An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

What Type of Communication during Conflict is Beneficial for Intimate Relationships?

Nickola c overall, james k mcnulty.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding Author: Nickola C. Overall, School of Psychology, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand. [email protected]

What constitutes effective communication during conflict? Answering this question requires (a) clarifying whether communication expresses opposition versus cooperation and is direct versus indirect, (b) assessing the mechanisms through which communication effects relationships, and (c) identifying the contextual factors that determine the impact of communication. Recent research incorporating these components illustrates that direct opposition is beneficial when serious problems need to be addressed and partners are able to change, but can be harmful when partners are not confident or secure enough to be responsive. In contrast, cooperative communication involving affection and validation can be harmful when serious problems need to changed, but may be beneficial when problems are minor, cannot be changed, or involve partners whose defensiveness curtails problem solving.

Keywords: relationship conflict, communication, conflict behavior, problem resolution, context

Stress can arise in relationships when partners experience conflicting goals, motives and preferences. Common sources of conflict involve unmet expectations, intimacy, time spent together, financial difficulties, discrepancies in equity and power, domestic and family responsibilities, parenting, jealousy, bad habits and more [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Unresolved conflicts and the stress associated with conflict put even the most satisfying relationship at risk [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Moreover, managing and resolving conflict is difficult, and can itself be a significant source of stress. Indeed, one of the most pressing problems couples identify is how to communicate while resolving their disagreements [ 1 , 2 , 8 ], and relationship therapists agree that dysfunctional communication is the most damaging and difficult to treat relationship problem [ 3 , 9 ]. Identifying what constitutes effective communication during conflict is thus critical to help couples resolve problems and sustain their relationships.

Unfortunately, despite decades of investigations, research investigating how couples communicate during conflict has failed to provide a definitive picture regarding the best way to resolve sources of conflict. In this article, we describe recent advances in research on communication during conflict that help to provide a more complete understanding. We focus on three significant developments. First, we move beyond conceptualizations of communication that focus on what appears to be destructive versus constructive in the moment to identify important dimensions of communication that are key to uncovering what types of communication enhance versus undermine problem resolution. Second, we show that understanding effective communication requires assessing the mechanisms through which different types of communication shape relationship satisfaction, such as whether problems improve or grow across time. Third, we illustrate that all types of communication can have beneficial and harmful effects on relationships, but whether they ultimately help or harm relationships depends on a range of contextual factors.

Conflict, Communication and Resolving Relationship Problems

Clinical researchers pioneered the investigation of communication during conflict with the aim of distinguishing distressed couples embroiled in intractable disagreements from more satisfied couples. Not surprisingly, hundreds of cross-sectional studies in this tradition revealed that dissatisfied couples exhibit greater disagreement, hostility, and criticism compared to satisfied couples who express greater agreement, affection and humor [ 10 – 14 ]. Some longitudinal studies have also provided evidence that the presence of hostile disagreement predicts declines in satisfaction, whereas expressing agreement and affection sustains relationship satisfaction [ 5 ]. These patterns suggest that communication intuitively understood as ‘negative’ is harmful for relationships, whereas more pleasant and assumed ‘positive’ communication is beneficial.

Yet, amongst this mass of studies, notable exceptions have provided contrary evidence by showing that disagreement, criticism and anger during couples’ conflict discussions predicts relative improvements in satisfaction across time [ 15 – 18 ], whereas expressing agreement and humor undermines satisfaction and stability [ 15 , 16 ]. The common thread in the explanations offered for this reverse pattern is that directly confronting problems by engaging in conflict motivates partners to produce desired changes and, thus, leads to more successful problem resolution [ 11 , 16 – 20 ]. In contrast, high levels of affection, validation and humor may soften the immediate unpleasantness of conflict but in doing so fail to motivate partners to change [ 15 , 16 , 20 ]. However, testing this explanation requires two important additions to the way researchers have typically assessed communication and its effects. Research needs to (1) more clearly identify the ingredients of communication that motivate partner change and promote problem resolution, and then (2) test whether these types of communication actually do facilitate problem resolution across time [ 5 , 21 ].

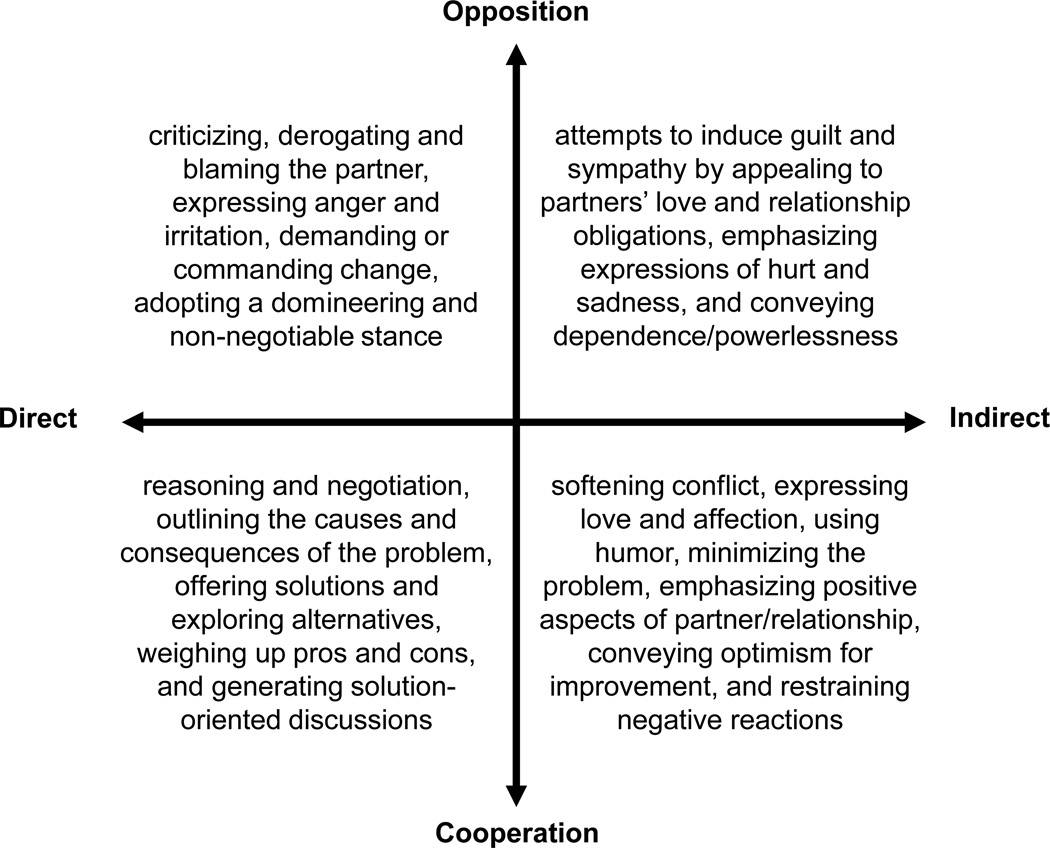

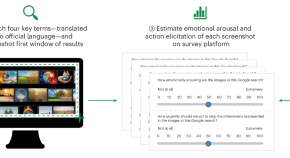

We have incorporated these two necessary components into our research programs. First, we have measured different types of communication that vary according to the two dimensions depicted in Figure 1 . The vertical dimension captures what has been traditionally understood as ‘negative’ versus ‘positive’ communication and specifies whether communication expresses opposing or contrasting goals and motivations (opposition) versus cooperative or aligned goals and motivations (cooperation). The horizontal dimension captures the directness of communication and specifies whether communication is explicit and overt (direct) versus passive and covert (indirect) with regard to the problem and how that problem can be improved. The two dimensions produce four types of communication: direct opposition (e.g., derogating/blaming the partner), indirect opposition (e.g., inducing guilt/sympathy), direct cooperation (e.g., reasoning) and indirect cooperation (e.g., softening conflict via affection).

Figure 1. Examples of communication classified according to whether the communication expresses opposition versus cooperation and is direct versus indirect.

Note. This figure provides examples of types of communication that have been commonly assessed within the conflict and influence literatures that can be classified according to two dimensions. The vertical dimension specifies the degree to which communication expresses opposing/contrasting goals and motivations (opposition) versus expresses cooperative/similar goals and motivations (cooperation). The horizontal dimension specifies whether communication is explicit and overt (direct) versus passive and covert (indirect) in regard to the problem, the change desired, and how that change can be achieved. See [ 20 , 22 ] for more detail regarding these types of communication and [ 23 – 28 ] for similar distinctions.

Second, we have assessed the degree to which these four types of communication motivate change in problems across time, which has revealed not only that opposition can sometimes have benefits but that directness is pivotal in determining problem resolution. Overall et al. [ 22 ] assessed which of the four types of communication shown in Figure 1 predicted the degree to which partners changed targeted problems across the following year. In contrast to the assumption that greater levels of opposition (top half of Figure 1 ) are inherently detrimental, greater levels of direct opposition were associated with greater change in targeted problems across time, and perceived improvements predicted increased relationship satisfaction. In independent research, McNulty and Russell [ 6 ] also found that greater levels of direct opposition when discussing relatively serious relationship problems increased problem resolution and, in turn, sustained relationship satisfaction. Moreover, both Overall and colleagues [ 22 ] and McNulty and Russell [ 6 ] found that indirect opposition was ineffective in motivating change and resolving problems.

Directness also determines whether cooperative communication is beneficial. Overall and colleagues [ 22 ] found that direct cooperation predicted greater improvement in problems across time, whereas indirect cooperation did not. Other research also supports that the types of communication classified as indirect cooperation in Figure 1 (sometimes referred to as loyalty) has limited impact on problem resolution because partners do not recognize the severity of the issue and the subsequent lack of change can leave loyal intimates feeling undervalued and disconnected [ 29 , 30 ]. In sum, an indirect, tactful approach may convey that changes are unnecessary and therefore fail to improve relationship problems. In contrast, direct communication that explicitly conveys problems need to be addressed may be more successful at improving sources of conflict.

Conflict and Communication in Context

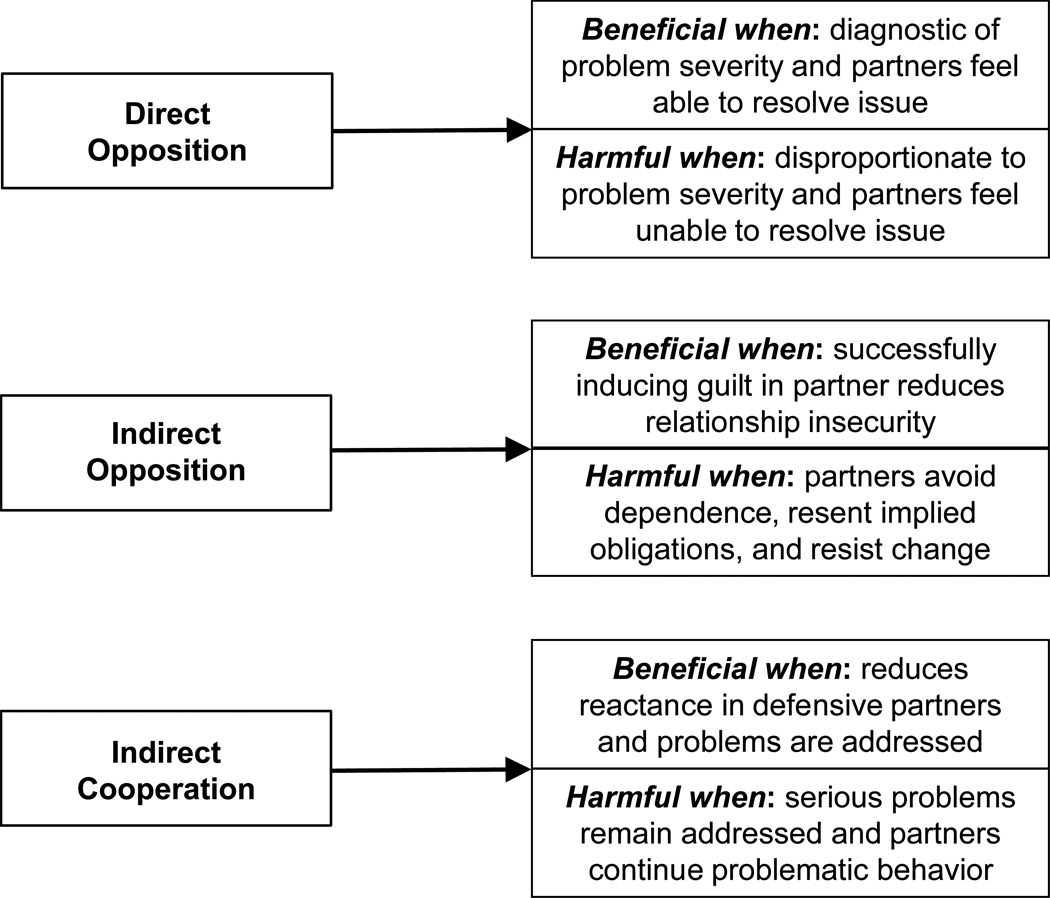

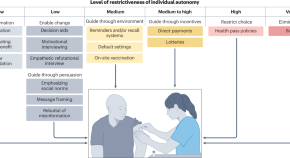

Of course, direct opposition will not always be beneficial and indirect cooperation will not always be harmful. Instead, all four types of communication have a mix of benefits and costs, and whether the benefits or costs win out depend on a range of contextual factors [ 20 , 31 – 34 ]. Examples of these contextual effects are shown in Figure 2 and discussed below.

Figure 2. Examples of contextual effects of different types of communication.

Note. This figure summarizes some examples of recent research showing that different types of communication during conflict can have beneficial effects on relationship in some contexts and harmful effects on relationships in other contexts. See [ 32 ] for a more detailed consideration of different types of contextual factors that determine the impact of communication.

With regard to direct opposition, our research has shown that whether the potential benefits (e.g., motivating partners to change) outweigh the costs (e.g., producing distress and defensiveness in partners) is determined by the degree to which (a) motivating a partner to change is necessary and (b) resolving the problem is possible [ 32 ]. Demonstrating the role of necessity, McNulty and Russell [ 6 ] found that direct opposition led to improved relationship quality when couples were facing relatively serious problems but decreased relationship quality when problems were relatively minor. When problems are serious, direct opposition matches the need for improvement and the benefits of motivating change may outweigh any costs. When problems are minor, however, direct opposition is likely to be perceived as unnecessarily harsh and leave partners feeling derogated and less motivated to be responsive. The perceived necessity of direct opposition is also likely to be why Jayamaha and Overall [ 35 ] found that direct opposition enacted by people low in self-esteem was less successful in motivating change and, in turn, reduced relationship satisfaction. Low self-esteem people chronically express negativity in their relationships [ 36 ], which may render direct opposition less diagnostic of problem severity and instead appear exaggerated or unjustified.

Whether the problem can be resolved also determines the impact of direct opposition. Direct opposition may benefit relationships if partners are or feel capable of solving the issue, but may overwhelm partners and forestall improvement attempts when they lack such efficacy. For example, people high in depression tend to make self-blaming, stable attributions [ 37 ] that lead to low efficacy and the belief that dissatisfying situations cannot be changed [ 38 ]. Accordingly, Baker and McNulty [ 39 ] illustrated that, although direct opposition tended to motivate change by partners who were low in depression, direct opposition undermined resolution efforts when partners were high in depression because those partners felt less able to address the problem. Partners’ actual ability to resolve a problem should have similar effects as perceived efficacy: direct opposition can only lead to improvements if targeted partners can actually change, but will likely only cause distress and acrimony when targeted partners are unable to change [ 32 , 40 ].

Our research has also identified other contextual factors that determine the relative benefits and costs of indirect opposition: (a) agents’ motivations for enacting indirect opposition and (b) partners’ relative vulnerability to the costs of opposition. With regard to agents’ motivations, inducing guilt does not focus directly on changing the specific problem but instead focuses on pulling reassurance of the partner’s commitment [ 20 , 22 ]. Accordingly, people high in attachment anxiety who are chronically insecure in their relationships use greater guilt induction during conflict, and successfully inducing guilt has the benefit of assuaging their insecurities [ 41 , 42 ]. However, these security-enhancing benefits are accompanied by important costs, including problems remaining unaddressed and partners becoming increasingly dissatisfied [ 22 , 41 , 42 ]. Moreover, these costs are particularly apparent when partners are high in attachment avoidance and driven to avoid the dependence and obligations to which guilt induction appeals. In particular, highly avoidant partners react with greater resistance to guilt induction, which results in lower problem resolution [ 42 ].

These same factors that determine the costs and benefits of opposition also determine the benefits and costs of cooperation: necessity of change, possibility of change, agents’ motivations, and partners’ vulnerabilities. Sustaining optimistic views of relationships can undermine satisfaction when couples face serious problems that need to be changed, but may maintain satisfaction when problems are less severe or cannot be changed ( 7 , 33 , 43 ). Other types of indirect cooperation, such as high levels of forgiveness, undermine satisfaction when partners are not responsive and problems grow, but help to sustain satisfaction when partners do alter problematic behavior [ 44 , 45 ). Indirect cooperation may also be detrimental when used to avoid guilt, tension or rejection, but be more favorable when agents are motivated to enhance and grow relationships [ 46 ]. Finally, indirect cooperation is more beneficial when vulnerable partners would otherwise be resistant to change [ 20 , 32 , 39 , 47 , 48 ]. For example, indirect cooperation reduces avoidant partners’ anger and withdrawal during conflict and, in turn, enhances problem resolution [ 48 ]. In such contexts, the need to soften defensive reactions may balance or overshadow the costs that can occur when indirect cooperation fails to generate change [ 20 , 47 , 48 ].

Conclusions

Understanding what constitutes effective communication during conflict requires (a) clarifying whether communication expresses opposition versus cooperation and represents direct versus indirect attempts to resolve problems ( Figure 1 ), (b) assessing the mechanisms through which communication affects relationships, such as motivating partners to improve problems, and (c) identifying the contextual factors that determine the relative benefits versus costs of different types of communication ( Figure 2 ). Our brief review did not cover all of the important dimensions (e.g., disengagement [ 17 , 49 ]), mechanisms (e.g., perceived investment [ 17 , 20 ]), and contextual factors (e.g., extra-dyadic stress [ 15 , 31 , 50 ]) that will determine the ultimate impact of communication. However, the research we examined demonstrated that incorporating these three components into future investigations is crucial to truly grasp the best way for couples to manage conflict. Indeed, by incorporating these three elements, recent research has challenged assumptions that disagreement and opposition is bad for relationships, and softening conflict with affection, forgiveness and validation is good. Instead, this research reveals that direct opposition can be necessary when serious problems need to be addressed and partners are able to change, but can inflict harm when partners are not confident or secure enough to be responsive. In contrast, a softer more cooperative approach involving affection and validation can be harmful when serious problems need to changed, but may be sustaining in the face of problems that are minor, cannot be changed, or involve partners whose defensiveness curtails problem solving. In short, couples need to adjust their communication to the contextual demands they are facing in order to turn conflict into a catalyst for building healthier and happier relationships.

Highlights.

How couples communicate determines conflict resolution and relationship quality

Communication can involve opposition versus cooperation and be direct or indirect

Whether communication is beneficial or harmful depends on contextual factors

Direct opposition has benefits when serious problems can and need to be changed

Indirect cooperation has benefits when problems are minor and partners are insecure

Acknowledgments

Some of the research cited in this article was supported by Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund grant UOA0811 to Nickola C. Overall, and National Institute of Health grant HD058314 and National Science Foundation grant BCS-1251520 to James K. McNulty.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Nickola C. Overall, University of Auckland

James K. McNulty, Florida State University

- 1. Papp LM, Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC. For richer, for poorer: Money as a topic of marital conflict in the home. Family Relations. 2009;58:91–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00537.x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Storaasli RD, Markman HJ. Relationship problems in the early stages of marriage. A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Family Psychology. 1990;4:80–98. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Whisman MA, Dixon AE, Johnson B. Therapists’ perspectives of couple problems and treatment issues in couple therapy. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:361–366. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Le B, Dove NL, Agnew CR, Korn MS, Mutso AA. Predicting nonmarital romantic relationship dissolution: A meat-analytic synthesis. Personal Relationships. 2010;17:377–390. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McNulty JK, Russell VM. When “negative” behaviors are positive: A contextual analysis of the long-term effects of interpersonal communication. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98:587–604. doi: 10.1037/a0017479. Two longitudinal studies demonstrate that greater direct opposition during couples’ conflict discussions predict improved relationship problems and satisfaction when problems are relatively serious, but reduced relationship satisfaction when problems are relatively minor.

- 7. McNulty JK, O’Mara EM, Karney BR. Benevolent cognitions as a strategy of relationship maintenance: “Don’t sweat the small stuff”. . . . But it is not all small stuff. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:631–646. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.4.631. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Broderick JE. A method for derivation of areas of assessment in marital relationships. The American Journal of Family Therapy. 1981;9:25–34. [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Geiss SK, O’Leary KD. Therapist ratings of frequency and severity of marital problems: Implications for research. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1981;7:515–520. [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Fincham FD. Marital conflict: Correlates, structure, and context. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:23–27. [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Gottman JM. Psychology and the study of marital processes. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:169–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.169. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Gottman JM, Notarius CI. Decade review: Observing marital interaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:927–947. [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Heyman RE. Observation of couple conflicts: Clinical assessment applications, stubborn truths, and shaky foundations. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:5–35. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.13.1.5. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Weiss RL, Heyman RE. A clinical-research overview of couple’s interactions. In: Halford WK, Markman HJ, editors. Clinical handbook of marriage and couples interventions. Chichester, England: Wiley; 1997. pp. 13–41. [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Cohan CL, Bradbury TN. Negative life events, marital interaction, and the longitudinal course of newlywed marriage. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:114–128. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.1.114. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Gottman JM, Krokoff LJ. Marital interaction and satisfaction: A longitudinal view. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:47–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.47. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Heavey CL, Layne C, Christensen A. Gender and conflict structure in marital interaction: A replication and extension. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:16–27. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.1.16. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Neuroticism, marital interaction, and the trajectory of marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:1075–1092. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.5.1075. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Holmes JG, Murray SL. Conflict in close relationships. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski A, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. New York: Guilford; 1996. pp. 622–654. [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Overall NC, Simpson JA. Regulation processes in close relationships. In: Simpson JA, Campbell L, editors. Oxford Handbook of Close Relationships. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 427–451. A general overview of the types of communication shown in Figure 1 and the benefits and costs each type of communication has for both relationship partners.

- 21. Bradbury TN, Rogge R, Lawrence E. Reconsidering the role of conflict in marriage. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, Clements M, editors. Couples in conflict. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 59–81. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Overall NC, Fletcher GJO, Simpson JA, Sibley CG. Regulating partners in intimate relationships: The costs and benefits of different communication strategies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:620–639. doi: 10.1037/a0012961. A detailed description of the foundation and development of the four types of communication shown in Figure 1 , and the first demonstration of the effects of each type of communication on change in targeted problems across time.

- 23. Canary DJ. Managing interpersonal conflict: A model of events related to strategic choices. In: Greene JO, Burleson BR, editors. Handbook of communication and social interaction skills. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 515–549. [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Falbo T, Peplau LA. Power strategies in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;38:618–628. [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Howard JA, Blumstein P, Schwartz P. Sex, power and influence tactics in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:102–109. [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Rusbult CE, Verette J, Whitney GA, Slovik LF, Lipkus I. Accommodation processes in close relationships: Theory and preliminary empirical evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60:53–78. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Sillars AL, Coletti SF, Parry D, Rogers MA. Coding verbal conflict tactics: Nonverbal and perceptual correlates of the “avoidance-distributive-integrative” distinction. Human Communication Research. 1982;9:83–95. [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Van de Vliert E, Euwema MC. Agreeableness and activeness as components of conflict behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:674–687. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.4.674. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Drigotas SM, Whitney GA, Rusbult CE. On the peculiarities of loyalty: A diary study of responses to dissatisfaction in everyday life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:596–609. [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Overall NC, Sibley CG, Travaglia LK. Loyal but ignored: The benefits and costs of constructive communication behavior. Personal Relationships. 2010;17:127–148. [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Bradbury TN, Fincham FD. A contextual model for advancing the study of marital interaction. In: Fletcher GJO, Fincham FD, editors. Cognition in Close Relationships. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1991. pp. 127–147. [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. McNulty JK. Highlighting the contextual nature of interpersonal relationships. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. (in press) A comprehensive review of the various contextual factors that influence when relationship cognitions, behaviors, and emotions have beneficial versus harmful effects on relationships.

- 33. McNulty JK. When positive processes hurt relationships. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2010;19:167–171. A concise review of four longitudinal studies that investigate the contexts that determine whether cooperation during conflict is helpful or harmful in resolving relationship problems.

- 34. McNulty JK, Fincham FD. Beyond positive psychology? Toward a contextual view of psychological processes and well-being. American Psychologist. 2012;67:101–110. doi: 10.1037/a0024572. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Jayamaha SD, Overall NC. The moderating effect of agents’ self-esteem on the success of negative-direct partner regulation strategies. Personal Relationships. 2015;22:738–761. Two longitudinal studies demonstrate that greater direct opposition enacted by people low in self-esteem is less successful in motivating problem improvement and thus undermine relationship satisfaction.

- 36. Murray SL, Rose P, Bellavia GM, Holmes JG, Kusche AG. When rejection stings: How self-esteem constrains relationship-enhancement processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:556–573. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.3.556. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Sweeney PD, Anderson K, Bailey S. Attributional style in depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:974–991. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.5.974. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Fincham FD, Bradbury TN. Cognitive processes and conflict in close relationships: An attribution-efficacy model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:1106–1118. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.6.1106. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Baker LR, McNulty JK. Adding insult to injury: Partner depression moderates the association between partner-regulation attempts and partners’ motivation to resolve interpersonal problems. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2015;41:839–852. doi: 10.1177/0146167215580777. Three studies demonstrate that greater direct opposition is associated with partners being more motivated to change undesirable behaviors when partners are low in depressive symptoms, but partners being less motivated to change when people are high in depressive symptoms because they feel less able to change.

- 40. Jacobson NS, Christensen A. Acceptance and change in couple therapy: A therapist’s guide to transforming relationships. New York: Norton; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Overall NC, Girme YU, Lemay EP, Jr, Hammond MD. Attachment anxiety and reactions to relationship threat: The benefits and costs of inducing guilt in romantic partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2014;106:235–256. doi: 10.1037/a0034371. Two longitudinal studies illustrate the benefits and costs of guilt induction (indirect opposition) communication during conflict, including highly anxious individuals feeling more satisfied and secure, but their partners becoming more dissatisfied.

- 42. Jayamaha SD, Antonellis C, Overall NC. Attachment insecurity and inducing guilt to regulate romantic partners. Personal Relationships. (in press) Three studies show that guilt induction communication (indirect opposition) is associated with lower willingness to change and lower problem resolution when partners are high in attachment avoidance.

- 43. McNulty JK, Karney BR. Positive expectations in the early years of marriage: Should couples expect the best or brace for the worst? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:729–743. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.729. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. McNulty JK. Tendencies to forgive in marriage: Putting the benefits into context. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:171–175. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.171. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. McNulty JK, Russell VM. Forgive and forget, or forgive and regret? Whether forgiveness leads to more or less offending depends on offender agreeableness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. doi: 10.1177/0146167216637841. (in press) Four studies show that forgiveness is associated with less subsequent offending among agreeable partners but more offending among disagreeable partners.

- 46. Impett EA, Gable SL, Peplau LA. Giving up and giving in: The costs and benefits of daily sacrifice in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:327–344. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.3.327. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Simpson JA, Overall NC. Partner buffering of attachment insecurity. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014;23:54–59. doi: 10.1177/0963721413510933. A concise review of the types of cooperative communication that is beneficial in reducing defensive reactions from insecure partners during conflict.

- 48. Overall NC, Simpson JA, Struthers H. Buffering attachment-related avoidance: Softening emotional and behavioral defenses during conflict discussions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2013;104:854–871. doi: 10.1037/a0031798. A dyadic observational study shows that indirect cooperation during couples’ conflict discussions is effective at reducing anger and withdrawal in highly avoidant partners and, in turn, improving problem resolution.

- 49. Christensen A, Heavey CL. Gender and social structure in the demand/withdraw pattern of marital conflict. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59:73–81. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.1.73. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Neff LA, Karney BR. Stress and reactivity to daily relationship experiences: How stress hinders adaptive processes in marriage. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;71:1155–1188. doi: 10.1037/a0015663. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (1.1 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

You are in: North America Change location

You are here

Disable vat on taiwan.

Unfortunately, as of 1 January 2020 SAGE Ltd is no longer able to support sales of electronically supplied services to Taiwan customers that are not Taiwan VAT registered. We apologise for any inconvenience. For more information or to place a print-only order, please contact [email protected] .

Communication Research

Preview this book.

- Description

- Aims and Scope

- Editorial Board

- Abstracting / Indexing

- Submission Guidelines

For over three decades researchers and practitioners have depended on Communication Research for the most up-to-date, comprehensive and important research on communication and its related fields.

Important, In-Depth Research and Scholarship Communication processes are a fundamental part of virtually every aspect of human social life. Communication Research publishes articles that explore the processes, antecedents, and consequences of communication in a broad range of societal systems. Although most of the published articles are empirical, we also consider overview/review articles. These include the following:

- interpersonal

- entertainment

- advertising/persuasive communication

- new technology, online, computer-mediated and mobile communication

- organizational

- intercultural

Why you need Communication Research

- Research and theory presented in all areas of communication give you comprehensive coverage of the field

- Rigorous, empirical analysis provides you with research that’s reliable and high in quality

- The multi-disciplinary perspective contributes to a greater understanding of communication processes and outcomes

- "Themed issues" bring you in-depth examinations of a specific area of importance, as thematically connected articles selected in the standard peer-review process are conveniently presented in a single issue

- Expert editorial guidance represents a wide range of interests from inside and outside the traditional boundaries of the communication discipline

Submit your manuscript today at https://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/commresearch .

Empirical research in communication began in the 20th century, and there are more researchers pursuing answers to communication questions today than at any other time. The editorial goal of Communication Research is to offer a special opportunity for reflection and change in the new millennium. To qualify for publication, research should, first, be explicitly tied to some form of communication; second, be theoretically driven with conclusions that inform theory; third, use the most rigorous empirical methods OR provide a review of a research area; and fourth, be directly linked to the most important problems and issues facing humankind. Criteria do not privilege any particular context; indeed, we believe that the key problems facing humankind occur in close relationships, groups, organizations, and cultures. Hence, we hope to publish research conducted across a wide variety of levels and units of analysis.

- Academic Search - Premier

- Academic Search Elite

- Business Source Premier

- CRN: Business & Industry

- Clarivate Analytics: Current Contents - Physical, Chemical & Earth Sciences

- Clarivate Analytics: Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI)

- ComAbstracts

- CommSearch - Ebsco

- CommSearch Full Text - Ebsco

- Corporate ResourceNET - Ebsco

- Current Citations Express

- EBSCO: Business Source - Main Edition

- EBSCO: Business Source Elite

- EBSCO: Communication Abstracts

- EBSCO: Human Resources Abstracts

- EBSCO: Humanities International Complete

- EBSCO: Political Science Complete

- EBSCO: Violence & Abuse Abstracts

- ERIC (Education Resources Information Center)

- ERIC Current Index to Journals in Education (CIJE)

- EServer.org

- Family & Society Studies Worldwide (NISC)

- Family Index Database

- Film Literature Index

- Gale: Diversity Studies Collection

- Humanities Source

- ISI Basic Social Sciences Index

- MLA International Bibliography

- MasterFILE - Ebsco

- OmniFile: Full Text Mega Edition (H.W. Wilson)

- Political Science Abstracts

- ProQuest: Applied Social Science Index & Abstracts (ASSIA)

- ProQuest: CSA Sociological Abstracts

- ProQuest: International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS)

- ProQuest: Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts (LLBA)

- Psychological Abstracts

- Social SciSearch

- Social Science Source

- Social Sciences Index Full Text

- Social Services Abstracts

- Standard Periodical Directory (SPD)

- TOPICsearch - Ebsco

- Translation Studies Abstracts/Bibliography of Translation Studies

- Wilson Social Sciences Index Retrospective

Manuscript submission guidelines can be accessed on Sage Journals .

- Read Online

- Sample Issues

- Current Issue

- Email Alert

- Permissions

- Foreign rights

- Reprints and sponsorship

- Advertising

Individual Subscription, Print Only

Institutional Subscription, E-access

Institutional Subscription & Backfile Lease, E-access Plus Backfile (All Online Content)

Institutional Subscription, Print Only

Institutional Subscription, Combined (Print & E-access)

Institutional Subscription & Backfile Lease, Combined Plus Backfile (Current Volume Print & All Online Content)

Institutional Backfile Purchase, E-access (Content through 1998)

Individual, Single Print Issue

Institutional, Single Print Issue

To order single issues of this journal, please contact SAGE Customer Services at 1-800-818-7243 / 1-805-583-9774 with details of the volume and issue you would like to purchase.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Submit?

- About Human Communication Research

- About International Communication Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

“what theory are you using”, theory is ubiquitous in published communication scholarship, what is theory anyway, is theory really necessary, the chicken or the egg: theory or data first, will any theory do, what is a theoretical contribution, theoretical bandwidth, what are the benefits of theory, the current state of communication theory, looking forward, data availability, conflicts of interest.

- < Previous

The role of theory in researching and understanding human communication

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Timothy R Levine, David M Markowitz, The role of theory in researching and understanding human communication, Human Communication Research , Volume 50, Issue 2, April 2024, Pages 154–161, https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqad037

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Communication is a theory-driven discipline, but does it always need to be? This article raises questions related to the role of theory in communication science, with the goal of providing a thoughtful discussion about what theory is, why theory is (or is not) important, the role of exploration in theory development, what constitutes a theoretical contribution, and the current state of theory in the field. We describe communication researchers’ interest with theory by assessing the number of articles in the past decade of research that mention theory (nearly 80% of papers have attended to theory in some way). This article concludes with a forward-looking view of how scholars might think about theory in their work, why exploratory research should be valued more and not considered as conflicting with theory, and how conceptual clarity related to theoretical interests and contributions are imperative for human communication research.

Theory looms large in the practice of human communication scholarship. College-level textbooks on various communication topics describe relevant theories to students enrolled in communication classes. In thesis and dissertation defenses, students are often asked, “What theory are you using?,” implying that they must apply at least one theory to ground their research and contribute to the field. In the peer-review process of academic journals, a perceived failure to be sufficiently theoretical can be grounds for rejection. Few, if any, modern communication scholars would embrace the labels of being “dust-bowl” or atheoretical. Surely, no serious communication scholar is genuinely and categorically against theory. Theory is undeniably a desirable “warm-fuzzy good thing” in modern academic culture ( Mook, 1983 ). Without it, the bedrock of communication and other social sciences is shaky and uncertain. No academic discipline could be built from a purely empirical foundation. Having theory—understanding the value it provides, what we gain by building and extending theory, and the contributions that a scholar can make to theory—is more complicated and nuanced, however. We interrogate these complications in this article.

This article addresses a broad set of questions about the past, present, and future role of theory in communication scholarship: What is theory? Do all scholarly contributions require theory? What does it mean to make a theoretical contribution? What does theory do for us? And, if we continue to accept theory as a scholarly imperative, what is the current state of theory in the field and where might communication theory go in the future? To address these questions, we follow and draw on important commentaries such as those of Chaffee and Berger (1987) , Slater and Gleason (2012) , and DeAndrea and Holbert (2017) , but we provide our own perspective. Unlike similar essays on communication theory, our goal is not to be prescriptive about how to do theory (e.g., how to create or even define theory), nor are we attempting to be pollyannish about the many accepted virtues of theory. Instead, a conversation about communication theory is advanced by asking questions that are hard to answer, interrogating some often-implicit presumptions about the role of theory in communication science, and raising some less obvious implications of theory. This article will succeed if it prompts deeper thought and discussion on the topic of communication theory across many areas of the field. We envision this being useful for early career communication scholars who are uncertain about what theory really is and why it matters, and a thoughtful commentary for seasoned communication researchers who may wrestle with theory development as they move forward in their established research programs.

In our experience, graduate students (and undergrads, junior faculty, visiting scholars, etc.) are frequently asked “what theory are you using?” when trying to position one’s work within communication science at large. This question raises many meta-theoretical issues relevant to this article. First, the question implies that theory is a prerequisite for scholarship. Later in this article, we will argue that this perspective is unfortunately limiting, and that there is a need for exploratory and pre-theoretical inquiry and data. Further, a relevant theory is not always available for each research interest. A better initial question, in our opinion, asks if there is a relevant theory to be tested, extended, or used. When no relevant theory exists, the lack of a theory should not preclude research nor publication. Advancing theory is undeniably valuable. Not all scholarly contributions, however, explicitly advance theory in ways that are recognized at the time they are written.

When a relevant theory or theories are available, follow-up questions might address how the theory is being engaged (cf. Slater & Gleason, 2012 ). Is the theory being directly tested in a way that is informative about the merits of the theory? How is the theory being advanced? Is a boundary condition being explored or the scope being extended? Merely using a theory to inform a topic can provide valuable direction and insights, but using theory is less likely to push the theory and its related propositions forward. Making a theoretical contribution involves actually advancing the theory itself ( Slater & Gleason, 2012 ).

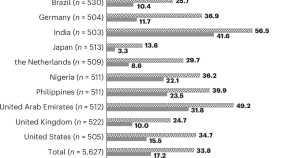

We opened by opining that communication scholarship is consumed with theory and that contributing to theory is a priority of the discipline. To descriptively demonstrate this extent of this interest, we evaluated over 10,000 full text communication articles across 26 journals that were published in the last decade (see Markowitz et al., 2021 ), in search of how often they focus on five key theory-related terms ( theory , theories , theoretical , theoretical contribution , theoretical contributions ). The top panel of Figure 1 represents the percentage of papers within each year that mentioned at least one of the five terms related to theory. On average, 79.1% (8,320 of 10,517) of articles mentioned one theory-related term, with a relatively stable distribution over time (see the bottom panel of Figure 1 for a breakdown by journal). Of the 60,727 times that one of the five theory-related terms appeared in the sample, over half were related to the word theory alone (55.1%; 33,462/60,727). A thematic review of these cases revealed that theory is used in a variety of ways by communication researchers. The word is attached to specific social scientific theories (e.g., Construal Level Theory, Social Identity Theory), the term is used abstractly to feign the appearance of theory (e.g., “message processing theory,” “organizational communication theory”), the word theory serves as sign-posts in academic papers (e.g., “in the theory section above”), and finally, the term attempts to mark one’s contributions (e.g., “has several implications for theory and research on selective exposure”). 1 Together, the ubiquity of theory and theory-related terms, we believe, stems from and reflects expectations for publishing norms that value theory in the field of communication.

The rate of mentioning theory in communication science articles.

Our findings align with those of Slater and Gleason (2012) who examined articles in three elite communication journals in 2008–2009. They report that a sizable number of articles advanced theories in at least one of several ways. They reported, for example, that 54% of the articles they examined in Journal of Communication , Human Communication Research , and Communication Research addressed boundary conditions, 40% expanded a theories range of application, 22% advanced a mechanism, and 12% revised a theory. Alternatively, theoretical contributions, such as creating a new theory, comparing theories, and synthesizing across theories, were less common occurring in only 8% of articles combined.

We note, however, that mentioning at least one theory-related term does not mean that the work counts as contributing to theory. Of course, deeply theoretical work mentions theory, but so too do articles that engage in a practice that might be called theoretical name dropping . Our concern is that if work must invoke theory to pass the peer-review process, then exploratory and pre-theoretical work might mention a theory or otherwise invoke theory-related words to appear theoretical and thereby get published. In line with this concern, DeAndrea and Holbert (2017) found that the use of words in articles specifically related to theory evaluation were infrequent. In a sample of articles from four top journals between 2013 and 2015 ( Journal of Communication , Human Communication Research , Communication Research , Communication Monographs ), just less than one-third of them included at least one theory evaluation word, and at least half of those were evaluating method rather than theory.

Deciding what is truly theory and what is not requires defining theory. This is where our conversation becomes more complex.

Despite the ubiquity of researchers’ focus on theory in published communication scholarship ( Figure 1 ), any thoughtful discussion of theory is fraught from the start due to unavoidable definitional ambiguity. There is no one definition of communication theory, nor can there be, nor should there be. As Miller and Nicholson (1976) rightfully suggested, definitions are not by their nature things that are correct or incorrect. Although undeniably circular, words mean what people mean by them, and people use words differently. This is especially true of theory. No one scholar, nor do a collection of scholars, become the definitive authority or arbitrator on what theory is and what it is not.

Definitional diversity in conceptually constituting theory is intellectually rich. In modern intellectual thought, different specialties and perspectives are welcomed and valued. The alternatives to diversity in theory definitions are hegemony and the demise of academic freedom. Treasured intellectual diversity, however, comes at the cost of potential misunderstanding stemming from people using the same word to mean so many different things (e.g., see Bem, 2003 ). Valuing intellectual diversity also requires us to abandon rigidity in prescribing fixed rules of doing communication theory and research.

Although there can be no one universal definition of theory, we agree with DeAndrea and Holbert (2017) that regardless of approaches, scholars should strive for greater clarity in what they mean by theory and their theoretical contribution. Diversity in definitions should be expected, but clarity and the thoughtful explication of one’s approach to theory should also be expected in any social science.

The lack of a shared definition for theory puts communication scholars in a Catch-22. Communication scholars value theory and appreciate approaching theory with rigor and clarity. Communication scholars also value intellectual diversity, and valuing diverse perspectives and approaches prevents scholars from imposing their own views of theory on other scholars. We find that an “anything goes” approach to theory intellectually troubling, but we are equally disturbed by imposing views and perspectives on other scholars. While we do not see an easy way out of this conundrum, we see much value in acknowledging that it exists and being thoughtful about how we balance conflicting values.

When scholars define theory, perhaps the most notable dimension of variability for the word theory is narrowness-breadth. At the wide end of this continuum, theory is synonymous with being minimally conceptional. Explicating a construct with a conceptual definition could constitute theory under some of the more expansive uses of the term (cf. Slater & Gleason, 2012 ). Similarly, at the broad end of the continuum, theory can be synonymous with explanation. Efforts to answer “why” can count as theory. Sometimes, although we personally think this goes too far, simply adding the word theory to a topic or phenomenon (e.g., media theory, aggression theory, language theory) can pass as theory or at least provide the appearance of theory.

We prefer a much narrower use of the term, where theory can be considered a set of logically coherent and inter-related propositions or conjectures that (a) provide a unifying explanatory mechanism and (b) can be used to derive testable and falsifiable predictions . In this relatively narrow view, thinking conceptually or just explaining is not enough. Specifying a path model or set of mediated links might or might not count as theory. We note that some scholars may use the word theory even more restrictively, desiring to limit the term to formal axiomatic theories, and considering work to count as theoretical only if it conforms to a strict hypothetico-deductive depiction (or caricature) of science. Slater and Gleason (2012) provide a definition similar to ours. They see “the primary role of theory in communication science as the provision of explanation, of proposing causal processes, the explanation of ‘how’ and ‘under what circumstances’ in ways that result in empirically testable and falsifiable predictions” (p. 216).

The point here, however, is not to advocate for particular definition of theory but instead to argue that the efforts to impose a universal definition of theory is fundamentally misguided. Appreciation of theory requires recognition of the diversity of approaches to theory and a willingness to be respectful of approaches other than one’s own. The topic of theory needs to be approached with a cognizance of its diversity. Arguments about whose definition of theory is best will often be counterproductive. More constructive arguments will provide cogent reasons why an approach to defining theory is best for the intellectual endeavor to which it is applied.

Now that we have embraced the ambiguity inherent in defining theory, we next contemplate the necessity of theory. If we cannot provide a consensus definition of theory, then how can we demand or test it? Do (or would) we even know theory when we see it?

In our view, the necessity of theory varies according to the breadth of the term’s use. Being minimally conceptual is probably a prerequisite for making a scholarly contribution. After all, understanding what one is studying is typically either a prerequisite for, or a desired outcome of, advancing knowledge. If scholarly activities — such as concept explication, creating a new measure, description, observation, and hypothesis generation — indeed count (see Slater & Gleason, 2012 ), then requiring theory seems constructive.

One can imagine empirically documenting an effect or phenomenon whose explanation is not yet understood. While this might not count as a theoretical advancement under most uses of the term, it might nevertheless make a valuable contribution to knowledge. If nothing else, we typically need to know what needs explaining before we go about explaining it ( Rozin, 2001 ). Thus, disregarding the contribution of scholarship that is not “full-on” theory in some narrow sense is counterproductive to the advancement of knowledge.

Park et al. (2005) provide an instructive example. Their first study simply documents the existence of a strong finding. Unlike in the United States, Korean spam emails often contain an apology. What follows are five experiments testing various explanations before settling on a normative account. The work is not grounded in a specific theory, but it is clearly a systematic effort to document and explain a communication phenomenon. What if, however, they had packaged their studies as a series of articles rather than in one. Would this make the work any more or less theoretical?

One of the more controversial, meta-scientific questions in communication science is: Must we have theory? We answer “yes” in the broadest sense, as it helps to clarify our thinking about a topic. We also answer “no” in a narrower sense of theory. In explaining why not, we acknowledge that it would also always be better if we had at least one good theory than if we did not. Nevertheless, a well-articulated and relevant theory is not currently available for every conceivable topic or hypothesis worthy of investigation. It is not hard to imagine useful and enlightening scholarship that is neither formally engaged in theory building nor explicitly testing an existing theory. Simply put, if one is interested in a question or phenomenon where suitable theory is currently lacking, this ought not preclude research. Consequently, it follows that not all valuable scholarship requires theory in the narrow sense.

Which comes first, theory or data? The answer is it can be either, or the two can work together in an iterative, interactive, and abductive process ( Rozeboom, 2016 ). Different disciplines and specialties put a different emphasis on the primacy of theory in empirical research. Communication, on the one hand, sometimes views a strict hypothetico-deductive dogma as the ideal for formal theory testing, presupposing an existing formal theory from which to derive hypotheses. Computer science, on the other hand, is typically less strict in its placement or appreciation of theory in the research process. Quite often, computer scientists will obtain data, analyze them, and then identify the theory or theories that fit the findings as a final step. A communication scholar may scoff at this research process, though norms are powerful drivers of behavior ( Cialdini, 2006 ), and conventions related to theory are to be appreciated and scrutinized within the context of a discipline, specialty and even sub-specialty.

Building theory can be a purely logical process, but we are likely to develop more and better communication research if relevant data from exploratory research is available. Exploratory research, we contend, is not synonymous with being atheoretical. We tentatively define exploratory research as research guided by curiosity and seeking to document a finding or set of findings rather engaging in hypothetico-deductive hypothesis testing or focusing on explanation . We further note that not all hypothesis tests are theoretical. The logic behind hypotheses often takes the form of “others have found this, therefore we will too.” Such research falls in between more purely exploratory work and explicit theory testing where hypotheses follow from theory.

We contend that exploration is symbiotic with and often contributes to theory because it can highlight relationships that were unanticipated by theory, offering new hypotheses for future research. Even purely descriptive research can provide an understanding of the phenomena of interest, thereby providing a solid empirical foundation for conceptual construction. The placement of theory in the research process is not specifically a statement about the work’s value or rigor; it likely emphasizes the goals and norms of a particular research community. Consistent with our views on defining theory, we encourage our colleagues to be ecumenical in approaching theory-data time ordering.

An even more difficult question asks if all theories are equal. If some theories are indeed better than others, then what makes them so? Are there instances when no applicable theory is preferred to a misapplied or unreliable theory?

At the risk of diverting from our previous, more ecumenical perspective, we will tentatively take the position that some theories are indeed preferable to other theories—at least for certain applications—and along certain criteria of evaluation. For example, DeAndrea and Holbert (2017) expanded on Chaffee and Berger’s (1987) list of criteria for evaluating theory. Their refined list includes explanatory power, predictive power, parsimony, falsifiability, logical consistency, heuristic value, and organizing power. Building on this work, we further cautiously propose that theory can do more harm than good when it is misapplied, used haphazardly, or thrown at data to see if it sticks. If the goal of scholarship is the pursuit of knowledge and understanding, it seems possible that certain frames, stances, models, and understandings might be counterproductive or misguided.

From our perspective, a first consideration regarding the utility of theory is one of relevance. Does the sphere of application fall within the boundary conditions of the theory, or does the application involve interrogating the boundary conditions of the theory? If the answer to both questions is no, then the application is probably ill-advised on the grounds of relevance. Irrelevant theory distracts from empirical contributions. This is the theoretical equivalent of a red herring argument.

The second test is more difficult and involves a cost–benefit analysis of gains and losses in knowledge, insight, and understanding. Consistent with commentators such as Levine and McCornack (2014) , we envision evaluative dimensions, such as clarity, coherence, and verisimilitude, in assessing the scholarly value added by a theory. The more that a theory clarifies rather than clouds our understanding, the more valuable it is. Theory can bring order to otherwise unruly facts, findings, and ideas, or it can lead to logical inconsistencies, the latter obviously being less desirable. The insights offered by theories can align with known facts and findings or it can be contradicted by data and evidence ( Levine & McCornack, 2014 ).

In practice, assessing the alignment of theory with data is an especially thorny issue in quantitative, social scientific communication research. Not all scholarship strives to be empirical nor scientific, and theory-data alignment might not be the point in many scholarly endeavors. But when it is, theory-data alignment quickly becomes deeply problematic in the actual practice of communication scholarship, particularly when inferential statistics, and especially p -values, are involved ( Denworth, 2019 ).

One issue concerns “undead theories” ( Ferguson & Heene, 2012 ). It is not unusual in the social sciences for theoretical predictions to be soundly falsified, yet, nevertheless, applied despite their documented empirical deficiencies. Such theories are functionally sets of counterfactual conjectures that are passed off as good science. We anticipate that the reader will have their favorite undead theory, but we also anticipate that one scholar’s undead theory is another’s source of wisdom. Both can be true, which we appreciate, and will explain.

While the replication crisis in the social sciences has become an increasingly recognized issue ( Open Science Collaboration, 2015 ), it has also long been recognized that modern social science practices ensure that almost any hypothesis will receive mixed support regardless of its validity or verisimilitude ( Meehl, 1978 ). Essentially, the fact that the nil-null hypothesis is never literally true regardless of the soundness of the theory (Meehl’s crud factor), sub-optimal statistical power, questionable research practices such as p -hacking, and publication bias all combine to make the empirical merit of any claim murky at best ( Dienlin et al., 2021 ; Lewis, 2020 ; Markowitz et al., 2021 ). Accumulating more data over time often further muddies the water as mixed findings pile up and multiple citations can legitimately be provided in support of incompatible empirical claims. Not even meta-analysis is immune. As prior work shows ( Levine & Weber, 2020 ), regardless of the topic, findings in communication are heterogeneous, and the heterogeneity is seldom resolved by moderator analysis. In this way, meta-analytic results often document rather than resolve conclusions of mixed support for theoretical predictions. The net result is that a theory’s supporters and critics can both provide plenty of citations for why the theory is well supported and clearly falsified.

A common concern in academic research publishing is to articulate how one’s work makes a substantial theorical contribution ( DeAndrea & Holbert, 2017 ; Slater & Gleason, 2012 ). Articles in flagship, high-impact communication journals are often rejected if theoretical contributions are not substantial and clearly expressed. For example, the Journal of Communication suggests “Submissions are expected to present arguments that are theoretically sophisticated, conceptually meaningful, and methodologically sound” ( Journal of Communication, 2022 ). The words sophisticated and meaningful in their instructions for authors are subjective and elusive. Considering the subjective aspect of such appraisal, what does it mean to make a theoretical contribution?

Given that we have argued so far that defining theory is misguided, that formal theory is not necessary for all research endeavors, and that unequivocally establishing the empirical merit of theory is nearly impossible, one might expect an argument dismissing the very idea of theoretical contribution. A close read of what preceded, however, conveys several ways to make a theoretical contribution (cf. Slater & Gleason, 2012 ). Clarifying a conceptualization, providing an explanation, making or testing a prediction, testing theoretical boundary conditions, articulating a unifying framework integrating two or more seemly unrelated facts, and identifying a moderator that resolves previously unexplained heterogeneity can all count as theoretical contributions if done in a way to be conceptually coherent. One can seek to create new theory, pit existing theories against each other, or reconcile apparently conflicting theories. In our view, all such outcomes can offer new knowledge that conceptually builds on an existing foundation of empirical findings.

Critically, a theoretical contribution is different from discovering a new, statistically significant finding. Moving from empirical findings to theoretical contribution involves answering questions related to the mechanism underlying the finding. How does the finding fit within the larger nomological network of findings in the domain ( Cronbach & Meehl, 1955 )? What are the limits of the finding? How robust is it? How far can it be generalized? What are its moderators and antecedents? These questions, among many others, may help to position a finding better as a theoretical contribution instead of an empirical one-off result.

The most basic types of theoretical contributions are conceptualizing or explicating a new construct, reconceptualizing an existing construct, or providing a new explanation for an empirically documented effect. These types of contributions might be considered theoretical building blocks for subsequent theoretical development. Although these types of contributions may also be seen as just minimally theoretical, they are nevertheless important because other types of theoretical contributions require well explicated components and explanations. Coherent conceptual structures can lead to testable and falsifiable hypotheses about human communication and logically coherent networks of hypotheses can lead to formal theory.

A second approach to theoretical contribution involves variations on theory creation. Arguments for the desirability of a new theory will often take one of three forms. The first notes the absence of a relevant theory for a given topic or purpose. If no relevant theory exists and if theory is desired, then it follows that theory creation is needed. The second type of argument rests on making the case that existing, relevant theory is deficient, and the deficiencies are both sufficiently severe and intractable to justify a new theory as a rival. Third, prior theory can be accepted, but arguments are made that the new perspective offers additional insights that would not otherwise be gained.

Once a theory exists in the literature, it is often the goal of communication research to test, extend, modify, or apply a theory to improve our understanding of human communication. Each of these (testing, extending, modifying, or applying) moves communication theory forward. We note, however, that at least for scientific research, testing should typically precede the other forms of contribution to ensure theoretical adequacy prior to extension or application.

Many discussions of theoretical contributions will involve value judgments regarding theoretical bandwidth. Discussions of theoretical bandwidth, in turn, may deal with two qualitatively different issues. The first relates to how theory is defined. One might think of explicating a construct as a narrower contribution than explaining the relationship between two explicated constructs. Explaining how a well-understood effect fits with a network of documented effects is broader still.

Second, communication theories vary widely in their topical scope and boundary conditions. Communication theories might focus on a particular topic or phenomenon, others on a broader domain or function, and others still might be general theories of communication. Further, regardless of topical breadth, boundary conditions can vary. Communication theories, for example, might be limited to a particular age group, point in time, media, or culture.

It is likely tempting to equate theoretical bandwidth and theoretical contribution under the likely tacit presumption that more is better. While surely there are knowledge-gain advantages to breadth, any firm link between breadth and contribution is qualified by all other things being equal. Surely contribution is more closely tied to how well a theoretical goal is accomplished than to how ambitious the goal is (cf., DeAndrea & Holbert, 2017 ).

Rather than reviewing the extensive literature on the value of theory, we focus here on two benefits of theory that we believe are highlighted less frequently but are no less important.

Generality and external validity

Perhaps the most underappreciated benefit of theory is that it can provide satisfying answers to questions of generality in ways that data simply cannot. Theory is a better approach to achieving external validity than research design.

We have all seen data collected on college students and wondered if the findings might apply to working adults. We all likely agree that for most topics, a nationally representative sample is preferable to a sample of college students (though, see Coppock et al., 2018 ). Nevertheless, we might still wonder that if the data were collected at a different point in time, or if the questions were worded a bit differently, or perhaps presented in a different order, would the findings be the same? These sorts of questions cannot be answered with data because we can never sample everyone everywhere over all times in all possible ways. No matter how much data we have, data are finite, and representative sampling and inferential statistics do not change this uncomfortable truth.

Fortunately, theory provides an elegant solution. Theoretical claims specify what is expected under what conditions. Theory, and more precisely its boundary conditions, provide us with statements of the extent of generality. As described by Mook (1983) , we specify generality theoretically, then we test and validate claims of generality with data. Rather than fretting over the sampling of participants, multiple message instantiations, multiple situations, and a host of other study-specific idiosyncrasies, we use theory to make generalizations and data to test those generalizations ( Ewoldsen, 2022 ). We could ask if a theory applies to non-WEIRD cultures, and then test core claims with a non-WEIRD culture ( Henrich et al., 2010 ; Many Labs 2, 2018 ).

Theory as agenda setting

A second underappreciated function of theory is research agenda setting. Just as the media might tell us which news topics and frames are important, so too does theory tell us what we need to study, how to study it, and what to expect. It is not unusual for new researchers to struggle with topic selection. Theory provides a straight-forward way to come up with a hypothesis and an approach to testing it. This topic selection approach can also be flipped. We can ask, what if a theory was wrong? How might we show that? A research design should flow from these questions.

Theory offers an even more important agenda setting function. As Berlo (1960) famously identified when defining communication as process, a wide variety of forces can affect how communication unfolds. Regardless of the specific topic or focus, the potentially important considerations are numerous. Theory tells us what is most important and what is less important. In other words, theory tells us what to prioritize.

We are more pleased than not with the current state of communication theory as its progress is undeniable. There was a time when the lack of communication theory was bemoaned and when most theories were taken from other disciplines (see Berger, 1991 ). Our perception of the current literature, formed by our lived experience across decades of publishing and reading communication scholarship, is that the number of communication theories and theoretical ideas have grown, and the communication trade deposit with related fields has diminished. The latter point, of course, deserves a strict empirical evaluation to test how communication and other social sciences share ideas and theories.

As the reader has surely noticed, we have approached this article from a particular perspective. The present authors have a quantitative and social scientific approach to communication scholarship. A consequence of originating from this scholarly tradition is that our commentary is better targeted for research publishing in outlets such as Human Communication Research than outlets like Communication, Culture, & Critique . Both are worthy outlets, but they have different orientations and conventions.

Like most communication scholars, we are theory advocates. We use, have written our own, and made contributions to theory on a range of topics relevant to human communication. While we ascribe to the idea that “there is nothing so practical as a good theory” ( Lewin, 1951 , p. 169), blind allegiance to theory is ill-advised. Theories, we believe, must have testable and falsifiable components to them. We encourage our fellow communication scholars to “follow the data.” Moving science forward requires theoretical predictions that hold up to data over time.

Replications play an increasingly important role in theory testing, but also add a final set of complications to address. Theory and evidence can misalign for several reasons, and it is usually unclear why a test failed. Perhaps some critical aspect of the research setting was different, producing an unexpected result. A moderating variable may have impacted the results, such that the findings do not invalidate the theory, but instead provides a nuanced understanding of the conditions that led to a particular effect and those that did not (or led to the opposite effect). Theory should be a guidepost for empirical research, not gospel, upon considering the results. Of course, theory and data can also misalign because the theory is mis-specified. In practice, it can be difficult to discern valid support from false positives and mis-specified predictions from a methodological artifact or undetected moderators. Nevertheless, we envision a future where replication is both more prevalent and more valued.

Communication is an eclectic discipline, and science is not the only method for understanding communication. Further, we as a field draw on and adopt ideas from different fields, authors publish in journals outside of communication research, and there is no singular approach to the same research question. We encourage authors to continue this tolerance and flexibility with exploratory and “pre-theory” work as well. As mentioned, there are times when a good theory simply does not fit one’s phenomenon of interest. Communication scholars should not be faced with a “square peg, round hole” problem just to satisfy reviewers who demand more theory. One can try to fit a square peg into a round hole with enough force, but it will not fit well and there may be important consequences because of this exercise (e.g., theory–data misalignment). Exploratory work should be considered and applauded when we simply do not know how concepts will relate to each other. Proposing a research question instead of hypotheses derived from theory is not an admission of a research study being atheoretical, but instead, an admission of one’s curiosity and uncertainty. Thus, we envision a future where exploratory and descriptive work is more prevalent and more appreciated.

It is also important for authors to think about and explicitly communicate the role of theory in their research. This article has noted the many functions that theory can serve; yet, these functions are often assumed or implied in a manuscript when they could be made explicit. Being forthcoming about the role of theory in one’s research will lead to conceptual and contribution-related clarity. This will lead to less superficial applications of theory (e.g., theoretical name dropping ) and toward more conceptual richness. If communication research is to value theory—and we undoubtedly think it should—then theory should be used appropriately. Theories are built on a foundation of empirical evidence, collected over time allowing researchers to draw nuanced conclusions and make subsequent predictions about human communication. Using the term theory to sound more scientific, rigorous, or grounded is gratuitous and should be avoided. Consequently, we envision a future where communication theory, in form and function, is used more thoughtfully and transparently.

Finally, we are encouraged that all major communication research journals have a large focus on theory in their articles (e.g., at least 50% of articles in each journal mention theory in some manner; Figure 1 ). However, the degree to which the published communication literature is advancing theory in consequential ways or settings is unclear ( DeAndrea & Holbert, 2017 ). We encourage scholars to be flexible with their assumptions about a theory, testing it in ways that might be unconventional and creative in the pursuit of new knowledge. To this end, null effects are still informative ( Francis, 2012 ; Levine, 2013 ), especially if a study is adequately powered. For example, understanding what leads to null effects might be helpful for the development of boundary conditions of theory. Null effects are difficult to publish, but communication research can lead in their normalization in the pursuit of greater theoretical precision and explication. Thus, we envision a future where researchers are more frank about empirical support, and more precise with predictions.

Data related to Figure 1 can be retrieved from Markowitz et al. (2021) or by contacting David M. Markowitz.

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors also report no conflicts of interest with the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.