An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Nurses' knowledge and confidence in recognizing and managing patients with sepsis: A multi‐site cross‐sectional study

Wei ling chua, chin shim teh, muhammad amin bin ahmad basri, shi ting ong, noel qiao qi phang, ee ling goh.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence , Wei Ling Chua, Alice Lee Centre for Nursing Studies, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore City, Singapore. Email: [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Revised 2022 Jul 26; Received 2022 Apr 14; Accepted 2022 Aug 20; Issue date 2023 Feb.

This is an open access article under the terms of the http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ License, which permits use and distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non‐commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.

(1) To examine registered nurses' knowledge and confidence in recognizing and managing to patients with sepsis and (2) identify nurse and workplace factors that influence their knowledge on sepsis.

A multi‐site, cross‐sectional survey.

An online survey was developed and content validated. Data was collected from registered nurses working in the inpatient wards and emergency departments of three hospitals of a single healthcare cluster in Singapore during August 2021. Statistical analyses of closed‐ended responses and content analysis of open‐ended responses were undertaken.

A total of 709 nurses completed the survey. Nurses possessed moderate levels of knowledge about sepsis (mean score = 10.56/15; SD = 2.01) and confidence in recognizing and responding to patients with sepsis (mean score = 18.46/25; SD = 2.79). However, only 369 (52.0%) could correctly define sepsis. Nurses' job grade, nursing education level and clinical work area were significant predictors of nurses' sepsis knowledge. Specifically, nurses with higher job grade, higher nursing education level or those working in acute care areas (i.e. emergency department, high dependency units or intensive care units) were more likely to obtain higher total sepsis knowledge scores. A weak positive correlation was observed between sepsis knowledge test scores and self‐confidence ( r = .184). Open comments revealed that participants desired for more sepsis education and training opportunities and the implementation of sepsis screening tool and sepsis care protocol.

A stronger foundation in sepsis education and training programs and the implementation of sepsis screening tools and care bundles are needed to enhance nurses' knowledge and confidence in recognizing and managing patients with sepsis.

The findings of this study are beneficial to administrators, educators and researchers in designing interventions to support nurses in their role in recognizing and responding to sepsis.

Keywords: acute care, confidence, education, knowledge, management, nursing, recognition, registered nurse, sepsis, survey

1. INTRODUCTION

Sepsis, a clinical syndrome of dysregulated host response to infection leading to life‐threatening organ dysfunction, is a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality (Singer et al., 2016 ). It is a major challenge for healthcare systems worldwide because it leads to significant consumption of healthcare resources (Rudd et al., 2018 ). Sepsis imposes a large economic burden; for example, the annual cost on hospital care for patients with sepsis in the United States is estimated at more than US$24 billion (Paoli et al., 2018 ). In addition, each year, there are approximately 14 million sepsis survivors who have an increased risk of recurrent infections and hospital readmissions, and this comes with grave physical and financial consequences (Prescott & Angus, 2018 ). At present, the estimated burden of sepsis is reported to be 48.9 million cases worldwide and 11 million of sepsis‐related deaths, suggesting a 20% mortality rate for sepsis (Rudd et al., 2020 ). In Singapore alone—a high income country with 5.6 million population, close to 5000 deaths were attributed to sepsis from pneumonia and urinary tract infection in 2019 (Singapore Ministry of Health, 2020 ). This was an approximate 13% increment from those reported in 2012 (Singapore Ministry of Health, 2020 ). Incidence of sepsis will continue to rise with interplay of multiple factors including aging population with more predisposing comorbidities, use of immunosuppressive therapy, and emergence of multi‐drug antimicrobial resistance (Rhee & Klompas, 2020 ). The considerable impact of sepsis highlights the importance of raising awareness to promote early recognition and treatment. Nurses play a pivotal role in the early recognition and management of sepsis because they are uniquely positioned to make the first crucial assessment in detecting sepsis and implementing timely intervention to prevent clinical deterioration.

1.1. Background

Sepsis is recognized as a global health priority by the World Health Organization (WHO) which has adopted a resolution on improving the prevention, diagnosis and management of sepsis (Reinhart et al., 2017 ). As a time‐critical medical emergency that is treatable and preventable, early recognition of sepsis with expeditious interventions is paramount in reducing the progression of sepsis and improving patient outcomes (See, 2022 ). Delays in sepsis recognition and treatment could lead to septic shock, a condition that can result in multiorgan system failure and ultimately death (Singer et al., 2016 ). The International Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC), led by the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, has provided evidence‐based recommendations for clinicians to improve sepsis care (Dellinger et al., 2004 ).

Increased adherence to sepsis guideline bundles has led to better outcomes with reduced need for ICU admission, shorter hospital length of stay and lower mortality (Levy et al., 2015 ; Milano et al., 2018 ). Compelling evidence has shown that delay in executing each intervention and completing the bundle was associated with higher mortality (Pruinelli et al., 2018 ; Seymour et al., 2017 ). Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that management of sepsis can only commence after appropriate assessment and diagnosis have been made. Yet, identifying patients, especially in the earlier stages of sepsis continuum, poses a significant challenge due to its highly variable and non‐specific clinical manifestations (Vincent, 2016 ). As such, the need to recognize sepsis accurately and quickly has led to development of sepsis screening tools which is an important element of sepsis performance improvement programs (Evans et al., 2021 ).

In the healthcare system, nurses play a pivotal role in identifying patients with sepsis and promptly escalate care for commencing diagnostic work and initiating treatment (See, 2022 ). In the emergency department (ED), triage nurses are often the first point of contact for assessing patients with community‐acquired sepsis. In the ward settings, nurses are in a privileged position to identify hospital‐onset sepsis at its earliest possible time because they spend the most contact hours doing routine bedside monitoring of patients. Nurse‐led sepsis screening interventions have demonstrated positive impact on reducing mortality and improving process measures of sepsis care bundles (McDonald et al., 2018 ; Torsvik et al., 2016 ). It is therefore crucial that nurses understand the importance of their role in sepsis recognition, are trained to identify possible sepsis and have the self‐confidence to respond and intervene with appropriate actions.

Internationally, there are several papers that published on nurses' level of knowledge on sepsis (Nucera et al., 2018 ; Rahman et al., 2019 ; Stamataki et al., 2014 ; Storozuk et al., 2019 ; van den Hengel et al., 2016 ). The findings were consistent and revealed knowledge deficits on systemic inflammatory response syndrome, signs and symptoms of sepsis, and its initial management. However, these studies often asked lower order questions that relied on participants' factual recall of sepsis knowledge instead of higher order application and analytical questions that simulate real sepsis scenarios. Furthermore, it is important to note that the questions asked in a few of the earlier studies were no longer in line with the updated sepsis‐3 definitions and management guidelines (Nucera et al., 2018 ; Stamataki et al., 2014 ; van den Hengel et al., 2016 ). With improved research leading to better understanding of sepsis pathophysiology, the Sepsis Task Force published The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis‐3) was published in 2016 (Singer et al., 2016 ). Sepsis‐3 encompasses organ dysfunction resulting from the patient's response to an infection (Singer et al., 2016 ). This was significantly different from Sepsis‐2, which emphasized on the presence of two or more systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria with a concomitant infection to define sepsis. With the new definitions of sepsis, the SSC recommended the initiation of a set of sepsis care bundle upon recognition of sepsis, which includes obtaining blood cultures followed by administration of antimicrobials, measuring lactate levels, initiating at least 30 ml/kg intravenous crystalloids in sepsis‐induced hypoperfusion or septic shock and starting vasopressors to maintain mean arterial pressure ≥ 65 mmHg during or after fluid resuscitation (Evans et al., 2021 ).

In addition to sepsis knowledge, nurses' level of self‐confidence—one's beliefs about their capability and skills—has been identified as an important factor contributing to the recognition, escalation and management of paediatric sepsis (Harley, Schlapbach, et al., 2021 ). However, research on nurses' self‐confidence in recognizing and managing adult sepsis is lacking. Thus, the interest in undertaking this study arose with the intent to assess if nurses are in keeping with the sepsis‐3 definitions and guidelines using applied knowledge test and to examine their confidence levels in recognizing and managing sepsis. The findings from this study will help identify gaps in nurses' knowledge and competencies, thereby providing insights into developing future sepsis education and practice interventions to improve clinical outcomes.

2. THE STUDY

This study aimed to explore registered nurses' (RN) knowledge and confidence in recognizing and managing patients with sepsis. The specific objectives were to: (1) examine RNs' knowledge of sepsis and level of self‐confidence in recognizing and managing patients with sepsis and (2) identify nurse and workplace factors that influence their knowledge on sepsis.

2.2. Design

A multi‐site, cross‐sectional design using an anonymous online survey was conducted.

2.3. Participants and setting

This study was conducted in three hospitals of one public healthcare cluster in the western region of Singapore. Hospital A is a 326‐bed integrated general hospital that provides holistic and seamless care from acute, subacute to rehabilitative settings, catering to the needs of residents living in the oldest housing estate in Singapore and Southwest of Singapore. The hospital has a 24‐h urgent care centre (UCC) that provides immediate medical attention to walk‐in patients and patients conveyed via private ambulance with acute and urgent medical conditions. Hospital B is a 700‐bed acute hospital offering a range of comprehensive medical services, except obstetrics and gynaecology, paediatrics and transplant medicine. Hospital C is a 1200‐bed university‐affiliated tertiary referral hospital with more than 50 medical, surgical and dental specialties, offering a comprehensive range of specialist care for adults, women and children. At the point of study, none of the hospitals had a hospital sepsis protocol or care bundle in place. Except for the ED of Hospital B, the rest of the study sites and clinical areas do not have a sepsis screening tool in place. The ED of Hospital B adopts the national early warning score 2 (NEWS2), which predicts risk of clinical deterioration and in‐hospital mortality based on a patient's physiological parameters (Royal College of Physicians, 2017 ). A cut‐off point of NEWS2 ≥ 5 serves as a trigger to alert clinicians to attend to these patients immediately and initiate evaluation for possible sepsis.

In Singapore, the basic preparatory education for RNs can be attained through either a 3‐year nursing diploma programme or a 3‐year nursing bachelor's degree programme (Chua et al., 2019 ). Following the basic nursing preparatory education, RNs can choose to acquire further in‐depth speciality‐specific skills and knowledge through advanced diplomas, graduate diplomas and post‐graduation education (Woo et al., 2020 ). A convenience sample of RNs, including advanced practice nurses (APNs), involved in the clinical care of patients in inpatient wards, including intensive care units (ICUs) and high dependency units (HDUs), ED or UCC of the three hospitals was recruited for the study. RNs who were working in the paediatrics settings, operating theatres or ambulatory surgery and outpatient clinics were excluded from the study.

2.4. Data collection

Data collection was conducted over a one‐month period starting in early August 2021. Participants were recruited through a three‐step process: (1) An email invitation to the study, comprising a letter to invite all RNs to participate, an electronic recruitment poster, the survey's hyperlink and a quick response (QR) code to access the survey, was first sent to the nursing leaders overseeing nursing research activities of the three hospitals. (2) The nursing leaders disseminated the study invitation to the nursing officers (i.e. nurse managers and nurse clinicians) and APNs of their respective hospitals. (3) Subsequently, the nursing officers of inpatient settings and ED/UCC circulated the study information face‐to‐face during roll calls and virtually via announcement portals to the ground nurses. The hardcopy recruitment poster was also pinned on the wards' noticeboard. To gather a higher response rate, the email invitation to the nursing leaders was re‐sent at 2 and 4 weeks after the first email and 3 days prior to closure of data collection. Participants were compensated S$5 (≈US$3.55) as remuneration for the time and effort they have provided in participating in the research.

The online survey was collected using Qualtrics and piloted to ensure user friendliness, ease of electronic interface and effective response collection. The survey was developed by the study team and designed to evaluate RNs' knowledge about sepsis and their perceived confidence in recognizing and managing patients with sepsis. The survey instrument comprised four sections (Supplementary file 1 ). Section one, consisting of 10 items, gathered demographic and workplace data. Section two consisted of five items, which asked the participants to rate their perceived confidence in recognizing and managing patients with sepsis, on a 5‐point Likert scale. The total confidence scores ranged from 1 to 25, with higher scores indicating higher confidence in caring for patients with sepsis. Section three assessed RNs' knowledge about sepsis. It comprised 15 multiple choice questions (MCQs), of which four questions were on general knowledge of sepsis and 11 questions were scenario based MCQs. There were three short case scenarios (diabetic foot sepsis, urosepsis and catheter‐related sepsis) and the questions covered four domains: early clinical manifestations of sepsis, sepsis laboratory investigations, patient monitoring and management of sepsis. The last section has an open‐ended component to allow participants to provide free texts to comment on organizational support to improve nurses' roles in early recognition and management of patients with sepsis.

2.5. Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (Ref No.: 2020/01480). Participation in the survey occurred on a voluntary basis and the completion and submission of the online survey implied the participant's consent. No personal identifiable data was collected. Confidentiality and anonymity about the survey responses were assured for all the participants.

2.6. Data analysis

For all statistical analyses, the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 26.0 was used (IBM Corp., 2019 ). Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviations (SD), medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), proportions and percentages) were computed to summarize the participants' demographic characteristics, workplace data, sepsis knowledge scores and self‐confidence scores. Independent sample t ‐test and one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction were used to examine the differences in nurses' total sepsis knowledge and total self‐confidence scores among the various categorical demographic and workplace subgroups. To explore the factors influencing nurses' sepsis knowledge (dependent variable), the variables (years of nursing experience, job grade, clinical work area, education level, sepsis education and training in the last 1 year, and presence of sepsis screening tool) found to be statistically significant at p ≤ .1 in the univariate linear regression analyses were used as independent variables in the subsequent multiple linear regression analysis.

Pearson product–moment correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the association between sepsis knowledge and level of self‐confidence. Chi‐square test was used to compare the item‐level responses in their level of self‐confidence towards recognizing and managing patients with sepsis grouped according to the presence of sepsis screening tool and clinical work area. In all other analyses, the level of statistical significance was set at .05.

A content analysis of the open‐ended responses collected in Section four of the survey was conducted. Line‐by‐line open coding of the short free‐texts was performed. Codes with similar meanings were grouped into the same categories and related categories were clustered into themes (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004 ). Regular discussions were held among the authors to finalize the themes derived from the content analysis process.

2.7. Validity, reliability and rigour

The survey instrument was assessed for content and face validity by a panel of seven content experts, who were APNs, a nursing academic, and an intensive care specialist. Each content expert was asked to independently rate the relevance of each item using a 4‐point Likert scale (1 = not relevant to 4 = very relevant) and was also asked to provide comments. The item‐level content validity index of the confidence scale and sepsis knowledge MCQs ranged between 0.86 and 1.00, with a scale‐level content validity index of 1.00. Based on the results of the content validation assessments and comments from the content experts, minor revisions were made for the final version of the survey. The international consistency of the confidence scale estimated by Cronbach's alpha was .870.

3.1. Nurse and workplace characteristics

A total of 709 RNs (response rate: 23.1%) across the three study sites completed the questionnaire. The demographic characteristics and workplace data of the participants are presented in Table 1 . Over 80% of the participants held the job grade of staff nurse and senior staff nurse, and close to one‐third ( n = 217, 30.6%) had between 6 and 10 years of nursing experience. Almost one‐fifth ( n = 136, 18.1%) of the respondents had attained a specialization within their field of practice. Twenty‐five of the 29 participants with a master's degree had attained master's degree in nursing and were either APN or APN interns.

Demographics and workplace characteristics of participants ( n = 709)

Abbreviations: APN, advanced practice nurse; ED, emergency department; HDU, high dependency unit; ICU, intensive care unit; UCC, urgent care centre.

25 attained Master's degree in nursing.

Only ED of Hospital B has sepsis screening tool.

For workplace data, most participants worked in the general ward settings ( n = 380, 53.6%). Ninety‐six respondents (13.5%) attended sepsis education or training in the last 1 year from the time of data collection. One hundred participants indicated the presence of sepsis screening tool in their area of practice. However, only the ED of study Hospital B has implemented a sepsis screening tool. Yet, only 50 (74.6%) out of the 67 participants were aware of the presence of a sepsis screening tool, while 14 were unsure and three were oblivious to it.

3.2. Nurses' sepsis knowledge

The total sepsis knowledge score ranged from 3 to 15, with a mean score of 10.56 ± 2.01 out of a maximum score of 15. The greatest proportion of participants ( n = 135, 19.0%) answered 12 questions correctly and only 6 participants (0.8%) correctly answered all the questions in the sepsis knowledge test. Table 2 summarizes the participants' sepsis knowledge performance at item level.

Nurses' sepsis knowledge item‐level performance, based on numbers of correct answers ( n = 709)

Abbreviation: ED, emergency department; HDU, high dependency unit; ICU, intensive care unit; UCC, urgent care centre.

The correct responses for the four questions related to general knowledge of sepsis ranged between 52.0% (definition of sepsis) and 91.0% (risk factors of sepsis). Most selected “bacteria in blood” ( n = 167, 23.6%) and “infection” ( n = 140, 19.7%) as the definition of sepsis. About half responded incorrectly to the question on the cause of sepsis ( n = 378, 53.3%) and close to one‐third responded incorrectly to the question about epidemiological data of sepsis ( n = 246, 34.7%).

In the short case scenarios section, the four questions (Q9, Q10, Q13 and Q14) that addressed the treatment of sepsis were answered correctly by between 66.0% (Q13. vasopressors therapy for septic‐shock induced hypotension) and 91.1% (Q14. blood culture prior to starting intravenous antibiotics) of the participants. On the questions related to sepsis laboratory investigations, close to two‐thirds correctly identified blood culture as the most essential septic workup ( n = 456, 64.3%) and about half of the participants were able to identify serum lactate level of 4.0 mmol/L as a concern for patients with sepsis ( n = 376, 53.0%). However, of concern, only 8.3% ( n = 59) could identify high respiratory rate as an early clinical manifestation of sepsis.

As presented in Table 2 , chi‐squared tests showed that nurses working in acute care areas such as ED/UCC and ICU/HDU had greater knowledge than general ward nurses in questions related to the immediate management of sepsis and septic shock. Nurses working in the ICU/HDU were shown to fare significantly better in their assessment and evaluation of septic shock treatment (Q15) compared to nurses working in ED/UCC and general wards.

3.3. Differences in sepsis knowledge among different groups of nurses

The total sepsis knowledge scores by nurses' and workplace characteristics are presented in Table 3 . Significant differences in nurses' sepsis knowledge scores were observed between nurses of different years of nursing experience, clinical work area, nursing job grade and education level. Nurses with more than 10 years of nursing experience scored significantly higher in sepsis knowledge test than those under 6 years of nursing experience ( F = 8.63, p < .001). Total sepsis knowledge scores differed significantly by clinical work area, with nurses working in ED/UCC (mean = 11.03, SD = 1.94) reporting higher scores compared to nurses working in ICU/HDU (mean = 10.98, SD = 1.71) and general wards (mean = 10.17, SD = 2.09). Total sepsis knowledge scores were also observed to be highest among assistant nurse clinicians and nursing officers ( F = 31.29, p < .001), master's‐prepared nurses ( F = 23.89, p < .001) or APNs and APN interns ( t = −7.54, p < .001). No significant differences in total sepsis knowledge score were observed in relation to attendance in sepsis education and training in the last 1 year and the presence of sepsis screening tool subgroups.

Differences in sepsis knowledge and self‐reported confidence scores among different group of RNs ( n = 709)

One‐way ANOVA test.

Independent sample t ‐test.

Post‐hoc test with Bonferroni correction: 0–2 years versus 6–10 years ( p = .007), 0–2 years versus >10 years ( p < .001), 3–5 years versus >10 years ( p = .001).

Post‐hoc test with Bonferroni correction: 0–2 years versus 3–5 years ( p < .001), 0–2 years versus 6–10 years ( p < .001), 0–2 years versus >10 years ( p < .001), 3–5 years versus >10 years ( p = .005).

Post‐hoc test with Bonferroni correction: staff nurse versus senior staff nurse ( p < .001), staff nurse versus assistant Nurse Clinician/nursing officer ( p < .001), senior staff nurse versus assistant Nurse Clinician/nursing officer ( p = .009).

Welch ANOVA due to unequal variance assumed, post‐hoc test with Bonferroni correction: staff nurse versus senior staff nurse ( p < .001), staff nurse versus assistant Nurse Clinician/nursing officer ( p < .001).

Welch ANOVA due to unequal variance assumed, post‐hoc test with Bonferroni correction: emergency department versus general ward ( p < .001), ICU/HDU versus general ward ( p < .001).

Post‐hoc test with Bonferroni correction: Group I versus Group II ( p < .001), Group I versus Group III ( p < .001), Group II versus Group III ( p = .018).

Post‐hoc test with Bonferroni correction: Group I versus Group II ( p = .002), Group I versus Group III ( p = .001).

25 attained master's degree in nursing.

Hospital B emergency department.

3.4. Factors affecting nurses' sepsis knowledge

Univariate linear regression analyses were done to examine the relationship between RNs' characteristics and their total sepsis knowledge score. Given post hoc test with Bonferroni correction did not demonstrate any significant difference between RNs with 0–2 years and 3–5 years of nursing experience as well as between RNs with 6–10 years and more than 10 years of nursing experience, RNs were regrouped into two groups: (1) 0–5 years of nursing experience and (2) more than 5 years of nursing experience.

Years of nursing experience, nursing job grade, clinical work area and education level were identified to be sufficient for inclusion ( p ≤ .1) in the multiple linear regression analysis. Nurses' job grade ( F = 10.82, p < .001), nursing education level ( F = 7.70, p < .001) and clinical work area ( F = 9.18, p < .001) were found to be significant predictors of nurses' sepsis knowledge, which accounted for 12.6% variance ( R 2 = .126). A nursing specialization or master's level education, holding a higher job grade and working in acute care areas (i.e. ED/UCC/ICU/HDU) were predictors of higher sepsis total sepsis knowledge scores. Details of the univariate and multiple linear regression model are presented in Table 4 .

Univariate linear regression analysis and multiple linear regression examining factors affecting nurses' sepsis knowledge ( n = 709)

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; HDU, high dependency unit; ICU, intensive care unit; UCC, urgent care centre.

Included in the multiple linear regression.

Nursing diploma only, nursing diploma and degree only, or nursing degree only.

Nursing advanced/graduate/specialist diploma + a .

Nurses with master's degree, 25 out of 29 had attained master's degree in nursing and were either advanced practice nurse or advanced practice nurse intern.

3.5. Nurses' self‐reported confidence

The total self‐confidence scores in recognizing and managing patients with sepsis ranged from 5 to 25, with a mean score of 18.46 ± 2.79 out of a maximum score of 25. The greatest proportion of participants ( n = 201, 28.3%) scored 20 for total self‐confidence score. Overall, there was a weak positive correlation between nurses' sepsis knowledge and self‐perceived confidence in the recognition and management of sepsis ( r = .184, p < .001).

The differences in self‐reported confidence among different groups of nurses are presented in Table 3 . Higher total self‐confidence scores were observed among nurses with more than 10 years of nursing experience ( F = 19.04, p < .001), assistant nurse clinicians and nursing officers ( F = 23.66), master's‐prepared nurses or APNs and APN interns ( t = −4,85, p < .001). Nurses who received sepsis education and training in the last 1 year also had significantly higher total self‐confidence scores ( t = −6.08, p < .001). There were no significant differences in total self‐confidence scores among nurses based on their clinical work area as well as between the presence of sepsis screening tool subgroups.

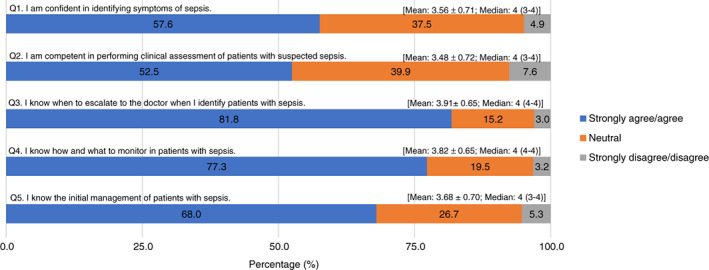

Figure 1 summarizes the participants' item‐level self‐reported confidence. Of the five items, more than three‐quarters of the nurses believed that they know when to escalate possible sepsis to the medical team and had knowledge in monitoring patients with sepsis. Conversely, slightly over half are confident in identifying and assessing patients for sepsis.

Nurses' self‐reported confidence in recognizing and managing sepsis ( n = 709).

A further analysis was done to examine if there were significant differences in the level of self‐confidence towards recognizing and managing patients with sepsis among nurses grouped according to clinical work area and presence of sepsis screening tool in their work area (i.e. nurses in ED of hospital B). At item level, no significant difference was found between nurses in ED of Hospital B (presence of sepsis screening tool) and nurses working in clinical areas without a sepsis screening tool in their confidence towards recognizing sepsis symptoms, monitoring and assessment of sepsis, escalation of sepsis to the medical team and initial management of sepsis.

3.6. Organizational support for improving sepsis care: Open‐ended results

Of the 709 participants, 591 (83.3%) provided their responses in the free text on the open‐ended question regarding organizational support for improving sepsis care. Three main themes, each supported by subthemes, were derived from the content analysis of the 591 valid entries (Supplementary file 2 ). Participants indicated the need for more regular and formal “sepsis training and education” ( n = 450) on assessing patients with sepsis, sepsis management and sepsis prevention. The suggested mode of education delivery included regular in‐service talks and seminars, e‐learning, case sharing and discussions, clinical teaching by physicians, and simulation. To aid nurses in caring for patients with sepsis, many also suggested having a hospital “sepsis workflow and protocol” ( n = 173) which included a sepsis screening tool and escalation policy, and a sepsis management bundle or algorithm. Cue cards and posters could be placed in clinical areas to facilitate adherence to sepsis workflow and protocol. Lastly, some suggestions cited were associated with “nursing empowerment” ( n = 26). Participants reported the importance of physicians listening to nurses' inputs or concerns regarding a patient's condition, having workflows that empower ward nurses to initiate initial sepsis management within their capacity and having a sepsis resource or outreach nurse to raise the profile of sepsis recognition and management.

4. DISCUSSION

This cross‐sectional study sampled RNs from three hospitals of one public healthcare cluster in Singapore and explored their knowledge and confidence in recognizing and managing adult patients with sepsis. In contrast to previous studies that tended to ask lower order factual sepsis knowledge questions, the sepsis knowledge test developed for this study focused more on higher order thinking skills, involving the application and analysis of sepsis knowledge using case scenarios questions. The findings of this study provide meaningful evidence to suggest that RNs across different areas of practice have average knowledge on sepsis care and identify gaps in nurses' sepsis knowledge. The results are consistent with previous studies despite the difficulties in making direct comparisons due to the diverse sepsis knowledge quizzes used and differing ward settings where the studies were conducted (Nucera et al., 2018 ; Rahman et al., 2019 ; Stamataki et al., 2014 ; Storozuk et al., 2019 ; van den Hengel et al., 2016 ).

While our results showed that nurses displayed good awareness of sepsis risk factors, there is a significant lack of awareness of the updated sepsis‐3 definitions and epidemiological data of sepsis. This may suggest an underappreciation of the severity of sepsis as a life‐threatening medical condition, which could have a negative impact on patient outcomes. The findings also suggest a significant knowledge gap among nurses in recognizing tachypnoea as an early manifestation of sepsis, and other aspects of sepsis bundle including collection of blood cultures, serum lactate's thresholds and management of septic shock. This knowledge gap was observed to correspond with the participants' lower confidence in identifying, performing clinical assessment and initiating initial management of sepsis. The limited knowledge on sepsis care and lack of confidence were not surprising given that less than 15% of the participants reported receiving any education or training activities about sepsis in the past 1 year. However, it is encouraging that majority of the participants indicated their desire for further sepsis education and training, suggesting they were well aware of their knowledge deficit and the need to renew and advance their knowledge.

Our study showed that while those nurses who received sepsis education and training in the past 1 year had significantly higher confidence scores than those who did not, their knowledge scores were only marginally higher. This contrasts with findings in studies that have demonstrated improvement in nurses' attitudes, knowledge and confidence in recognizing and managing sepsis with sepsis education and training (Delaney et al., 2015 ; Edwards & Jones, 2021 ; O'Shaughnessy, 2017 ), and even more so if it was done recently (van den Hengel et al., 2016 ). One plausible reason for this could be related to the characteristics of the sepsis education and training activities (i.e. learning content, educational delivery method and teaching approach) that the participants had recently attended, which unfortunately was not captured in our questionnaire. We postulate that the methods of education and training delivery may have played an integral part in the learner's learning. This is supported by a recent systematic review of 32 international studies demonstrating sepsis education and training that incorporated active learning strategies were shown to enhance learners' knowledge retention and transfer of learning to clinical practice than didactic teaching (Choy et al., 2022 ). Nurses should therefore be provided with experiential learning opportunities such as simulation training or rotations to critical care areas with higher sepsis caseload. This allows them to apply their theoretical knowledge in practice, which can strengthen their competence and build their confidence levels.

In this study, factors such as nursing education level, clinical work area and job grade in recognizing and managing sepsis were found to be predictors of nurses' sepsis knowledge. Nurses who had attained a nursing specialization or a master's level education, worked in acute clinical areas such as ED/UCC or ICU/HDU, and held a more senior nursing position were found more likely to have better sepsis knowledge scores. This result is expected because teachings on sepsis for nurses without a specialization qualification—RNs with a diploma and/or bachelor's degree only—would be lacking in depth compared to nursing specialization programs and master's degree in nursing. For nurses without specialization, they would have limited exposure to sepsis education in their pre‐licensure nursing education curriculum, and further sepsis education and training programs would be usually dependent on their workplace training. Similar to Australia (Harley, Massey, et al., 2021 ), the apparent deficit in sepsis content in the pre‐licensure nursing curricula may be attributed to nursing curriculum planners being adaptable and responsive to the healthcare needs in Singapore. Key population health issues such as diabetes, stroke, mental health disorders and healthy aging have taken precedence. In addition, sepsis is a complex syndrome that may pose a challenge for educators to impart to nursing students who have limited clinical exposure. On the other hand, sepsis may have been given greater focus in the curriculum of higher nursing education. This may explain why nurses with higher educational levels have higher sepsis knowledge scores which was also found in Öztürk Birge et al. ( 2021 ).

Our findings show that nurses working in acute care areas such as the ED/UCC, HDU and ICU generally have higher sepsis knowledge and self‐confidence scores than general ward nurses, a result that echoes those of Stamataki et al. ( 2014 ). While there has been an observed increase in the prevalence of sepsis in general wards (Szakmany et al., 2016 ; Zaccone et al., 2017 ), nurses' exposure to sepsis is higher in ICU/HDU and ED. As patients with sepsis often develop multiple organ‐system failure that requires aggressive management and close monitoring, they are usually treated in the ICUs or HDUs (Evans et al., 2021 ). Furthermore, patients in ICUs or HDUs have an increased risk of acquiring nosocomial infections due to various risk factors such as severity of illness, invasive procedures and multiple invasive catheters (Mayr et al., 2014 ). In the ED, the triage nurses are often the first‐line responders to patients presenting with community‐onset sepsis which accounted for almost 90% of hospitalized cases with sepsis (Rhee et al., 2019 ). The exposure to high volume caseload in their daily clinical practice may have contributed to better knowledge on sepsis presentation and its initial management.

Our study observed a poor correlation between sepsis and knowledge test scores and self‐confidence. A possible explanation for this outcome is that knowledge test does not allow for direct conclusion on participants' abilities and skills to provide sepsis care in their respective work environment (Liaw et al., 2012 ). Instead, the use of objective measures to evaluate nurses' clinical competencies and skills should be considered. This may include using a simulation test with an assessor checklist, workplace‐based assessment or sepsis‐related performance indicators. In addition, self‐reported competence and confidence may be limited by a cognitive bias where participants may have reported themselves as being more capable than they really are (Kruger & Dunning, 1999 ).

There is a growing body of knowledge advocating the implementation of sepsis screening tools and sepsis care bundles, which have been demonstrated to improve the recognition and management of sepsis, and lead to better patient outcomes (Evans et al., 2021 ). In this study, almost 30% of the open comments were related to implementing a hospital sepsis screening tool and sepsis management bundle or algorithm and surrounded empowering ward nurses to initiate initial sepsis management within their capacity. This would be particularly helpful for nurses with little clinical experience or limited sepsis knowledge. However, it is noteworthy that this study found no association between sepsis screening tool and nurses' knowledge and confidence in recognizing sepsis symptoms and performing clinical assessment of patients with suspected sepsis. This is contrary to previous studies that found improved confidence among nurses in the identification of patients with sepsis with the implementation of a sepsis screening tool (Edwards & Jones, 2021 ). Our finding may be explained by 25% of the nurses lacking awareness of the sepsis screening tool; which prompted us to pay attention to the implementation and dissemination process of clinical protocols. It also underlines the importance of continuous education and sepsis training of ground staff so as to improve compliance with sepsis clinical protocols and achieve a synergistic effect (Damiani et al., 2015 ; Roberts et al., 2017 ).

4.1. Limitations

This study had a few limitations. First, the low response rate of 23.1% limits the generalisability of the study to a wider population of RNs working in acute‐tertiary hospitals and to community nurses. The study was conducted during the coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) pandemic period where nurses' low morale and fatigue might have influenced participation rate. Second, even though we attempted to test the application and analysis of sepsis knowledge using case scenarios questions, MCQs may not be an accurate representation of participants' sepsis knowledge and clinical competencies and skills. Third, an in‐depth exploration of nurses' experiences and perceptions around recognizing and managing patients with sepsis was not elicited through the survey, in which these insights may be valuable to inform local policies and enrich nursing educational packages.

5. CONCLUSION

Nurses are placed in an opportunistic position to recognize and manage patients with sepsis. In congruent with previous studies, this multi‐site study revealed gaps in nurses' clinical knowledge of sepsis recognition and management, albeit nurses working in the acute clinical areas such as ED/UCC, HDU and ICU had higher knowledge and confidence than general ward nurses. Sepsis screening tools and sepsis bundles have been identified by participants as useful adjuncts in clinical practice to facilitate nurses in timely recognition and management of patients with sepsis. This study augments the need for a stronger foundation in sepsis education and training programs for nurses and the implementation of systems improve nurses' knowledge and confidence in recognizing and managing sepsis.

With the ongoing research to understand the pathophysiology and immunological mechanisms of sepsis and approach in managing sepsis, nurse educators and academics are responsible to ensure that sepsis education content are in keeping with the latest evidence‐based knowledge and best practices. There is a need to review the current pre‐licensure nursing curriculum and the delivery of current sepsis educational programs in workplace‐based nursing education. In addition, we should consider adopting a multidisciplinary approach involving nurses, physicians and pharmacists to formulate nurse‐driven sepsis screening algorithms and sepsis care protocols that are specific to different clinical areas. Efforts should also be aimed at continuous education, regular reviews of clinical processes, clinical audits and feedback to ensure sustainability.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All the listed authors have (1) made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content and (3) given final approval of the version to be published.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was internally funded by the Lee Foundation Research Fellow Start Up Grant awarded by the Alice Lee Centre for Nursing Studies, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jan.15435 .

Supporting information

Supplementary File 1

Supplementary File 2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the 7 content experts for their time and invaluable expert opinions in content validating the sepsis questionnaire. We would also like to thank all the nurses who participated in this study. We extend our appreciation to Ms Diana Lau for contributing to the development of the sepsis questionnaire.

Chua, W. L. , Teh, C. S. , Basri, M. A. B. , Ong, S. T. , Phang, N. Q. Q. , & Goh, E. L. (2023). Nurses' knowledge and confidence in recognizing and managing patients with sepsis: A multi‐site cross‐sectional study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 79, 616–629. 10.1111/jan.15435

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

- Choy, C. L. , Liaw, S. Y. , Goh, E. L. , See, K. C. , & Chua, W. L. (2022). Impact of sepsis education for healthcare professionals and students on learner and patient outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of Hospital Infection, 122, 84–95. 10.1016/j.jhin.2022.01.004 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chua, W. L. , Legido‐Quigley, H. , Ng, P. Y. , McKenna, L. , Hassan, N. B. , & Liaw, S. Y. (2019). Seeing the whole picture in enrolled and registered nurses' experiences in recognizing clinical deterioration in general ward patients: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 95, 56–64. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.04.012 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Damiani, E. , Donati, A. , Serafini, G. , Rinaldi, L. , Adrario, E. , Pelaia, P. , Busani, S. , & Girardis, M. (2015). Effect of performance improvement programs on compliance with sepsis bundles and mortality: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational studies. PLoS ONE, 10(5), e0125827. 10.1371/journal.pone.0125827 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Delaney, M. M. , Friedman, M. I. , Dolansky, M. A. , & Fitzpatrick, J. J. (2015). Impact of a sepsis educational program on nurse competence. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 46(4), 179–186. 10.3928/00220124-20150320-03 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dellinger, R. P. , Carlet, J. M. , Masur, H. , Gerlach, H. , Calandra, T. , Cohen, J. , Gea‐Banacloche, J. , Keh, D. , Marshall, J. C. , Parker, M. M. , Ramsay, G. , Zimmerman, J. L. , Vincent, J. L. , & Levy, M. M. (2004). Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Critical Care Medicine, 32(3), 858–873. 10.1097/01.ccm.0000117317.18092.e4 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Edwards, E. , & Jones, L. (2021). Sepsis knowledge, skills and attitudes among ward‐based nurses. British Journal of Nursing, 30(15), 920–927. 10.12968/bjon.2021.30.15.920 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Evans, L. , Rhodes, A. , Alhazzani, W. , Antonelli, M. , Coopersmith, C. M. , French, C. , Machado, F. R. , McIntyre, L. , Ostermann, M. , Prescott, H. C. , Schorr, C. , Simpson, S. , Wiersinga, W. J. , Alshamsi, F. , Angus, D. C. , Arabi, Y. , Azevedo, L. , Beale, R. , Beilman, G. , … Levy, M. (2021). Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Medicine, 47(11), 1181–1247. 10.1007/s00134-021-06506-y [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Graneheim, U. H. , & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harley, A. , Massey, D. , Ullman, A. J. , Reid‐Searl, K. , Schlapbach, L. J. , Takashima, M. , Venkatesh, B. , Datta, R. , & Johnston, A. N. B. (2021). Final year nursing student's exposure to education and knowledge about sepsis: A multi‐university study. Nurse Education Today, 97, 104703. 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104703 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harley, A. , Schlapbach, L. J. , Lister, P. , Massey, D. , Gilholm, P. , & Johnston, A. N. B. (2021). Knowledge translation following the implementation of a state‐wide Paediatric Sepsis Pathway in the emergency department‐ a multi‐centre survey study. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 1161. 10.1186/s12913-021-07128-2 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- IBM Corp . (2019). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 26.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kruger, J. , & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self‐assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. 10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levy, M. M. , Rhodes, A. , Phillips, G. S. , Townsend, S. R. , Schorr, C. A. , Beale, R. , Osborn, T. , Lemeshow, S. , Chiche, J. D. , Artigas, A. , & Dellinger, R. P. (2015). Surviving Sepsis Campaign: Association between performance metrics and outcomes in a 7.5‐year study. Critical Care Medicine, 43(1), 3–12. 10.1097/ccm.0000000000000723 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liaw, S. Y. , Scherpbier, A. , Rethans, J.‐J. , & Klainin‐Yobas, P. (2012). Assessment for simulation learning outcomes: A comparison of knowledge and self‐reported confidence with observed clinical performance. Nurse Education Today, 32(6), e35–e39. 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.10.006 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mayr, F. B. , Yende, S. , & Angus, D. C. (2014). Epidemiology of severe sepsis. Virulence, 5(1), 4–11. 10.4161/viru.27372 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McDonald, C. M. , West, S. , Dushenski, D. , Lapinsky, S. E. , Soong, C. , van den Broek, K. , Ashby, M. , Wilde‐Friel, G. , Kan, C. , McIntyre, M. , & Morris, A. (2018). Sepsis now a priority: A quality improvement initiative for early sepsis recognition and care. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 30(10), 802–809. 10.1093/intqhc/mzy121 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Milano, P. K. , Desai, S. A. , Eiting, E. A. , Hofmann, E. F. , Lam, C. N. , & Menchine, M. (2018). Sepsis bundle adherence is associated with improved survival in severe sepsis or septic shock. West The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 19(5), 774–781. 10.5811/westjem.2018.7.37651 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nucera, G. , Esposito, A. , Tagliani, N. , Baticos, C. J. , & Marino, P. (2018). Physicians' and nurses' knowledge and attitudes in management of sepsis: An Italian study. Journal of Health and Social Sciences, 3(1), 13–26. 10.19204/2018/phys2 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O'Shaughnessy, J. (2017). CNE SERIES early sepsis identification. MEDSURG Nursing, 26(4), 248–252. [ Google Scholar ]

- Öztürk Birge, A. , Karabag Aydin, A. , & Köroğlu Çamdeviren, E. (2021). Intensive care nurses' awareness of identification of early sepsis findings. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 1–14. 10.1111/jocn.16116 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Paoli, C. J. , Reynolds, M. A. , Sinha, M. , Gitlin, M. , & Crouser, E. (2018). Epidemiology and costs of sepsis in the United States—An analysis based on timing of diagnosis and severity level. Critical Care Medicine, 46(12), 1889–1897. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003342 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Prescott, H. C. , & Angus, D. C. (2018). Enhancing recovery from sepsis: A review. JAMA, 319(1), 62–75. 10.1001/jama.2017.17687 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pruinelli, L. , Westra, B. L. , Yadav, P. , Hoff, A. , Steinbach, M. , Kumar, V. , Delaney, C. W. , & Simon, G. (2018). Delay within the 3‐hour surviving sepsis campaign guideline on mortality for patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Critical Care Medicine, 46(4), 500–505. 10.1097/ccm.0000000000002949 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rahman, N. A. , Chan, C. M. , Zakaria, M. I. , & Jaafar, M. J. (2019). Knowledge and attitude towards identification of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and sepsis among emergency personnel in tertiary teaching hospital. Australasian Emergency Care, 22(1), 13–21. 10.1016/j.auec.2018.11.002 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reinhart, K. , Daniels, R. , Kissoon, N. , Machado, F. R. , Schachter, R. D. , & Finfer, S. (2017). Recognizing sepsis as a global health priority—A WHO resolution. New England Journal of Medicine, 377(5), 414–417. 10.1056/NEJMp1707170 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rhee, C. , & Klompas, M. (2020). Sepsis trends: Increasing incidence and decreasing mortality, or changing denominator? Journal of Thoracic Disease, 12(Suppl 1), S89–S100. 10.21037/jtd.2019.12.51 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rhee, C. , Wang, R. , Zhang, Z. , Fram, D. , Kadri, S. S. , & Klompas, M. (2019). Epidemiology of hospital‐onset versus community‐onset sepsis in U.S. Hospitals and Association with mortality: A retrospective analysis using electronic clinical data. Critical Care Medicine, 47(9), 1169–1176. 10.1097/ccm.0000000000003817 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Roberts, N. , Hooper, G. , Lorencatto, F. , Storr, W. , & Spivey, M. (2017). Barriers and facilitators towards implementing the Sepsis Six care bundle (BLISS‐1): A mixed methods investigation using the theoretical domains framework. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine, 25(1), 96. 10.1186/s13049-017-0437-2 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Royal College of Physicians . (2017). National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2: Standardising the assessment of acute‐illness severity in the NHS . https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/national‐early‐warning‐score‐news‐2

- Rudd, K. E. , Johnson, S. C. , Agesa, K. M. , Shackelford, K. A. , Tsoi, D. , Kievlan, D. R. , Colombara, D. V. , Ikuta, K. S. , Kissoon, N. , Finfer, S. , Fleischmann‐Struzek, C. , Machado, F. R. , Reinhart, K. K. , Rowan, K. , Seymour, C. W. , Watson, R. S. , West, T. E. , Marinho, F. , Hay, S. I. , … Naghavi, M. (2020). Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet, 395(10219), 200–211. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rudd, K. E. , Kissoon, N. , Limmathurotsakul, D. , Bory, S. , Mutahunga, B. , Seymour, C. W. , Angus, D. C. , & West, T. E. (2018). The global burden of sepsis: Barriers and potential solutions. Critical Care Medicine, 22(1), 232. 10.1186/s13054-018-2157-z [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- See, K. C. (2022). Management of sepsis in acute care. Singapore Medical Journal, 63(1), 5–9. 10.11622/smedj.2022023 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seymour, C. W. , Gesten, F. , Prescott, H. C. , Friedrich, M. E. , Iwashyna, T. J. , Phillips, G. S. , Lemeshow, S. , Osborn, T. , Terry, K. M. , & Levy, M. M. (2017). Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for sepsis. New England Journal of Medicine, 376(23), 2235–2244. 10.1056/NEJMoa1703058 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Singapore Ministry of Health . (2020). Principal causes of death . https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources‐statistics/singapore‐health‐facts/principal‐causes‐of‐death

- Singer, M. , Deutschman, C. S. , Seymour, C. W. , Shankar‐Hari, M. , Annane, D. , Bauer, M. , Bellomo, R. , Bernard, G. R. , Chiche, J.‐D. , Coopersmith, C. M. , Hotchkiss, R. S. , Levy, M. M. , Marshall, J. C. , Martin, G. S. , Opal, S. M. , Rubenfeld, G. D. , van der Poll, T. , Vincent, J.‐L. , & Angus, D. C. (2016). The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis‐3). The Journal of the American Medical Association, 315(8), 801–810. 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stamataki, P. , Papazafiropoulou, A. , Kalaitzi, S. , Sarafis, P. , Kagialari, M. , Adamou, E. , Diplou, A. , Stravopodis, G. , Papadimitriou, A. , Giamarellou, E. , Karaiskou, A. , & Hellenic Sepsis Study, G . (2014). Knowledge regarding assessment of sepsis among Greek nurses. Journal of Infection Prevention, 15(2), 58–63. 10.1177/1757177413513816 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Storozuk, S. A. , MacLeod, M. L. P. , Freeman, S. , & Banner, D. (2019). A survey of sepsis knowledge among Canadian emergency department registered nurses. Australasian Emergency Care, 22(2), 119–125. 10.1016/j.auec.2019.01.007 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Szakmany, T. , Lundin, R. M. , Sharif, B. , Ellis, G. , Morgan, P. , Kopczynska, M. , Dhadda, A. , Mann, C. , Donoghue, D. , Rollason, S. , Brownlow, E. , Hill, F. , Carr, G. , Turley, H. , Hassall, J. , Lloyd, J. , Davies, L. , Atkinson, M. , Jones, M. , … Hall, J. E. (2016). Sepsis prevalence and outcome on the general wards and emergency departments in Wales: Results of a multi‐centre, observational, point prevalence study. PLoS One, 11(12), e0167230. 10.1371/journal.pone.0167230 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Torsvik, M. , Gustad, L. T. , Mehl, A. , Bangstad, I. L. , Vinje, L. J. , Damås, J. K. , & Solligård, E. (2016). Early identification of sepsis in hospital inpatients by ward nurses increases 30‐day survival. Critical Care, 20(1), 244. 10.1186/s13054-016-1423-1 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- van den Hengel, L. C. , Visseren, T. , Meima‐Cramer, P. E. , Rood, P. P. M. , & Schuit, S. C. E. (2016). Knowledge about systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis: A survey among Dutch emergency department nurses. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 9(1), 19. 10.1186/s12245-016-0119-2 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vincent, J.‐L. (2016). The clinical challenge of sepsis identification and monitoring. PLoS Medicine, 13(5), e1002022. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002022 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Woo, B. F. Y. , Zhou, W. , Lim, T. W. , & Tam, W. S. W. (2020, Jan). Registered nurses' perceptions towards advanced practice nursing: A nationwide cross‐sectional study. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(1), 82–93. 10.1111/jonm.12893 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zaccone, V. , Tosoni, A. , Passaro, G. , Vallone, C. V. , Impagnatiello, M. , Li Puma, D. D. , De Cosmo, S. , Landolfi, R. , & Mirijello, A. (2017, 2017/10/03). Sepsis in Internal Medicine wards: Current knowledge, uncertainties and new approaches for management optimization. Annals of Medicine, 49(7), 582–592. 10.1080/07853890.2017.1332776 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data availability statement.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (615.7 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

als and nursing students about identifying sepsis. 3 . 2 FOUNDATION OF THE STUDY : The foundation of the study describes the main concepts of this thesis which a include definition of sepsis, identification and assessment of sepsis and general view of nurses working in the emergency department.

Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2016 ... Doctor of Nursing Practice Walden University May 2016 . Abstract Sepsis is the leading cause of death among hospitalized patients in the United States, is responsible for more than 200,000 deaths annually, and has as high as a 50% mortality ...

Sepsis is a complication caused by the overwhelming and life-threatening response of the body to an infection. Sepsis can lead to tissue damage, organ failure, and death (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). Sepsis is the leading cause of death in U.S. hospitals. Mortality from sepsis increases 8% for every hour that treatment is ...

nursing staff on the 1-hour sepsis bundle. An increase in nursing staff knowledge in the emergency department may result in improved sepsis identification and improve sepsis intervention times. This could improve patient outcomes and increase national guideline compliance rates for the hospital. Problem Statement

Part of the Nursing Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies ... pursue my Doctor of Nursing Practice. Cheryl died from sepsis-related complication. Acknowledgments To my daughter, Toya G. Robinson, and my grandson Carter, thanks for your ...

The progression of sepsis is strongly influenced by the timing of interventions. The severity of sepsis increases when there are delays in interventions such as antibiotics (CDC, 2019). Sepsis is a major contributor to morbidities and mortalities in hospitalized settings. In fact, sepsis accounts for 20% of all inpatient hospital mortality annually

ABSTRACT Caring for a patient with suspected sepsis is a challenging nursing role. Early recognition and appropriate management of a patient with sepsis saves lives. Nurses play a fundamental role ...

The thesis aimed to provide information to nurses to prevent the risk of sepsis in the postop-erative unit. The purpose of the literature review was to provide relevant information to re- ... Follow evidence-based guidelines and monitoring patients' early signs of sepsis. Keywords (subjects) Nursing intervention, Sepsis, Prevention, Post ...

current sepsis definition. Sepsis has recently been redefined as a "Life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response" (Singer et al, 2016). There are more than 250,000 episodes of sepsis in the United Kingdom (UK) annually resulting in approximately 44,000 deaths (Daniels and Nutbeam 2017) .

However, only 369 (52.0%) could correctly define sepsis. Nurses' job grade, nursing education level and clinical work area were significant predictors of nurses' sepsis knowledge. Specifically, nurses with higher job grade, higher nursing education level or those working in acute care areas (i.e. emergency department, high dependency units or ...