0078021332

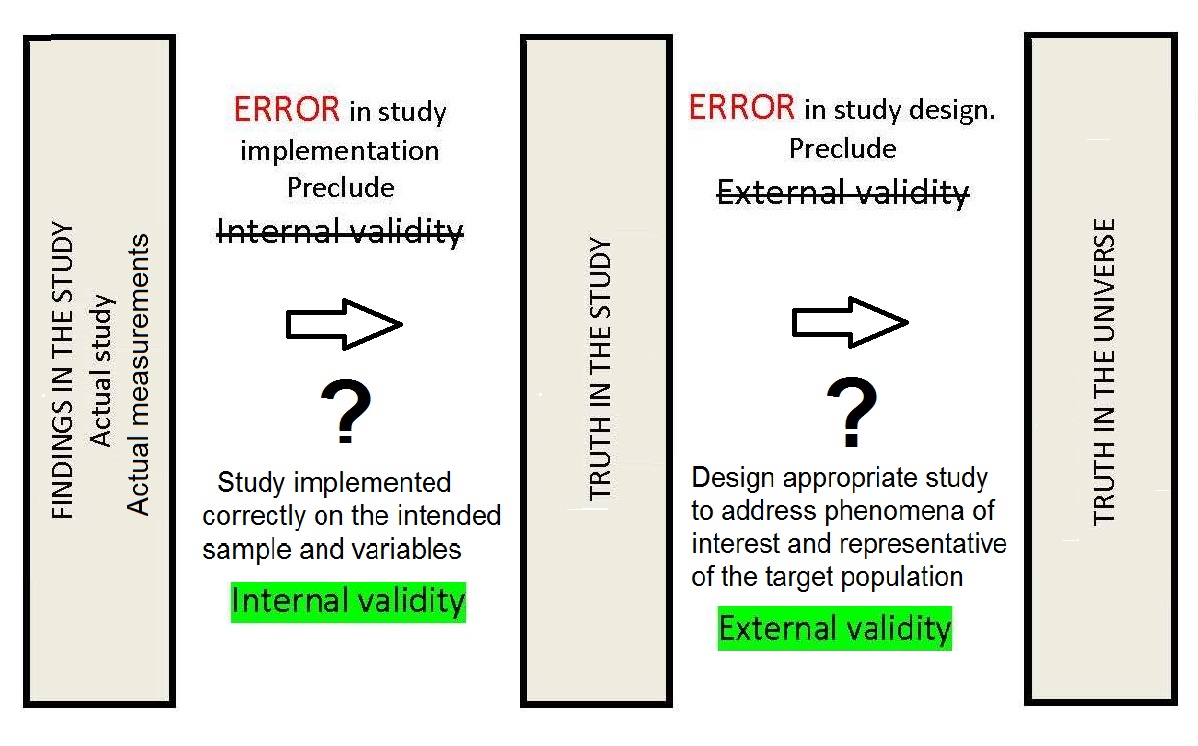

2013 Chronic, non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, stroke, and type 2 diabetes are among the leading causes of death globally, resulting in untold human suffering from premature morbidity and mortality. Left unchecked, the economic burden of chronic disease has the potential to cripple national economies. Because unhealthful dietary patterns (along with tobacco smoking and physical inactivity) are major risk factors for chronic disease, assessing diet and nutritional status and the results of interventions to improve nutritional status is fundamental to our success at reducing chronic disease risk, promoting health, and managing heath care costs. , Sixth Edition explains the tools and techniques that nutrition practitioners and other health care providers can use to assess diet and nutritional status in instances of acute illness as well as chronic disease prevention and treatment. Key features of this edition include: , and MyPlate.

| |

| | | Instructors: To experience this product firsthand, contact your . | | |

Copyright

Any use is subject to the and | |

Nutrition Assessment Forms: What to Include?- December 7, 2023

- Business Setup

Written by Olivia Farrow, RD, MHScReviewed by Maria Dellanina, RDN In the realm of nutrition care, a well-structured nutrition assessment is key to understanding and addressing a client’s unique needs. In this blog post, we’ll delve into the intricacies of nutrition assessment forms; what nutrition assessment entails and what to include in effective intake forms and chart notes to simplify the process. Understanding Nutrition AssessmentNutrition assessment is the first part of the nutrition care process; the “A” in ADIME. At its core, nutrition assessment is a systematic methodology, encompassing the collection, classification, and synthesis of pertinent data ( 1 ). This process is not a one-time event, but rather an ongoing, dynamic journey that involves initial data collection, continual reassessment, and analysis of a client’s status in relation to accepted standards, recommendations, and goals ( 1 ). Key Components of Nutrition Assessment:The nutrition care process includes 9 categories of nutrition assessment data ( 1 ). Each of these categories should be included on nutrition assessment forms, however the examples of data collected will depend on the individual client and practice setting ( 1 ): - Food/Nutrition-Related History: Delving into food and nutrient intake, administration, medication use, beliefs, attitudes, behavior, and more.

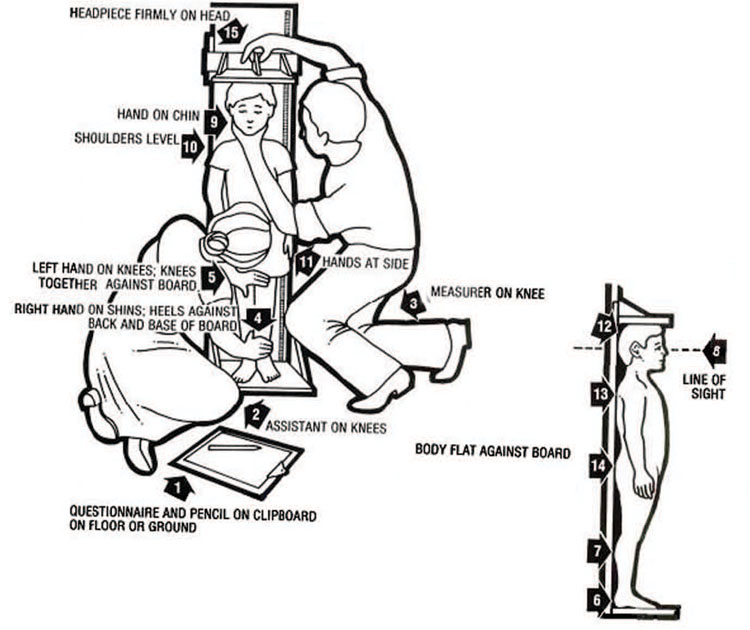

- Anthropometric Measurements: Considering body height, weight, frame, changes, and growth patterns.

- Biochemical Data, Medical Tests, and Procedures: Incorporating lab data, medical tests, and procedures.

- Physical Exam Findings: Evaluating findings from physical exams, interviews, or health records.

- Client History: Exploring personal, family, and social history.

- Assessment, Monitoring, and Evaluation Tools: Utilizing tools for health or disease status assessment.

- Etiology Category: Categorizing the type of nutrition diagnosis etiology.

- Comparative Standards: Establishing benchmarks for data comparison.

- Progress Evaluation: Assessing progress toward nutrition-related goals and resolution of nutrition diagnoses.

Where to Find Nutrition Assessment Data?The nutrition assessment data in each of the 9 categories, can be sourced before interacting with the client, through intake forms, health records, or information from referring or team healthcare providers. Data obtained before interacting with the client should always be confirmed during direct client interaction (or interactions with their substitute decision maker). During client interactions, additional data can be obtained directly from the client or based on observations during the session. Your Nutrition Assessment FormsNutrition assessment forms can be broken down into different components, which will likely include: - A data collection form; such as an initial intake form.

- A dietary intake form; a space for the client or practitioner to fill in food intake data.

- A chart note; the formal documentation space where the complete nutrition assessment will be outlined.

Having detailed intake form and chart note templates can help to support optimal nutrition assessment data collection. DSC has collaborated with Practice Better to provide you with a FREE form template bundle including: - Adult intake form

- Pediatric intake form

- Initial chart note template

- Follow-up chart note template

- 24-hour recall template

- 3-day food record template

Disclaimer: The form bundle was sponsored by Practice Better. Crafting Your Nutrition Assessment Forms The first part of your nutrition assessment forms is a space for gathering nutrition assessment data. This could be in the form of an intake form that the client fills out, a data collection form that you complete while interacting with the client and/or from the client’s data in their medical chart. To make your nutrition assessment simpler and more comprehensive, an intake or data collection nutrition assessment form might include: - Personal Information: contact details, reason for consultation (referral or request), relevant demographic and lifestyle information.

- Medical History: Conditions, surgeries, medications, allergies, supplement use, cognitive function data.

- Nutrition-focused physical findings: Physical symptoms related to nutrition such as appetite, swallowing, skin integrity, gastrointestinal symptoms, subjective global assessment.

- Biochemical Data : Including pertinent lab results and medical tests.

- Dietary Habits: Detailed insights into food preferences, meal patterns, and special dietary requirements. This might include a 24-hour recall, 3-day food record, or food frequency questions.

- Lifestyle Factors: Understanding physical activity (type and quantity of movement, sedentary activities, occupational related activity, ability to perform physical movements), sleep, and stress levels.

- Anthropometric Measurements: Height, weight (and source of data), weight history, how often weight is obtained, and relevant indices.

- S ocial and Cultural Factors: Factors affecting access to food, behaviors around food, social network, culturally related requirements around food or nutrition.

- Nutrition Knowledge and Attitudes: Level or areas of nutrition knowledge and food/health literacy, attitudes, beliefs, and relationship with food, readiness for change.

- Goals and Expectations: Exploring the client’s health and nutrition goals.

Your assessment might also include a validated screening tool such as a malnutrition screening tool, either as part of your nutrition assessment forms or separately.  Utilizing Your Nutrition Assessment DataAfter gathering all of the data you need for your nutrition assessment you will need to apply your critical thinking skills to interpret the data and conduct your assessment. Information gathering will also include meeting the client to understand and confirm the details of the pre-session data. Most of this part of your nutrition assessment will be housed in the assessment portion of your nutrition chart notes. A detailed chart note template can help you to ensure you don’t miss any important nutrition assessment details. An important part of your nutrition assessment is comparing the client’s data to comparative standards. These could be reference standards such as the dietary reference intakes (DRIs), recommendations (such as a practice guideline), or goals (i.e. the client has a specific habit or behavior they would like to modify). Once this step has been completed, you can put on your nutrition assessment hat and outline the main nutrition problem. This may require prioritization of the most severe problem if there are more than one. This nutrition problem will be directly used in your nutrition diagnosis; the “P” in PES Statement. For more information on PES Statements check out the blog article: How To Write a PES Statement (With Sample PES Statements!) and download our Free PES statement cheat sheet Key Takeaways- Nutrition assessment is a dynamic, systematic process and the first step in the nutrition care process.

- The nutrition care process includes nine categories, guiding the collection of important data.

- Effective nutrition assessment forms consist of a data collection form, dietary intake data form, and a formal chart note.

- Compare client data to standards, recommendations, or goals to identify and prioritize nutrition problems for effective intervention.

References:1. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Nutrition Terminology Reference Manual (eNCPT): Dietetics Language for Nutrition Care. “NCP Step 1: Nutrition Assessment”. (2023 Edition) https://www.ncpro.org/pubs/2023-encpt-en/category-1 Related Articles © 2024 Dietitian Success Center Terms & Conditions Privacy Policy Learn more about the membershipDietitian Success Center is your one-stop-shop to access affordable, evidence based nutrition courses & resources, plus business building tools without the price tag of a high-ticket business coach. Student or Intern? Learn about our student rate . Already a member? - What is Nutrition Assessment? [Methods & Free Templates]

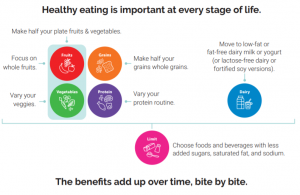

What is Nutritional Assessment? The British Dietetic Association (BDA) defines nutritional assessment as the systematic process of collecting and interpreting information in order to make decisions about the nature and cause of nutrition-related health issues that affect an individual. It can be done by a healthcare professional or self-assessment using online tools. This assessment involves measuring body weight, height, blood pressure, heart rate, waist circumference, muscle mass, bone density, and other factors that may affect how much food you need to consume. Based on the data gathered, one can make an informed decision on what a person needs to eat in order to achieve and maintain health. The goal of nutrition assessment is to determine if your diet meets your nutrient requirements, which are based on your age, gender, activity level, current medical conditions, medications, and lifestyle choices. If your diet falls below these requirements, you can make any required changes to improve your eating habits. Try this out: Dietary Assessment Questionnaire Template Importance of Nutritional AssessmentYou are what you eat. Committing to nutritional assessment helps you know what you should and should not be eating if you want to live a healthy life. Let’s look at some other reasons why you should prioritize nutritional assessment. - Nutritional assessment helps people understand their own dietary intake and how it compares with the recommended daily allowances for nutrients.

- Regular nutritional assessment allows you to identify any potential risks associated with poor nutrition.

- It helps people make informed decisions about changes to their diets.

- A nutritional assessment provides information about whether or not there are specific foods that you shouldn’t eat.

- It helps you learn how to plan meals and snacks ahead so you don’t have to rely on fast food or convenience options.

- Regular nutritional assessment is the only way to ensure you’re getting enough nutrients from your meals and in the right quantities.

Explore: Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire Template How Often Should Nutritional Assessment Happen? A nutrition assessment should be performed at least once every year, depending on the individual’s health and lifestyle. For example, if you’re trying to lose weight , you may want to do an assessment more frequently than someone who’s maintaining their normal weight. Objectives of Nutritional AssessmentThe objectives of a nutritional assessment depend on the context of the program and what you want to achieve. In the case of a one-on-one program with an individual, the common goal should be improving the health habits and overall lifestyle of the patient. Nutritional assessment should also identify and address any cases of possible malnutrition. Other common objectives are: - Nutritional assessment evaluates a person’s overall health and nutritional status.

- It identifies possible nutrient deficiencies in an individual

- Nutritional assessment allows the experts to evaluate the effectiveness of prescribed treatments.

- It’s an effective way to monitor progress toward goals set during treatment.

- It helps you to prevent malnutrition.

- It provides an opportunity for the experts to educate their patients about proper nutrition.

- Nutritional assessment promotes healthy lifestyles.

- It encourages compliance with recommendations for treatment.

Use for Free: Macros Calories Diet Plan Template Types of Nutritional Assessment1. anthropometric nutritional assessment . Anthropometric measurements are noninvasive quantitative measurements of the body that provide valuable assessments of the nutritional status of children and adults. Typically, it involves the measurement of the size, weight, and proportions of the body. Anthropometric measurements are commonly used in the pediatric population to evaluate the general health status, nutritional adequacy, and the growth and developmental pattern of the child. An important part of this type of nutritional assessment is weighing the individual and calculating their body-mass index to know if they fall within the optimal range. Common anthropometric measurements include: - Body Mass Index

- Waist Circumference

- Skinfold thickness

- Bone Mineral Density

- Blood Pressure

- Body Fat Percentage

- Other measures of adiposity

- Muscle mass

- Lean Body Mass

- Fat-Free Mass

- Total Body Water

- Visceral fat

- Fasting Blood Glucose

- Lipid profile

Use for Free: Weight Loss Tracking Form Template Advantages of Anthropometric Assessment - It uses simple, safe, and non-invasive procedures.

- Anthropometric assessment techniques can be applied to a large sample size

- It is objective with high sensitivity and specificity.

- It can be done by healthcare providers without specialized training.

Disadvantages of Anthropometric Assessment - An anthropometric assessment covers limited nutritional diagnosis.

- Anthropometric measurements cannot identify protein and micronutrient deficiencies or detect small disturbances in nutritional status.

2. Biochemical AssessmentBiochemical assessment involves checking the level of nutrients in a person’s blood, urine, or stool, usually through a lab test. These lab tests can help a trained medical practitioner discover any medical problems affecting your nutritional status or appetite. For example, a lab scientist might take your blood sample to measure the level of glucose in your body. During a full biochemical assessment, the physician will screen the following biochemical parameters: albumin, prealbumin, CRP, transferrin, hemoglobin, urea and creatine, lymphocytes, and point deficiencies. Advantages of Biochemical Assessment - They pick up the earliest indication of malnutrition or any nutritional deficiencies in the body.

- Biochemical assessments also confirm the clinical diagnosis of nutritional status and/ or risk for a disease.

Disadvantages of Biochemical Assessment - It is time-consuming.

- The health practitioner needs to run multiple biological tests for a proper diagnosis.

Use For Free: Caloric Calculator For Fat Loss Form Template 3. Clinical Nutritional AssessmentClinical assessment is the simplest and most practical method of ascertaining the nutritional well-being of a patient. In this case, the physician examines specific areas of the patient’s body to discover any signs of deficiencies. A clinical nutritional assessment also involves asking the patient whether they have any symptoms that might suggest nutrient deficiency from the patient. Advantages of Clinical Assessment - It helps the health practitioner dictate changes in the body’s metabolism.

Disadvantages of Clinical Assessment - It is expensive.

- It only provides limited data on food composition.

4. Dietary Assessment Dietary assessment is the process of collecting information about what a person eats and drinks over a period of time. In other words, it is a record of the foods one eats in an attempt to calculate their potential nutrient intake. During a dietary assessment , the health practitioner analyzes the energy, nutrients, and other dietary constituents using food composition tables. The goal of dietary assessment is to identify appropriate and actionable areas of change in the patient’s diet and lifestyle and to improve the overall wellbeing of the patient. For a detailed analysis, the health practitioner can deploy one or more of these methods: - Diet Record

- 24-hour recall

- Food Frequency Questionnaire

Advantages of Dietary Assessment - It provides contextual information about a person’s nutritional intake.

- Results from the dietary assessment are largely accurate due to more detailed descriptions of foods and portion sizes.

Disadvantages of Dietary Assessment - It relies on accurate recall of dietary intake over a long period of time.

- It is prone to misreporting, especially when the health practitioner adopts food frequency questionnaires for data gathering.

Nutritional Assessment Tools Let’s look at some tools that health practitioners use to determine an individual’s nutritional needs. - Food Frequency Questionnaire

A food frequency questionnaire is a tool that helps you record how often you eat certain foods on a regular basis. It also asks questions about your eating habits. This information can then be compared to national guidelines or standards. A food frequency questionnaire will help you keep track of what you eat regularly. You can fill it out at home or take it to your doctor’s office. The answers provided will help your doctor make the right decisions about your nutritional health. When filling out a food questionnaire, write down everything you ate during the past 24 hours. Include all beverages, including water, milk, juice, soda, tea, coffee, alcohol, and any other drinks. Also, note if you skipped meals. If you’re not sure whether something was eaten, just put an “X” next to the item. A calorie calculator allows you to fill in the number of calories you consume in a day. Then, based on your weight, age, gender, height, and activity level, it determines the number of calories you need each day for a healthy life. A calorie calculator is only as good as the measurements you input. For instance, some people might forget to include snacks, such as cookies, crackers, chips, etc., when they count calories. And they might underestimate the calories they burn while exercising. These inaccurate measurements affect the quality of information you get from the calculator in the end. To use a calorie calculator, follow these steps: 1. Enter your current weight. 2. Choose from five different activities levels. The higher the level, the greater the intensity of exercise. 3. Select the number of days you’d like to calculate your daily calorie needs. 4. Click Calculate. 5. Review the results and adjust them as needed. 6. Print out your results. A food pyramid shows you how many servings of grains, vegetables, fruits, dairy products, meat, and oils you should eat every day. Each section represents a specific type of food. For example, the top part of the pyramid shows you how much whole grain bread, pasta, rice, cereal, oatmeal, and potatoes you should eat. The bottom part shows you how much fruit, vegetable, fish, meats, and eggs you should eat. Formplus is a data collection tool that allows you to create surveys and questionnaires for nutritional assessment. It has several features that help you collect data from respondents seamlessly and conveniently. Let’s look at a few reasons why you should use Formplus for nutritional assessment. 1. Create Mobile-Friendly Forms Formplus allows you to create mobile-responsive nutritional assessment forms that can be filled out on any device including smartphones, laptops, and notepads. Formplus forms offer an optimized user experience and fit into any devices they are viewed on. 2. Easy-to-use Drag and Drop Form Builder With Formplus, it is really easy for you to create your online interview form template in minutes in the drag-and-drop form builder; without any technical knowledge. All you need to do is click on your preferred form fields or drag and drop them into the form builder to add them to your nutritional assessment form. 3. Analytics and Reports The form analytics feature makes it easier for you to process form responses collected through your nutritional assessment form. You can view insights on form responses in the analytics dashboard including the total number of submissions, average form response time, and the devices used to fill out your form. 4. Multiple Form Fields Options Formplus has over 30 dynamic form fields that allow you to collect different information from patients; ranging from health information to file uploads. This means that you can now gather all the information you need to make an objective nutritional assessment in little or no time. Conclusion Nutritional assessment is important in maintaining fitness and general wellbeing. This is why it should be prioritized using all the tools and learnings that the 21st century offers  Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free! - biochemical assessment

- calorie calculator

- dietary assessment

- dietary requirements

- food frequency questionnaire

- nutrition assessment

- busayo.longe

You may also like: Training Survey: Types, Template + [Question Example]Conducting a training survey, before or after a training session, can help you to gather useful information from training participants....  Diet Planning For Weight Loss: Types, Tips & Free TemplatesIn this article, we would be exploring different types of diet planning along with templates you can use to quickly get started. Job Evaluation: Definition, Methods + [Form Template]Everything you need to know about job evaluation. Importance, types, methods and question examples 33 Online Shopping Questionnaire + [Template Examples]Learn how to study users’ behaviors, experiences, and preferences as they shop items from your e-commerce store with this article Formplus - For Seamless Data CollectionCollect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..  Principles of Nutritional Assessment:3 rd Edition, April 2024 - Chapter 25b. Combs G.F. Jr. Selenium

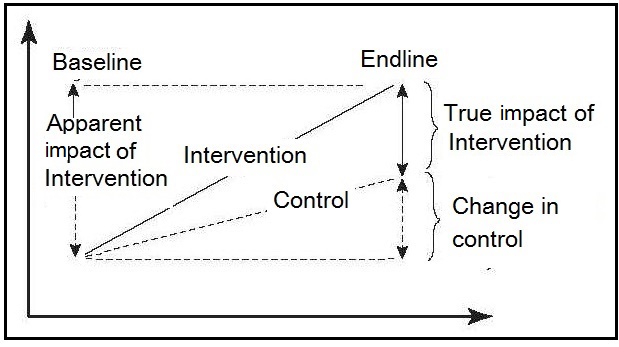

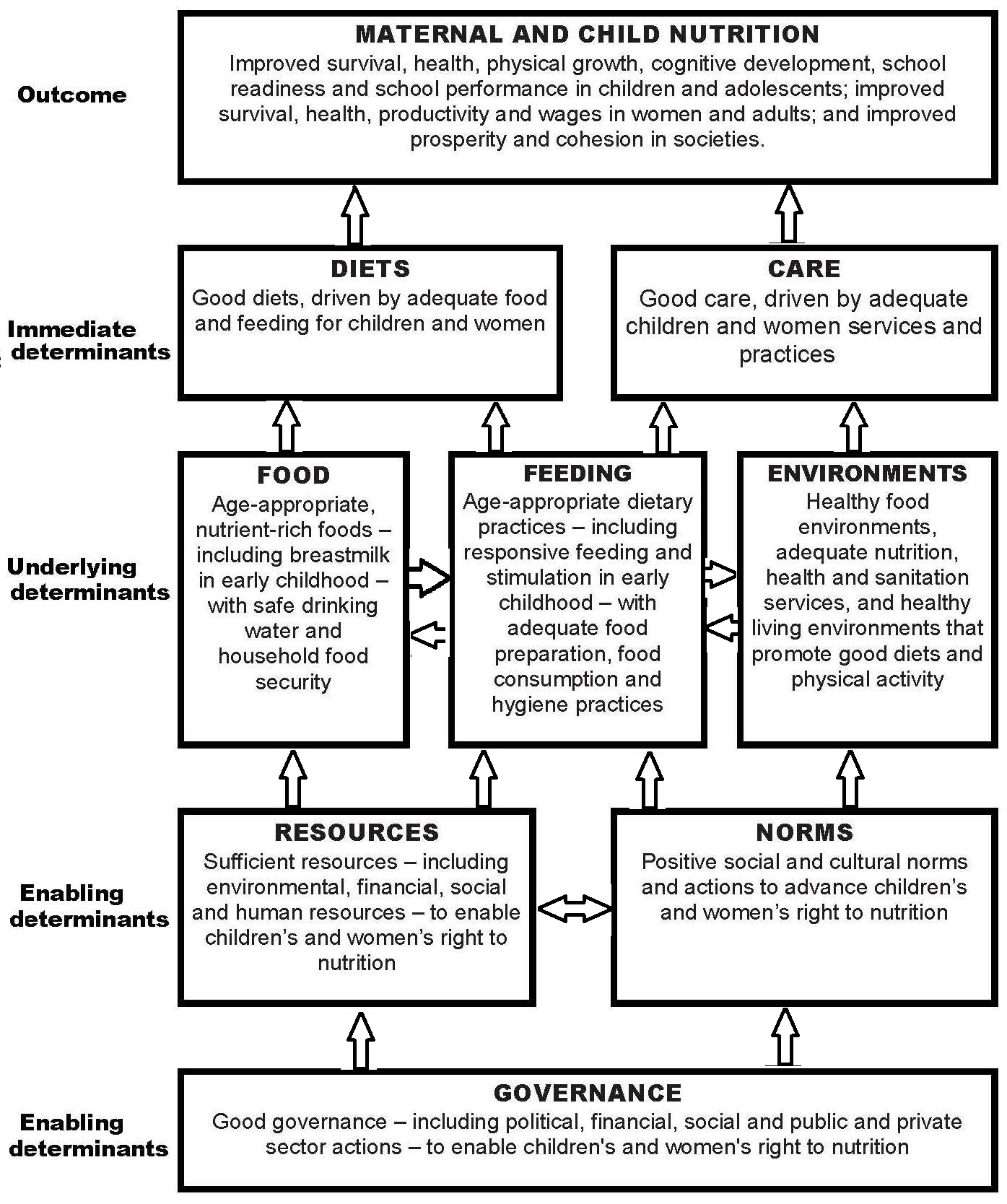

Nutritional Assessment: Introduction1.0 new developments in nutritional assessment. “the use of emerging information and communications technology, especially the internet, to improve or enable health and health care” “those designed for delivery through mobile phones” ( Olson, 2016 ). 1.1 Nutritional assessment systems1.1.1 nutrition surveys, 1.1.2 nutrition surveillance. - Give timely warning of the need for intervention to prevent critical deteriorations in food consumption.

- communicated effectively.

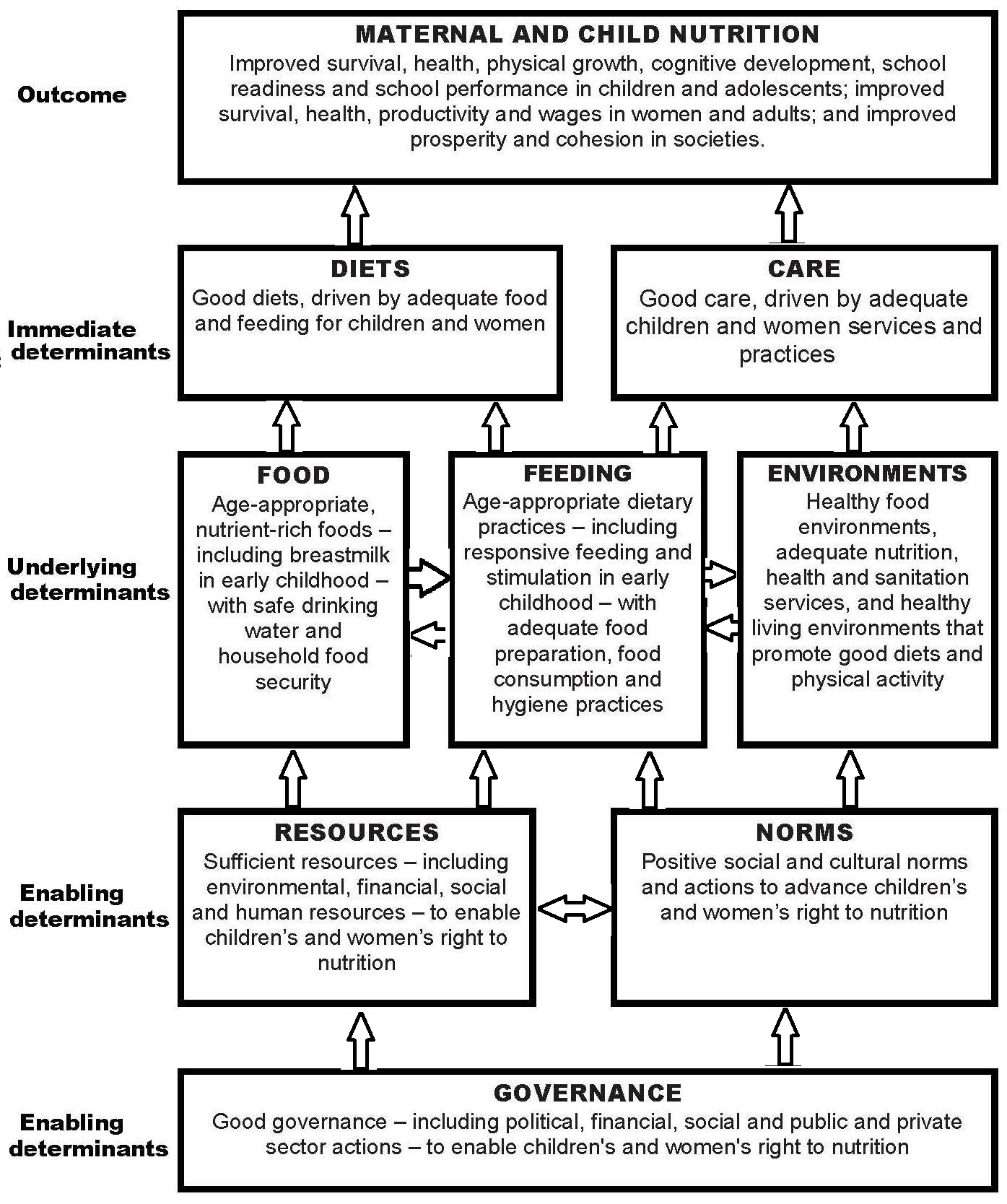

1.1.3 Nutrition screening1.1.4 nutrition interventions. - Pathway 3: Increased knowledge and adoption of optimal nutrition practices, including intake of micronutrient-rich foods (knowledge–adoption of optimal health- and nutrition-related practices pathway) and improve delivery, utilization, and potential for impact of a Homestead Food Production Program in Cambodia.

1.1.5 assessment systems in a clinical setting Table 1.1. Examples of personal goals in relation to personal nutrition. Data from van Ommen et al. ( ). | Goal | Definition |

|---|

Weight

management | Maintaining (or attaining) an ideal body weight

and/or body shaping that ties into heart, muscle,

brain and metabolic health | | Metabolic health | Keeping metabolism healthy today and tomorrow | | Cholesterol | Reducing and optimizing the balance between

high-density lipoprotein and low-density lipoprotein

cholesterol in individuals in whom this is disturbed | | Blood pressure | Reducing blood pressure in individuals who have

elevated blood pressure | | Heart health | Keeping the heart healthy today and tomorrow. | | Muscle | Having muscle mass and muscle functional abilities.

This is the physiological basis or underpinning of the

consumer goal of “strength” | | Endurance | Sustaining energy to meet the challenges of the

day (e.g., energy to do that report at work, energy

to play soccer with your children after work) | | Strength | Feeling strong within yourself,

avoiding muscle fatigue | | Memory | Maintaining and attaining an optimal short-term

and/or working memory | | Attention | Maintaining and attaining optimal focused and

sustained attention (i.e., being “in the moment” and

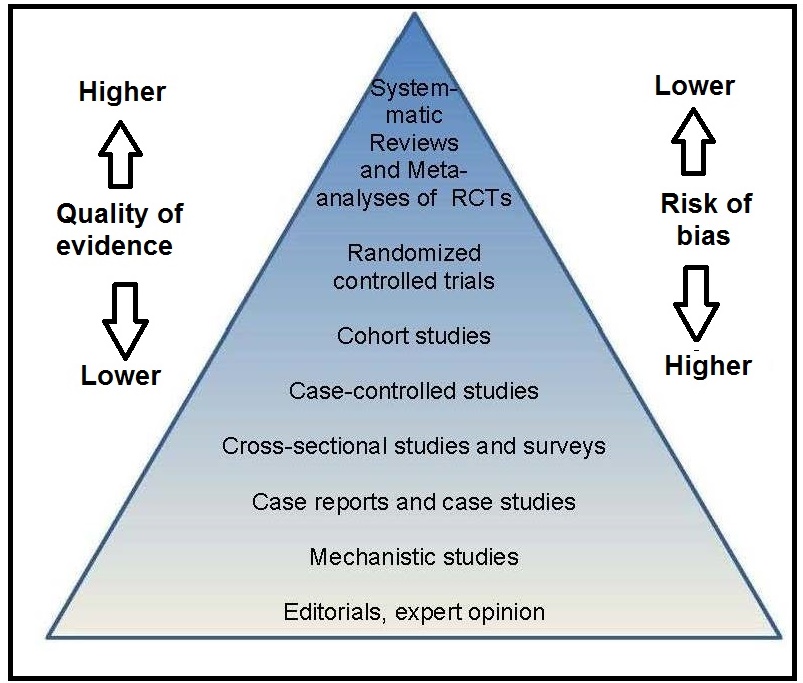

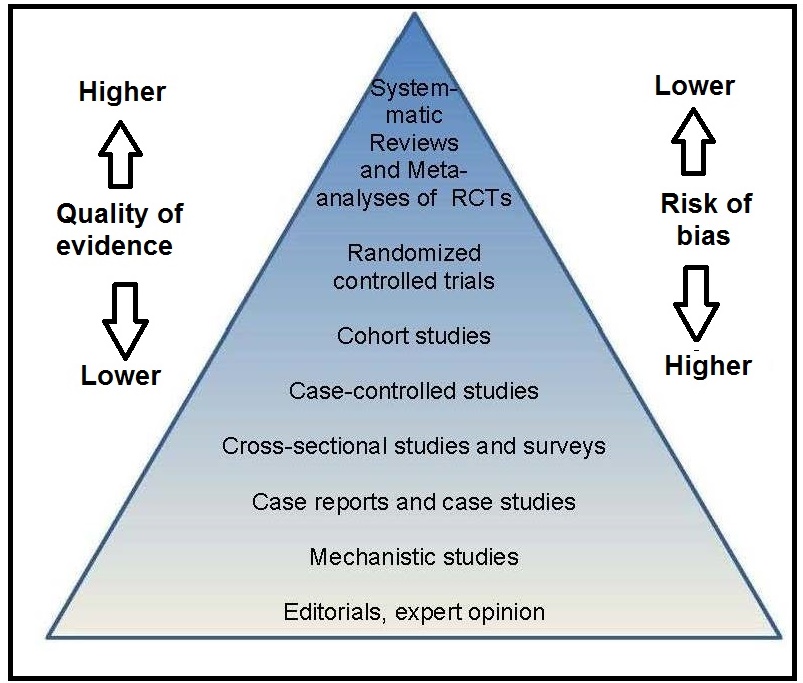

able to utilize information from that “moment”) | 1.1.6 Approaches to evaluate the evidence from nutritional assessment studies Table 1.2 Applying systemmatic reviews to nutrition questions: approaches to the challenges. Data from Brannon ( ). | Challenge | Approach |

|---|

| Baseline exposure | Unlike drug exposure, most persons have

some level of dietary exposure to the

nutrient or dietary substance of interest,

either from food or supplements, or

by endogenous synthesis in the case of

vitamin D, information on background

intakes and the methodologies used to assess

them should be captured in the

SR so that any related uncertainties can be

factored into data interpretation. | | Nutrient status | The nutrient status of an individual

or population can affect the response

to nutrient supplementation. | Chemical form

of the nutrient

or dietary substance | If nutrients occur in multiple forms, the forms

may differ in their biological activity.

Assuring bioequivalence or making

use of conversion factors can be

critical for appropriate data interpretation. | Factors that influence

bioavailability | Depending upon the nutrient or dietary

substance, influences such as

nutrient-nutrient interactions, drug

or food interactions, adiposity, or

physiological state such as pregnancy

may affect the utilization of the nutrient.

Capturing such information allows

these influences to be factored into

conclusions about the data. | Multiple and

interrelated biological

functions of a

nutrient or

dietary substance | Biological functions need to be understood

in order to ensure focus and to define

clearly the nutrient- or dietary

substance—specific scope of the review. | Nature of nutrient

or dietary substance

intervention | Food-based interventions require detailed

documentation of the approaches

taken to assess nutrient or dietary

substance intake. | Uncertainties in

assessing dose-

response

relationships | Specific documentation of measurement

and assay procedures is required to

account for differences in health outcomes. | 1.2 Nutritional assessment methods1.2.1 dietary methods. - An Overview of the Main Pre-Survey Tasks Required for Large-Scale Quantitative 24-Hour Recall Dietary Surveys in LMICs ( Vossenaar et al., 2020 )

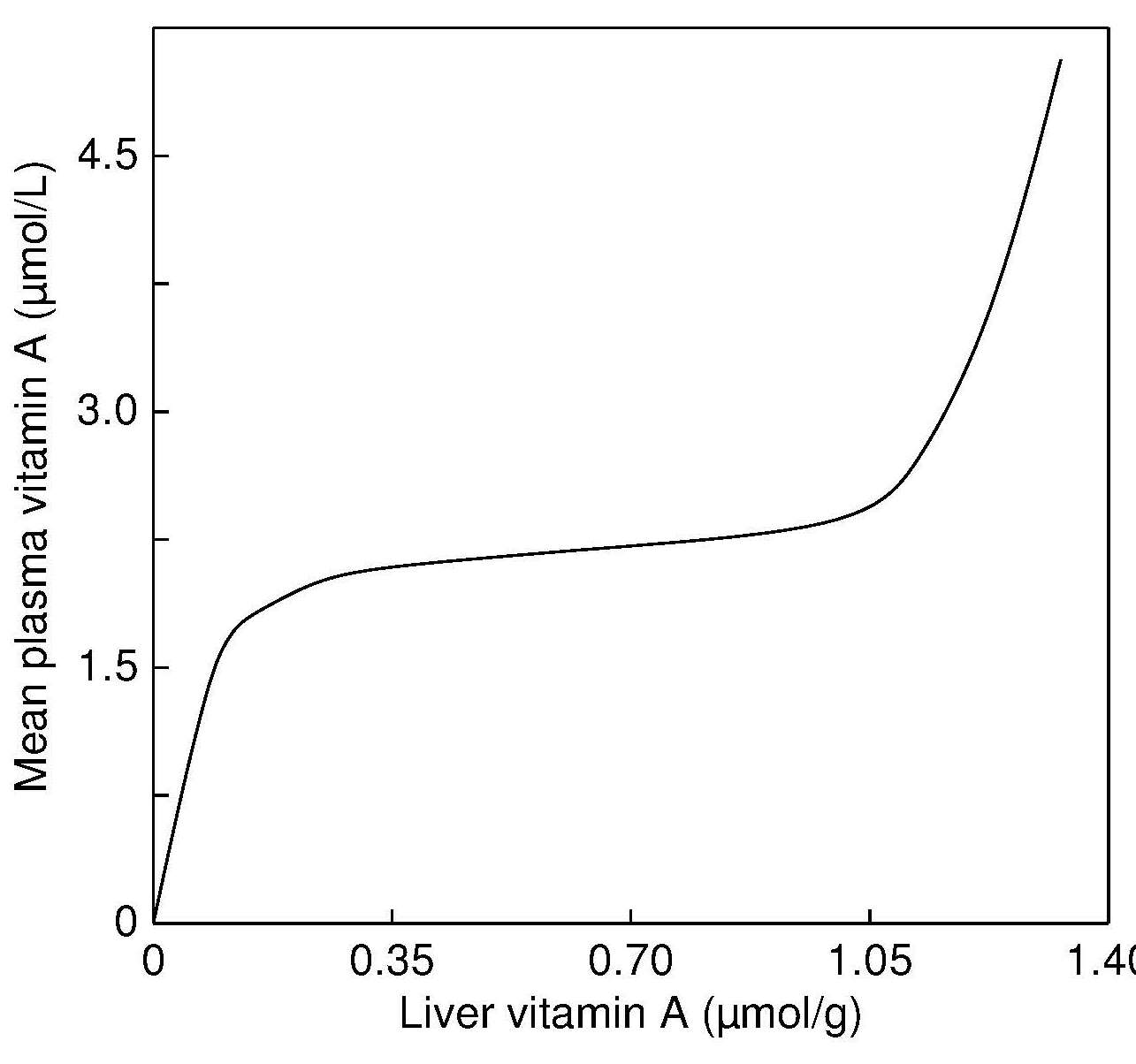

1.2.2 Laboratory Methods“a biological characteristic that can be objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological or pathogenic processes, and/or as an indicator of responses to nutrition interventions”. - Traditional dietary assessment methods

- Dietary biomarkers: indirect measures of nutrient exposure

- Biomarkers of “status”: body fluids (serum, erythrocytes, leucocytes, urine, breast milk); tissues (hair, nails)

- Functional biochemical: enzyme stimulation assays; abnormal metabolites; DNA damage. These biomarkers serve as early biomarkers of subclinical deficiencies.

- Functional physiological/behavioral: more directly related to health status or disease such as vision, growth, immune function, taste acuity, cognition, depression. These biomarkers impact on clinical and health outcomes.

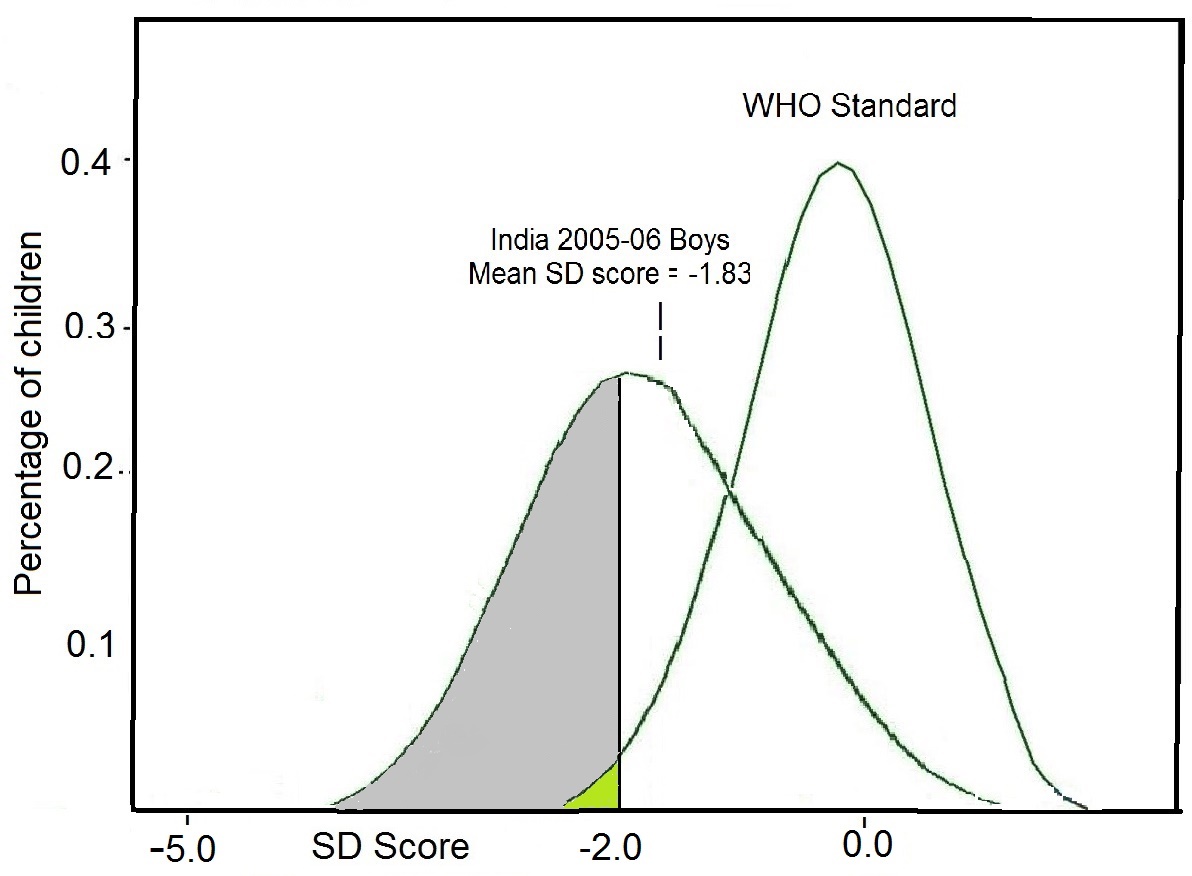

1.2.3 Anthropometric methods1.2.4 clinical methods, 1.2.5 ecological factors.  1.3 Nutritional assessment indices and indicators Table 1.3. Examples of dietary, anthropometric, laboratory, and clinical indicators and their application. EAR, estimated average requirement; IDD, iodine deficiency disorders. | Nutritional indicator | Application |

|---|

| | | Prevalence of the population with zinc intakes

below the estimated average requirement (EAR) | Risk of zinc deficiency

in a population | Proportion of children 6–23mos of age who

receive foods from 4 or more food groups | Prevalence of minimum

dietary diversity | | | | Proportion of children age 6–60mos in the population

with mid-upper arm circumference < 115mm | Risk of severe acute

malnutrition in the population | Percentage of children < 5y with

length- or height-for-age less than −2.0 SD below

the age-specific median of the reference population | Risk of zinc deficiency

in the population | | | | Percentage of population with serum Zn concentrations

below the age/sex/time of day-specific lower cutoff | Risk of zinc deficiency

in the population | Percentage of children age 6–71mos in the

population with a serum retinol < 0.70µmol/L | Risk of vitamin A

deficiency in the population | Median urinary iodine <20µg/L based on > 300

casual urine samples | Risk of severe IDD

in the population | Proportion of children (of defined age and sex) with

two or more abnormal iron indices (serum ferritin,

erythrocyte protoporphyrin, transferrin receptor)

plus an abnormal hemoglobin | Risk of iron deficiency

anemia in the population | | | | | Prevalence of goiter in school-age children ≥ 30% | Severe risk of IDD among the

children in the population | | Prevalence of maternal night blindness ≥ 5% | Vitamin A deficiency is a severe

public health problem | 1.4 The design of nutritional assessment systems1.4.1 study objectives and ethical issues. - Determining the overall nutritional status of a population or subpopulation

- Identifying areas, populations, or subpopulations at risk of chronic malnutrition

- Characterizing the extent and nature of the malnutrition within the population or subpopulation

- Identifying the possible causes of malnutrition within the population or subpopulation

- Designing appropriate intervention programs for high-risk populations or subpopulations

- Monitoring the progress of changing nutritional, health, or socioeconomic influences, including intervention programs

- Evaluating the efficacy and effectiveness of intervention programs

- Tracking progress toward the attainment of long-range goals.

- Confidentiality is adequately protected.

- Describe the procedures that provide answers to any questions and further information about the study.

1.4.2 Choosing the study participants and the sampling protocol- Quota sampling involves dividing the target population into a number of different categories based on age, ownership of land, or occupations etc, and taking a certain number of consenting individuals from each category into the final sample.

- Selecting participants who are accessible by road introduces a “tarmac” bias. Areas accessible by road are likely to be systematically different from those that are more difficult to reach.

- random sampling requires defining a number of levels of sampling, from each of which is drawn a random sample.

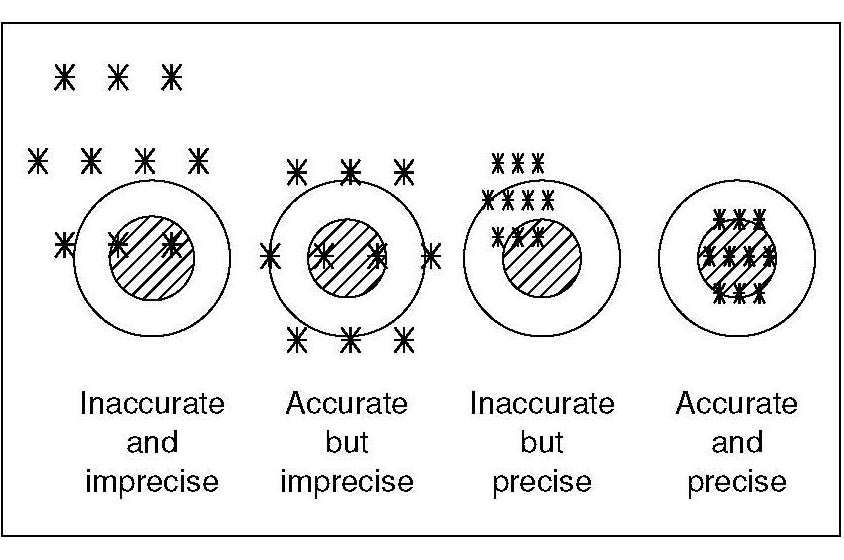

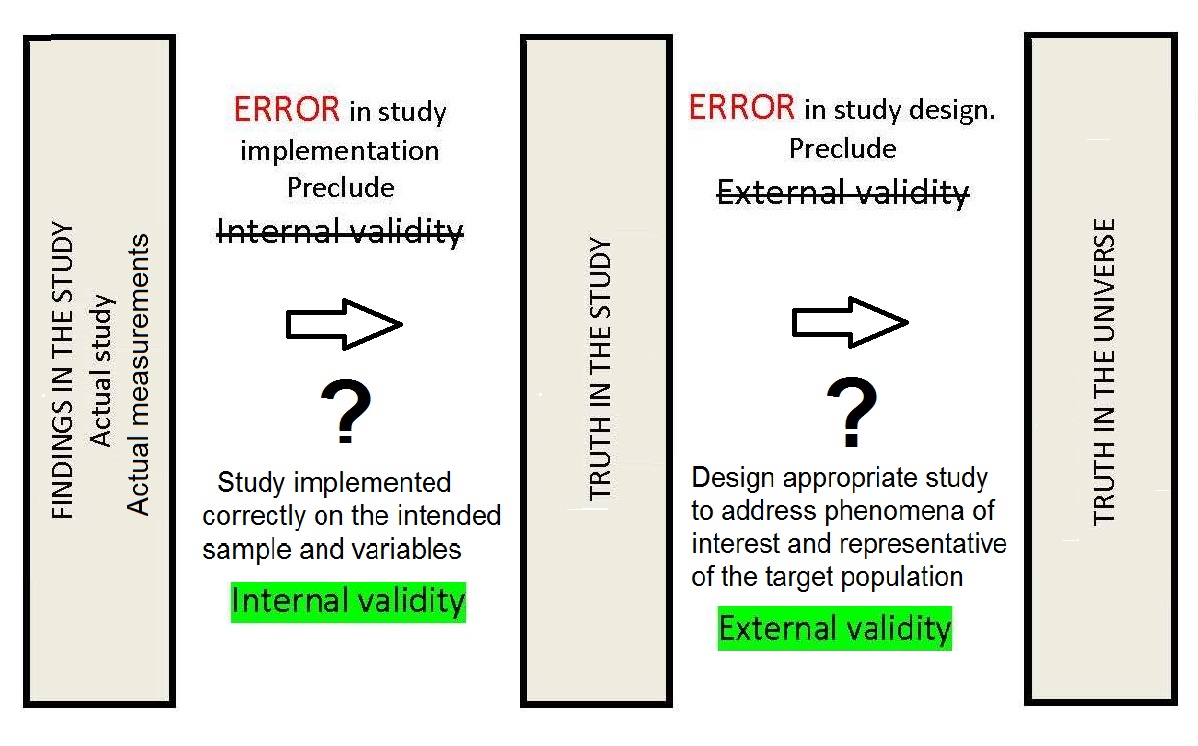

1.4.3 Calculating sample size1.4.4 collecting the data, 1.4.5 additional considerations, 1.5 important characteristics of assessment measures, 1.5.1 validity.  1.5.2 Reproducibility or precision- Coefficient of Reliability

Table 1.4 Within-person and analytical variance components for some common biochemical measures. Abstracted from Gallagher et al. ( ). | Coefficient of variation (%) |

|---|

| Measurement | Within-person | Analytical |

|---|

| Serum retinol | | | | Daily | 11.3 | 2.3 | | Weekly | 22.9 | 2.9 | | Monthly | 25.7 | 2.8 | | Serum ascorbic acid | | | | Daily | 15.4 | 0.0 | | Weekly | 29.1 | 1.9 | | Monthly | 25.8 | 5.4 | | Serum albumin | | | | Daily | 6.5 | 3.7 | | Weekly | 11.0 | 1.9 | | Monthly | 6.9 | 8.0 | - Reducing the effect of random errors from any source by repeating all the measurements, when feasible, or at least on a random subsample.

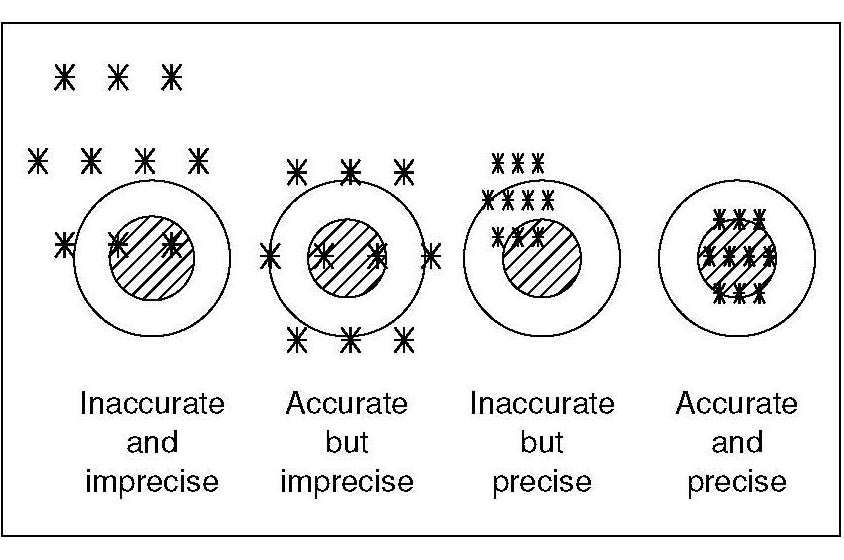

1.5.3 Accuracy Table 1.5 Precision and accuracy of measurements. | Precision or reproducibility | Accuracy |

|---|

| Definition | The degree to which repeated measurements

of the same variable give the same value | The degree to which a measurement is close to

the true value | | Assess by | Comparison among repeated measures | Comparison with certified reference materials,

criterion method, or criterion anthropometrist | | Value to study | Increases power to detect effects | Increases validity of conclusions | Adversely

affected by | Random error contributed by

the measurer,

the respondent, or

the instrument | Systematic error (bias) contributed by:

the measurer,

the respondent, or

the instrument | 1.5.4 Random errors1.5.5 Systematic errors or bias- Drop-out bias is usually the result of ignoring possible systematic differences between those who fail to complete a study and the remaining participants.

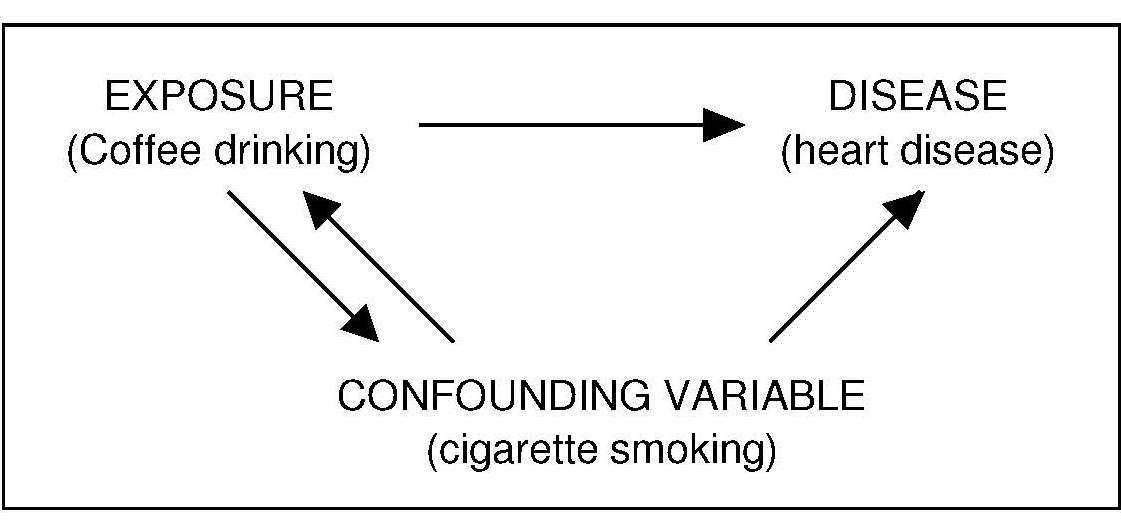

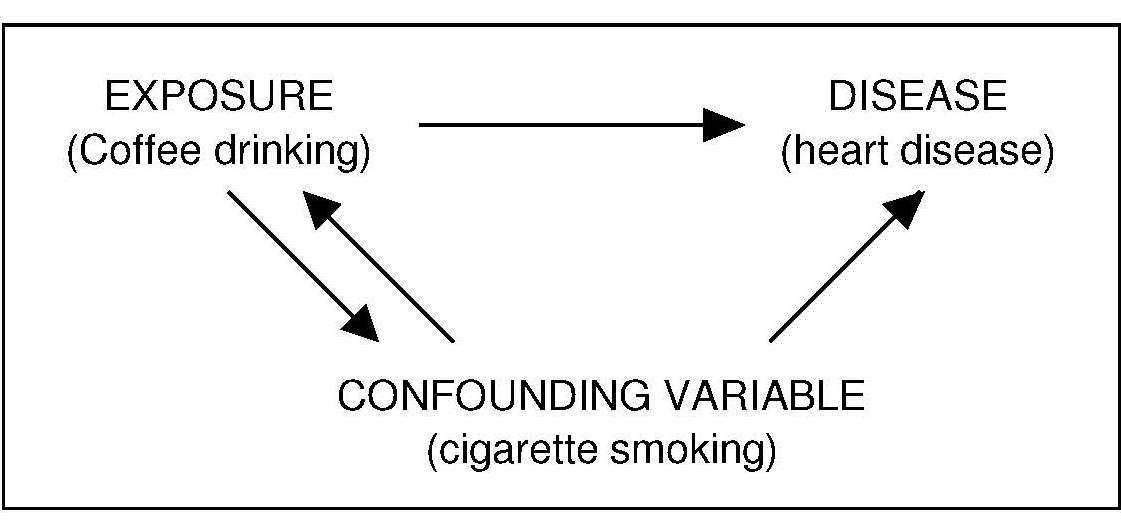

1.5.6 Confounding- A confounder cannot be an intermediary step in the causal pathway from the exposure of interest to the outcome of interest.

1.5.7 Sensitivity 1.5.8 Specificity Table 1.6: Numerical definitions of sensitivity, specificity, predictive value, and prevalence for a single index used to assess malnutrition in a sample group.

Sensitivity (S ) = TP / (TP+FN)

Specificity (S ) = TN / (FP+TN)

Predictive value (V) = (TP+TN) / (TP+FP+TN+FN)

Positive predictive value (V+) = TP / (TP+FP)

Negative predictive value (V−) = TN / (TN+FN)

Prevalence (P) = (TP+FN) / (TP+FP+TN+FN)

From Habicht ( ). Test

result | The true situation:

Malnutrition present | The true situation:

No malnutrition |

|---|

| Positive | True positive (TP) | False positive (FP) | | Negative | False negative (FN) | True negative (TN) | Table 1.7. Sensitivity, specificity, and relative risk of death associated with various values for mid-upper-arm circumference in children 6–36mos in rural Bangladesh. Data from Briend et al. ( ). Arm circum-

ference (mm) | Sensitivity

(%) | Specificity

(%) | Relative Risk

of death |

|---|

| ≤ 100 | 42 | 99 | 48 | | 100–110 | 56 | 94 | 20 | | 110–120 | 77 | 77 | 11 | | 120–130 | 90 | 40 | 6 | Table 1.8. Impact of inflammation on micronutrient biomarkers of Indonesian infants of age 12mos. From Diana et al. ( ).

* Ferritin < 12µg/L

** RBP < 0.83µmol/L

*** Zinc < 9.9µmol/L | Biomarker in serum | Geometric mean (95% CI) | Proportion

at risk (%) | | Ferritin*: No adjustment | 14.5µg/L (13.6–17.5) | 44.9 | | Ferritin: Brinda adjustment | 8.8µg/L (8.0–9.8) | 64.9 | Retinol binding protein**:

No adjustment | 0.98 (µmol/L) (0.94–1.01) | 24.3 | Retinol binding protein:

Brinda adjustment | 1.07µmol/L (1.04–1.10) | 12.4 | | Zinc***: No adjustment | 11.5µmol/L (11.2–11.7) | 13.0 | | Zinc: Brinda adjustment | 11.7µmol/L (11.4–12.0) | 10.4 | 1.5.9 Prevalence1.5.10 predictive value. Table 1.9 Influence of disease prevalence on the predictive value of a test with sensitivity and specificity of 95%. From Dempsey and Mullen ( ). | Predictive Value | Prevalence

0.1% 1% 10% 20% 30% 40% | | Positive | 0.02 0.16 0.68 0.83 0.89 0.93 | | Negative | 1.00 1.00 0.99 0.99 0.98 0.97 | 1.6 Evaluation of nutritional assessment indices1.6.1 reference distribution. - REFERENCE INDIVIDUALS ↓ make up a

- REFERENCE population ↓ from which is selected a

- REFERENCE SAMPLE GROUP ↓ on which are determined

- REFERENCE VALUES ↓ on which is observed a

- REFERENCE Distribution ↓ from which are calculated

- REFERENCE LIMITS ↓ that may define

- REFERENCE INTERVALS

1.6.2 Reference limits1.6.3 cutoff points.  1.6.4 Trigger levels for surveillance and public health decision making Table 1.10. Prevalence thresholds, corresponding labels, and the number of countries (n) in different prevalence threshold categories for wasting, overweight and stunting in children under 5 years using the “novel approach”. From de Onis et al. ( ). | Wasting | overweight | Stunting |

|---|

Prevalence

thresholds

(%) | Labels | (n) | Prevalence

thresholds

(%) | Labels | (n) | Prevalence

thresholds

(%) | Labels | (n) |

|---|

| < 2·5 | Very low | 36 | < 2·5 | Very low | 18 | < 2·5 | Very low | 4 | | 2·5 – < 5 | Low | 33 | 2·5 – < 5 | Low | 33 | 2·5 – < 10 | Low | 26 | | 5 – < 10 | Medium | 39 | 5 – < 10 | Medium | 50 | 10 – < 20 | Medium | 30 | | 10 – < 15 | High | 14 | 10 – < 15 | High | 18 | 20 – < 30 | High | 30 | | ≥ 15 | Very high | 10 | ≥ 15 | Very high | 9 | ≥ 30 | Very high | 44 | - Prevalence of serum zinc less than age/sex/time-of-day specific cutoffs is > 20%

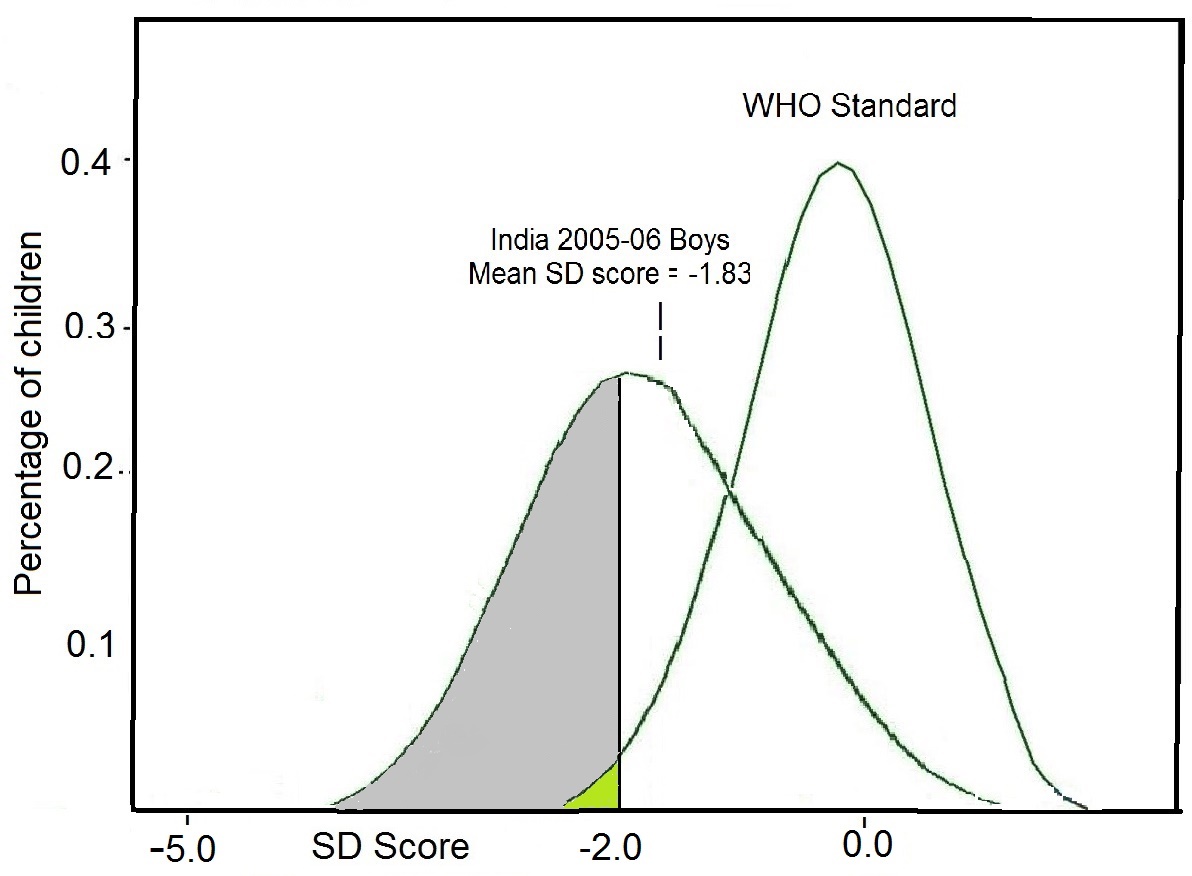

- Prevalence of inadequate zinc intakes below the appropriate Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) is > 25%

- Prevalence of low height-for-age or length-for-age Z‑scores (i.e., < −2SD) is at least 20%.

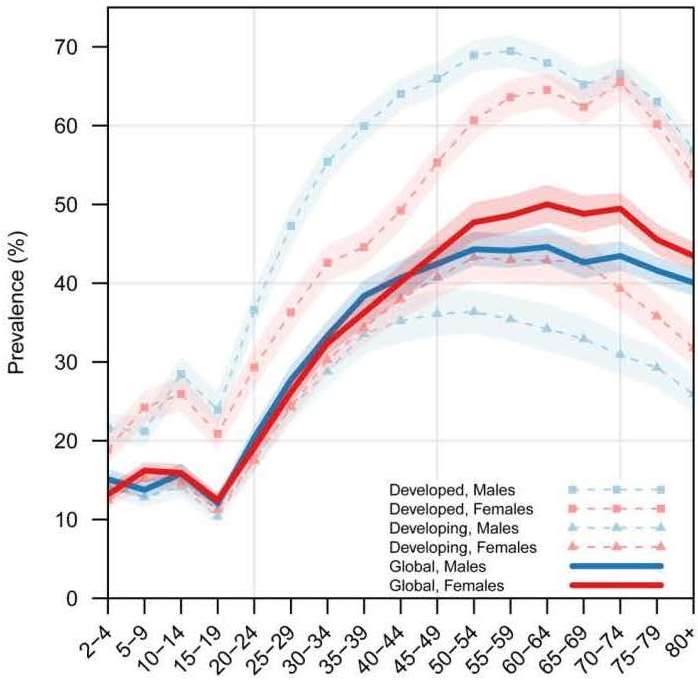

Nutritional Status: An Overview of Methods for Assessment- First Online: 02 April 2017

Cite this chapter - Catherine M. Champagne PhD (RDN, LDN, FADA, FAND, FTOS) 6 &

- George A. Bray M.D. 7

Part of the book series: Nutrition and Health ((NH)) 2389 Accesses This chapter focuses on the whole area of nutritional assessment and explores the wide spectrum of testing available that can aid in determining the health of an individual. This process typically includes in-depth evaluation of both subjective data and objective evaluations of an individual’s food and nutrient intake, components of lifestyle, and medical history. A nutritional assessment provides an overview of nutritional status; it focuses on nutrient intake analysis of the diet, which is then compared with blood tests and physical examination. With comprehensive data on diet and biological information, the physician can make an accurate estimate of that person’s nutritional status. Decisions can then be made on an appropriate plan of action to either maintain current health status or referral to counseling or other interventions that may enable the individual to reach a more healthy state. Only with sufficient anthropometric, biochemical, clinical, and dietary information can a plan be drafted. This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access. Access this chapter- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout Purchases are for personal use only Institutional subscriptions Similar content being viewed by others The Nutrition Assessment of Metabolic and Nutritional Balance Nutritional Status Evaluation: Body Composition and Energy BalanceOgden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:806–14. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;(219):1–8. Google Scholar Flegal KM, Panagiotou OA, Graubard BI. Estimating population attributable fractions to quantify the health burden of obesity. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25:201–7. Article PubMed Google Scholar Blanton CA, Moshfegh AJ, Baer DJ, Kretsch MJ. The USDA automated multiple-pass method accurately estimates group total energy and nutrient intake. J Nutr. 2006;136:2594–9. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Ahluwalia N, Dwyer J, Terry A, Moshfegh A, Johnson C. Update on NHANES dietary data: focus on collection, release, analytical considerations, and uses to inform public policy. Adv Nutr. 2016;7:121–34. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Bray GA. Review of: good calories, bad calories by Gary Taubes. New York: AA Knopf; 2007. Obes Rev. 2008;9:251–63. Article Google Scholar Archer E, Hand GA, Blair SN. Validity of U.S. nutritional surveillance: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey caloric energy intake data, 1971–2010. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76632. Tooze JA, Vitolins MZ, Smith SL, et al. High levels of low energy reporting on 24-hour recalls and three questionnaires in an elderly low-socioeconomic status population. J Nutr. 2007;137:1286–93. Shaneshin M, Jessri M, Rashidkhani B. Validity of energy intake reports in relation to dietary patterns. J Health Popul Nutr. 2014;32:36–45. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Scagliusi FB, Ferriolli E, Lancha Jr AH. Underreporting of energy intake in developing nations. Nutr Rev. 2006;64(7 Pt 1):319–30. Balkau B, Deanfield JE, Despres JP, et al. International Day for the Evaluation of Abdominal Obesity (IDEA): a study of waist circumference, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus in 168,000 primary care patients in 63 countries. Circulation. 2007;116:1942–51. Bray GA. Contemporary diagnosis and management of obesity. 3rd ed. Newtown: Handbooks in Health Care Co; 2003. Rothney MP, Brychta RJ, Schaefer EV, Chen KY, Skarulis MC. Body composition measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry half-body scans in obese adults. Obesity. 2009;17:1281–6. Lazzer S, Bedogni G, Agosti F, De Col A, Mornati D, Sartorio A. Comparison of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, air displacement plethysmography and bioelectrical impedance analysis for the assessment of body composition in severely obese Caucasian children and adolescents. Br J Nutr. 2008;18:1–7. Shypailo RJ, Butte NF, Ellis KJ. DXA: can it be used as a criterion reference for body fat measurements in children? Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:457–62. Nichols J, Going S, Loftin M, Stewart D, Nowicki E, Pickrel J. Comparison of two bioelectrical impedance analysis instruments for determining body composition in adolescent girls. Int J Body Compos Res. 2006;4:153–60. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Volgyi E, Tylavsky FA, Lyytikainen A, Suominen H, Alen M, Cheng S. Assessing body composition with DXA and bioimpedance: effects of obesity, physical activity, and age. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:700–5. Chen Z, Wang Z, Lohman T, et al. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry is a valid tool for assessing skeletal muscle mass in older women. J Nutr. 2007;137:2775–80. Neovius M, Hemmingsson E, Freyschuss B, Udden J. Bioelectrical impedance underestimates total and truncal fatness in abdominally obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14:1731–8. Drewnowski A. Obesity and the food environment. Dietary energy density and diet costs. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(3S):154–62. Kant AK, Graubard BI. Energy density of diets reported by American adults: association with food group intake, nutrient intake, and body weight. Int J Obes. 2005;29:950–6. Article CAS Google Scholar Champagne CM, Casey PH, Connell CL, Lower Mississippi Delta Nutrition Intervention Research Initiative, et al. Poverty and food intake in rural America: diet quality is lower in food insecure adults in the Mississippi Delta. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1886–94. Stuff JE, Casey PH, Connell CL, et al. Household food insecurity and obesity, chronic disease, and chronic disease risk factors. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2006;1:43–62. Hoy KM, Goldman JD. Fiber intake of the U.S. population: what we eat in America, NHANES 2009–2010. Food Surveys Research Group, Dietary Data Brief No. 12; 2014. Guenther PM, Casavale KO, Reedy J, et al. Healthy Eating Index 2010. Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. CNPP Fact Sheet No. 2. 2013. http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/sites/default/files/healthy_eating_index/CNPPFactSheetNo2.pdf . Accessed 22 Mar 2016. Suggested Further ReadingBray GA, Bouchard C. Handbook of obesity. Clinical applications. 4th ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2014. Book Google Scholar Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Laboratory methods. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2011-2012/lab_methods_11_12.htm . Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine—FNB. http://www.healthfinder.gov/orgs/HR0139.htm . Mahan LK, Raymond JL, Escott-Stump S, editors. Krause’s food & the nutrition care process. 13th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2011. Schlenker E, Gilbert JA. Williams’ essentials of nutrition & diet therapy. 11th ed. Maryland Heights: Mosby; 2014. USDA, National Agricultural Library, Food and Nutrition Information Center. https://fnic.nal.usda.gov/ . Download references Author informationAuthors and affiliations. Department of Nutritional Epidemiology, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University, 6400 Perkins Road, Baton Rouge, LA, 70808, USA Catherine M. Champagne PhD (RDN, LDN, FADA, FAND, FTOS) Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA George A. Bray M.D. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar Corresponding authorCorrespondence to Catherine M. Champagne PhD (RDN, LDN, FADA, FAND, FTOS) . Editor informationEditors and affiliations. Athabasca University Centre for Science, Athabasca, Alberta, Canada Norman J. Temple Winona State University Department of Biology, Winona, Minnesota, USA Louisiana State University Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA George A. Bray Rights and permissionsReprints and permissions Copyright information© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG About this chapterChampagne, C.M., Bray, G.A. (2017). Nutritional Status: An Overview of Methods for Assessment. In: Temple, N., Wilson, T., Bray, G. (eds) Nutrition Guide for Physicians and Related Healthcare Professionals. Nutrition and Health. Humana Press, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49929-1_35 Download citationDOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49929-1_35 Published : 02 April 2017 Publisher Name : Humana Press, Cham Print ISBN : 978-3-319-49928-4 Online ISBN : 978-3-319-49929-1 eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0) Share this chapterAnyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative Policies and ethics - Find a journal

- Track your research

BRILLIANT DIETITIANS A Registered Dietitian Resource The Dietitian’s Easy Guide To Nutrition Assessment [Free Pdf!]Updated: Feb 23, 2020 As a Registered Dietitian, I have to say that I LOVE doing Nutrition Assessments… Okay, I know not everyone shares my enthusiasm for this sometimes very tedious step of the Nutrition Care Process! Believe it or not, I used to dread the assessment, especially when the Nutrition-Focused Physical Exam (NFPE) became a “thing” for Dietitians. However, now that I really have it down to an organized and simple checklist, I really enjoy doing dietetic assessments! I promise to make this a very comprehensive, yet easy guide! My goal is to help you conduct an excellent nutrition assessment every time, and get really confident in your NFPE’s! Be sure to read on to the end of this post, because I have a totally FREE… Nutrition Assessment Checklist Pdf for you! In this comprehensive guide, you will learn: The Key Components of the Registered Dietitian’s Nutrition Assessment How to Easily Conduct a Patient Assessment of Nutrition Status And…You Will Take Home a FREE Nutrition Assessment Checklist (A Printable Pdf Just For YOU!)  Let’s start with the basics! Nutrition Assessment is the very first step in the Registered Dietitian Nutritionist’s Nutrition Care Process (NCP). The Two Purposes of the Nutrition Assessment: To collect as much data as possible about your patient. To interpret this data to help identify any nutrition-related problems, which leads into the second stage of the NCP, which is Nutrition Diagnosis. The Two Ways That Nutrition Assessment Data Are Collected: A Review Of The Patient’s Medical Records , including medical charts, nursing and physician assessments, and CNA records for food and fluid intake and any other details about feeding. You will want to check the diet order and any listed food allergies at admission (usually in the nurse’s assessment), and even call the dietitian at the previous facility the patient was at to determine the diet, nutritional diagnosis, and any nutrition interventions that may have previously been in place for the patient. A Patient Interview. During the interview, you will ask questions such as: what the patient’s usual body weight is, if there has been a recent weight loss, what the patient likes to eat, if they have been on a special diet order (to their knowledge), what foods they like and dislike, and if they have any food allergies. You will also want to ask about their appetite and if they have been eating less or more than usual. Often, it is helpful or necessary to involve the patient’s family members, especially if the patient is elderly and with any cognitive impairment, or if the patient is a child. Caregivers often provide useful information for your nutrition assessment. The 5 Categories of Nutrition Assessment 😀 One of the reasons I enjoy nutrition assessments is that they are like finding treasure that you can sort into 5 different categories. This is a fun process if you get the hang of it, and the organization of the 5 parameters helps you get all your ducks in a row before moving on to your nutrition diagnosis. 😀 I like to organize this data into an easy chart/checklist format, which, like I promised, I will provide to you for free at the end of this post! First, read on so you understand what a comprehensive assessment entails. For all 5 categories, you will gather information from both the medical records and the patient interview. 😀 TIP: Whenever possible, always review the records before seeing the patient! This will enable you to have a thorough picture of the medical status, diagnoses, medications, and more before you see the patient! Usually, you will already have some ideas in place before you see the patient (such as supplements that might be needed) that you will want to ask the patient about. This can save a lot of time , especially when there is a high RD-to-patient ratio, and you will not have to re-visit patient rooms so often! *Here are your 5 assessment categories: Category 1: Food/Nutrition-Related History Diet Order - written on medical record on nurse’s intake. Check medical records for continuity of previous diet if patient was transferred from another facility. Food Allergies and Intolerances - list any on medical record and verify with patient about food allergies. Food and Nutrient Intake - *ask the patient AND check the CNA records Food and Nutrient Administration - ex. oral, tube feeding, etc. Patient’s Appetite - including recent changes - ask the patient/caregiver Patient’s Usual Diet - ask the patient/caregiver Physical Activity Level - needed for nutrition needs calculation (ex. bed-bound, sedentary, light activity). Category 2: Anthropometric Measurements Current Body Weight (CBW) Body Mass Index (BMI) Ideal Body Weight (IBW) Percent of Ideal Body Weight (%IBW) Recent Weight Change & Weight History : ask patient and check medical records to identify a recent weight loss or gain. Estimated nutrition requirements: Total Calories, Protein needs, Fluid needs. Use Mifflin St Jeor or other appropriate equation with Injury or Activity Factor adjustment. Growth Charts & Percentile Ranks : for children Waist Circumference or Waist-to-Hip ratio/WHR (used in some outpatient or bariatric settings to evaluate as a parameter for metabolic syndrome and obesity-related disease risk) Category 3: Biochemical Data, Medical Tests, and Procedures Blood/Lab work : including electrolytes, blood glucose, lipid testing, visceral proteins. Examine and record findings of any available nutrition-related labs. Imaging : X-rays, MRIs, CT Scans and the related findings. Other testing : gastric emptying study, gallbladder testing, resting metabolic rate etc. Category 4: Nutrition-Focused Physical Findings Nutrition-Focused Physical Exam (NFPE) : includes oral health such as dentures and tooth pain, skin turgor and integrity, loss of subcutaneous fat/muscle mass, etc. Swallowing and Chewing Status - dysphagia, dentition, oral sores, etc. Physical Findings of Vitamin and Mineral Deficiencies Evaluate for Characteristics of Malnutrition : insufficient energy intake, recent weight loss, loss of subcutaneous fat, loss of muscle mass, fluid accumulation that may mask weight loss or be a sign of protein deficiency, diminished functional status, grip strength (if grip strength tools are available). Go to "A Guide to The Nutrition-Focused Physical Exam" to learn more! Category 5: Client History Here you will chart current and past Medical, Surgical, Family, and Social History, with a focus on identifying any nutritionally relevant medical issues. MEDICAL/HEALTH Diagnoses - list all you find on medical record Skin/Wound Status - nurse’s intake - this determines if supplementation may be needed to meet nutritional needs for wound healing (protein, vitamin C, zinc, etc). Recent Surgeries and Procedures - including colonoscopy, orthopedic surgery, etc) Past Medical History, Surgical History, Family Medical History MEDICATIONS Medications and Supplements - usually on medical record on nurse’s intake Allergies - list any on medical record and verify with patient. Note any nutritionally relevant drug side effects like loss of taste, smell, appetite, weight loss/gain, as well as potential drug/nutrient interactions. Any personal/social factors that may affect food intake and availability , such as cognitive capacity, communication or language barriers, income, occupation, education level, use of/eligibility for government programs, motivation level, person responsible for shopping, preparing food at home. FOOD AND NUTRITION Food intake : Dietary recall or food frequency analysis if appropriate setting and time allowance with patient. Knowledge and Beliefs about food; food availability; nutrition quality of life Eating habits and patterns : usual and current appetite, weight history, physical or mental abilities that may affect food intake and self-feeding, typical diet and meal pattern, ethic or religious food preferences. Lifestyle habits and patterns : Alcohol intake, smoking, frequency of dining out, physical activity type/frequency, previous diet education, interest in dietary change, complimentary and alternative medicine use. ARE YOU OVERWHELMED YET? I know, it really looks like a lot! However, I promise you that… Practice makes progress, and progress makes perfect! Over time, going through the assessment steps, you will be surprised at how well it becomes an automatic and easy process for you. In the meantime, I created a *FREE Nutrition Assessment Pdf* just for you! I organize the step sof assessment into actions that make sense. This blog contains the "textbook" description of nutrition assessment, but in practice most RDNs do not take the steps in the order they are written. THAT is why I created this Pdf for you! You can print it and go through the checklist with each patient until you get the hang of it. This is what I WISH I had when I stepped into my dietetic career! And it’s your’s free compliments of Brilliant Dietitians when you subscribe at the bottom of the page. We will deliver it straight to your inbox! Next, be sure to read: "A Guide to The Nutrition-Focused Physical Exam " “ Have a fantastic day and get out there and BE A BRILLIANT DIETITIAN! ” Your Brilliant Dietitian Coach Blog Sources: Width, M. & Reinhard, T. (2018). The Essential Pocket Guide for Clinical Nutrition, 2nd Ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer. - Medical Nutrition Therapy

- Nutrition Care Process

Recent PostsNutrition Interventions and the Nutrition Prescription Nutrition Diagnosis and PES Statements A Guide To The Nutrition Focused Physical Exam  An official website of the United States government The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site. The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely. - Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now . - Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Clin Interv Aging

Assessment and management of nutrition in older people and its importance to healthNutrition is an important element of health in the older population and affects the aging process. The prevalence of malnutrition is increasing in this population and is associated with a decline in: functional status, impaired muscle function, decreased bone mass, immune dysfunction, anemia, reduced cognitive function, poor wound healing, delayed recovery from surgery, higher hospital readmission rates, and mortality. Older people often have reduced appetite and energy expenditure, which, coupled with a decline in biological and physiological functions such as reduced lean body mass, changes in cytokine and hormonal level, and changes in fluid electrolyte regulation, delay gastric emptying and diminish senses of smell and taste. In addition pathologic changes of aging such as chronic diseases and psychological illness all play a role in the complex etiology of malnutrition in older people. Nutritional assessment is important to identify and treat patients at risk, the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool being commonly used in clinical practice. Management requires a holistic approach, and underlying causes such as chronic illness, depression, medication and social isolation must be treated. Patients with physical or cognitive impairment require special care and attention. Oral supplements or enteral feeding should be considered in patients at high risk or in patients unable to meet daily requirements. IntroductionMalnutrition is defined as a state in which a deficiency, excess or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients causes adverse effects on body form, function and clinical outcome. 1 It is more common and increasing in the older population; currently 16% of those >65 years and 2% of those >85 years are classed as malnourished. 2 These figures are predicted to rise dramatically in the next 30 years. Almost two-thirds of general and acute hospital beds are used by people aged >65 years. 3 Studies in developed countries found that up to 15% of community-dwelling and home-bound elderly, 23% to 62% of hospitalized patients and up to 85% of nursing home residents suffer from malnutrition. 4 Malnutrition is associated with a decline in functional status, impaired muscle function, decreased bone mass, immune dysfunction, anemia, reduced cognitive function, poor wound healing, delayed recovering from surgery, higher hospital and readmission rate, and mortality. 5 The etiology is multifactoral and will be discussed at length under several headings - Biological changes of the digestive system with aging

- Physiological changes of the digestive system with aging

- Nutritional assessment in older people

- Pathological and non-pathological weight loss in older people

Biological changes of the digestive systemThere are age-related changes in the gastrointestinal tract. The difficulty is that with age it can be difficult to exclude pathological factors such as diabetes, pancreatitis, liver disease and malignancy, since these factors will have potential adverse effects on the intestine. Selective neurodegeneration of the aging enteric nervous system can lead to gastrointestinal symptoms such as dysphagia, gastrointestinal reflux and constipation. 6 Caloric reduction in rodents can prevent neuronal loss, suggesting that diet may influence the aging gut. 7 Esophageal motility may reduce the reduction of neurons in the mesenteric plexus in older people. 8 Gastric motility is impaired with aging 9 but the small intestine is unaffected. 10 With age colonic motility can be influenced by signal transduction pathways and cellular mechanisms that control smooth muscle contraction which could lead to constipation. 11 Reduced gastric acid secretions have an increasing prevalence with aging. Hypochlorhydia occurs due to chronic gastritis. Consequently, proton pump inhibitors are frequently used for prolonged periods in older people leading to suppressed acid secretions. Procedures such as vagotomy and gastric resections (both seen in older people) cause reduced acid levels. The overall reduction in acid secretions predisposes the gut to small bowel bacterial overgrowth. 12 One study highlighted that 71% of patients on a geriatric ward had bacterial overgrowth of the small intestine and 11% were found to be malnourished. 13 Bacterial overgrowth has been proven to be associated with reduced body weight and reduced intake of micronutrients. 14 Structural changes of the pancreas are seen with aging, but no functional age-related changes are seen with the fluorescein dilaurate test. 15 Secretagogue-stimulated lipase, chymotrypsin and bicarbonate concentration in pancreatic juice have all been shown to decline with aging. 16 Other studies found little evidence of reduced pancreatic secretion with age-independent of factors such as disease and drugs. 17 The liver declines in size and blood flow with age but microscopic changes are subtle. 18 In mice with age it has been shown that changes in the expression of genes in the liver are involved in inflammation, cellular stress and fibrosis. 19 Caloric restriction in mice appeared to reverse age-related changes, indicating that diet influences age-related changes. 20 Changes can occur in the small intestine such as decline in the number of villi and crypts, 18 loss of villi and enterocyte height 21 and decline in mucosal surface. 22 However, there is no clear association between intestinal morphology and nutrient uptake with aging. 23 Physiological changes of digestive system and agingThe anorexia of aging. With increasing age appetite declines and food consumption declines. Healthy older people are less hungry and are fuller before meals, consume smaller meals, eat more slowly, have fewer snacks between meals and become satiated after meals more rapidly after eating a standard meal than younger people. The average daily intake of food decreases by up to 30% between 20 and 80 years. 24 Most of the age-related decrease in energy is a response to the decline in energy expenditure with age. However in many older people the decrease in energy intake is greater than the decrease in energy expenditure, and therefore body weight is lost. This physiological age-related reduction in appetite and energy intake has been termed the “anorexia of aging” ( Figure 1 ). 4  A depiction of the “anorexia of aging”. Abbreviation: GI, gastrointestinal. Changes in body weight and body compositionCross-sectional studies have shown that body weight and body mass index (BMI) increase with age until approximately 50 to 60 years, after which they both decline. 25 A 2-year prospective study showed that community-dwelling American men aged >65 years lost an average of 0.5% of their body weight per year and 13.1% of the group had a weight loss of 4% per year. 26 A prospective cardiovascular health study looked at 4714 home-dwelling subjects > 65 years who did not have cancer. 27 In the 3 years after the study entry 17% had lost 5% or more of their initial body weight. This group were shown to have increased risk-adjusted mortality over the next 4 years compared to the group with stable weight. There is a J shaped curve association with mortality and body weight with increased mortality with low and high BMIs. 28 At a BMI < 22 there is a steady increase in mortality and the combined effect of being underweight and increasing age has a deleterious effect on mortality. 29 With age, body fat increases and fat-free mass decreases because of loss of skeletal muscle, with a loss of up to 3 kg of lean body mass per decade after the age of 50. The mean body fat of a 20-year-old man weighing 80 kg is 15% compared to 29% in 75-year-old man of the same weight. 30 The cause of increase fat is multifactoral: reduced physical activity, reduced growth hormone secretion, diminished sex hormones and decreased resting metabolic rate. The distribution of fat in older people is different from that of younger people. A greater proportion of body fat is intra-hepatic and intra-abdominal, which is associated with insulin resistance 31 and higher risk of ischemic heart disease, stroke and diabetes. Etiology of weight lossThree distinct mechanisms of weight loss in older people have been identified 32 Wasting, an involuntary loss of weight, is mainly due to poor dietary food intake which can be caused by disease and psychological factor causing an overall negative energy balance. Cachexia is an involuntary loss of fat-free mass (muscle, organ, tissue, skin and bone) or body cell mass; it is caused by catabolism and results in changes in body consumption. An acute immune response occurs. Cytokines are released (interleukin [IL]-1, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alfa [TNFα]) that have profound effects on hormone production and metabolism causing increased resting energy expenditure. 33 Amino acids from muscle to the liver, an increase in gluconeogenesis and a shift of albumin production to acute phase proteins causes nitrogen balance to become negative, so muscle mass is lost. Cachexia is seen in many chronic diseases such as heart failure and rheumatoid arthritis. It is also seen in malignancy. The major age-related physiological change in older people is a decline in skeletal muscle mass, known as sarcopenia. 34 Reduced physical activity has a crucial role since lack of exercise causes muscle disease and, with time, muscle loss. However, lack of exercise is not the only cause and it is thought that hormonal, neural and cytokine activities play a role. 32 Increased cytokine activity increases levels of acute phase proteins which break down muscle. Levels of sex hormones, glucocorticoids and catecholamines decline in older people which in turn increase pro-inflammatory cytokines. The central nervous system can play a part in sarcopenia. Neurones lost from the spinal cord will lead to loss of muscle. 35 Also the remaining neurones adopt muscle fibers and control larger units of muscle cells causing the units to become less efficient, which leads to weakness. Stroke and neural disease cause neurone cell death and result in muscle atrophy. Physiological anorexiaCauses of physiological anorexia are not fully understood, but the following are thought to contribute: - Diminished sense of smell and taste

- Increased cytokine activity

- Delayed gastric emptying

- Altered gastric distension

Taste and smell make food enjoyable. The sense of taste and smell deteriorate with age. In one study more than 60% of subjects 65 to 80 years and more than 80% of subjects aged >80 years had developed a reduced sense of smell and taste compared to less than 10% of those <50 years old. 36 The decline in sense of smell decreases food intake in older people and can influence the type of food eaten, and it has been shown that a reduced sense of smell is associated with reduced interest in and intake of food. Also, older patients with a reduced sense of taste tend to have a less varied diet and consequently develop micronutrient deficiencies. The loss of sense of taste is not understood fully but may be caused by a reduced number of taste buds. 37 Modifications in the olfactory epithelium, receptors and neural pathways may affect sense of smell. Drugs such as Parkinson’s medications and antidepressants affect sense of taste. Studies have shown that improving flavor of foods can improve nutritional intake and body weight in nursing-home patients. 38 The role of cytokines has been discussed earlier. Circulating levels of IL1, IL6 and TNFα have been shown to be higher in older people and associated with reduced muscle mass. Older people commonly complain of increased fullness and early satiation during a meal which may be caused by changes in gastrointestinal sensory function, as with age there is reduced sensitivity to gastrointestinal distension. Aging is associated with impairment of receptive relaxation of the gastric fundus, causing rapid antral filling and distension and earlier satiety. 39 In a study in which young and old men were underfed by approximately 750 kcal/day for 21 days, both groups of men lost weight. 40 After the underfeeding period the men were allowed to eat freely. The young men ate more than at baseline and quickly returned to their normal weight, whereas the older men did not compensate and returned to their baseline intake and did not regain weight. The combination of age-related physiological anorexia and impaired homeostasis means older people do not respond to acute undernutrition compared with young men. The hypothalamus controls hunger and satiety. The nucleus arcuatus has neurones that release neuropeptide Y (NPY), an agouti-related peptide, which mediates hunger and inhibit satiety. 41 Pro-opiomelacortin, which is produced in the nucleus arcuatus, stimulates satiety. 41 Peripheral hormones affect the hypothalamus hunger–satiety control regulation. Cholecystokinin (CCK) is released in the proximal bowel and is the protype satiety hormone. It is released in the response to nutrients from the antrum, particularly lipids and proteins. 42 It has been shown to be increased in older people and correlated with high levels of satiety and low hunger. 43 Pancreatic polypeptide (PPY) is released by the distal intestine in the presence of nutrients in the lumen. 44 PPY inhibits NPY and causes satiety. Both CCK and PPY are enteric peptides involved in gastrointestinal motility in response to eating. 45 High levels of fasting and postprandial CCK and PPY may cause prolonged satiety by slowing antral emptying. Leptin is a hormone produced by adipose cells whose main role is maintaining energy balance. Low leptin signals loss of body fat and a need for energy intake, while high leptin level implies adequate body fat and no need for further food intake. 41 Older people tend to have higher levels of leptin. 46 Insulin regulates glucose metabolism. It is a satiety hormone that works by enhancing the leptin signal to the hypothalamus and inhibiting gherlin, the only peripheral hormone known to stimulate appetite. 47 It is produced and secreted in the endocrine mucosa to enhance food intake. Aging is associated with reduced glucose tolerance and elevated insulin levels, which may amplify the leptin signal 48 and inhibit ghrelin. 49 Nutritional assessmentDietary assessment. Quantifying nutritional intake is best preformed by a dietitian. Different methods can be used. Twenty-four hour recall is commonly used and is based on an interview during which the patient recalls all food consumed in the previous 24 hours. 50 The main disadvantages are that it represents only food intake for 1 day and may not represent a patient’s typical intake. Data can also be affected if the patient has cognitive impairment. Food records for 7 days for all food and drink consumed can be used and help eliminate day-to-day variations. A food frequency multiquestion questionnaire is used to explore dietary intake over a period of time. 51 This is more suitable for evaluation of groups rather than individuals. Unintentional weight loss is one of the best predictors of worst clinical outcome and in older people is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. 52 Clinical assessmentA large number of clinical signs indicate nutritional deficiencies. The general impression is a wasted, thin individual with dry scaly skin and poor wound healing. The hair is thin and nails are spooned and depigmented. Patients complain of bone and joint pain and edema. Specific nutritional deficiencies are associated with specific clinical signs (see Table 1 ). Clinical signs and nutritional deficiencies | | | |

|---|

| Skin | Dry scaly skin | Zinc/essential fatty acids | | Follicular hyperkeratosis | Vitamin A, C | | Petechiae | Vitamin C, K | | Photosensitive dermatitis | Niacin | | Poor wound healing | Zinc, vitamin C | | Scrotal dermatitis | Riboflavin | | Hair | Thin/depigmented | Protein | | Easy pluckability | Protein, zinc | | Nail | Transverse depigmentation | Albumin | | Spooned | Iron | | Eyes | Night blindness | Vitamin A, zinc | | Conjunctival inflammation | Riboflavin | | Keratomalacia | Vitamin A | | Mouth | Bleeding gums | Vitamin C, riboflavin | | Glositis | Niacin, piridoxin, riboflavin | | Atrophic papillae | Iron | | Hypogeusia | Zinc, vitamin A | | Neck | Thyroid enlargement | Iodine | | Parotid enlargement | Protein | | Abdomen | Diarrhea | Niacin, folate, vitamin B12 | | Hepatomegaly | Protein | | Extremities | Bone tenderness | Vitamin D | | Joint pain | Vitamin C | | Muscle tenderness | Thiamine | | Muscle wasting | Protein, selenium vitamin D | | Edema | Protein | | Neurological | Ataxia | Vitamin B12 | | Tetany | Calcium, magnesium | | Parasthesia | Thiamine, vitamin B12 | | Ataxia | Vitamin B12 | | Dementia | Vitamin B12, niacin | | Hyporeflexia | Thiamine |