Home — Essay Samples — Government & Politics — Nationalism — The Spread of Afrikaner Nationalism in South Africa

The Spread of Afrikaner Nationalism in South Africa

- Categories: Nationalism South Africa

About this sample

Words: 2180 |

11 min read

Published: Feb 12, 2019

Words: 2180 | Pages: 5 | 11 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, the great trek: a battle for survival, the ‘poor white problem’, afrikaner nationalism essay conclusion.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Government & Politics Geography & Travel

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1380 words

3 pages / 1549 words

6 pages / 2528 words

1 pages / 606 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Nationalism

White nationalism and extremism have unfortunately become increasingly prevalent in educational institutions in recent years, sparking concerns and debates about the roots of this troubling trend and how to address it [...]

Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914, the First World War erupted and endured until 1918. This catastrophic conflict embroiled a coalition comprising the United Kingdom, France, Russia, Italy, [...]

Nationalism and sectionalism are two concepts that have played a significant role in shaping the history and politics of the United States. While both ideologies have had an impact on the development of the nation, they are [...]

Imagine a time when the world was on the brink of change, when societies were transforming, and nations were awakening to their own unique identities. This was the era of nationalism in the 1800s - a profound movement that swept [...]

June 26, 1963, post WWII, a time were the United States and the Soviet Union were the world’s superpowers. The two powers fought a war of different government and economic ideologies known as the Cold War. During the time of the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

Culture and power: the rise of Afrikaner nationalism revisited*1

2010, Nations and Nationalism

Related papers

International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2000

The study of international intellectual networks has the potential of making an important contribution to South African historiography, in particular the study of Afrikaner nationalism. Afrikaner nationalism itself is shrouded in mythology and has, rightly or wrongly, been equated with white racism and apartheid. For a large part of the twentieth century, an influential theory held that Afrikaner nationalism and racism was the result of an isolationist frontier mentality. According to this theory, Dutch frontier farmers moved deep into the South African interior where they led an isolated existence, maintaining a “primitive” 17th century Dutch Calvinism, far removed from intellectual developments in Europe. This theory was challenged by Marxist scholars in the 1970’s, but the basic isolationist myth was never addressed – and therefore never questioned. However, when the number of prominent Afrikaners, who studied in Europe, and especially in the Netherlands, is taken into account, the perception that Afrikaner nationalism was an isolated phenomenon becomes problematic. Three successive 20th century South African prime ministers studied in Europe – and two of them in the Netherlands. Of these, Dr. D.F. Malan is of particular interest. He studied theology at the Stellenbosch Seminary, which was established by Utrecht alumni, and followed the example of his professors by pursuing further studies at the University of Utrecht, where he obtained a Doctorate in Divinity in 1905. His arrival in Utrecht in October 1900 coincided with the Dutch public’s passionate displays of sympathy for their stamverwanten in South Africa who were fighting in the Anglo-Boer War. Being in the Netherlands enabled Malan to observe and grasp the realities of European power politics, which prevented the Dutch government from providing any substantial support to the Boers. He travelled the European continent at a time when nationalism was as yet untested by the horrors of the First World War and his contacts with international students at a students’ conference in Denmark confirmed his belief in the virtues of cultural diversity, much in the spirit of the German philosopher, Herder. The influence exerted by Malan’s Dutch mentor, Prof. J.J.P. Valeton Jr. was also significant: at a time when Abraham Kuyper was prime minister, Valeton taught Malan that politics and religion were irreconcilable. Malan made Valeton’s views his own, and refrained from politics for ten years after completing his studies, but after great internal struggle, his career eventually followed the same pattern as Kuyper’s. The aim of this paper is to investigate the influence of D.F. Malan’s studies at the University of Utrecht on his formulation of Afrikaner nationalism, and through this, to place Afrikaner nationalism within a broader, international context. This will challenge the myth that Afrikaner nationalism was formulated by people who were isolated from intellectual movements in Europe.

In this article I investigate the relationship between Afrikaner nationalism, apartheid and philosophy in the context of the intellectual history of the University of the Free State. I show how two philosophers that were respectively associated with the Department of Political Science and the Department of Philosophy, H J Strauss (1912-1995) and E A Venter (1914-1968), drew on the philosophy of Herman Dooyeweerd to justify separate development. I argue that their interpretation does not simply amount to a wilful misunderstanding of Dooyeweerd, but rather that the foundational moment of Dooyeweerd’s philosophy involves an interpretive violence that accommodates this intepretation.

The role of the missionaries in the conquest of Afrika has led to the emergence of "Afrikan liberalism" and its idea of Afrika. Christianity and European miseducation as instruments of epistemicide created a group of "new Afrikans" who, as the leading ideologues of the conquered Afrikans, were infected with European liberalism and humanism. The latter are the conditions necessary for the propagation of an inclusive Afrikan nationalism which seeks to integrate non-Afrikans, such as Europeans and Asians, into Afrika. Anton Lembede, who was a member of the new Afrikans, propagated the political philosophy of Afrikanism, which was premised on an exclusive idea of Afrika for the Afrikans. Robert Sobukwe and Steve Biko, through A. P. Mda's idea of "broad nationalism", pursued an inclusive idea of Afrika. This article seeks to foreground Lembede's exclusive idea of Afrika in contrast to the Azanian tradition's non-racial and inclusive idea of Afrika, as encapsulated in Sobukwe's metaphor of the Afrikan tree and Biko's metaphor of the Afrikan table. This article engages in a brief comparative analysis of two forms of Afrikan nationalism in South Africa to underscore the two ideas of Afrika.

Nations and Nationalism, 2002

In Neville Alexander and Arnulf von Scheliha (eds.). 2014. Language policy and the promotion of peace. African and European case studies. Pretoria: UNISA Press., 2014

The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 1989

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

Nations & Nationalism, 2023

De Gruyter eBooks, 2023

New Contree

Journal of Southern African Studies, 2007

Journal of Southern African Studies, 2000

The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 1999

African Studies, 1981

Leidschrift 4 (June 1988), 93-103., 1988

en.scientificcommons.org

Academia Letters, 2021

Religion and Neo-Nationalism in Europe

Apartheid still exits South Africa, 2019

South African Historical Journal, 2008

Africa Spectrum

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > The Journal of African History

- > Volume 33 Issue 2

- > Afrikaner Nationalism, Apartheid and the Conceptualization...

Article contents

Afrikaner nationalism, apartheid and the conceptualization of ‘race’.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 January 2009

This paper analyses the ideological elaboration of the concept of race in the development of Christian-nationalist thought. As such, it contributes to our understanding of the ideological and theological justifications for apartheid. The paper begins by pointing to the relatively late moment ( c. mid-1930s) at which Afrikaner nationalist ideologues began to address the systematic separation of blacks and whites. It takes its cue from a key address given by the nationalist leader, Totius, to the 1944 volkskongres on racial policy. Here, racial separation was justified by reference to scriptural injunction, the historical experience of Afrikanerdom and the authority of science. Each of these categories is then analysed with respect to the way in which the concept of race was understood and articulated.

The paper argues that both scientific racism and distinctive forms of cultural relativism were used to justify racial separation. This depended on the fact that the categories of race, language and culture were used as functionally interdependent variables, whose boundaries remained fluid. In the main, and especially after the Second World War, Afrikaner nationalist ideologues chose to infer or suggest biological notions of racial superiority rather than to assert these openly. Stress on the distinctiveness of different ‘cultures’ meant that the burden of explaining human difference did not rest solely on the claims of racial science. As a doctrine, Christian-nationalism remained sufficiently flexible to adjust to changing circumstances. In practice, the essentialist view of culture was no less powerful a means of articulating human difference than an approach based entirely on biological determinism.

Access options

1 This paper forms part of a broader investigation into the ‘idea of race’ in twentieth-century South Africa. I have benefited from the comments of André du Toit, Johan Kinghorn, Hermann Giliomee and John Lazar, as well as those of the anonymous readers of the Journal. Earlier drafts of this paper were presented at seminars at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, London, and the 1990 African Studies Association conference in Baltimore. Translations from Afrikaans are my own.

2 This argument ties in with the broad, inclusive definition of racist ideology which I have adopted. This embraces both the idea of biologically determined superiority and inferiority, as well as the notion that culture is in some sense an expression of genetic constitution.

3 Fredrickson , G. M. , The Arrogance of Race: Historical Perspectives on Slavery, Racism and Social Inequality ( New Haven and London , 1988 ), 189 . Google Scholar

4 Rhoodie , N. J. and Venter , H. J. , Apartheid: A Socio-Historical Exposition of the Origin and Development of the Apartheid Idea ( Cape Town , 1960 ), 113 . Google Scholar

5 Ibid. 145.

6 du Plessis , L. J. , ‘Rasverhoudinge’, Koers (October 1933 ) Google Scholar ; du Plessis , H. , ‘Assimilasie of algehele segregasie’, Koers (June 1935 ). Google Scholar The latter article made a strong case for total separation (though without using the term ‘apartheid’), as opposed to the ‘neoliberalism’ of Brookes, Rheinallt Jones and Macmillan which was inevitably assimilationist. It also purported to show that racial diversity was biologically and historically determined by God.

7 Rhoodie , and Venter , , Apartheid , 170 . Google Scholar The Bond lasted for a brief time only. Its first chair was Mrs E. G. Jansen, wife of the Minister of Native Affairs from 1929 to 1933 and 1948 to 1950. The secretary was M. D. C. de Wet Nel who served as Minister of Bantu Administration from 1958 to 1961.

8 Rhoodie , and Venter , , Apartheid , 171 –2. Google Scholar Hexham documents an even earlier use of ‘apartheid’ in the context of a lecture on Calvinism at Potchefstroom in 1914. See Hexham , I. , The Irony of Apartheid ( New York and Toronto , 1981 ), 188 . Google Scholar

9 Pelzer , A. N. , Die Afrikaner-Broederbond: Eerste 50 Jaar ( Cape Town , 1979 ), 163 –4. Google Scholar Given the close links between the Broederbond and the Bond vir Rassestudie it is quite possible that the Bond's pronouncement of ‘apartheid’ after 1935 stemmed from the Broederbond's 1933 document. This may also account for the ‘definite lead’ taken by the Cape nationalist organ, Die Burger , from 1933 in rethinking Hertzogite segregation. See Rhoodie , and Venter , , Apartheid , 145 . Google Scholar

10 Kinghorn , J. . ‘The theology of separate equality: a critical outline of the DRC's position on apartheid’, in Prozesky , M. (ed.), Christianity Amidst Apartheid: Selected Perspectives on the Church in South Africa ( London , 1990 ), 58 –9. Google Scholar

11 du Plessis , J. , ‘Colonial progress and countryside conservatism: an essay on the legacy of van der Lingen of Paarl, 1831–1875’ (MA thesis, University of Stellenbosch , 1988 ) Google Scholar ; du Toit , A. , ‘The Cape Afrikaner's failed liberal moment, 1850–1870’, in Butler , J. et al. (eds.), Democratic Liberalism in South Africa ( Middletown, Connecticut and Cape Town , 1987 ). Google Scholar

12 du Plessis , J. (convenor), The Dutch Reformed Church and the Native Problem ( Stellenbosch , 1921 ). Google Scholar

13 Borchardt , C. , ‘Die “swakheid van sommige” en die sending’, in Kinghorn , J. (ed.), Die NG Kerk en Apartheid ( Johannesburg , 1986 ), 80 . Google Scholar

14 Du Plessis , , The Dutch Reformed Church , 20 , 12 . Google Scholar

15 Ibid. 11.

16 The mechanics and ideology of segregation are explored at length in my book Racial Segregation and the Origins of Apartheid in South Africa 1919–36 ( London , 1989 ). Google Scholar

17 The Dutch Reformed Church Federal Council hosted the conferences of 1923 and 1927. Subsequent conferences were organized by the South African Institute of Race Relations.

18 Karis , T. and Carter , G. M. , From Protest to Challenge ( 4 vols.) ( Stanford , 1972 – 1977 ), i , 232 . Google Scholar This resolution was proposed by Edgar Brookes. It is not clear whether it was formally adopted by the conference.

19 Kinghorn , , Die NG Kerk , 90 . Google Scholar

20 Cape Times , 3 Feb. 1927.

21 Union Government, SC 10–'27, Report of the Select Committee on the Subject of the Union Native Council Bill, Coloured Persons Rights Bill, Representation of Natives in Parliament Bill, and Natives Land (Amendment) Bill (1927), 359. See also 347ff.

22 Borchardt , , ‘Die “swakheid van sommige”’, 82 . Google Scholar

23 Loubser , J. A. , The Apartheid Bible ( Cape Town , 1987 ), 27 –8 Google Scholar ; Moodie , T. D. , The Rise of Afrikanerdom ( Berkeley and London , 1975 ), 62 . Google Scholar

24 Kinghorn , , Die NG Kerk , 87 – 90 Google Scholar ; Loubser , , The Apartheid Bible , 29 – 31 . Google Scholar

25 Kinghorn , , Die NG Kerk , 90 . Google Scholar

26 Moodie , , The Rise of Afrikanerdom , 154 . Google Scholar W. A. de Klerk comments on the basis of his personal experience: ‘Of these Diederichs spoke in words of passionate oratory, Meyer in blunter, but equally effective, rhetoric. Cronjé, in a dry-as-dust style, expounded the most thorough-going analysis of the new political sociology with deep theological overtones.’ See his The Puritans in Africa (London, 1975 ), 203 . Google Scholar

27 Bloomberg , C. , Christian-Nationalism and the Rise of the Afrikaner Broederbond in South Africa 1918–48 ( London , 1990 ), 122 . CrossRef Google Scholar

28 Inspan (Oct. 1944), 21.

30 See Bloomberg , , Christian-Nationalism , 105 –7 Google Scholar ; Loubser , , The Apartheid Bible , 35 –8. Google Scholar

31 Loubser , , The Apartheid Bible , 53 –4. Google Scholar

32 The full address is published in Inspan (Dec. 1944).

33 The term is Loubser's.

34 Inspan (Dec. 1944), 7–11.

35 Ibid. 13.

36 Badenhorst , F. G. , Die Rassevraagstuk veral Betreffende Suid-Afrika in die Lig van die Gereformeerde Etiek ( Amsterdam , 1939 ). Google Scholar Discussion here is largely focused on the different European races.

37 Kuyper's ideas were first brought to South Africa by Totius' father, S. J. du Toit, who was chiefly responsible for creating the first Afrikaans Language Movement of the 1870s and 80s.

38 This discussion of Kuyper has been drawn from Kinghorn, Die NG Kerk ; Moodie, The Rise of Afrikanerdom ; Loubser, The Apartheid Bible ; Hexham, The Irony of Apartheid.

39 See Kinghorn , , Die NG Kerk , 62 Google Scholar ; Schutte , G. J. , ‘ The Netherlands, cradle of apartheid? ’, Ethnic and Racial Studies , X ( 1987 ) Google Scholar ; Giliomee , H. and Schlemmer , L. , From Apartheid to Nation-Building ( Oxford , 1989 ), 43 –4. Google Scholar

40 Bloomberg , , Christian-Nationalism , 9 . Google Scholar

41 Kuyper , A. , Calvinism. Six Stone Lectures ( 1898 ), 37 –8 Google Scholar ; Kuyper , A. , The South African Crisis ( London , 1898 ), 24 . Google Scholar

42 Bloomberg , , Christian-Nationalism , 8 . Google Scholar

43 Moodie , , The Rise of Afrikanerdom , 154 Google Scholar ; Schutte , , ‘The Netherlands’, 412 , n. 22. Google Scholar The philosopher J. G. Herder (1744–1803) is widely regarded as the first European thinker to articulate a comprehensive philosophy of nationalism. He was responsible for developing the idea of nationality in terms of a cultural organism sharing common features—principally language. Herder's conception of culture was relativistic and was not defined in terms of race. J. G. Fichte (1762–1814) gave Herder's essentially humanistic and pluralist view a more exclusivist and narrow political emphasis by concentrating on the historical mission of the German people. He has also been seen as an early progenitor of the Fuehrer concept.

44 Kinghorn , , Die NG Kerk , 66 –8. Google Scholar

45 Proctor , R. , Racial Hygiene: Medicine Under the Nazis ( Cambridge, Mass. , 1988 ), ch. 8. Google Scholar

46 The organic metaphor of society was also stressed by the evolutionist tradition of thought which, in the guise of Social Darwinism, was used to endorse the survival of the fittest (whether constituted as individuals or aggregates of individuals).

47 Moodie , , The Rise of Afrikanerdom , 159 –60 Google Scholar ; Schutte , , ‘The Netherlands’, 411 . Google Scholar

48 Diederichs , N. J. , Nasionalisme as Lewensbeskouing en sy Verhouding tot Internasionalisme ( Bloemfontein , 1936 ) Google Scholar ; De Klerk , , Puritans in Africa , 204 . Google Scholar

49 Diederichs , , Nasionalisme as Lewensbeskouing , 24 , 17 . Google Scholar

50 Ibid. 22–3.

51 Ibid. 37.

52 Ibid. 31.

53 Vorster , J. D. , ‘ Die Kleurverskil en Kleureerbiediging ’, Koers (Feb., 1939 ), 11 , 15 , 17 . Google Scholar

54 Vorster , J. D. , ‘ Etniese verskeidenheid, kerklike pluriformiteit en die ekumene ’, in Grense (Stellenbosch, 1961 ), 65 –9. Google Scholar

55 du Preez , A. B. , Inside the South African Crucible ( Cape Town and Pretoria , 1959 ), 41 . Google Scholar (Simultaneously published in Afrikaans as Eiesoortige Ontwikkeling tot Volksdiens ). For du Preez's biblical justifications for apartheid see his Die Skriftuurlike Grondslag vir Rasseverhoudinge (Cape Town, 1955 ). Google Scholar

56 The complex process according to which theological justifications for apartheid were formulated and endorsed by the DRC is discussed in detail by Loubser, The Apartheid Bible , and Kinghorn, Die NG Kerk.

57 I owe this point to André du Toit.

58 In 1956 the Federal Council of the DRC decided: ‘The Dutch Reformed Church accepts the unity of the human race, which is not annulled by its diversity. At the same time the Dutch Reformed Church accepts the natural diversity of the human race, which is not annulled by its unity.’ See DRC, The Dutch Reformed Churches in South Africa and the Problem of Race Relations (n.d. [1956]), 13. The apartheid bible finally emerged in its most sophisticated and definitive form as Human Relations and the South African Scene in the Light of Scripture , and was presented to the DRC General Synod in 1974. This landmark document demonstrates a sensitivity to criticisms of apartheid by declaring itself opposed to racial injustice and discrimination. The concept of race itself is avoided through the use of its surrogate term—nation. Nevertheless, the concept of separate development is endorsed in terms of the ethnic diversity willed by God in His creation ordinances.

59 Loubser , , The Apartheid Bible , 53 , 71 –3. Google Scholar

60 Marais , B. J. , Colour: Unsolved Problem of the West ( Cape Town , 1952 ), 24 , n. 18. Google Scholar

61 Ibid. 295.

62 Ibid. 295.

63 Ibid. 298 [emphasis in original].

64 Cited in Loubser , , The Apartheid Bible , 74 . Google Scholar See also Keet , B. B. , Suid-Afrika—Waarheen ? ( Stellenbosch , 1955 ). Google Scholar

65 Ibid. 75. For an illuminating discussion of the interventions by Marais and Keet in the context of Afrikaner church policy, see Lazar , J. , ‘Conformity and conflict: Afrikaner nationalist politics in South Africa, 1948–1961’ (D.Phil. thesis, Oxford University , 1987 ), ch. 6. Google Scholar

66 du Preez , A. B. , Die Skriftuurlike Grondslag , 26 . Google Scholar

67 This point is developed by Kinghorn , , Die NG Kerk , 8 – 9 . Google Scholar

68 For example, Thompson , L. , The Political Mythology of Apartheid ( New Haven , 1985 ). Google Scholar

69 du Toit , A. , ‘ No chosen people: the myth of the Calvinist origin of Afrikaner nationalism and racial ideology ’, Amer. Hist. Rev. , LXXXVIII ( 1983 ), 920 –52. CrossRef Google Scholar

70 On Preller, see Isabel Hofmeyr's outstanding article, ‘Popularizing history: the case of Gustav Preller’, J. Afr. Hist. , XXIX ( 1988 ), 521 –37. Google Scholar

71 Preller , G. S. , Day-Dawn in South Africa ( Pretoria , 1938 ), 149 –51 Google Scholar [my emphasis]; also published in Afrikaans as Daglemier in Suid-Afrika. Similar ideas occur in Preller's history of the trekker leader, Andries Pretorius (Johannesburg, 1937 ), 157 ff. Google Scholar

72 See their articles in the first [c. 1940] issue of the journal Rassebakens.

73 Cronjé , G. , ʻn Tuiste vir die Nageslag ( Stellenbosch , 1945 ), 9 , 22 . Google Scholar

74 Gerdener , G. B. A. , ‘ Die buiteland en die naturellevraagstuk in Suid Afrika ’, Journal of Racial Affairs , III ( 1952 ), 6 . Google Scholar

75 Eloff began his research at the University of the Witwatersrand and ultimately became head of the Department of Genetics and Breeding Studies ( Telingsleer ) at the University of the Orange Free State. A leading member of the Ossewabrandwag, he was interned at Koffiefontein during the war, where he proclaimed his ideas on eugenics to fellow inmates, including the future prime minister B. J. Vorster. I am grateful to Professor Bruce Murray and Christo Marx for this biographical information.

76 Eloff , G. , ‘Rasverbetering deur uitskakeling van minderwaardige indiwidue’, Koers (Dec. 1933 ). Google Scholar

77 Eloff , G. , ‘Drie gedagtes oor rasbiologie veral met betrekking tot Suid-Afrika’, Koers (April, 1938 ). Google Scholar

78 Eloff , G. , Rasse en Rassevermenging: Die Boervolk Gesien van die Standpunt van die Rasseleer ( Bloemfontein , 1942 ). Google Scholar The editors of this series were J. de W. Keyter, N. Diederichs, G. Cronjé, and P. J. Meyer.

79 Ibid. foreword and 104.

80 Ibid. 51–6.

81 Ibid. 61.

82 Ibid. 26.

83 Ibid. 75–6.

84 Ibid. 76ff. For a discussion of Fischer in the context of the German race hygiene movement, see Proctor, Racial Hygiene , 40ff. See also Fischer , E. , Die Rehebother Bastards und das Bastardierungs Probleem bein Menschen ( Jena , 1913 ). Google Scholar

85 Eloff , , Rasse en Rassevermenging , 87 . Google Scholar

86 Ibid. 101.

87 Theal , G. M. , History of the Boers in South Africa ( London , 1887 ), 59 – 60 Google Scholar ; Pratt , A. , The Real South Africa ( London , 1913 ), 82 , 89 Google Scholar ; Burton , J. T. , Who are the Afrikaners ? ( Cape Town , 1927 ). Google Scholar

88 Keane , A. H. , The Boer States: Land and People ( London , 1900 ). Google Scholar

89 Ibid. 145, 161–2, 189–90.

90 du Plessis , L. J. , Problems of Nationality and Race in Southern Africa ( London , 1949 ), 6 . Google Scholar

91 Cronjé , , ʼn Tuiste vir die Nageslag: Afrika Sonder die Asiaat ( Johannesburg , 1946 ) Google Scholar ; Regverdige Rasse-Apartheid (Stellenbosch, 1947 ) Google Scholar ; Voogdyskap en Apartheid (Pretoria, 1948 ). Google Scholar

92 Cronjé , , ʼn Tuiste vir die Nageslag , 12 – 19 . Google Scholar I have discussed the topic of intelligence testing in greater detail elsewhere.

93 Cronjé , , Regverdige Rasse-Apartheid , 75 –8. Google Scholar

94 du Toit , A. , ‘Political control and personal morality’, in Schrire , R. (ed.), South Africa: Public Policy Perspectives ( Cape Town , 1982 ), 63 . Google Scholar

95 Cronjé , , ʼn Tuiste vir die Nageslag , 74 . Google Scholar

96 Ibid. 31.

97 The term ‘visionary’ was coined by John Lazar. My analysis of SABRA is influenced by the discussion of this organization in his thesis, ‘Conformity and conflict’.

98 Gerdener , G. B. A. , ‘ Die buiteland en die naturellevraagstuk in Suid Afrika ’, Journal of Racial Affairs , III ( 1952 ), 5 – 6 . Google Scholar

99 Ibid. 6.

100 Bruwer , J. P. , ‘ Prof. Dr. G. B. A. Gerdener: Ons huldig sy leierskap en sy lewe ’, Journal of Racial Affairs , VII ( 1956 ), 51 . Google Scholar

101 Eiselen , W. M. M. , ‘ Ons Jeug en ons rasse-aangeleenthede ’, Journal of Racial Affairs , IV ( 1953 ). Google Scholar

102 Eiselen , W. M. M. , Die Naturelle-Vraagstuk ( Cape Town , 1929 ). Google Scholar

103 See Eiselen's foreword to Fick's , M. L. The Educability of the South African Native ( Pretoria , 1939 ), iv Google Scholar ; Union Government (UG 53/1951), Report of the Commission on Native Education 1949–1951 , 13, para. 60. But note the dissentient remarks of A. H. Murray, 165, para. 2.

104 Eiselen , W. M. M. , ‘ Is separation practicable? ’, Journal of Racial Affairs , 1 ( 1950 ), 18 . Google Scholar

105 Olivier , N. J. J. , ‘ Apartheid—a slogan or a solution? ’, Journal of Racial Affairs , VI ( 1954 ), 24 –5. Google Scholar

106 Union Government, (UG 61–1955), Summary of the Report of the Commission for the Socio-Economic Development of the Bantu Areas within the Union of South Africa ( 1955–6 ), 2, para. 12. In the full seventeen-volume Tomlinson Report, which is untranslated and available only in mimeograph form, the race paradigm is even more strongly evident. So is the academic basis from which the distilled conclusions of the published version are drawn.

107 Ibid. 9, para. 71.

108 Ibid. 20, para. 20.

109 Coetzee , J. Albert , Nasie-Wording in Suid Afrika: ʼn Sleutel vir die Politieke Probleem van Suid Afrika ( Potchefstroom , 1931 ). Google Scholar

110 du Toit , S. , ‘Openbaringslig op die apartheidsvraagstuk’, Koers ( 08 1949 ), 14 . Google Scholar

111 Bruwer , J. P. , ‘ Grondbeginsels i.v.m. fisiese en kulturele verskille ’, Journal of Racial Affairs , IV ( 1953 ), 41 –2 Google Scholar ; Verslag van die Kommissie vir die Sosio-Ekonomiese Ontwikkeling van die Bantoegebiede Binne die Unie van Suid-Afrika , vol. 1, 67, para. 122.

112 Eloff , , Rasse en Rassevermenging , 26 , 27 . Google Scholar

113 Kinghorn , , ‘The theology of separate equality’, 67 . Google Scholar

114 For example, the assumption that language and culture were expressions of race was an essential element in post-Enlightenment anthropological thought. Similarly, the notion that non-physical characteristics (e.g. culture) are capable of absorption and transmission from one generation to the next derives in large part from Lamarck's theory of the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

115 O'Meara , D. , Volkskapitalisme: Class, Capital and Ideology in the Development of Afrikaner Nationalism, 1934–48 ( Cambridge , 1983 ). Google Scholar

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 33, Issue 2

- Saul Dubow (a1)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853700032217

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

The rise of Afrikaner and African Nationalism Essay Grade 11 Guide

On this page you will read about “The rise of Afrikaner and African Nationalism”, which will significantly assist you as a guide when you prepare for your Grade 11 History. On this page, most of the key events and crucial points are presented.

Also read: The social and economic impact brought about by the natives land act of 1913

Afrikaner and African Nationalism Grade 11 Essay Key Points

British colonies in south africa.

- No South Africa before 1910

- Britain defeated Boer Republics in South African War (1899–1903)

- Four separate colonies: Cape, Natal, Orange River, Transvaal colonies(which are ruled by Britain and needed support of white settlers in colonies to retain power).

Union of South Africa

- In 1908, 33 white delegates met behind closed doors to negotiate independence for Union of South Africa

- Views of 85% of country’s future citizens (black people) not even considered.

- British wanted investments protected, labour supplies assured: agreed to give political/economic power to white settlers

- Union Constitution of 1910 placed political power in hands of white citizens

Cape Province

- small number of educated black, coloured citizens allowed to elect few representatives to Union parliament

- only whites had vote

- settler nation’ = no room for blacks with rights

- white citizens called selves ‘Europeans’

- all symbols of new nation = European, e.g. language, religion, school history

- African languages, histories, culture seen as inferior

Racism in the new nation:

- could practise traditions in ‘native’ reserves

- in settler (white) nation = required only as workers in farms, mines, factories owned by whites

- black people denied political rights, cultural recognition, economic opportunities.

1910 → large numbers of black South African men forced to become migrant workers on mines, factories, expanding commercial farms.

1913 Natives Land Act → worsened situation: land allocated to black people by Act = largely infertile, unsuitable for agriculture.

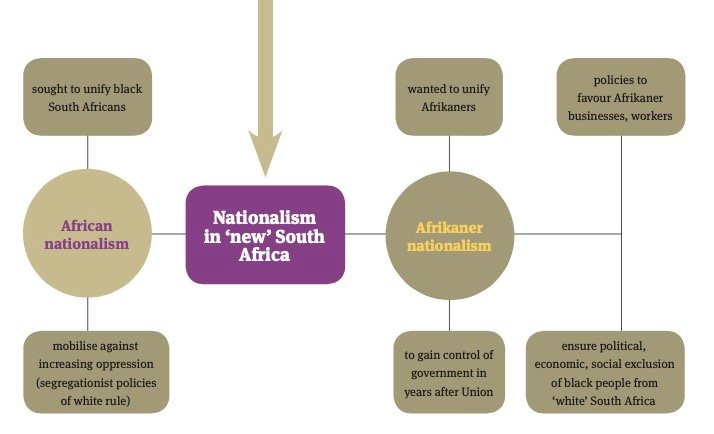

Land Act, segregation policies (including in work and economy) and World economic depressions (Great Depression that started in USA) resulted in forced migration of people (blacks and white) in South Africa in the 1920s, 30s, 40s. 1 000s of poor white + black tenant farmers forced off land, into cities: – some = domestic workers/worked in industry – did not have such strong ties to old rural/ethnic identities – two forms of nationalism emerged in SA: African Nationalism and Afrikaner Nationalism

View all Grade 11 History Study Resources here

A Guide on How to Write the Rise of Afrikaner and African Nationalism Essay

To write an essay on the rise of Afrikaner and African Nationalism, follow these steps:

- Introduction:

- Provide a brief overview of the historical context leading up to the rise of Afrikaner and African Nationalism.

- Introduce the British colonies in South Africa, the South African War, and the Union of South Africa.

- British Colonies in South Africa:

- Explain the situation in South Africa before 1910, when there was no unified South Africa.

- Discuss the outcome of the South African War and the formation of the four separate colonies (Cape, Natal, Orange River, Transvaal).

- Formation of the Union of South Africa:

- Describe the process that led to the creation of the Union of South Africa, including the 1908 meeting of white delegates.

- Explain how the views of the black majority were ignored and how political and economic power was given to white settlers.

- Union Constitution and Cape Province:

- Discuss the Union Constitution of 1910, which placed political power in the hands of white citizens.

- Talk about the situation in the Cape Province, where a small number of educated black and colored citizens could elect a few representatives to the Union parliament.

- The New Nation:

- Describe how the new nation was a ‘settler nation’ with no room for blacks with rights.

- Discuss how the symbols of the new nation were European, including language, religion, and school history.

- Mention the treatment of African languages, histories, and culture as inferior.

- Racism and its Effects:

- Explain how Africans were viewed as members of inferior ‘tribes’ and were limited to practicing traditions in ‘native’ reserves.

- Discuss the denial of political rights, cultural recognition, and economic opportunities for black people.

- Explain the consequences of this racism, such as the forced migration of black South African men to work as migrant workers in mines, factories, and commercial farms.

- 1913 Natives Land Act:

- Discuss the impact of the 1913 Natives Land Act on the allocation of land to black people.

- Describe how the Act worsened the situation by allocating infertile, unsuitable land for agriculture.

- Migration and the Emergence of Nationalism:

- Explain how the Land Act, segregation policies, and the Great Depression led to forced migration in South Africa.

- Discuss the consequences of this migration for both black and white populations.

- Explain how this migration led to the emergence of African Nationalism and Afrikaner Nationalism.

- Conclusion:

- Summarize the main points of the essay, highlighting the rise of Afrikaner and African Nationalism in response to the historical context and events discussed.

- End the essay by discussing the ongoing impact of these nationalisms on South Africa’s history and present-day situation.

Remember to use the information provided as a basis for your essay, but also to conduct further research on the topic to provide a comprehensive understanding of the rise of Afrikaner and African Nationalism.

More sources

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1MRbTttLwBHFDOOinecTp2U5G12pP7DtbGjgiAElkP3w

https://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/book-4-industrialisation-rural-change-and-nationalism-chapter-3-afrikaner-nationalism-1930s

The social and economic impact brought about by the natives land act of 1913

Looking for something specific?

Leave a comment.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

You May Also Like

Violation of Human Rights in South Africa: A Dark Decade (1950-1960)

Grade 11 History Essays Topics for Term 3

Reasons Why the District Six Museum is so Famous?

History grade 11 june 2023 exam question papers with the memorandums pdf download.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Gr. 11 History T3 W4: The Rise of Afrikaner Nationalism

The Rise of Afrikaner Nationalism - Economic affirmative action in the 1920's and 1930's

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.

Home Contact us Terms of Use Privacy Policy Western Cape Government © 2024. All rights reserved.

Afrikaner Nationalism Essay For Students in English

Table of Contents

Introduction

Assuring and preserving Afrikaner interests was the primary objective of the National Party (NP) when it was elected to power in South Africa in 1948. After the 1961 Constitution, which stripped black South Africans of their voting rights, the National Party maintained its control over South Africa through outright Apartheid.

Hostility and violence were common during the Apartheid period. Anti-Apartheid movements in South Africa lobbied for international sanctions against the Afrikaner government following the Sharpeville Massacre of 1960, which resulted in the deaths of 69 black protestors (South African History Online).

Apartheid was not adequately representing the interests of Afrikaners, according to many Afrikaners who questioned the NP’s commitment to maintaining it. South Africans refer to themselves as Afrikaners both ethnically and politically. Boers, which means ‘farmers,’ were also referred to as Afrikaners until the late 1950s.

Afrikaner Nationalism Essay Full Essay

Although they have different connotations, these terms are somewhat interchangeable. The National Party represented all South African interests prior to Apartheid as a party opposing British imperialism. Therefore, nationalists sought complete independence from Britain not just politically (White), but also economically (Autarky) and culturally (Davenport).

Afro-African, black, colored, and Indian were the four main ethnic groups in South Africa during this time period. At the time, the ruling class was made up of white people who spoke Afrikaans: they claimed blacks and coloreds were brought over for work involuntarily during settler-colonialism, so they did not have a history or culture. Therefore, Afrikaner nationalism served as a preservationist ideology (Davenport) for the white heritage.

South African History

Increasing participation of Indian people in government and politics indicates that Afrikaner nationalism is becoming more inclusive as Indians are recognized as South Africans.

During Apartheid, white South Africans spoke Afrikaans, a language derived from Dutch. As an official language of South Africa, Afrikaner has become an increasingly common term to describe both an ethnic group and its language.

The Afrikaans language was developed by the poor white population as an alternative to the standard Dutch language. Afrikaans was not taught to black speakers during Apartheid, which resulted in it being renamed Afrikaner instead of Afrikaans.

The Het Volk party (Norden) was founded by D.F. Malan as a coalition among Afrikaner parties, such as the Afrikaner bond and Het Volk. The United Party (UP) was formed by J.B.M. Hertzog in 1939 after he broke away from his more liberal wing to form three consecutive NP governments from 1924 to 1939.

Black South Africans were lobbied successfully for more rights during this period by the opposition United Party, which eliminated racial segregation into separate spheres of influence known as Grand Apartheid, which meant whites could control what blacks did in their segregated neighborhoods (Norden).

National Party

South Africans were classified into racial groups based on their appearance and socio-economic status under the Population Registration Act enacted by the NP after defeating the United Party in 1994. In order to build a strong base of support for its political party, the NP joined forces with the Afrikanerbond and Het Volk.

It was founded in 1918 to address inferiority complexes created by British imperialism (Norden) among Afrikaners by “ruling and protecting” them. It was exclusively white people who joined the Afrikaner bond since they were only interested in shared interests: language, culture, and political independence from the British.

Afrikaans was officially recognized as one of the official languages of South Africa in 1925 by the Afrikaner bond, which established the Afrikaanse Taal-en Kultuurvereniging. Also, the NP began supporting cultural activities such as concerts and youth groups in order to bring Afrikaners under one banner (Hankins) and mobilize them into a cultural community.

There were factions within the National Party that were based on socioeconomic class differences, rather than being a monolithic body: some members recognized that they needed more grassroots support to win the 1948 elections.

You may also read below mentioned other essays from our website for free,

Essay on Bantu Education Act In English For Free

- Essay on Education Goals In English

Afrikaner Nation

By promoting Christian nationalism to South Africans, the National Party encouraged citizens to respect rather than fear their differences, thus gaining votes from Afrikaners (Norden). The ideology could be considered racist since no equality was recognized between races; rather, it advocated controlling the region assigned to blacks without integrating them into other groups.

As a result of Apartheid, black and white residents were segregated politically and economically. Because whites could afford better housing, schools, and travel opportunities, segregation became an institutionalized socioeconomic system that favored rich whites (Norden).

By gaining the Afrikaner population vote in 1948, the National Party slowly came to power despite early opposition to Apartheid. They officially established Apartheid one year after winning the election, as a federal law allowing white South Africans to participate in political representation without the right to vote (Hankins).

In the 1950s, under Prime Minister Dr. NP, this harsh form of social control was implemented. By replacing English with Afrikaans in schools and government offices, Hendrik Verwoerd paved the way for the development of an Afrikaner culture where white people celebrated their differences rather than hid them (Norden).

A mandatory identification card was also issued by the NP to blacks at all times. Due to the lack of a valid permit, they were prohibited from leaving their designated region.

A system of social control was designed to control the black movement by white police officers, causing natives to be afraid of traveling into areas that were assigned to other races (Norden). As a result of Nelson Mandela’s refusal to submit to minority rule by whites, his ANC became involved in resistance movements against Apartheid.

Through the creation of bantustans, the nationalist movement maintained Africa’s poverty and prevented its emancipation. Despite living in a poor region of the country, southern Africa people had to pay taxes to the white government (Norden) because bantustans were lands specifically reserved for black citizens.

As part of the NP’s policies, blacks were also required to carry identity cards. In this way, police were able to monitor their movement and arrest them if they entered another race’s designated area. “Security forces” took control of townships where blacks protested unfair government treatment and were arrested or killed.

Besides being denied representation in Parliament, black citizens received significantly fewer educational and medical services than whites (Hankins). Nelson Mandela became the first president of a fully democratic South Africa in 1994 after the NP ruled apartheid-era South Africa from 1948 to 1994.

A majority of NP members were Afrikaners who believed that British imperialism had “ruined” their country after World War II due to British imperialism (Walsh). Also, the National Party used ‘Christian Nationalism’ to win Afrikaner people votes by claiming that God created the world’s races and must therefore be respected rather than feared (Norden).

Nevertheless, this ideology could be viewed as racist since it did not recognize equality between races; it merely argued that blacks should remain independent within their assigned regions rather than integrate with others. Due to the NP’s complete control over Parliament, black Citizens were not oblivious to apartheid’s unfairness but were powerless to address it.

As a result of British imperialism after the first world war, Afrikaners overwhelmingly supported the National Party. This party sought to create a separate culture where whites would have sole responsibility for government. Architect of apartheid Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd promoted intense segregation between blacks and whites during his Prime Ministership between 1948 and 1952.

The Nordics believed that differences should be embraced rather than feared because there are irreconcilable differences in which one group will always dominate. Although Hankins suggested black citizens remain in their bantustans rather than integrating with other cultures (Hankins), he failed to recognize these ‘irreconcilable’ groups as equals.

In addition to requiring blacks to carry identity cards, the NP passed laws to make them do so. The police were able to monitor their movements more easily as a result. If caught crossing into an area designated for another race, they were arrested.

Nelson Mandela was elected as South Africa’s first black president (Norden) on April 27th, 1994, marking the end of apartheid. In his speech after becoming president, Mandela explicitly stated that he had no intention of disparaging Afrikaners. He instead sought to enhance the positive aspects while reforming “the less desirable aspects of Afrikaner history” (Hendricks).

When it came to apartheid’s sins, he advocated Truth and Reconciliation rather than retribution, allowing all sides to discuss what happened without fear of punishment or retaliation.

Mandela, who helped create the new ANC government after losing the election, did not dissolve the NP but rather promoted reconciliation between Afrikaners and non-Afrikaners by bringing Afrikaner culture and traditions to the forefront of racial reconciliation.

Despite their ethnicities, South Africans were able to watch rugby games together because the sport became a unifying factor for the nation. The black Citizens who played sports watched television, and read newspapers without fear of persecution were Nelson Mandela’s hope for them (Norden).

Apartheid was abolished in 1948, but Afrikaners were not fully eliminated. While the interracial sport does not necessarily mean the NP is no longer ruling the country, it does bring hope for future South African generations to be able to reconcile with their past rather than live in fear.

South African blacks are less likely to perceive whites as oppressors because they are more involved in Afrikaner culture. Once Mandela is out of office, it will be easier to achieve peace between blacks and whites. Aiming to build better relationships between races is more important now than ever before, as Nelson Mandela will retire on June 16th, 1999.

Under Nelson Mandela’s administration, Afrikaners once again felt comfortable with their status in society because the white government was brought into the 21st century. President Jacob Zuma is almost certain to be reelected to South Africa’s top job in 2009 as the leader of the ANC (Norden).

Conclusion,

Since the NP had a plurality of power based on support from Afrikaner voters, they were able to retain control over Parliament until they lost their election; thus, whites were worried that voting for another party would lead to more power for blacks, which would lead to a loss of white privilege due to affirmative action programs if they voted for another party.

Long & Short Essay on Rainy Season in English

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

How Afrikaner identity can be re-imagined in a post-apartheid world

Associate Professor, Sociology, University of Pretoria

Disclosure statement

Christi van der Westhuizen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Pretoria provides funding as a partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

This article is a foundation essay. These are longer than usual and take a wider look at a key issue affecting society.

In a post-apartheid context, is a democratic Afrikaner identity possible? Are there other traditions apart from apartheid that can be drawn on in Afrikaner culture that can advance democracy and social justice? These questions are particularly relevant in South Africa, given that in recent years there has been a heightened contestation over Afrikaner identify, driven by a hardening of whiteness.

When the National Party came to power in 1948 politician JG Strijdom , the apartheid prime minister between 1954 and 1958 who was nicknamed the “Lion of the North”, demanded “ eendersdenkendheid ”. The Afrikaans word means a condition of thinking the same. It is a collective term as it necessarily requires more than one person to abide by it.

The directive of eendersdenkendheid was founded in apartheid . Opposition to apartheid was as treasonous as refusing to defend your country during a war, hardliner Strijdom told his white, assumed-to-be male audience.

This demand for conformism to a particular ethnic configuration of heteropatriarchal white supremacism – also known as apartheid – permeated Afrikaner nationalism. State power amplified the authoritarian tendency of conformism in Afrikanerdom. Anyone who did not bend the knee was a “ volksverraaier ”, or traitor to the volk (Afrikaner people).

A democratic Afrikaner identity

In thinking what it means to re-imagine the formerly hegemonic identity of apartheid, namely “the Afrikaner”, and what 22 years of democracy in South Africa should mean for this identity, I want to advance andersdenkendheid – a condition of thinking differently – as the democratic duty of Afrikaners.

Andersdenkendheid refers again to a collective. But it is a countervailing action against conformism in that one adopts a posture of questioning and critical thinking. One then creates a condition of thinking differently to the dominant thinking within a collective, which is literally what andersdenkendheid means.

Certain sections of white Afrikaans-speaking civil society and the media want Afrikaners to think that they all have the same beliefs. They want all Afrikaners to inherently believe that women, black people, lesbians and gays are inferior. They want all Afrikaners to feel so threatened by anyone different to what is regarded as the “norm” that everyone has to suppress their humanity.

But not all Afrikaners are like that. There were those Afrikaners who had the courage to be different, who were the volksverraaiers (traitors to the people) before South Africa’s transition to democracy in 1994. Treason in this sense meant rejecting racist and heteropatriarchal oppression and brutalisation.

They are the people who today can show Afrikaners how to once again say “not in my name” when certain organisations pretend to speak on their behalf. Or when certain media corporations pretend to represent “true Afrikaner identity”. The volksverraaiers point the way to full participation in South Africa’s democracy.

A constructed identity

Why was there such a strong emphasis on eendersdenkendheid about apartheid, to the extent that diversion amounted to volksverraad (treason)? As with all identities, Afrikanerness is constructed. It was cobbled together using race, gender, class, sexuality and, importantly, ethnicity.

Afrikanerness was a particularly precarious identity. It wedged a space where it claimed the privileges of dominant Anglo whiteness but also demanded separateness on the basis of ethnicity. However, it did not want to be lumped with black ethnic others because then it would lose the benefits of whiteness.

Therefore Afrikaner nationalism spent the first several decades of the 20th century “purifying” its members.

But seismic changes were under way that would have profound changes.

Militant women, communists and literary dissidents

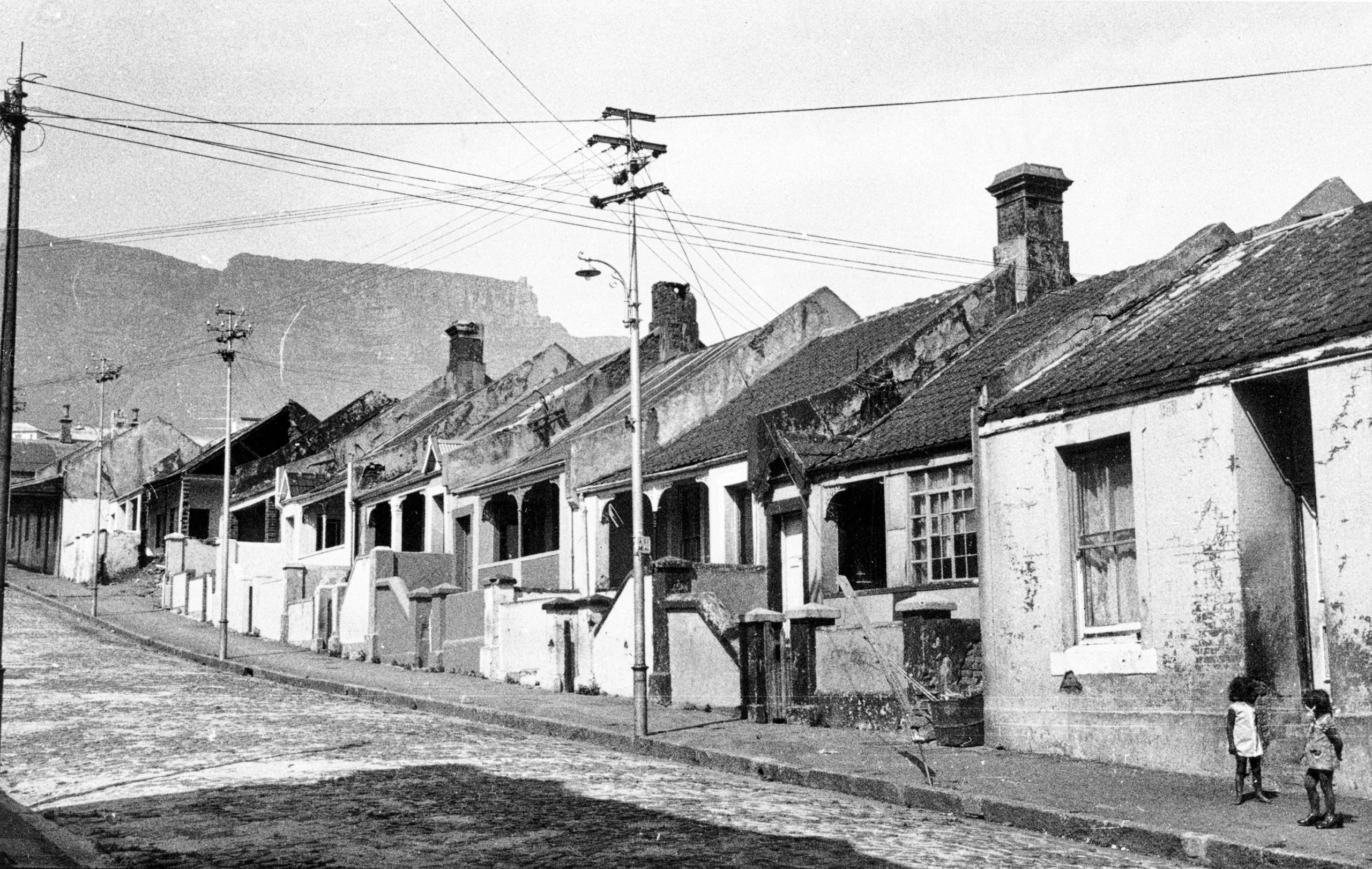

After the South African War of 1899-1902, Afrikaner nationalist cultural entrepreneurs undertook large-scale political, social and economic work to recruit individuals to their political project. This included emphasising the Afrikaans language over its Dutch predecessor. Class, gender and sexuality were used in the service of whiteness, for example, to “save” thousands of young Dutch/Afrikaans-speaking women under the guise of resolving the “poor white problem” .

These women, who went to work in Johannesburg and Pretoria, were breaking free from the patriarchal Boer family. They were mixing in the diverse communities burgeoning in the multiracial slums of the Witwatersrand. It was an intense scene of ideological battle. Afrikaner nationalism was up against socialism and liberalism.

The troublesome young women organised themselves in the Garment Workers’ Union , described as one of the most militant unions in the years between the two world wars. Leading members Hester and Johanna Cornelius , Anna Scheepers , Katie Viljoen, Dulcie Hartwell and Anna Jacobs created themselves as socialist volksmoeders (mothers of the nation). As Jacobs declared:

We shall take the lead and climb the Drakensberg again.

These socialist volksmoeders serve as a democratic pointer today.

Jacobs drew on the courage and militancy of the Boer women in the face of British imperialism. But she did so in an expansive mode of advancing equalisation. It was a proposition that was anathema to Afrikaner nationalism.

Advocate Bram Fischer similarly serves as a democratic pointer. Fischer, who was part of the legal team that presented the 90-odd accused in the Treason Trial of 1956-1961 and member of the Communist Party , came from “Afrikaner royalty”. He was prosecuted under the Suppression of Communism Act in 1966 .

From the dock Fischer quoted Paul Kruger , the Boer republic president:

With confidence we lay our case open before the whole world. Whether we conquer or whether we die: Freedom shall rise in Africa like the sun from the morning clouds.

Again, Fischer was expanding Kruger’s notion of freedom from British imperialism to a much more encompassing idea.

Fischer was sentenced to life imprisonment and subjected to daily humiliations and harsh treatment in prison.

The poet Breyten Breytenbach faced similar treatment. He had become radicalised when his Vietnamese partner Yolande was denied entry to South Africa on the basis of being “non-white” in the mid-60s. His militant organisation Okhela was short-lived. He was arrested and sentenced to seven years in jail.

In “Confessions of an Albino Terrorist” , Breytenbach describes how his Afrikaner male warden singled him out for abuse. The warden was

a complete marionette, fierce and violent. He opened my door with a brusque gesture… and said ‘Ek is die baas van die plaas [I am the boss around here]. I will make you crawl… You will get to know me yet’. Yes, I did get to know him.

These examples make a specific point. Afrikaner nationalism enforced a particularly totalitarian version of identity in which there was little room to manoeuvre for any individuals. Those who dared to transgress were heavily punished.

Writing during apartheid, author Andre Brink explained that dissidence provoked a vicious reaction from the Afrikaner establishment because it subverted apartheid. A dissident was regarded as a traitor to everything Afrikanerdom stood for, since apartheid had become everything that Afrikanerdom stood for.

In the post-apartheid conditions of a reassertion of white supremacism, the socialist volksmoeders , Fischer and Breytenbach can be used as guides. What sets these so-called traitors or volksverraaiers apart from the volk is their ability to identify with the racialised other through a sense of common humanity.

Mandela’s Poet

Ingrid Jonker , poet and daughter of a National Party politician responsible for censorship, exemplified this. Her poems include “ The child who was shot by soldiers at Nyanga ”, which was read by Nelson Mandela when he opened the first democratic parliament in 1994. Her poem “ I am with those ” features a line: “I am with those […]/ coloured African deprived.”

As the US philosopher Judith Butler reminds us:

One seeks to preserve oneself against the injuriousness of the other but if one was successful at walling oneself off from injury one would become inhuman.

The volksverraaiers lived this truth in the face of a system that dehumanised its outsiders and made its insiders inhuman.

There are again attempts to re-enforce eendersdenkendheid , to narrow down and simplify Afrikaner identities, and to corral Afrikaners into a laager with a view of the world filled with suspicion, fear and arrogance. The volksverraaiers point the way out of this inhumanity. They have done so by claiming the tradition of andersdenkendheid . With that they have provided Afrikaners with a place to build the vibrant democracy that is South Africa.

A version of this paper was first delivered at the Wits Centre for Diversity Studies’ Re-imagining Afrikaner Identities Dialogue, Johannesburg, March 10 2016.

Economics Editor

Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Indigenous Strategy and Services)

Director and Chief of Staff, Indigenous Portfolio

Chief People & Culture Officer

Lecturer / senior lecturer in construction and project management.

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

Afrikaner Nationalism

Save to my list

Remove from my list

Afrikaner Nationalism. (2016, Mar 31). Retrieved from https://studymoose.com/afrikaner-nationalism-essay

"Afrikaner Nationalism." StudyMoose , 31 Mar 2016, https://studymoose.com/afrikaner-nationalism-essay

StudyMoose. (2016). Afrikaner Nationalism . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/afrikaner-nationalism-essay [Accessed: 27 Sep. 2024]

"Afrikaner Nationalism." StudyMoose, Mar 31, 2016. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://studymoose.com/afrikaner-nationalism-essay

"Afrikaner Nationalism," StudyMoose , 31-Mar-2016. [Online]. Available: https://studymoose.com/afrikaner-nationalism-essay. [Accessed: 27-Sep-2024]

StudyMoose. (2016). Afrikaner Nationalism . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/afrikaner-nationalism-essay [Accessed: 27-Sep-2024]

- Filipino Nationalism Pages: 8 (2139 words)

- Does Nationalism Inevitably Breed Rivalry and Conflict? Pages: 3 (628 words)

- The Rise Of Nationalism In Nigeria Pages: 21 (6021 words)

- Nationalism and Sectionalism During The War of 1812 Pages: 7 (1925 words)

- Tolerance, Nationalism and Symbolic Efficiency: The Film Invictus Pages: 6 (1524 words)

- Difference between Globalism and Nationalism Pages: 5 (1481 words)

- Brahmanic Hinduism and the Rise of Hinduvata Nationalism Pages: 9 (2461 words)

- The Nationalism And Archaeology Pages: 5 (1426 words)

- Nationalism and the Concept of Imagined Communities by Benedict Anderson Pages: 6 (1560 words)

- Jose Rizal and his Nationalism Pages: 20 (5817 words)

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

History Grade 11 - Topic 4 Essay Questions

Essay Question:

To what extent were Black South Africans were deprived of their political, economic, and social rights in the early 1900s and how did this reality pave the way for the rise of African Nationalism? Present an argument in support of your answer using relevant historical evidence. [1]

Background and historical overview:

There was no South Africa (as we know it today) before 1910. Britain had defeated Boer Republics in the South African War which date from (1899–1903). There were four separate colonies: Cape, Natal, Orange River, Transvaal colonies and each were ruled by Britain. They needed support of white settlers in colonies to retain power. [2] In 1908, about 33 white delegates met behind closed doors to negotiate independence for Union of South Africa. The views and opinions of 85% of country’s future citizens (black people) not even considered in these discussions. British wanted investments protected, labour supplies assured, and agreed on the fundamental question to give political/economic power to white settlers. [3] This essay pushes back in time to analyse how this violent context in South African history served as an ideological backdrop for the rise of African nationalism in the country and elsewhere in the world.

The Union Constitution of 1910 placed political power in hands of white citizens. However, a small number of educated black, coloured citizens allowed to elect few representatives to Union parliament. [4] More generally, it was only whites who were granted the right to vote. They imagined a ‘settler nation’ where was no room for blacks with rights. In this regard, white citizens called selves ‘Europeans’. Furthermore, all symbols of new nation, European language (mainly English and Dutch), religion, school history. In this view, African languages, histories, culture were portrayed as inferior. [5]

Therefore, racism was an integral feature in colonial societies, and this essentially meant that Africans were seen as members of inferior ‘tribes’ and thus should practise traditions in ‘native’ reserves. Whilst, on the other hand, in the settler (white) nation, black people were recognized only as workers in farms, mines, factories owned by whites. Thus, black people were denied of their political rights, cultural recognition, economic opportunities, because of these entrenched processes and politics of exclusion. In 1910 large numbers of black South African men were forced to become migrant workers on mines, factories, expanding commercial farms. In 1913, the infamous Natives Land Act, worsened the situation for black people as land allocated to black people by the Act was largely infertile and unsuitable for agriculture. [6]

Rise of African Nationalism:

In the 19th century, the Western-educated African, coloured, Indian middle class who grew up mainly in the Cape and Natal, mostly professional men (doctors, lawyers, teachers, newspaper editors) and were proud of their African, Muslim, Indian heritage embraced idea of progressive ‘colour-blind’ western civilisation that could benefit all people. This was a more worldly outlook or form of nationalism which recognized all non-white groupings across the colonial world as victims of colonial racism and violence. [7] However, another form of nationalism recognized the differences within the colonized groups and argued for a stricter and more specific definition of what it means to be African in a colonial world. These were some differences within the umbrella body of African nationalism and were firmly anchored during the course of the 20th century.

African Peoples’ Organization:

One of the African organisations that led to the rise of African nationalism was the African People’s Organisation (APO). At first the APO did not concern itself with rights of black South Africans. They committed themselves to the vision that all oppressed racial groups must work together to achieve anything. Therefore, a delegation was sent to London in 1909 to fight for rights for coloured (‘coloured’. In this context, ‘everyone who was a British subject in South Africa and who was not a European’). [8]

Natal Indian Congress:

Natal Indian Congress Natal Indian Congress (NIC) was an important influence in the development of non-racial African nationalism in South Africa. Arguably, it was one of the first organisations in South Africa to use word ‘congress’. It was formed in 1894 to mobilise the Indian opposition to racial discrimination in Colony. [9] The founder of this movement was MK Gandhi who later spearheaded a massive peaceful resistance (Satyagraha) to colonial rule. This protest forced Britain to grant independence to India, 1947. The NIC organised many protests and more generally campaigned for Indian rights. In 1908, hundreds of Indians gathered outside Johannesburg Mosque in protest against law that forced Indians to carry passes, passive resistance campaigns of Gandhi and NIC succeeded in Indians not having to carry passes. But, however, they failed to win full citizenship rights as the NIC did not join united national movement for rights of all citizens until 1930s, 1940s

South African Native National Congress (now known as African National Congress):

In response to Union in 1910, young African leaders (Pixley ka Isaka Seme, Richard Msimang, George Montsioa, Alfred Mangena) worked with established leaders of South African Native Convention to promote formation of a national organization. The larger aim was to form a national organisation that would unify various African groups. [10] On 8 January 1912, first African nationalist movement formed at a meeting in Bloemfontein. South African National Natives Congress (SANNC) were mainly attended by traditional chiefs, teachers, writers, intellectuals, businessmen. Most delegates had received missionary education. They strongly believed in 19th century values of ‘improvement’ and ‘progress’ of Africans into a global European ‘civilisation’ and culture. In 1924, the SANNC changed name to African National Congress (ANC), in order to assert an African identity within the movement. [11]

Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU):

The Industrial and Commercial Workers Union African protest movements that helped foster growing African nationalism in early 1920s . Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU) was formed in 1919 was led by Clements Kadalie, Malawian worker. This figure had led successful strike of dockworkers in Cape Town. Mostly active among farmers and migrant workers. But, only temporarily away from their farms and was very difficult to organise. The central question to pose is to examine the ways in which the World War II influence the rise of African nationalism? Essentially, there were various ways that WW II influenced the rise of African nationalism. [12] Firstly, through the Atlantic Charter, AB Xuma’s, African claims in relation to this Charter. In addition, the influence of politicized soldiers returning from War had a significant impact.

The Atlantic Charter and AB Xuma’s African claims Churchill and Roosevelt issued the Atlantic Charter in 1941, describing the world they would like to see after WWII. To the ANC and African nationalists generally, the Atlantic Charter amounted to promise for freedom in Africa once war was over. Britain recruited thousands of African soldiers to fight in its armies (nearly two million Africans recruited as soldiers, porters, scouts for Allies during war). This persuaded Africans to sign up and Britain called it ‘a war for freedom’. [13] The soldiers returning home expected Britain to honour their sacrifice, however, the recognition they expected did not arrive and thus became bitter, discontented, and only had fought to protect interests of colonial powers only to return to exploitation and indignities of colonial rule.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this essay has attempted to examine the historical circumstances in which black people were denied of their political, economic, and social rights in the early 1990s. There are various that must be acknowledged in order to have a granular understanding of the larger and longer history of African nationalism, and this examination may exceed the scope of this essay. However, the central argument made here is that the rise of African nationalism in all its different ethos and manifestations was premised on humanizing black people in various parts of the colonial world. To stress this point, African nationalism emerged as a vehicle of resistance and humanization. Finally, African nationalism cannot be read outside the international context (as shown throughout the paper), as we have to take into account various factor which effectively influenced the spurge of this ideological outlook in society.

This content was originally produced for the SAHO classroom by Ayabulela Ntwakumba & Thandile Xesi.

[1] National Senior Certificate.: “Grade 11 November 2019 History Paper 2 Exam,” National Senior Certificate, November 2019. Eastern Cape Province Education.

[2] Williams, Donovan. "African nationalism in South Africa: origins and problems." The Journal of African History 11, no. 3 (1970): 371-383.

[3] Feit, Edward. "Generational Conflict and African Nationalism in South Africa: The African National Congress, 1949-1959." The International Journal of African Historical Studies 5, no. 2 (1972): 181-202.

[4] Chipkin, Ivor. "The decline of African nationalism and the state of South Africa." Journal of Southern African Studies 42, no. 2 (2016): 215-227.

[5] Prinsloo, Mastin. "‘Behind the back of a declarative history’: Acts of erasure in Leon de Kock's Civilizing Barbarians: Missionary narrative and African response in nineteenth century South Africa." The English Academy Review 15, no. 1 (1998): 32-41.

[6] Gilmour, Rachael. "Missionaries, colonialism and language in nineteenth‐century South Africa." History Compass 5, no. 6 (2007): 1761-1777.

[7] Lester, Alan. Imperial networks: Creating identities in nineteenth-century South Africa and Britain. Routledge, 2005.

[8] Van der Ross, Richard E. "The founding of the African Peoples Organization in Cape Town in 1903 and the role of Dr. Abdurahman." (1975).

[9] Vahed, Goolam, and Ashwin Desai. "A case of ‘strategic ethnicity’? The Natal Indian Congress in the 1970s." African Historical Review 46, no. 1 (2014): 22-47.

[10] Suttner, Raymond. "The African National Congress centenary: a long and difficult journey." International Affairs 88, no. 4 (2012): 719-738.

[11] Houston, G. "Pixley ka Isaka Seme: African unity against racism." (2020).

[12] Xuma, A. B. "African National Congress invitation to emergency conference of all Africans."

[13] Kumalo, Simangaliso. "AB Xuma and the politics of racial accommodation versus equal citizenship and its implication for nation-building and power-sharing in South Africa."

- Bennett-Smyth, T., 2003, September. Transcontinental Connections: Alfred B Xuma and the African National Congress on the World Stage. In workshop on South Africa in the 1940s, Southern African Research Centre, Kingston, Canada.

- Chipkin, I., 2016. The decline of African nationalism and the state of South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 42(2), pp.215-227.

- Feit, E., 1972. Generational Conflict and African Nationalism in South Africa: The African National Congress, 1949-1959. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 5(2), pp.181-202.

- Kumalo, S., AB Xuma and the politics of racial accommodation versus equal citizenship and its implication for nation-building and power-sharing in South Africa.

- Moeti, M.T., 1982. ETHIOPIANISM: SEPARATIST ROOTS OF AFRICAN NATIONALISM IN SOUTH AFRICA.

- Rotberg, R., "African nationalism: concept or confusion?." The Journal of Modern African Studies 4, no. 1. pp. 33-46.

- Swan, M., 1984. The 1913 Natal Indian Strike. Journal of Southern African Studies, 10(2), pp.239-258.

- Vahed, G. and Desai, A., 2014. A case of ‘strategic ethnicity’? The Natal Indian Congress in the 1970s. African Historical Review, 46(1), pp.22-47.

- Van der Ross, R.E., 1975. “The founding of the African Peoples Organization in Cape Town in 1903 and the role of Dr. Abdurahman”.

- van Niekerk, R., 2014. SOCIAL DEMOCRACY AND THE ANC: BACK TO THE FUTURE?. A Lula Moment for South Africa: Lessons from Brazil, pp.47-61.

- Williams, D., 1970. “African nationalism in South Africa: origins and problems”. The Journal of African History, 11(3), pp.371-383.

Return to topic: Nationalism - South Africa, the Middle East, and Africa

Return to SAHO Home

Return to History Classroom

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Afrikaner nationalism is a political ideology of ethnic nationalism created by Afrikaners in Southern Africa. It differs from African nationalism in its opposition to British imperialism, its defense of Afrikaner culture and language, and its support for apartheid.

The rise of Afrikaner nationalism was incumbent on Afrikaners attitudes towards, reactions to and engrained social identity of class. A mutual understanding of the importance of class structure was a foundational way that Afrikaner mobilised their separate factions, joining together to battle against British imperialism and prospect of black ...

This article examines the origins and development of Afrikaner nationalism in South Africa, focusing on the role of agrarian crisis, social change, British imperialism and class realignment. It argues that Afrikaner nationalism was shaped by the struggle for land, identity and power, and by the contradictions of capitalism and apartheid.