogue “waif” look are likely to have a body weight consistent with criteria for anorexia nervosa.

Given the preponderance of images of thinness as the ideal for beauty that are depicted in the media, it is not surprising that many females would perceive their bodies as inadequate. Because women naturally have more body fat than men, even those who are of normal body weight may judge themselves as overweight. In a recent national survey, over 40% of females reported having a negative body image. Although almost one half of young girls reported wanting to lose weight in one survey, only 4% actually were found to be overweight. Women are far more likely to rate their ideal figure to be significantly thinner than actual size than are men.

Therefore, perceptions that one is overweight may be potentially more distressing for women and may lead to attempts to control body weight and shape through methods such as dieting. Female college students report dieting at much higher rates than their male counterparts. In a recent large-scale national survey data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, containing a sample of over 60,000 adults, 38% of female and 24% of male adults reported to be trying to lose weight, and 44% of females versus 15 % of males in high school sample of over 11,000 students reported to be trying to lose weight.

The high prevalence rates of negative body image attitudes and dietary behaviors found among females has been referred to as “normative discontent.” Therefore, although not necessarily “healthy,” it may in fact be “normal” for women in Western cultures to hold disparaging views toward their bodies and to engage in activities aimed at modifying their weight and shape. However, body image disparagement and dieting behaviors may pose as risk factors for the development of an eating disorder. Initial degree of body image dissatisfaction has been found to predict increased eating disturbance in longitudinal studies of adolescent girls and to predict eating disordered behavior in adults. Similarly, the interaction between body image and other risk factors (e.g., pressure for thinness) increased probability of reporting eating disturbance in female athletes. In a study of adult ballet students, body dissatisfaction and dietary restriction were found to predict eating-disordered symptoms.

Therefore, individuals who derive self-esteem primarily or exclusively based on the perception of body image may be at increased risk for development of an eating disorder. It has been argued that individuals who develop eating disorders unquestionably accept and internalize societal messages about thinness as the ideal for female attractiveness. Excessive dietary restraint, often used as a means to modify body weight and shape in an attempt to more closely correspond to a thin ideal of beauty, has been posited to increase the potential for development of binge eating. Secondary symptoms of semi-starvation resulting from prolonged dietary restriction or fasting, such as increases in preoccupation with food, urges to binge eat, and depressed mood, may lead to further exacerbation of body image disparagement and disturbed eating. Although body image concerns and dieting practices are commonplace for many women, when body image disparagement and eating disturbances become extreme and begin to interfere with functioning or to compromise health, an eating disorder may be diagnosed.

Although the symptoms of the various eating disorder syndromes overlap considerably and often are characterized as along a continuum, classification of specific eating disorders is based on criteria as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV).

The primary distinguishing feature of anorexia nervosa (AN) is the refusal to maintain a minimally normal body weight (i.e., at least 85% of expected body weight considering age and height). Despite their excessively low-weight status, individuals with AN exhibit intense fear of gaining weight. Such individuals experience their body weight or shape in a distorted manner (e.g., size distortion) and often indicate intense distress regarding body image. Body weight or shape unduly influences self-evaluation, often being the primary determinant of self-esteem. Absence of three or more consecutive menstrual cycles (i.e., amenorrhea) is also required to make a diagnosis of AN. Perhaps the feature that presents the greatest challenge in accurately assessing and effectively treating this disorder is the adamant denial of the seriousness of maintaining an excessively low body weight. Individuals with anorexia nervosa may also engage in recurrent binge eating and purging (i.e., self-induced vomiting, abuse of laxatives, or diuretics), which is classified as the binge eating/purging subtype of AN. Absence of recurrent binge eating and purging characterizes the restricting type of AN.

Within the past two decades bulimia nervosa (BN) only has been recognized as a distinct clinical disorder. The primary feature of BN is recurrent binge eating (i.e., eating large amounts of food in a short time period accompanied by a sense of loss of control) followed by methods of inappropriate compensation. Compensatory methods include purging (i.e., self-induced vomiting, or abuse of laxatives, or diuretics), fasting, or excessive exercise. Symptom frequency for a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa entails binge eating and compensatory behavior(s) occurring on average at least twice a week for a 3-month period. Perception of body shape and weight unduly influencing self-evaluation also is required for the diagnosis of BN. A diagnosis of BN is not given to individuals who receive a diagnosis of AN, because that diagnosis takes precedence. Subclassification of BN is based on type of recurrent compensatory methods, referred to as purging and nonpurging types.

A large number of individuals engage in disturbed eating behaviors, but do not meet strict diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, in which case a diagnosis of eating disorder not otherwise specified (ED-NOS) may be appropriate. Examples of symptom constellations that might meet the criteria for ED-NOS include bulimic behavior occuring less frequently than two times per week or purging in the absence of binge eating behavior. Another example of ED-NOS, binge eating disorder (BED), which is characterized by recurrent binge eating in the absence of compensatory behaviors, has been listed in the appendix of DSM-IV as a diagnosis warranting further research.

IV. Epidemiology of Eating Disorders

Although increasing prevalence combined with increased recognition of eating disorder problems for women has contributed to the perception that eating disorders have become an “epidemic,” this is not supported by epidemiological research. However, the high prevalence of eating disorders is well documented, with women representing the majority of those afflicted. Although these disorders are most commonly seen in women, approximately 5% to 10% of individuals who develop anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa are men. Research on AN and BN indicate that these disorders are most often found among Caucasian adolescent and young adult females in industrialized countries espousing the ideology of Western culture. The most recent figures indicate that from .10% to 1.0% of young females have AN. Prevalence rates are higher for BN, ranging from 1% to 3% of young women when using stringent diagnostic criteria.

Increased rates of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa have been associated with certain professions (e.g., fashion models, ballet dancers) that emphasize thinness. Elevated rates of eating disorders have also been found among individuals involved in competitive athletics, particularly those in which maintenance of a low body weight is competitively advantageous (e.g., gymnastics, running, wrestling). It is possible that participation in such activities poses as a risk factor in the development of an eating disorder. Alternatively, some individuals with established eating disorders (or body image disparagement) may be drawn to such activities, in order to use compulsive exercise as a socially condoned form of dietary compensation in efforts to maintain or achieve a low body weight.

- Psychological and Social Impairment

Body image disturbance is a central feature of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Body size overestimation among individuals with AN and BN has been empirically documented. Among individuals with AN and BN, marked fluctuations of body image disparagement frequently occur, which may precipitate and/or result from intensified eating disordered behavior.

Increased psychological distress often is found among individuals with an eating disorder. Relatively high rates of comorbid psychopathology (especially affective disorders) have been reported for samples of individuals with anorexia nervosa. In addition, problems with past or present substance abuse are not uncommon among eating disordered samples. Individuals with eating disorders also display a pattern of cognitive abnormalities, such as a dichotomous thinking style. Low self-esteem and difficulties in interpersonal relationships are often reported by individuals seeking treatment for eating disorders.

The extent to which these psychological and social difficulties may be involved in the development of eating disorders remains unclear and could be clarified by prospective, longitudinal studies. However, it is important to note that many of these symptoms are ameliorated with treatment that results in reduction or cessation of eating disordered behaviors.

Several thorough reviews are available providing detailed accounts of adverse medical sequale of eating disorders. Although prevalence rates for anorexia nervosa (AN) are relatively low, the medical consequences can be grave. Mortality rates for AN at long-term follow-up range from 6% to 20% and up to one-fourth of anorectic individuals develop severe, chronic disabilities resulting from the disorder. The results of prolonged malnutrition found in AN include certain visibly recognizable symptoms, including obvious weight loss, dry hair and skin, alopecia (i.e., hair loss), and excessive lanugo hair (e.g., fine, downy body hair). Cold intolerance, sleep disturbances, headaches, and fatigue are common among individuals with AN. Prolonged protein depletion resulting from chronic malnutrition results in additional symptoms, detectable through laboratory examinations. Abdominal pain and bloating, and constipation are often reported by individuals with AN, which may be due to delayed gastric emptying. Constipation also may result from laxative abuse and starvation. Among the most serious consequences of AN are osteoporosis, growth stunting, and cardiac complications.

Although mortality rates for bulimia nervosa are low, fatalities have been documented as a result of gastric rupture after binge eating, esophageal perforations (i.e., Boerhooves syndrome), and cardiomyopathy due to chronic ingestion of Ipecac. Fluid loss due to recurrent purging can result in dehydration and electrolyte imbalance, potentially leading to cardiovascular disturbances. Recurrent vomiting may result in esophageal erosion. Constipation and abdominal bloating and pain may result from binge eating.

Several factors contribute to the secretive nature of eating disorders, including denial of the seriousness of symptoms, embarrassment regarding the symptoms, and/or fear of the consequences of relinquishing the disturbed behaviors (i.e., potential weight gain or increased anxiety). Consequently, eating disorders often go unnoticed and can be challenging to assess, although warning signs are often present. Secretive eating, refusal to eat in public, and frequent dieting may be indicative that an individual is struggling with some form of an eating disorder; these symptoms are usually found in individuals with either anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. Behavioral indications of purging behavior include spending excessive amounts of time in bathrooms or frequently going to a bathroom immediately following eating. Excessive or compulsive physical activity may also indicate the use of exercising as a form of dietary compensation. The use of stringent diets or fasting for extended periods of time may signal the presence of an eating disorder. Substantial changes in body weight, including weight fluctuations, or continued weight gain or loss may also be indicative of an eating disorder.

Emaciation is usually the primary physical indication of anorexia nervosa. Measurements of body weight obviously aids in determining if an individual is below 85% of expected weight; however, individuals with AN may drink excessive amounts of fluid or wear concealed weights in an attempt to manipulate assessment of body weight. Overactivity (e.g., continuous body movement or pacing) is often observed among individuals with AN. As described above, some of the additional detectable signs of AN include dry skin and hair, lanugo, and alopecia. Ammenorhea may also indicate the possibility of AN, although the use of oral contraceptives may complicate the detection of this symptom.

Although frequent weight fluctuations may signal the presence of bulimia nervosa (BN), many individuals with BN are of normal weight and appear relatively healthy. Although BN is usually less easily detected than anorexia nervosa, certain signs may aid in its detection. One indication of recurrent self-induced vomiting, sometimes referred to as a “Russell’s sign,” is the development of callouses or scarring on the back of the hand resulting from abrasion during self-induced vomiting. This symptom may not be present in those individuals who primarily use alternative forms of purging (i.e., laxative, diuretic, or enema abuse), who have nonpurging BN, or who after prolonged vomiting have come to do so reflexively. Self-induced vomiting may also contribute to hypertrophy of the salivary glands, creating a swollen appearance of the neck and face (i.e., “puffy cheeks”). Although this symptom may be fairly pronounced in some women, it is not detectable in the majority of individuals with BN. Additional signs include the presence of small skin hemorrhages (i.e., facial petechiae) or conjunctival hemorrhages that may result from forceful vomiting. Dental enamel erosion, most pronounced on the inside surface of the upper teeth, is another indication of purging that may produce protrusion of dental fillings or discoloration (i.e., darkening) of the teeth. This symptom, which is easily detected during dental examinations, may be overlooked during routine physical examinations unless specifically assessed. Edema may be present for those who abuse laxatives or diuretics. Individuals with BN often present with complaints of “bloating,” constipation, or lethargy. Laboratory tests may be used to detect electrolyte imbalance, although such abnormalities are detected in only approximately 40% of individuals with BN.

Psychotherapy is commonly used in the treatment of eating disorders. One form of psychotherapeutic intervention, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been the most extensively studied. Based on the work of Beck for the treatment of depression, CBT is a time-limited, present-focused, solution-oriented form of therapy. This approach is based on “collaborative empiricism” in which the client and therapist actively work together using an experimental approach to resolve a specified problem. As applied to eating disorders, the primary focus is on modifying disordered eating behaviors and distorted cognitions about food, weight, and shape. A combination of behavioral techniques, cognitive interventions, and emphasis on relapse prevention are integrated in this approach. The efficacy of CBT has been demonstrated in several studies of BN. Favorable reduction rates of binge eating (ranging from 77% to 93%) and purging (74% to 94 %) have been reported for five of the most recent, large studies. Methods used in behavior therapy (BT) also are commonly integrated in CBT treatment for individuals with eating disorders. Studies comparing BT with CBT have generally demonstrated that the addition of cognitive interventions to behavioral methods are associated with similar or greater clinical gains.

The efficacy of an alternative type of psychotherapy, Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT), recently has been demonstrated in treating individuals with BN, as well as BED. IPT is time-limited, present-focused, and solution-oriented. IPT differs from CBT in that the emphasis of treatment is on modification of interpersonal interactions, rather than eating disordered behavior or cognitions.

Another therapeutic approach that has been investigated is supportive-expressive therapy, a short-term, nondirective, dynamically informed modality that conceptualizes core conflicts in terms of interpersonal issues. Although supportive-expressive therapy was found to be effective in reducing binge eating in this study, CBT was found to be associated with greater improvements in many aspects of eating disturbance and psychopathology, and a higher rate of remission in bulimic symptoms.

Alternative psychotherapeutic approaches to treating individuals with eating disorders recently have been well articulated, although no controlled outcome studies have yet to be conducted. The relative efficacy of psychodynamic therapy is unclear given the absence of empirical data. However, this approach may be beneficial for clients who have not derived benefit from less intensive interventions, such as CBT. Feminist therapists have convincingly argued for the importance of considering sociocultural and political issues in designing interventions for individuals with eating disorders. The potential efficacy of psychotherapeutic interventions incorporating feminist perspectives warrant future empirical investigation.

Although favorable results have been reported using psychotherapy, particularly CBT and IPT, several limitations of this body of research warrant discussion. Despite the substantial rates of symptom reduction and remission reported in these studies, it is important to note that approximately one-third to one-half of participants remained symptomatic at the end of treatment. Furthermore, strict inclusion criteria utilized in research studies such as these limit the generalizability of the findings, which may not be representative of the majority of individuals seeking treatment for bulimia nervosa. Data are not available regarding the relative efficacy of individual versus group administration of CBT or IPT. Additional research comparing the relative efficacy of alternative psychotherapeutic approaches is warranted. However, this body of literature provides support for the efficacy of using solution-focused psychotherapeutic interventions such as CBT and IPT in treating individuals with BN.

Despite the fact that anorexia nervosa (AN) has received attention from clinical researchers for several decades, little empirical data are available regarding efficacy of psychotherapy for this disorder. To a large extent, the paucity of AN treatment research is attributable to the logistical difficulties involved in implementing controlled studies with this population. Only four outpatient psychotherapy studies of AN have been reported to date, with some suggestions of effectiveness. The potential benefits of using behavioral modification programs (which overlap to a certain extent with CBT interventions) during inpatient hospitalization has received support in several studies. Although limited empirical data are available regarding the relative efficacy of individual versus family therapy in treating individuals with eating disorders, some therapists have convincingly articulated the potential benefits of using family approaches in working with eating disordered individuals. Some empirical support exists for using family therapy for younger individuals with AN. Additional research is needed to investigate various psychotherapeutic interventions for treating individuals with AN, and relapse prevention strategies, given the substantial rate of relapse in those who initially respond to treatment.

Antidepressant medications have been found to effectively reduce binge eating and purging symptoms in several bulimia nervosa studies. Four controlled trials involving outpatient samples have demonstrated the superiority of serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) in comparison to placebo in reducing bulimic symptoms, although one impatient trial failed to support added benefit for the drug. These medications generally have been found to be well-tolerated. Therefore, fluoxetine hydrochloride (Prozac) administered at daily doses of 60 mg (higher than the recommended dose of 20 mg used to treat individuals with major depressive disorder) is considered by some the first choice for pharmacotherapy for BN. The use of tricyclic antidepressants or monoamine oxidase inhibitors also is supported by research. Although the side effects of these classes of medications may be more problematic for many individuals than the SRIs, they may be beneficial treatment strategies for those individuals who do not respond to the use of SRIs. In addition, some clinicians prefer the second generation tricyclics, such as despiramine, as the initial intervention owing to the lower cost of the medication.

Despite the relative efficacy of antidepressant medications compared to placebo in reducing bulimic symptoms, it is important to note that rates of bulimic symptom remission at end of treatment range from 4 % to 20% in most studies. These rates of symptom remission are lower than those reported in psychotherapy outcome studies. Augmenting psychotherapy with pharmacotherapy may seem indicated in some cases, although results from research on this are mixed. Three studies have reported no benefit to adding antidepressant treatment regimen to psychotherapy on outcome in eating variables, and the results are equivocal in one study. There is some suggestion that certain other symptoms, such as those of depression, may benefit from the combination of interventions.

Little empirical data are available from investigations of the benefits of pharmacotherapy in promoting weight restoration in individuals with anorexia nervosa. Approximately a dozen controlled trials have been conducted on variety of medications, yielding often ambiguous results. Benefits have been demonstrated for the use of amitriptyline in one study and for cyproheptadine in two studies. However, the majority of placebo-controlled studies, investigiating the efficacy of these and other medications (e.g., antipsychotics, clonidine, cisapride, lithium, and tetrahydrocannabinol) have not demonstrated efficacy in promoting weight restoration.

Nutritional counseling is often regarded as a necessary therapeutic component for treatment of individuals with eating disorders. Healthy meal planning is the cornerstone of this approach, which involves providing objective nutritional information about the types and amounts of food necessary to achieve or maintain adequate nutrition and healthy weight. Behavioral strategies are also employed to increase the likelihood of successfully adhering to nutritional recommendations. Nutritional counseling is essential for the treatment of anorexia nervosa, which requires an increase in caloric intake to promote gradual weight restoration at a rate of I to 3 pounds per week. Nutritional counseling is also useful for treating BN to help stabilize the dietary chaos that often promotes binge eating.

At times sufficient medical danger exists (e.g., dehydration, severe electrolyte imbalance, gastrointestinal bleeding, severe emaciation, suicidal ideation) to require inpatient hospitalization. Goals of hospitalization include interruption of weight loss (usually if less than 70 to 75% of ideal body weight), progress toward restoration of healthy body weight, cessation of binge eating or vomiting, treatment of medical complications, and treatment of comorbid conditions (e.g., depression or substance abuse). Hospitalization also may be indicated if clinical benefits are not obtained from adequate outpatient therapy. This may be required for severely underweight individuals who, evidence starvation-induced impaired cognitive functioning.

Day treatment, or partial hospitalization, may be recommended following inpatient discharge or as an alternative to hospitalization. This type of treatment allows patients to receive therapy during the day without requiring an overnight stay. This type of treatment is more economical than inpatient hospitalization and is less socially disruptive. Additional benefits of this type of treatment include allowing the patient to pursue work or education while obtaining intensive treatment, and providing a structured atmosphere during meal times.

IX. Prevention of Eating Disorders

Given the prevalence of these disorders and the seriousness of the psychological and medical sequelae, the prevention of eating disorders is an important area that requires increased attention. Such efforts often involve providing psychoeducational information in school-based settings aimed at reducing unhealthy dieting behavior and enhancing body acceptance, often involving critical analysis of messages conveyed through mass media. A number of eating disorder studies have been conducted to investigate the effectiveness of primary prevention programs. However, an unfortunately consistent finding across such studies is that although knowledge about eating disorders often increases, behavioral changes (i.e., reductions in unhealthy dietary practices) have not been detected among participants. Failure to observe the desired behavioral outcomes of primary prevention programs may be attributable, in part, to a variety of methodological challenges, including the validity of self-report assessments and the relatively low baseline frequency of eating disordered behaviors (e.g., self-induced vomiting) among the general adolescent population. However, it is also possible that, in order to have a significant impact, prevention efforts may need to be delivered to individuals at a younger age (i.e., elementary school). Increased understanding of the complex etiology of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa may be required in order to develop more comprehensive and effective prevention strategies. In addition, relatively little attention has been devoted to investigating the effectiveness of secondary prevention of eating disorders. As such, effective strategies to assist in identifying individuals who are experiencing initial symptoms of an eating disorder and facilitating appropriate treatment remain an important area to be developed.

Stringent diagnostic criteria show that the prevalence for any single eating disorder is rather low. However, combining prevalence rates across various types of disorders reveals that up to 5 to 10% of women may be afflicted with a diagnosable eating disorder (i.e., AN, BN, or ED-NOS). Serious medical, psychological, and social consequences are associated with these disorders.

The treatment of individuals with eating disorders often requires a multifaceted approach (e.g., psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, nutritional counseling, medical management) involving members of several professional disciplines (e.g., dieticians, psychologists, psychiatrists, internists) and various settings (e.g., inpatient, outpatient, day treatment, residential).

Literature on the treatment of these disorders indicates that substantial progress has been made in the last few decades. However, a sizable subgroup of individuals with either anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa do not adequately respond to established therapies, or do respond but subsequently relapse. Much additional work is needed in predicting treatment response, matching individuals to treatments, and developing relapse prevention strategies. Furthermore, effective primary and secondary prevention strategies remain to be established.

Bibliography:

- Brownell, K. D., & Fairburn, C. G. (Eds.). (1995). Eating disorders and obesity. New York: Guilford Press.

- Fairburn, C. G. & Wilson, G. T. (Eds.). (1993). Binge eating: Nature, assessment and treatment. New York: Guilford Press.

- Fallon, P., Katzman, M. A., & Wolley, S. C. (Eds.). (1994).Feminist perspectives in eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press.

- Garner, D. M. & Garfinkel, P. E. (Eds.). (1997). Handbook of treatment for eating disorders. (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- Mitchell, J. E. (Ed.). (1990). Bulimia nervosa. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Smolak, L., Levine, M. P., & Striegel-Moore, R. (Eds.). (1996). The developmental psychopathology of eating disorders: implications for research, prevention and treatment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Striegel-Moore, R.H., Silberstein, L.R., & Rodin, J. (1986). Toward an understanding of risk factors for bulimia. American Psychologist, 41,246-263.

- Thompson, J.K. (Ed.). (1996). Body image, eating disorders, and obesity. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

- High School

- You don't have any recent items yet.

- You don't have any courses yet.

- You don't have any books yet.

- You don't have any Studylists yet.

- Information

PSY470 RS T3 Outline Template

Abnormal psychology (psy-470), grand canyon university, recommended for you, students also viewed.

- PSY 470 RS T1 Subject Selection

- Case Study abnormal psy

- Bipolar disorder newsletter vreyes

- Abnormal Psychology Final Research Paper - Schizophrenia

- Models of Abnormality Matrix Assignment

- Outline Template

Related documents

- Subject Selection

- Character Analysis Paper

- Abnormal Psychology Research Paper Rough Draft - Schizophrenia

- Benchmark - Anxiety and Phobias Paper

- PSY-470 Topic 1 DQ 1

- PSY-470 Topic 1 DQ 2

Preview text

Psy-470 abnormal psychology research paper outline.

Topic/Proposed Title: Eating Disorders

Introduction: We all know that food is necessary for us to survive, along with water, but what would happen to the body if someone were to eat too much or too little? Eating disorders are classified as mental health disorders where people will have irregular or troubled eating patterns. People who struggle with eating disorders can have different problems like becoming obsessed with their dietary decisions, weight, or looks. Even though there are about 6 types of eating disorders, this paper will only discuss anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder (Petre, 2022).

Purpose & Thesis Statement: This paper will have general explanations of what the three types of eating disorders are, what types of diseases or medical conditions can be involved (comorbidity) and will discuss as to why they are included in one or more models of abnormality (DSM-5), or etiology.

1 st Main Point: That Serves to Support Your Thesis:

Eating disorders are illnesses that can develop into unhealthful eating patterns. They usually begin with an obsession with food, weight, or physical appearance. When eating disorders are severe, they can have a substantial negative impact on health and, if ignored, can even be fatal (Petre, 2022). o This article has explanations of each eating disorder and talks about the symptoms and just how badly it can impact one’s life. It also gives treatment options and tips on how to help others who suffer with eating disorders.

There are different ways in which someone would eat with one of these disorders. Some will avoid food as in only eating small amounts of certain foods (National Institute of Mental Health, 2021). Other people would lose control over their eating habits and consume large amounts. Some cases this would follow up on the person to have excessive vomiting, fasting, etc. while others would not do those things.

o This article explains what each disorder could cause someone to out of their control. There is treatment options and lifelines in the article. © 2023. Grand Canyon University. All Rights Reserved.

2 nd Main Point: That Serves to Support Your Thesis: what types of diseases or medical conditions can be involved (comorbidity)

Eating disorders can affect one’s physical health, but when certain disorders have high rates of comorbidity with other types of disorder, it can greatly affect one’s mental health as well (Bridley & Daffin, 2021). o The article has different examples to show which of the disorders have similar disorders and which ones could be worse due to symptoms or the amount of food consumed.

People with an eating disorder have a higher risk of developing psychiatric, psychological, and medical conditions (National Eating Disorders Collaboration. (n.). o The article explains in separate sections for psychiatric and medical comorbidities. Different types of disorders involved and why they are common within eating disorders.

3 rd Main Point that Serves to Support Your Thesis: why they are included in one or more models of abnormality (DSM-5)

Eating disorders are multidimensional disorders, meaning that there are different factors that lead to the eating disorder (Bridley & Daffin, 2022). o The article explains the factors as it includes biological, cognitive, sociocultural, and personality traits as some causes for eating disorders.

Researchers are finding out more about how eating disorders can be caused by interactions of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors (National Institute of Mental Health, 2022). o There are researchers that are still looking into understanding eating disorders and why they have different ways it can be developed.

Conclusion: Write out your plan for how you will conclude. You do not need to submit your actual conclusion since you have not yet completed the rough draft.

© 2023. Grand Canyon University. All Rights Reserved.

- Multiple Choice

Course : Abnormal Psychology (PSY-470)

University : grand canyon university.

- More from: Abnormal Psychology PSY-470 Grand Canyon University 711 Documents Go to course

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Experiences of eating disorders from the perspectives of patients, family members and health care professionals: a meta-review of qualitative evidence syntheses

Sanna aila gustafsson, karin stenström, hanna olofsson, agneta pettersson, karin wilbe ramsay.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2021 Aug 25; Accepted 2021 Nov 7; Collection date 2021.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Eating disorders are serious conditions that cause major suffering for patients and their families. Better knowledge about perceptions of eating disorders and their treatment, and which factors that facilitate or hinder recovery, is desired in order to develop the clinical work. We aimed to explore and synthesise experiences of eating disorders from the perspectives of those suffering from an eating disorder, their family members and health care professionals through an overarching meta-review of systematic reviews in the field.

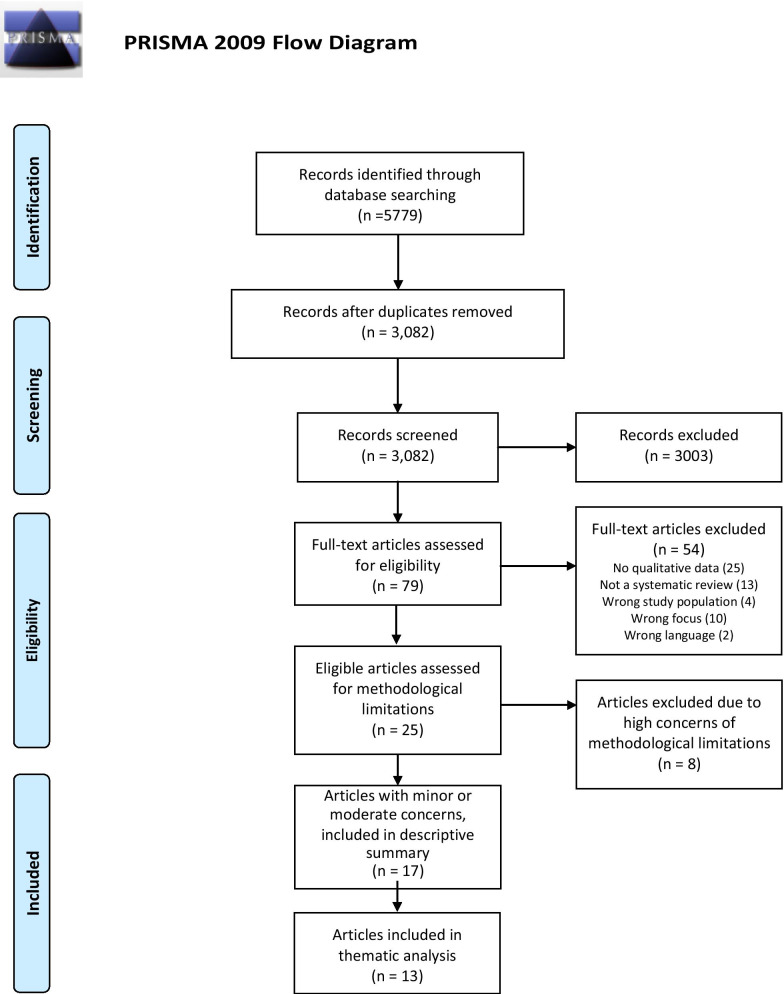

A systematic literature search was conducted in the databases PubMed, PsycInfo, Scopus, and CINAHL. Inclusion criteria were systematic reviews of qualitative research on experiences, perceptions, needs, or desires related to eating disorders from the perspective of patients, family members or health care professionals. Systematic reviews that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were assessed for relevance and methodological limitations by at least two researchers independently. The key findings were analysed and synthesised into themes.

We identified 17 systematic reviews that met our inclusion criteria. Of these, 13 reviews reported on the patients’ perspective, five on the family members’ perspective, and three on the health care professionals’ perspective. The study population in the reviews was predominantly girls and young women with anorexia nervosa, whilst systematic reviews focusing on other eating disorders were scarce. The findings regarding each of the three perspectives resulted in themes that could be synthesised into three overarching themes: 1) being in control or being controlled, 2) balancing physical recovery and psychological needs, and 3) trusting relationships.

Conclusions

There were several similarities between the views of patients, family members and health care professionals, especially regarding the significance of building trustful therapeutic alliances that also included family members. However, the informants sometimes differed in their views, particularly on the use of the biomedical model, which was seen as helpful by health care professionals, while patients and family members felt that it failed to address their psychological distress. Acknowledging these differences is important for the understanding of anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders, and may help clinicians to broaden treatment approaches to meet the expectations of patients and family members.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40337-021-00507-4.

Keywords: Eating disorders, Anorexia nervosa, Evidence synthesis, Qualitative research, Meta-review, Meta-synthesis

Plain English summary

The current paper brings together existing knowledge on experiences of eating disorders. We were interested in the views of patients, family members and health care professionals. A literature search identified 17 systematic reviews which addressed these questions. The identified research focused mainly on girls and young women with anorexia nervosa, while research on other eating disorders was limited. Overall, this review suggests that it is important to acknowledge that patients, family members and health care professionals may have different experiences and views regarding treatment of eating disorders, and that it is important to consider all these views in the development of the care of eating disorders.

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) are serious psychiatric conditions that often have both psychological and physical consequences and significant societal costs [ 1 , 2 ]. An ED can lead to social problems and reduced quality of life for both the victim and his or her family [ 3 ]. The debut is often during adolescence, although in recent years there has been an increase in new-onset EDs in adults [ 4 , 5 ]. The lifetime prevalence of EDs in Western countries has been estimated to 1.89% [ 6 ]. Girls and women are more often affected than men. Previously, it has been estimated that about 90 percent of those affected are women, but new studies estimate that the proportion of men could be around 20 percent [ 7 ].

ED often require multi-disciplinary treatment [ 8 ]. Most patients are treated in outpatient care, but in more serious cases there may be both day care and inpatient medical or psychiatric care. There are also several inpatient units that specialise in treatments for patients with an ED [ 9 ].

The recommended psychological treatment for adult patients is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which has is strongest empirical support for patients with bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge eating disorder (BED), but is also increasingly recommended for patients with anorexia nervosa (AN) [ 8 – 10 ]. Family-based treatment is the treatment method that is primarily recommended for adolescents. The method is mainly adapted for patients with AN or other restrictive conditions but is also considered to have a good effect for adolescents with BN [ 8 , 9 ].

It is estimated that about half of all people with AN are fully recovered after treatment. At ten-year follow-up, about 73 percent are in remission. The short-term effect of treatment is slightly better for other types of EDs, but there is a significant risk of relapse. In ten years' time, there are marginally more people recovering from BN compared with AN [ 11 ].

Health care professionals often describe that patients with an ED are a challenging group of patients and that it can be difficult to establish a good treatment alliance [ 12 ]. Patients, on the other hand, often describe strong feelings of ambivalence and resistance, which of course complicates treatment, and leads to conflicts with family and friends [ 13 , 14 ].

An improved common understanding of EDs from the perspective of those affected, their family members and caregivers can contribute to better care and treatment for those struggling with EDs and help reduce the strain on their relationships.

Against this background, the aim of the present study was to investigate experiences of living with an ED and factors that facilitate or hinder recovery from the perspectives of patients, their family members and health care professionals.

The current meta-review is based on an assessment conducted at The Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services [ 15 ]. The literature overview was undertaken in accordance with the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) statement [ 16 ] following an a priori protocol that was registered locally at the agency.

Search strategy

A systematic literature search covering literature published from January 1, 1990 to September 26, 2018, was conducted in the electronic databases PubMed (NLM), PsycInfo (EBSCO), Scopus (Elsevier), and CINAHL (EBSCO). A complementary, multi-database, search was also conducted. The databases Academic Search Elite, ERIC, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, and SocINDEX, were searched simultaneously through the EBSCO platform. The detailed search strategy is provided in Additional File 1 .

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were specified in advance. We only included systematic reviews of qualitative research that were published in peer reviewed journals in English, Swedish, Norwegian, or Danish within the time period 1990 to 2018. To be included, a systematic review should cover experiences, perceptions, needs or desires related to EDs from at least one of the following perspectives: persons with eating disorders, family members or health care professionals. All types of EDs according to the DSM-5 classification were considered relevant except for pica, rumination disorder and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. There were no restrictions regarding the age of the informants. The targeted reviews were required to cover original studies of qualitative research or of mixed methodology. Systematic reviews using both broad and narrow search strategies were accepted. Grey literature, such as theses, book chapters, and conference abstracts, were excluded.

Study selection

The titles and abstracts retrieved from the literature search were examined independently by two of the authors using the web-based screening tool Rayyan[ 17 ]. If at least one author found an abstract potentially relevant, the article was ordered in full text and assessed for eligibility by at least two authors independently. Systematic reviews that fulfilled the eligibility criteria were forwarded to quality assessment.

Assessment of methodological quality, data extraction and analysis

Systematic reviews that fulfilled the eligibility criteria were assessed for quality by at least two authors independently, using a tool developed at the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (Additional File 2 ). The tool was developed specifically to assess methodological limitations of qualitative evidence synthesis and consists of 13 questions that were adapted from the ENTREQ recommendations [ 16 ]. The summarised risk of methodological limitations in the systematic reviews was judged as being of minor, moderate or high concern. Any disagreement between assessors was resolved by discussion. Systematic reviews with high concerns of methodological limitations were excluded from the subsequent process.

Relevant data were extracted from eligible systematic reviews with minor to moderate methodological concerns and summarised in tables.

The findings of selected systematic reviews (reviews with a narrow focus were not included in the synthesis) were analysed using the method of thematic analysis described by Braun and Clarke [ 18 ]. For each group of informants (patients, family members and health care professionals), findings were coded through an inductive analysis. Next, the coded findings were structured by subject within each group of informants and synthesised into themes. The themes were reviewed, similarities and disparities between the three groups of informants were analysed and the themes were assembled into main themes. Data extraction and synthesis was carried out by the first author (SAG) who has clinical experience treating EDs as well as expertise in qualitative research. Data extraction and synthesis of themes were carefully read and partly checked against the original data by three other authors who have experience of qualitative (AP) or quantitative research (KS, KWR) and expertise in conducting systematic reviews. The differing backgrounds of the authors presumably reduced the risk of introducing bias in the analysis and presentation of data. Throughout the synthesis, the authors discussed the findings with each other and reflected over how their background and position may have affected the analysis and whether there were other ways to interpret the results.

The literature search identified 3,082 citations, after removal of duplicates (Fig. 1 ). From the screening of title and abstracts, 79 reviews were retrieved and assessed for eligibility in full text, and 25 of these fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Eight reviews were considered to have high concerns of methodological limitations and were excluded from the subsequent process. The remaining 17 reviews were included and described (Table 1 ). Of these, four reviews had a scope that differed substantially from the other reviews (two reviews focused on pregnant women with AN [ 19 , 20 ], one review focused on gender issues [ 21 ] and one focused on treatment seeking [ 22 ], therefore, they were only included in the descriptive summary but not in the thematic analysis. Thus, the thematic analysis included data from 13 systematic reviews.

PRISMA flow chart

Included systematic reviews

Descriptive summary of the systematic reviews

The 17 systematic reviews with minor or moderate concerns of methodological limitations were published between 2009 and 2018 and were based on a total of 255 unique qualitative primary studies. An assessment of study overlap revealed that few of the primary studies were included in more than one review (see Additional File 3 ). The majority of the included reviews were based on studies using qualitative methods only, but three reviews also included studies that used mixed methods [ 22 – 24 ]. Most of the original studies had used interviews as the primary source of data, but some studies were based on focus group discussions, survey responses, or observations of behaviour.

Most reviews carried out synthesis using meta-ethnography [ 19 , 25 – 33 ]. Other synthesis methods were thematic analysis [ 22 , 23 ], qualitative meta-analysis [ 34 ], and various forms of integrative synthesis methods [ 20 , 21 , 24 , 35 ]. Few of the included reviews stated that they had followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement[ 22 , 34 ] or the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the synthesis of Qualitative research (ENTREQ) system[ 31 , 32 ]. In most reviews, however, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) had been used to assess the quality of the primary studies [ 19 – 21 , 25 – 29 , 31 – 34 ].

A total of 13 systematic reviews described the patients’ perspectives [ 19 – 23 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 30 – 34 ], five concerned the family members’ perspectives [ 24 , 26 , 29 , 31 , 32 ], and three focused on the health care professionals’ perspectives [ 31 , 32 , 35 ]. Most reviews included both men and women with EDs, and only three reviews focused exclusively on women [ 19 , 20 , 33 ]. Most reviews did not specify age under the inclusion criteria, but no review included studies on young children. Five reviews focused on adolescents with EDs but they also included young adults [ 23 , 24 , 30 – 32 ]. Nine reviews focused exclusively on AN [ 23 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 30 – 33 , 35 ], while the remaining reviews included all EDs, or did not specify diagnosis in the inclusion criteria. One of the reviews that covered health care professionals’ perspectives included interviews exclusively with nurses [ 35 ] whereas the other two comprised nurses, therapists, and treatments teams [ 31 , 32 ]. The informants in the reviews that included family members were predominantly parents, but siblings and partners were also included in some of the reviews [ 24 , 26 , 29 , 31 , 32 ].

Thematic analysis of the systematic reviews

In each of the three perspectives we identified three themes that described experiences of the disease, the care provided and the recovery process. When the three perspectives were analysed together, we identified three overarching themes that were shared among all three perspectives (see Table 2 ). The themes are described in the table below and organized by perspective. Illustrative quotes for each theme are provided in Table 3 .

Overview of subthemes and overarching themes from the 13 systematic reviews that were included in the thematic analysis

Themes and quotations from the systematic reviews

The perspective of individuals with ED

Nine systematic reviews describing the patients’ perspectives were included in the thematic analysis [ 23 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 30 – 34 ]. This perspective comprised three themes; a lonely struggle for control (covered by three studies [ 28 , 31 , 33 ]), a wish to be seen as a whole person (covered by four studies [ 23 , 27 , 30 , 32 ]), and finding the keys to recovery (covered by five studies [ 23 , 25 , 27 , 33 , 34 ]).

A lonely struggle for control

Life with an ED was described as a lonely and isolated existence, with health problems and difficulties in relationships [ 28 , 31 , 33 ]. Low self-esteem, a negative body image and perfectionist demands on themselves were seen as underlying factors that led to a difficult adolescence, and uncertainty about who they were.

For those with AN, the disorder was seen as an integral part of their personality and the person they were, which also made them afraid to get well since they feared that it could mean losing their identity [ 28 , 31 , 33 ].

Living with AN was described as a struggle to be in control while simultaneously feeling controlled by the disease. The positive experience of control contributed to feeling special and having power (for example over their treatment) and the ED was described as a "coping strategy" that helped them deal with difficult emotions and events. For the majority of patients, the other side of the coin was a difficult experience of losing, or giving up control, for example when entering treatment, or feeling trapped in their illness and symptoms. The subjects described how their whole life revolved around a compulsive focus on calorie counting and compensatory behaviours and how this resulted in a lonely and isolated existence [ 28 , 31 , 33 ].

A wish to be seen as a whole person

When seeking treatment, patients had often felt ill-treated and misunderstood, especially in general care [ 23 , 27 , 30 , 32 ], and therefore, they stressed the necessity of access to specialised ED care. The patients often felt that the health care focused too much on physical recovery and on normalization of eating and weight. This was perceived as unempathetic and gave patients the impression that the therapists did not understand the patient's real problems. Although patients could see that normalization of weight and eating was an important and necessary part of treatment, they felt that focusing too heavily on physical recovery led to feel that they were being reduced to their disease [ 23 , 27 , 30 , 32 ].

Instead, they emphasised that there must be room for conversation about thoughts and feelings and that the care they received should take their wider life situation into account. It was also felt necessary that the therapistwas able to adapt and change his/her approach during the course of the treatment. Initially, the patients might need a therapist that was proactive and took control. At a later stage when the patient was able to take responsibility, treatment should empower and encourage the patient to take control of his/her own life.

Family-based treatment was common for young patients. These patients often felt considerable guilt towards parents and siblings, and they described that a positive aspect of family treatment was that it could help the whole family to feel better, bring them together, and improve their communication. However, patients also described feeling unable to talk about everything that was important to them in family treatment. This risked the treatment becoming superficial and focused on concrete behavioural changes instead of dealing with the underlying causes of the condition. The young patients therefore felt that it was important that family treatment was combined with individual therapy. Individual therapy was seen as an important forum for motivating, engaging and giving patients hope. Patients perceived that it was important to address issues such as relationships both within and outside the family, and to be seen as a unique individual, rather than simply as a person with AN [ 23 , 27 , 30 , 32 ].

Finding the keys to recovery

In the studies that focused on AN, patients consistently described recovery as something “greater” than the mere absence of an ED diagnosis. An experience of being healthy did not arise automatically once weight and eating were normalized. Patients described recovery as a process of getting to know themselves and daring to admit that the false sense of control that the ED had given them had actually come to control them. Recovery meant being able to stick to healthy behaviors even when it felt difficult [ 23 , 25 , 27 , 33 ].

Four factors were described as central to recovery; to regain control and power over one's own life, changing the anorexic identity and finding and accepting oneself behind the disease; getting in touch with one's true feelings and acknowledging the consequences of the disease for oneself, thereby challenging the anorexic thoughts.

In the systematic review that described recovery more generally for people with an ED, it was found that patients perceived the term "healthy" as including feeling well emotionally, socially and psychologically. It included having strategies for dealing with difficulties that arise in life and feeling a sense of belonging or feeling that life is meaningful.

Recovery was described as a process that took place in stages and sometimes with setbacks. Recovery was facilitated by supportive relationships, such as with family and friends. Trusting relationships with family and friends could have a double impact, both by motivating the ill person to seek treatment [ 25 ] and by providing support during the recovery process. Trusting relationships with health care professionals were also considered important both for the motivations to seek and stay in treatment [ 25 ] and for the recovery process itself [ 34 ].

The health care perspective

Three systematic reviews included the experiences of health care staff [ 31 , 32 , 35 ], and all three focused mainly on AN. Two of them [ 31 , 32 ] examined similarities and differences in perceptions of AN and its treatment among staff, patients and relatives. The third overview [ 35 ] explored the knowledge, attitudes and perceived challenges of health care professionals.

The health care perspective also revealed three themes: a tug of war over control, the necessity of physical recovery, and being let into someone’s world.

A tug of war over control

The health care staff saw control as a central aspect of AN and they felt that besides the need to control their own body, patients also felt a need to control their family through the ED [ 32 ]. The staff perceived that the need for control became a force outside the patient's active choice and that the ED ended up controlling the patient instead. The staff therefore felt that they had to "take over" control from the young person through clear structure and rules regarding treatment [ 32 , 35 ]. This was considered to create security for the young person, and to give them the opportunity to allow themselves to let go of control. However, in one study, nurses also stressed the importance of knowledge and understanding of the disease, and described how a lack of knowledge could lead to staff using control strategies in a repressive and punishing way that could create resentment [ 35 ].

The necessity of physical recovery

The health care staff used a biomedical model to understand AN [ 31 , 32 ]. AN was seen as a disease to be treated. This meant that staff emphasised weight rehabilitation and changes in other observable ED symptoms as important parts of treatment. The staff expressed that they were lacking knowledge about ED symptoms and diagnosis, and that they had insufficient skills for dealing with patients' problems [ 35 ]. This led them to feel frustrated and insecure in meeting the patients. Increased knowledge was seen as essentialfor improving staff attitudes towards people with EDs.

The medical view of the ED was perceived as helpful by staff because it was considered to reduce the patient's and their relatives' feelings of guilt. Health care professionals found it helpful to see the disease as a phenomenon separate from the individual. The staff used this "externalisation" to distinguish between disease and patient as a treatment strategy [ 31 , 32 ]. It was considered to reduce the patient's feelings of guilt and increase the patient's motivation.

Even under this theme, a review by Salzman et al. [ 35 ] also emphasised the other side of the coin, meaning.e., that although weight rehabilitation was important, a single-minded focus on physical issues could hamper the relationship with the patient.

Being let in to someone’s world

A good alliance between patient and therapist was considered essential [ 31 , 32 , 35 ]. Honesty, understanding, respect and a non-judgmental and empathetic attitude were important for building an alliance. The staff expressed that patients with EDs were a difficult and demanding patient group with whom it was challenging to form an alliance and who often expressed suspicion and distrust of their caregivers. Staff became frustrated with patients' ambivalence or reluctance to engage in treatment and sometimes perceived patients as manipulative.

One of the systematic reviews examined the health care professionals' experiences of meeting relatives, in this case parents of people with an ED [ 32 ]. The staff emphasised the importance of building a positive alliance with the parents and engaging them in the treatment. This was considered a necessary condition for effective treatment of young patients with AN.

The perspective of family members

Five systematic reviews covered the perspective of family members [ 24 , 26 , 29 , 31 , 32 ]. All of them focused mainly or exclusively on AN. Like the other two perspectives, the perspective of family members also revealed three themes; the balancing act between control and trust, a call for a more holistic approach to treatment, and a wish for a working alliance with the whole family.

The balancing act between control and trust

The family members felt that the whole family was negatively affected by the afflicted person’s illness [ 24 , 26 , 29 , 31 , 32 ]. The family members described the ED as an active choice which the sufferer, at least at some point during the course of the disease, could have refrained from [ 29 ]. The family members felt that controlling eating and weight had, for the ill person, become a way of coping in a life where other things felt uncontrollable, but that the ED had instead taken control of their loved one and changed her personality and behaviour [ 26 , 29 , 31 ]. Family patterns and old roles changed [ 24 , 26 , 29 , 31 , 32 ] and the family members described communication as characterised by conflict, mistrust and uncertainty. It could be perceived that the person with the ED had regressed, which led parents to become more controlling. The opposite sometimes happened with siblings, who would take on a more mature role, becoming a "mediator" in the family and taking greater responsibility.

Family members described a difficult balancing act between adapting to the ill person by, for example changing the family's eating habits and activities, andbeing more demanding. The family members tried to find a balance between controlling and making demands on the ill person, and at the same time reinforcing and encouraging positive steps and showing trust in her/him. To some extent, they felt that it was important to adapt the family's social activities and meals by, for instance, not having certain foods in the house. However, this sometimes resulted in them "walking on eggshells" and accepting behaviours that were counterproductive in the long term. Siblings were often critical of the parents' strategies and thought that they adapted too much.

A common strategy to cope with this balancing act was to distinguish the disease from the individual and to see certain behaviours as “the disease that speaking”. This helped the family members to maintain a supportive attitude, even when they felt that the person with the ED was misbehaving [ 24 , 26 , 29 , 31 , 32 ].

A call for a more holistic approach to treatment

It was stressful to see the person with an ED suffering, and the family members felt anxiety, frustration and guilt. Their everyday lives were affected, both socially and professionally. Many informants reported that the family became more isolated and that they stopped associating with others. Several of the systematic reviews reported that family membersno longer had time for hobbies and that working life was affected [ 24 , 29 ]. Against this background, family members stressed the importance of easier and faster access to specialised care with experienced and committed staff who could give the whole family including siblings information and support, and put them in touch with support networks outside the family to connect with others who were in the same situation. [ 24 , 26 , 29 , 31 , 32 ].

Parents often felt that the health care model was too biomedical and focused too much on physical symptoms such as starvation. They perceived that the unique person behind each patient was not seen [ 24 , 29 , 32 ]. Although the biomedical explanatory model could help to relieve parents' feelings of guilt, it also conveyed a negative image of the patient's chances of recovery [ 29 ]. The family members emphasised that it was important that the therapist saw the patient as an individual and that the therapy did not focus too narrowly on correcting the ED symptoms, but also incorporated other things that were important to the patient [ 24 , 29 , 32 ].

A wish for a working alliance with the whole family

The parents often blamed themselves for their child’s ED [ 24 , 26 , 29 , 31 , 32 ] and they thought a lot about it’s possible origins in the family and the child’s upbringing. The siblings felt severely affected by the situation, something that was also described by their parents [ 24 , 26 , 29 , 32 ]. Siblings became anxious and often took great responsibility for both the afflicted sibling and their parents. At the same time, they often felt angry with their unwell sibling, and sometimes jealous that they were receiving more time and attention from their parents. The healthy siblings sometimes felt a conflict of loyalty and also were compelled to mediate between the afflicted sibling and the parents [ 29 ].

Family members often experienced a lack of support from the health service, especially at the beginning of the illness [ 24 , 26 , 29 , 31 , 32 ]. It was difficult to get a correct diagnosis and adequate help, and family members had to fight to get the right care for the affected person. Family members often felt excluded from care and experienced that health care staff did not support them or listen to them. This exclusion was often attributed to rules or principles that had to do with confidentiality or legislation. Family members also felt that they received conflicting advice and suggestions from the health service or that they were not taken seriously [ 29 ].

The three overarching themes

Our synthesis identified three themes in common among the views of patients, family members and health care professionals (Table 2 ). The first theme pertained to the patients’ need for control, which was seen by the family members and the health care professionals as a false control, where the affected person was in fact controlled and limited by the ED. The second theme was the balancing of physical recovery and psychological needs, where the biomedical model was viewed differently from each of the three perspectives. Health care professionals felt that, if used with the right knowledge and competence, the model gave them the support they needed to define target symptoms and goals for recovery, while patients and family members felt that the model placed too much focus on the somatic aspects of the disorder and failed to address psychological distress. The third theme was the importance of forming trusting relationships for accomplishing a well-functioning therapeutic alliance that recognises the whole individual and not just the disease, and that also involves family members.

This meta-review brings together a substantial amount of qualitative research, including data from 255 unique studies, on the experiences of EDs from the perspectives of patients, family members and health care professionals. Three themes emerged from the synthesis; the patients’ need for control, balancing physical recovery and psychological needs, and the importance of trusting relationships in the treatment of the disorders. Although all three main themes were identified in the views of all three groups of informants, there were some differences in their expression that may be important to acknowledge.

Implications for health care systems

The ED causes a great deal of suffering for both the affected person and the family members, and both parties emphasise the importance of getting the right treatment. From our synthesis, however, there appears to be a divergence between ED patients and their family members on the one hand, and the health care staff on the other, regarding how the ED should be understood and treated. Health care professionals often represent a biomedical explanatory model, while ED patients and their family members feel that this model is not sufficient. These different approaches are not necessarily conflicting, but can potentially complicate the alliance building and pull the treatment in different directions, where the professionals place more emphasis on symptom reduction and weight rehabilitation, while the patients and their family members want a more holistic approach to treatment and recovery. This conflict, and suggestions for how to avoid it, was also emphasised in one of the studies involving health care staff [ 35 ]. The main suggestion from patients, family members and health care staff on how to achieve this holistic approach, while still attending to the physical needs of the patient, was to increase the knowledge. The importance of having access to staff who are knowledgeable in terms of both understanding the disease and attending to the patient’s physical needs, and understanding their psychological struggles, and are able to meet the patient in a respectful way, cannot be overemphasised.

In today's health care, and among policy makers, there is an increasing focus on using manual-based treatments and on measuring the outcomes of treatment. Great emphasis is placed on questions about which treatment method has the best scientific support, and how to make sure that therapists actually deliver the method according to the manual [ 36 ]. These are of course important questions that need to be addressed. However, it is important to acknowledge that these aspects seem to be entirely absent from patients’ and families’ descriptions of what is lacking or what is important in treatment. On the contrary, persons with an ED's desire treatment that is more flexible and individualised, with greater focus on their unique, individual situation. None of the systematic reviews in this study mentioned that patients or family had called for any specific method of treatment, instead they called for a more holistic and individually-adapted care. Since a significant proportion of ED patients discontinue treatment prematurely [ 37 ], and a common reason for this is lack of motivation [ 38 ], it is important that health care providers increase their knowledgeabout how patients and family members perceive the care provided, and what would motivate patients to stay in treatment.

Treatment manuals are a set of principles designed to be applicable to each individual patient. When delivered flexibly and skilfully there is no reason why individualised care should be in conflict with the use of treatment manuals [ 39 ]. However, many clinicians regard treatment manuals as constraining their practice and limiting the individualisation of interventions [ 39 ]. Against this background, and the findings of this study in terms of patients and relatives calling for a more holistic and individualised treatment, it seems that ED treatment faces a great challenge in integrating theory, research, clinical knowledge and the important perspectives of patients and their families in order to improve and adapt ED treatment. For this to be successful, it has been suggested that we need to expand the scope of treatment research and stimulate diversity within ED treatment and research [ 40 ].

Limitations and strengths

One limitation of this meta-review, which is a common problem in qualitative research syntheses, is the considerable variability in research aims, data collection approaches and methods of synthesis that were present in reviews as well as in the primary studies. Another problem that is difficult to avoid in qualitative syntheses is the possibility that the authors’ underlying assumptions may have introduced bias through selection of the experiences and views that are presented in the studies. The risk of overestimating the findings through data redundancy should also be considered, but is probably not a major problem in this meta-review since most of the included reviews had a unique focus and the study overlap was limited (Additional File 3 ).

In our quality assessment, we found that most systematic reviews that fulfilled our inclusion criteria were of high or moderate methodological quality. However, relatively few of the included reviews stated that they had followed the PRISMA or ENTREQ statement, and the compliance with these guidelines can indeed be enhanced – for example, by reporting how many reviewers were involved in the screening of studies and whether they worked independently (PRISMA checklist item 8)[ 41 ]. Other shortcomings in the included reviews were inadequate reporting of when in the progression of the disorder the data was collected, and inadequate information on the study authors’ competence in the field. In most reviews, however, a tool for critical appraisal of the original studies had been used, such as the CASP tool.

The major strengths of this meta-review are its broad scope – including three different perspectives of key informants – and the rigorous methodology of the literature screening, which involves systematic assessment of methodological limitations in the included reviews. The tool that we used for assessment of qualitative systematic reviews was developed in parallel to this meta-review and incorporates elements from the PRISMA guidelines [ 41 ] and the ENTREQ recommendations [ 16 ]. We believe that this tool can also be useful for other authors of qualitative meta-reviews. Another strength of the current study is the adequacy of the data. Most of the findings in our meta-review were based on at least three different systematic reviews and seven to 32 primary studies.

The study population and research needs

The included reviews focused mainly on anorexia nervosa (AN) or on EDs in general, without specifying a particular diagnosis. None of the identified reviews exclusively evaluated individuals with bulimia nervosa (BN) or binge eating disorder (BED), which was somewhat surprising. The possibility to generalise our findings to other EDs than AN is thus limited. To our knowledge, no systematic review that specifically focuses on experiences of BN or BED have been published after our literature search was performed. Considering the high prevalence of BN and BED that have been reported [ 6 ], there is a need to highlight experiences of these disorders in future qualitative systematic reviews.