Malthusian Theory of Population: Explained with its Criticism

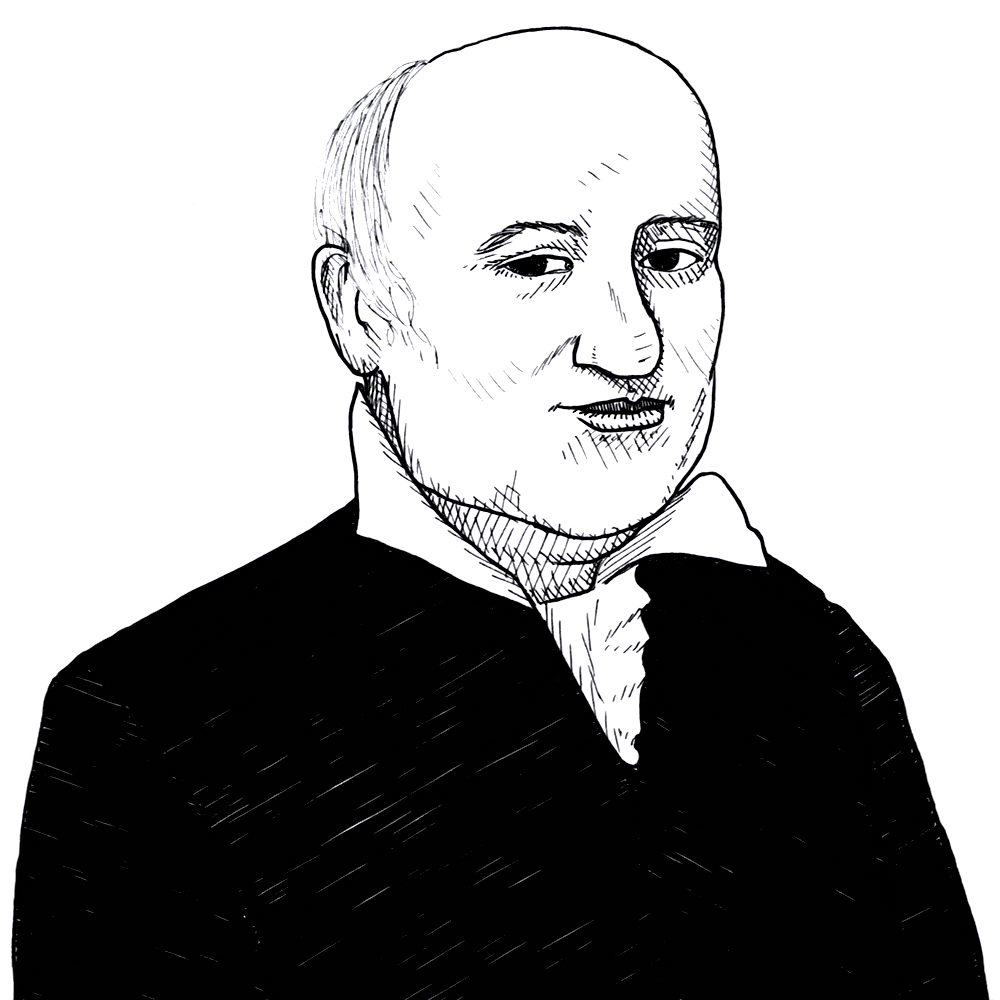

The most well-known theory of population is the Malthusian theory. Thomas Robert Malthus wrote his essay on “Principle of Population” in 1798 and modified some of his conclusions in the next edition in 1803.

The rapidly increasing population of England encouraged by a misguided Poor Law distressed him very deeply.

He feared that England was heading for a disaster, and he considered it his solemn duty to warn his country-men of impending disaster. He deplored “the strange contrast between over-care in breeding animals and carelessness in breeding men.”

His theory is very simple. To use his own words: “By nature human food increases in a slow arithmetical ratio; man himself increases in a quick geometrical ratio unless want and vice stop him.The increase in numbers is necessarily limited by the means of subsistence Population invariably increases when the means of subsistence increase, unless prevented by powerful and obvious checks.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Malthus based his reasoning on the biological fact that every living organism tends to multiply to an unimaginable extent. A single pair of thrushes would multiply into 19,500,000 after the life of the first pair and 20 years later to 1,200,000,000,000,000,000,000 and if they stood shoulder to shoulder about one m every 150,000 would be able to find a perching space on the whole surface of the globe! According to Huxley’s estimate, the descendants of a single greenfly, if all survived and multiplied, would, at the end of one summer, weigh down the population of China! Human beings are supposed to double every 25 years and a coup/e can increase to the size of the present population in 1,750 years!

Such is the prolific nature of every specie. The power of procreation is inherent and insistent, and must find expression. Cantillon says, “Men multiply like mice in a barn.” Production of food, on the other hand, is subject to the law of diminishing returns. On the basis of these two premises, Malthus concluded that population tended to outstrip the food supply. If preventive checks, like avoidance of marriage, later marriage or less children per marriage, are not exercised, then positive checks, like war, famine and disease, will operate.

The theory propounded by Malthus can be summed up in the following propositions:

(1) Food is necessary to the life of man and, therefore, exercises a strong check on population. In other words, population is necessarily limited by the means of subsistence (i.e., food).

(2) Population increases faster than food production. Whereas population increases in geometric progression, food production increases in arithmetic progression.

(3) Population always increases when the means of subsistence increase, unless prevented by some powerful checks.

(4) There are two types of checks which can keep population on a level with the means of subsistence. They are the preventive and a positive check.

The first proposition is that the population of a country is limited by the means of subsistence. In other words, the size of population is determined by the availability of food. The greater the food production, the greater the size of the population which can be sustained. The check of deaths caused by want of food and poverty would limit the maximum possible population.

The second proposition states that the growth of population will out-run the increase in food production. Malthus thought that man’s sexual urge to bear offspring knows no bounds. He seemed to think that there was no limit to the fertility of man. But the power of land to produce food is limited. Malthus thought that the law of diminishing returns operated in the field of agriculture and that the operation of this law prevented food production from increasing in proportion to labour and capital invested in land.

In fact, Malthus observed that population would tend to increase at a geometric rate (2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, etc.), but food supply would tend to increase at an arithmetic rate (2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12). Thus, at the end of two hundred years “population would be to the means of subsistence as 259 to 9; in three centuries as 4,096 to 13, and in two thousand years the difference would be incalculable.” Therefore, Malthus asserted that population would ultimately outstrip food supply.

According to the third proposition, as the food supply in a country increases, the people will produce more children and would have larger families. This would increase the demand for food and food per person will again diminish. Therefore, according to Malthus, the standard of living of the people cannot rise permanently. As regards the fourth proposition, Malthus pointed out that there were two possible checks which could limit’ the growth of population: (a) Preventive checks, and (b) Positive checks.

Preventive Checks:

Preventive checks exercise their influence on the growth of population by bringing down the birth rate. Preventive checks are those checks which are applied by man. Preventive checks arise from man’s fore-sight which enables him to see distant consequences He sees the distress which frequently visits those who have large families.

He thinks that with a large number of children, the standard of living of the family is bound to be lowered. He may think that if he has to support a large family, he will have to subject himself to greater hardships and more strenuous labour than that in his present state. He may not be able to give proper education to his children if they are more in number.

Further, he may not like exposing his children to poverty or charity by his inability to provide for them. These considerations may force man to limit his family. Late marriage and self-restraint during married life are the examples of preventive checks applied by man to limit the family.

Positive Checks:

Positive checks exercise their influence on the growth of population by increasing the death rate. They are applied by nature. The positive checks to population are various and include every cause, whether arising from vice or misery, which in any degree contributes to shorten the natural duration of human life.

The unwholesome occupations, hard labour, exposure to the seasons, extreme poverty, bad nursing of children, common diseases, wars, plagues and famines ire some of the examples of positive checks. They all shorten human life and increase the death rate.

Malthus recommended the use of preventive checks if mankind was to escape from the impending misery. If preventive checks were not effectively used, positive checks like diseases, wars and famines would come into operation. As a result, the population would be reduced to the level which can be sustained by the available quantity of food supply.

Criticism of Malthusian Theory:

The Malthusian theory of population has been a subject of keen controversy.

The following are some of the grounds on which it has been criticized:

(i) It is pointed out that Malthus’s pessimistic conclusions have not been borne out by the history of Western European countries. Gloomy forecast made by Malthus about the economic conditions of future generations of mankind has been falsified in the Western world. Population has not increased as rapidly as predicted by Malthus; on the other hand, production has increased tremendously because of the rapid advances in technology. As a result, living standards of the people have risen instead of falling as was predicted by Malthus.

(ii) Malthus asserted that food production would not keep pace with population growth owing to the operation of the law of diminishing returns in agriculture. But by making rapid advances in technology and accumulating capital in larger quantity, advanced countries have been able to postpone the stage of diminishing returns. By making use of fertilizers, pesticide better seeds, tractors and other agricultural machinery, they have been able to increase their production greatly.

In fact, in most of the advanced countries the rate of increase of food production has been much greater than the rate of population growth. Even in India now, thanks to the Green Revolution, the increase in food production is greater than the increase in population. Thus, inventions and improvements in the methods of production have belied the gloomy forecast of Malthus by holding the law of diminishing returns in check almost indefinitely.

(iii) Malthus compared the population growth with the increase in food production alone. Malthus held that because land was available in limited quantity, food production could not rise faster than population. But he should have considered all types of production in considering the question of optimum size of population. England did feel the shortage of land and food.

If England had been forced to support her population entirely from her own soil, there can be little doubt that England would have experienced a series of famines by which her growth of population would have been checked.But England did not experience such a disaster. It is because England industrialized itself by developing her natural resources other than land like coal and iron, and accumulating man-made capital equipment like factories, tools, machinery, mines, ships and railways, this enabled her to produce plenty of industrial and manufacturing goods which she then exported in exchange for food-stuffs from foreign countries.

There is no food problem in Great Britain. Therefore, Malthus made a mistake in taking agricultural land and food production alone into account when discussing the population question. As already said, he should have rather considered all types of production.

(iv) Malthus held that the increase in the means of subsistence or food supplies would cause population to grow rapidly so that ultimately means of subsistence or food supply would be in level with population, and everyone would get only bare minimum subsistence. In other words, according to Malthus, living standards of the people cannot rise in the long run above the level of minimum subsistence. But, as already pointed out, living standards of the people in the Western world have risen greatly and stand much above the minimum subsistence level.

There is no evidence of birth-rate rising with the increases in the standard of living. Instead, there is evidence that birth-rates fall as the economy grows. In Western countries, attitude towards children changed as they developed economically. Parents began to feel that it was their duty to do as much as they could for each child.

Therefore, they preferred not to have more children than they could attend to properly. People now began to care more for maintaining a higher standard of living rather than for bearing more children. The wide use of contraceptives in the Western world brought down the birth rates. This change in the attitude towards children and the wide use of contraceptives in the Western world has falsified Malthusian doctrine.

(v) Malthus gave no proof of his assertion that population increased exactly in geometric progression and food production increased exactly in arithmetic progression. It has been rightly pointed out that population and food supply do not change in accordance with these mathematical series. Growth of population and food supply cannot be expected to show the precision or accuracy of such series.

However, Malthus, in later editions of his book, did not insist on these mathematical terms and only held that there was an inherent tendency in population to outrun the means of subsistence. We have seen above that even this is far from true.

There is no doubt that the civilized world has kept the population in check. It is, however, to be regretted that population has been increasing at the wrong end. The poor people, who can ill-afford to bring up and educate children, are multiplying, whereas the rich are applying breaks on the increase of the size of their families.

Is Malthusian Theory Valid Today?

We must, however, add that though the gloomy conclusions of Malthus have not turned out to be true due to several factors which have made their appearance only in recent times, yet the essentials of the theory have not been demolished. He said that unless preventive checks were exercised, positive checks would operate. This is true even today. The Malthusian theory fully applies in India.

We are at present in that unenviable position which Malthus feared. We have the highest birth-rate and the highest death-rate in the world. Grinding poverty, ever-recurring epidemics, famine and communal quarrels are the order of the day. We are deficient in food supply.

Our standard of living is incredibly low. Who can say that Malthus was not a true prophet, if not for his country, at any rate for the Asiatic countries like India, Pakistan and China? No wonder that intense family planning drive is on in India at present.

Related Articles:

- The Malthusian Theory of Population (Criticism)

- Malthusian Theory of Population (With Diagram)

- Malthusian Theory of Population (With Criticisms) | Economics

- Malthusian Theory and the Optimum Theory | Population

An Essay on the Principle of Population [1798, 1st ed.]

- Thomas Robert Malthus (author)

This is the first edition of Malthus’s Essay on the Principle of Population. In this work Malthus argues that there is a disparity between the rate of growth of population (which increases geometrically) and the rate of growth of agriculture (which increases only arithmetically). He then explores how populations have historically been kept in check.

- EBook PDF This text-based PDF or EBook was created from the HTML version of this book and is part of the Portable Library of Liberty.

- ePub ePub standard file for your iPad or any e-reader compatible with that format

- Kindle This is an E-book formatted for Amazon Kindle devices.

An Essay on the Principle of Population, as it affects the future Improvement of Society, with Remarks on the Speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet, and Other Writers (London: J. Johnson 1798). 1st edition.

The text is in the public domain.

- Economic theory. Demography

Related Collections:

- Malthus: For and Against

Related People

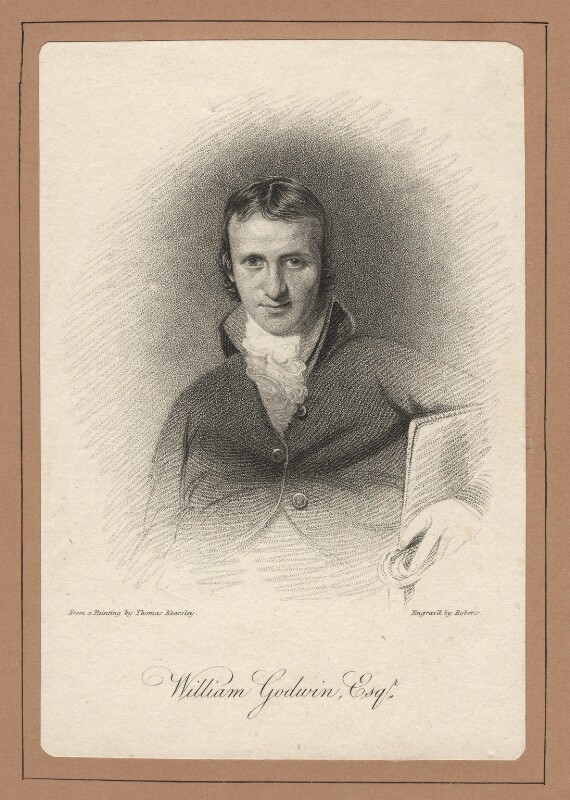

William Godwin (1757-1836) was an English radical political philosopher and novelist. He wrote an important critique of Malthus' theory on population.

David Ricardo followed in the footsteps of Adam Smith. Known for the concept of comparative advantage, he was able to demonstrate the weaknesses of Malthus' theory of population.

With Malthus, Say was also a member of the second phase of the classical political economists. The classical school developed free market economics into a consistent, scientific body of knowledge which quickly became the economic orthodoxy in the first half of the 19th century. Its members were very influential in reforming British government policy especially in the areas of free trade and economic deregulation.

Another member of the second wave of classical economists.

Critical Responses

William Godwin

A lengthy and belated reply to Malthus by the radical individualist Godwin. Whereas Malthus took a pessimistic view of the pressures of population growth, Godwin was more optimistic about the capacity of people to limit the growth of their families.

Connected Readings

Econlib Article

Morgan Rose

Thomas Robert Malthus is arguably the most maligned economist in history. For over two hundred years, since the first publication of his book An Essay on the Principle of Population, Malthus’ work has been misunderstood and misrepresented, and severe, alarming predictions have been attached to his…

Malthus had no objection to the idea that wealth derived from manufacturing production could, subject to certain hindrances, be exchanged to increase the amount of food available. He seems only to have misjudged the degree to which those hindrances would be reduced over time. He did not recognize…

What to read next.

Ross Emmett

While many liberty-loving economists are happy to correct the criticisms of Smith, many are equally happy to criticize Malthus for the Malthusian trap, not realizing that the usual portrayal of Malthus is equally false. Malthus shares far more with Smith than most expect. He is, in many ways, as…

- Project Gutenberg

- 74,754 free eBooks

- 6 by T. R. Malthus

An Essay on the Principle of Population by T. R. Malthus

Read now or download (free!)

Similar books, about this ebook.

- Privacy policy

- About Project Gutenberg

- Terms of Use

- Contact Information

- Liberty Fund

- Adam Smith Works

- Law & Liberty

- Browse by Author

- Browse by Topic

- Browse by Date

- Search EconLog

- Latest Episodes

- Browse by Guest

- Browse by Category

- Browse Extras

- Search EconTalk

- Latest Articles

- Liberty Classics

- Search Articles

- Books by Date

- Books by Author

- Search Books

- Browse by Title

- Biographies

- Search Encyclopedia

- #ECONLIBREADS

- College Topics

- High School Topics

- Subscribe to QuickPicks

- Search Guides

- Search Videos

- Library of Law & Liberty

- Home /

ECONLIB Books

An Essay on the Principle of Population

By thomas robert malthus.

There are two versions of Thomas Robert Malthus’s Essay on the Principle of Population . The first, published anonymously in 1798, was so successful that Malthus soon elaborated on it under his real name. * The rewrite, culminating in the sixth edition of 1826, was a scholarly expansion and generalization of the first.Following his success with his work on population, Malthus published often from his economics position on the faculty at the East India College at Haileybury. He was not only respected in his time by contemporaneous intellectuals for his clarity of thought and willingness to focus on the evidence at hand, but he was also an engaging writer capable of presenting logical and mathematical concepts succinctly and clearly. In addition to writing principles texts and articles on timely topics such as the corn laws, he wrote in many venues summarizing his initial works on population, including a summary essay in the Encyclopædia Britannica on population.The first and sixth editions are presented on Econlib in full. Minor corrections of punctuation, obvious spelling errors, and some footnote clarifications are the only substantive changes. * Malthus’s “real name” may have been Thomas Robert Malthus, but a descendent, Nigel Malthus, reports that his family says he did not use the name Thomas and was known to friends and colleagues as Bob. See The Malthus Homepage, a site maintained by Nigel Malthus, a descendent.For more information on Malthus’s life and works, see New School Profiles: Thomas Robert Malthus and The International Society of Malthus. Lauren Landsburg

Editor, Library of Economics and Liberty

First Pub. Date

London: John Murray

6th edition

The text of this edition is in the public domain. Picture of Malthus courtesy of The Warren J. Samuels Portrait Collection at Duke University.

Table of Contents

- Chapter III

- Chapter VII

- Chapter VIII

- Chapter XII

- Chapter XIII

- Chapter XIV

- Bk.II,Ch.II

- Bk.II,Ch.III

- Bk.II,Ch.IV

- Bk.II,Ch.VI

- Bk.II,Ch.VII

- Bk.II,Ch.VIII

- Bk.II,Ch.IX

- Bk.II,Ch.XI, On the Fruitfulness of Marriages

- Bk.II,Ch.XII

- Bk.II,Ch.XIII

- Bk.III,Ch.I

- Bk.III,Ch.II

- Bk.III,Ch.III

- Bk.III,Ch.IV

- Bk.III,Ch.V

- Bk.III,Ch.VI

- Bk.III,Ch.VII

- Bk.III,Ch.VIII

- Bk.III,Ch.IX

- Bk.III,Ch.X

- Bk.III,Ch.XI

- Bk.III,Ch.XII

- Bk.III,Ch.XIII

- Bk.III,Ch.XIV

- Bk.IV,Ch.II

- Bk.IV,Ch.III

- Bk.IV,Ch.IV

- Bk.IV,Ch.VI

- Bk.IV,Ch.VII

- Bk.IV,Ch.VIII

- Bk.IV,Ch.IX

- Bk.IV,Ch.XI

- Bk.IV,Ch.XII

- Bk.IV,Ch.XIII

- Bk.IV,Ch.XIV

- Appendix II

Preface to the Second Edition

The Essay on the Principle of Population, which I published in 1798, was suggested, as is expressed in the preface, by a paper in Mr. Godwin’s Inquirer. It was written on the impulse of the occasion, and from the few materials which were then within my reach in a country situation. The only authors from whose writings I had deduced the principle, which formed the main argument of the Essay, were Hume, Wallace, Adam Smith, and Dr. Price; and my object was to apply it, to try the truth of those speculations on the perfectibility of man and society, which at that time excited a considerable portion of the public attention.

In the course of the discussion I was naturally led into some examination of the effects of this principle on the existing state of society. It appeared to account for much of that poverty and misery observable among the lower classes of people in every nation, and for those reiterated failures in the efforts of the higher classes to relieve them. The more I considered the subject in this point of view, the more importance it seemed to acquire; and this consideration, joined to the degree of public attention which the Essay excited, determined me to turn my leisure reading towards an historical examination of the effects of the principle of population on the past and present state of society; that, by illustrating the subject more generally, and drawing those inferences from it, in application to the actual state of things, which experience seemed to warrant, I might give it a more practical and permanent interest.

In the course of this inquiry I found that much more had been done than I had been aware of, when I first published the Essay. The poverty and misery arising from a too rapid increase of population had been distinctly seen, and the most violent remedies proposed, so long ago as the times of Plato and Aristotle. And of late years the subject has been treated in such a manner by some of the French Economists; occasionally by Montesquieu, and, among our own writers, by Dr. Franklin, Sir James Stewart, Mr. Arthur Young, and Mr. Townsend, as to create a natural surprise that it had not excited more of the public attention.

Much, however, remained yet to be done. Independently of the comparison between the increase of population and food, which had not perhaps been stated with sufficient force and precision, some of the most curious and interesting parts of the subject had been either wholly omitted or treated very slightly. Though it had been stated distinctly, that population must always be kept down to the level of the means of subsistence; yet few inquiries had been made into the various modes by which this level is effected; and the principle had never been sufficiently pursued to its consequences, nor had those practical inferences drawn from it, which a strict examination of its effects on society appears to suggest.

These therefore are the points which I have treated most in detail in the following Essay. In its present shape it may be considered as a new work, and I should probably have published it as such, omitting the few parts of the former which I have retained, but that I wished it to form a whole of itself, and not to need a continual reference to the other. On this account I trust that no apology is necessary to the purchasers of the first edition.

To those who either understood the subject before, or saw it distinctly on the perusal of the first edition, I am fearful that I shall appear to have treated some parts of it too much in detail, and to have been guilty of unnecessary repetitions. These faults have arisen partly from want of skill, and partly from intention. In drawing similar inferences from the state of society in a number of different countries, I found it very difficult to avoid some repetitions; and in those parts of the inquiry which led to conclusions different from our usual habits of thinking, it appeared to me that, with the slightest hope of producing conviction, it was necessary to present them to the reader’s mind at different times, and on different occasions. I was willing to sacrifice all pretensions to merit of composition, to the chance of making an impression on a larger class of readers.

The main principle advanced is so incontrovertible, that, if I had confined myself merely to general views, I could have intrenched myself in an impregnable fortress; and the work, in this form, would probably have had a much more masterly air. But such general views, though they may advance the cause of abstract truth, rarely tend to promote any practical good; and I thought that I should not do justice to the subject, and bring it fairly under discussion, if I refused to consider any of the consequences which appeared necessarily to flow from it, whatever these consequences might be. By pursuing this plan, however, I am aware that I have opened a door to many objections, and, probably, to much severity of criticism: but I console myself with the refection, that even the errors into which I may have fallen, by affording a handle to argument, and an additional excitement to examination, may be subservient to the important end of bringing a subject so nearly connected with the happiness of society into more general notice.

Throughout the whole of the present work I have so far differed in principle from the former, as to suppose the action of another check to population which does not come under the head either of vice or misery; and, in the latter part I have endeavoured to soften some of the harshest conclusions of the first Essay. In doing this, I hope that I have not violated the principles of just reasoning; nor expressed any opinion respecting the probable improvement of society, in which I am not borne out by the experience of the past. To those who still think that any check to population whatever would be worse than the evils which it would relieve, the conclusions of the former Essay will remain in full force; and if we adopt this opinion we shall be compelled to acknowledge, that the poverty and misery which prevail among the lower classes of society are absolutely irremediable.

I have taken as much pains as I could to avoid any errors in the facts and calculations which have been produced in the course of the work. Should any of them nevertheless turn out to be false, the reader will see that they will not materially affect the general scope of the reasoning.

From the crowd of materials which presented themselves, in illustration of the first branch of the subject, I dare not flatter myself that I have selected the best, or arranged them in the most perspicuous method. To those who take an interest in moral and political questions, I hope that the novelty and importance of the subject will compensate the imperfections of its execution.

Preface to the Fifth Edition

This Essay was first published at a period of extensive warfare, combined, from peculiar circumstances, with a most prosperous foreign commerce.

It came before the public, therefore, at a time when there would be an extraordinary demand for men, and very little disposition to suppose the possibility of any evil arising from the redundancy of population. Its success, under these disadvantages, was greater than could have been reasonably expected; and it may be presumed that it will not lose its interest, after a period of a different description has succeeded, which has in the most marked manner illustrated its principles, and confirmed its conclusions.

On account, therefore, of the nature of the subject, which, it must be allowed is one of permanent interest, as well as of the attention likely to be directed to it in future, I am bound to correct those errors of my work, of which subsequent experience and information may have convinced me, and to make such additions and alterations as appear calculated to improve it, and promote its utility.

It would have been easy to have added many further historical illustrations of the first part of the subject; but as I was unable to supply the want I once alluded to, of accounts of sufficient accuracy to ascertain what part of the natural power of increase each particular check destroys, it appeared to me that the conclusion which I had before drawn from very ample evidence of the only kind that could be obtained, would hardly receive much additional force by the accumulation of more, precisely of the same description.

In the two first books, therefore, the only additions are a new chapter on France, and one on England, chiefly in reference to facts which have occurred since the publication of the last edition.

In the third book I have given an additional chapter on the Poor-Laws; and as it appeared to me that the chapters on the Agricultural and Commercial Systems, and the Effects of increasing Wealth on the Poor, were not either so well arranged, or so immediately applicable to the main subject, as they ought to be; and as I further wished to make some alterations in the chapter on Bounties upon Exportation, and add something on the subject of Restrictions upon Importation, I have recast and rewritten the chapters which stand the 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th, 12th, 13th, in the present edition; and given a new title, and added two or three passages, to the 14th and last chapter of the same book.

In the fourth book I have added a new chapter to the one entitled Effects of the Knowledge of the principal Cause of Poverty on Civil Liberty; and another to the chapter on the Different Plans of improving the Poor; and I have made a considerable addition to the Appendix, in reply to some writers on the Principles of Population, whose works have appeared since the last edition.

These are the principal additions and alterations made in the present edition. They consist, in a considerable degree, of the application of the general principles of the Essay to the present state of things.

For the accommodation of the purchasers of the former editions, these additions and alterations will be published in a separate volume.

Book I, Chapter II.

In my review of the different stages of society, I have been accused of not allowing sufficient weight in the prevention of population to moral restraint; but when the confined sense of the term, which I have here explained, is adverted to, I am fearful that I shall not be found to have erred much in this respect. I should be very glad to believe myself mistaken.

It should be observed, that, by an increase in the means of subsistence, is here meant such an increase as will enable the mass of the society to command more food. An increase might certainly take place, which in the actual state of a particular society would not be distributed to the lower classes, and consequently would give no stimulus to population.

Book I, Chapter III.

On The Site

- Rethinking the Western Tradition

- business & economics

An Essay on the Principle of Population

The 1803 Edition

by Thomas Robert Malthus

Edited by Shannon C. Stimson

Series: Rethinking the Western Tradition

624 Pages , 5.50 x 8.25 x 1.25 in , 2 b-w illus.

- 9780300177411

- Published: Tuesday, 13 Feb 2018

- 9780300231892

Also Available At:

- Barnes & Noble

- Seminary Co-op

- Description

Thomas Robert Malthus (1766–1834) was an English cleric and scholar. Shannon C. Stimson holds the Leavey Chair in the Foundations of American Freedom at Georgetown University. Her books include After Adam Smith: A Century of Transformation in Politics and Political Economy , Ricardian Politics , both with Murray Milgate, and The American Revolution in the Law .

“This affordable version represents significant added value, not only by providing a crisp readable text, but by its inclusion of five interpretive essays.”—Choice “This new edition fills a real gap and makes available a text of pivotal significance in nineteenth and twentieth century intellectual history. The ancillary essays make this a very useful edition for students and scholars alike.”—Robert Mayhew, author of Malthus: The Life and Legacies of an Untimely Prophet

Related Books

Sign up for updates on new releases and special offers

Newsletter signup, shipping location.

Our website offers shipping to the United States and Canada only. For customers in other countries:

Mexico and South America: Contact W.W. Norton to place your order. All Others: Visit our Yale University Press London website to place your order.

Shipping Updated

Learn more about Schreiben lernen, 2nd Edition, available now.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The book An Essay on the Principle of Population was first published anonymously in 1798, [1] but the author was soon identified as Thomas Robert Malthus.The book warned of future difficulties, on an interpretation of the population increasing in geometric progression (so as to double every 25 years) [2] while food production increased in an arithmetic progression, which would leave a ...

%PDF-1.2 %âãÏÓ 824 0 obj /Linearized 1 /O 826 /H [ 718 722 ] /L 948754 /E 4957 /N 134 /T 932155 >> endobj xref 824 13 0000000016 00000 n 0000000611 00000 n 0000001440 00000 n 0000001616 00000 n 0000001746 00000 n 0000001854 00000 n 0000003421 00000 n 0000004448 00000 n 0000004470 00000 n 0000004580 00000 n 0000004689 00000 n 0000000718 00000 n 0000001418 00000 n trailer /Size 837 /Info 823 ...

The most well-known theory of population is the Malthusian theory. Thomas Robert Malthus wrote his essay on "Principle of Population" in 1798 and modified some of his conclusions in the next edition in 1803. The rapidly increasing population of England encouraged by a misguided Poor Law distressed him very deeply. He feared that England was heading for a disaster, and he considered it his ...

This is the first edition of Malthus's Essay on the Principle of Population. In this work Malthus argues that there is a disparity between the rate of growth of population (which increases geometrically) and the rate of growth of agriculture (which increases only arithmetically). He then explores how populations have historically been kept in check.

In Thomas Malthus: Malthusian theory …anonymously the first edition of An Essay on the Principle of Population as It Affects the Future Improvement of Society, with Remarks on the Speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet, and Other Writers.The work received wide notice. Briefly, crudely, yet strikingly, Malthus argued that infinite human hopes for social…

"An Essay on the Principle of Population" by Thomas R. Malthus is a scientific publication written in the late 18th century. The essay explores the dynamics between population growth and subsistence, positing that population tends to increase at a geometric rate, while food production can only increase arithmetically, leading to inevitable ...

An Essay on the Principle of Population by Thomas Robert Malthus (1798) is a book widely viewed as having profound impact on the biological and social sciences by recognizing basic biophysical ...

978--521-41954-3 - T. R. Malthus: An Essay on the Principle of Population Donald Winch Frontmatter More information. Introduction entire career as an author and teacher, made its initial appearance as an anonymous pamphlet. It was the first published work of a mild-

There are two versions of Thomas Robert Malthus's Essay on the Principle of Population. The first, published anonymously in 1798, was so successful that Malthus soon elaborated on it under his real name. * The rewrite, culminating in the sixth edition of 1826, was a scholarly expansion and generalization of the first.Following his success with […]

An Essay on the Principle of Population The 1803 Edition. by Thomas Robert Malthus. Edited by Shannon C. Stimson. Series: Rethinking the Western Tradition. 624 Pages, 5.50 x 8.25 x 1.25 in, 2 b-w illus. Paperback; 9780300177411; Published: Tuesday, 13 Feb 2018; $20.00. BUY . eBook;