An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A Study on the Impact of Organizing Environmental Awareness and Education on the Performance of Environmental Governance in China

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence: [email protected]

Received 2022 Sep 9; Accepted 2022 Sep 30; Collection date 2022 Oct.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

The advancement of technology and economic development has raised the standard of living and at the same time brought a greater burden to the environment. Environmental governance has become a common concern around the world, and although China’s environmental governance has achieved some success, it is still a long way from the ultimate goal. This paper empirically analyzes the impact of environmental publicity and education on environmental governance performance, using public participation as a mediator. The results show that: the direct effect of environmental publicity and education on environmental governance performance is not significant; environmental publicity and education have a significant positive effect on public participation; public participation significantly contributes to environmental governance performance; public participation shows a good mediating effect between environmental publicity and education and environmental governance performance. The government should adopt diversified environmental protection publicity and education in future environmental governance, and vigorously promote public participation in environmental governance so that the goal of environmental governance can be fundamentally accomplished by all people.

Keywords: environmental governance, environmental education and publicity, public participation, environmental governance performance

1. Introduction

With the progress of economic and social development, China’s urbanization is accelerating, and the increase in urban population has aggravated the deterioration of environmental pollution problems. With the rapid economic development and shortening of product life cycles, the rate of product replacement has become faster and faster, and the global energy shortage has caused increasing concern for environmental protection in various countries [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. China’s current ecological and environmental situation is very serious due to overpopulation, the long-term unreasonable exploitation of resources such as land, forests, water, and minerals, and the lack of necessary protection and construction of the ecological environment. At present, the deterioration of China’s ecological environment is summarized roughly as follows.

(1) Serious water and soil erosion. Soil erosion in China continues to show a “double decline” in area intensity and a “double reduction” in water and wind erosion. In 2021, the national soil erosion area will be 2,674,200 square kilometers, down 274,900 square kilometers from 2011, the percentage of strong and above grade will drop to 18.93%, and the soil and water conservation rate will reach 72.04% [ 4 , 5 ]. (2) The area of desertified land is expanding. The national desertification land area has reached 2.62 million square kilometers, accounting for 27.3% of the national land area, expanding at a rate of about 2460 square kilometers per year. (3) The area of degraded, sandy, and alkaline grassland is increasing year by year. The area of trivialized grasslands has reached 135 million hectares and is increasing at the rate of 2 million hectares per year [ 6 ]. (4) The area of acid rain area is further expanded, and the degree is worsening. Serious air pollution, mainly of the soot type, leads to a large area of acidic precipitation, and the area of acid rain area in China is about 466,000 square kilometers accounting for 4.8% of the national land area [ 7 , 8 ]. (5) The quality of the water environment is deteriorating, and water pollution accidents are frequent. According to incomplete statistics, in 2021, the country’s 458 daily discharge of direct sea pollution sources was more than 100 tons, the total volume of sewage discharge was about 7.28 billion tons, and they reported the largest integrated outfall emissions, followed by industrial sources of pollution, consequently, water shortage will be more serious [ 9 , 10 ]. (6) With the development of society, noise pollution has become an important source of pollution that affects people’s physical and mental health [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Noise pollution is recognized by the scientific community as an environmental pollutant related to sleep disorders and learning disabilities. Studies have shown that long-term exposure to highways, railroads, airports, and recreational noise can reduce work performance, make people irritable, and can seriously cause hypertension, heart attacks, and other diseases, which is also one of the sources associated with air pollution [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ].

National governments are paying more and more attention to environmental protection and ecological civilization construction work. To this end, they keep formulating and improving relevant laws and regulations, however, environmental protection is not only the task of the state and government, but also the responsibility and obligation of every resident, and long-term environmental protection and ecological civilization cannot be built without public participation. Under the constraints of environmental governance [ 26 ], environmental education can effectively improve people’s awareness of environmental protection [ 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Global environmental governance is the fundamental way to solve the human environmental crisis, and environmental awareness and education have been considered tools to help alleviate environmental problems [ 30 , 31 ]. Under the strong leadership of the Party Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping at the core, China’s higher education has moved with the times, built the world’s largest higher education system, cultivated a large number of high-quality specialists, and played an extremely important role in national revitalization, economic construction, social development, and scientific and technological progress. Historic achievements and changes in the pattern of higher education have been made. The world’s largest higher education system has been built, with the total number of students enrolled exceeding 44.3 million, and the gross enrollment rate of higher education has increased from 30% in 2012 to 57.8% in 2021, an increase of 27.8 percentage points, achieving a historic leap. Thus, higher education has entered a stage of universalization recognized worldwide. With 240 million people receiving higher education and an average of 13.8 years of education for the new workforce, the quality and structure of the workforce have undergone significant changes and the quality of the entire nation has been steadily improved. The awakening of public environmental awareness means that citizens gradually have a correct understanding of the relationship between human beings and nature in line with the essence of ecological civilization, and this awakening of environmental awareness needs to be inspired by education, and the process of gradually awakening environmental awareness is the process of gradually cultivating citizens into ecological citizens. Environmental education is the key to cultivating eco-citizens, and it has become an important value of environmental education in the context of ecological civilization construction to enhance citizens’ awareness of ecological civilization through environmental education. The government’s existing legislative practice of environmental education reflects the importance it attaches to the cultivation of ecological citizens through its environmental education training and other systems, i.e., the introduction of special legislation on environmental education. The awakening of public environmental consciousness requires the introduction of special legislation on environmental education to clarify the systems of ecological citizenship cultivation at the central level and effectively guarantee the effective development of ecological citizenship cultivation at the society-wide level, so as to promote the continuous awakening of citizens’ environmental consciousness and make all citizens in society become the main body in line with environmental protection and ecological civilization construction.

Liu P. pointed out in his study that perfect environmental protection propaganda and education work helps to enhance public participation in the construction of ecological civilization and protects the environment while safeguarding public interests; only by achieving universal environmental protection can we truly achieve long-term ecological civilization construction and the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation [ 32 ]. Fan Y.W. proposed corresponding strategies and measures by analyzing the complexity and forms of urban environmental governance in China, in which he proposed that the background of China’s rapid social and economic development hides a severe form of environmental governance, and the government should actively seek the support of enterprises, environmental organizations, and popular social forces while committing to sound policies and regulations and strict compliance, through more non-governmental forces’. In addition, public participation is an effective way to improve the efficiency of environmental protection, and through various forms of environmental protection publicity and education, the public’s environmental awareness and quality can be improved comprehensively, and the citizens’ legitimate right to supervision and information can be guaranteed [ 33 ]. Ecological environmental governance requires the collaborative participation of the government and the public, and that the two work together to provide services for environmental governance to achieve the optimization of the governance process and results. Public participation in environmental governance generates competent evaluations of external information perceptions based on their consciousness, among which the perceived evaluations of environmental risks, government performance, and self-efficacy all feature. The disclosure of bad environmental information can enhance the public’s perception of environmental risks, the threat of environmental pollution to their lives and the damage to their interests, consequently, stimulating the public’s defense mentality. Thus, introducing environmental education (especially, environmental health) could be used as one solution [ 34 ], promoting public participation in environmental governance, and good government environmental treatment performance can enhance the public’s satisfaction and recognition of government work, and increased satisfaction can enhance the public’s participation in environmental governance. The public’s participation in environmental governance has an obvious subjective motivation, and a good perception of self-efficacy can enhance the public’s enthusiasm to participate in environmental governance and help improve the performance of environmental governance [ 35 , 36 , 37 ].

In summary, environmental protection publicity and education can improve public perceptions of environmental protection, enhance public awareness of environmental protection, and promote public participation in environmental governance, and the government and the public can work together to serve environmental governance to maximize environmental governance performance [ 38 , 39 , 40 ]. Given the above literature findings, this paper takes public participation in environmental governance as an entry point to analyze in depth the impact of organizing environmental protection publicity and education on environmental governance performance and makes suggestions from the perspective of promoting public participation in environmental governance.

2. Research Hypotheses

2.1. impact of environmental awareness and education on environmental governance performance.

The Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) introduced policies and measures to modernize the governance system and governance capacity. As an important part of the modernized governance system, environmental governance, together with politics, economy, culture, society, and ecology, forms the national governance system. To fundamentally solve the task of urban environmental governance, it is necessary to create a situation of multi-governance, through environmental information disclosure and environmental education, to protect the legitimate rights and interests of citizens while enhancing the environmental awareness of social organizations and citizens. It is also helpful to improve the effectiveness of government environmental governance. It has been pointed out that the transparency and openness of environmental information have a significant impact on the performance of environmental governance and given the complexity, professionalism, and a certain degree of closure of environmental information, the right to information of citizens, enterprises, and social organizations is not fully guaranteed, which has a negative impact on the effectiveness of governmental environmental monitoring and governance. With the advancement of technology and the development of innovative environmental governance models, management mechanisms with high transparency and openness have become a new environmental governance model, which combines environmental information disclosure with environmental education to restrain corporate behavior, promote the participation and supervision of citizens and social organizations in environmental governance, and collaboratively improve government environmental governance performance [ 41 , 42 , 43 ]. Environmental information disclosure and publicity and education are complementary measures to environmental governance, and their actual effects are directly related to the strength of disclosure and publicity. Environmental information disclosure enhances the pressure faced by emission enterprises from public opinion and regulatory authorities, prompting them to increase the disclosure of environmental information, improve and upgrade their environmental protection technologies, and take up the environmental protection tasks they should accomplish. Environmental information disclosure combined with environmental publicity and education enhances the success of these efforts. The combination of environmental information disclosure and environmental education enhances public scrutiny of the effectiveness of environmental management by government departments and creates a multi-party accountability situation for local governments from higher levels of government, the public, and media opinion, prompting local governments to effectively implement environmental management [ 44 , 45 , 46 ]. In general, through environmental protection publicity and education, the supervision and pressure on emission enterprises and government departments through various aspects such as social organizations, citizens, and media public opinion have promoted the strength of environmental governance by government departments. Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Environmental protection publicity and education positively affect environmental governance performance .

2.2. The Impact of Environmental Publicity and Education on Public Participation

With the continuous improvement of living standards and education, although the environmental awareness of our residents has been greatly enhanced, there are still some shortcomings. The pilot implementation of many years of waste separation action at present the overall effect is poor, and the behavior of randomly throwing away garbage is still very common, the government vigorously promotes environmentally friendly consumer behavior also has little effect, “white pollution The problem of “white pollution” still exists. Industrial pollution caused by China’s rapid urbanization and industrialization is a serious threat to the ecological environment and human health, which stimulates public appeals for better environmental quality and public participation in regional environmental governance [ 47 ]. This shows that public awareness of environmental protection needs to be improved. Environmental protection publicity and education activities should reach out to the public and target outstanding environmental protection problems with the right remedy for publicity and education. On the one hand, popular publicity and education on environmental protection knowledge can be conducted in communities, schools, enterprises, cities, and villages to deepen public awareness of environmental protection and call for universal participation in environmental protection; on the other hand, thematic publicity and education activities can be held in regional water quality warning stations, air monitoring stations and motor vehicle, on the other hand, education activities can be held in regional water quality warning stations, air monitoring stations and motor vehicle exhaust testing centers, etc., with relevant professionals explaining environmental protection knowledge and issues that are closely related to the public [ 48 ]. Rural household waste management is an important part of building beautiful villages and achieving the goal of ecological livability, and the willingness of rural residents to participate in household waste management is influenced by a variety of factors such as economic conditions, environmental awareness, and regulations. The current level of participation in waste management initiatives is low overall. Some scholars used village cadres as an entry point to study and analyze the impact of environmental education on rural residents’ willingness to participate in domestic waste management, and the results showed that environmental education based on the moderating role of village cadres had a significant impact on rural residents’ willingness to participate in domestic waste management. Therefore, the government should carry out diversified methods of publicity and education to enhance residents’ environmental awareness and willingness to participate in environmental management, taking into account the actual needs [ 49 ]. Some studies have pointed out that environmental protection publicity and education is the guidance and interaction between society and public participation in environmental governance, and environmental protection is working closely related to everyone’s interests, and any social organizations and individuals have the obligation and responsibility to protect the environment, and through environmental protection publicity and education, the public is encouraged to participate in the supervision and management of environmental governance, and everyone, regardless of occupation or position, reflects their attitude and choice of environmental protection, and the whole population will be governed to completely solve environmental problems [ 50 , 51 , 52 ]. In summary, through various forms of environmental protection publicity and education, we can deepen the public’s understanding and awareness of environmental protection, make the public realize the connection between environmental protection and their own interests, promote public participation in environmental governance from both subjective awareness and objective needs, and enhance the willingness to participate [ 53 ]. Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Environmental protection publicity and education enhance the public’s willingness to participate .

2.3. Mediation Effect of Public Participation

Public participation in environmental governance not only refers to subjective environmental protection behaviors but more importantly, it is a variety of ways to monitor and put pressure on the government’s environmental governance work such as letters and visits, social organization intervention, litigation, and creating public opinion; environmental protection letters and visits, environmental protection litigation and social organization intervention can provide clues for the government’s environmental governance while creating public opinion creates greater pressure on the government’s environmental protection behaviors and enhances the public opinion has become a key factor in environmental governance in recent years [ 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 ]. In recent years, the public has become an important force in environmental governance, and the ways and means of public participation in environmental governance have been diversified, such as environmental petitions, environmental public opinion, CPPCC proposals, NPC motions, etc. Among them, environmental petitions reflect a more significant promotion effect on environmental governance performance than environmental public opinion, while the promotion effect of CPPCC proposals and NPC motions is not obvious, and the reason for this is that one of the main subjects of environmental governance, to avoid economic and social losses caused by environmental mass events caused by mishandling, so public demands are more important to local governments, and public environmental petitions can bring more pressure than CPPCC proposals and NPC motions, so the impact on environmental governance performance is greater [ 58 , 59 , 60 ]. Based on the interprovincial panel data from 2011–2015, some scholars constructed a model to empirically analyze the effects of three public participation channels, namely, complaint petitions, proposals, and self-media opinion, on regional environmental governance performance, and the results showed that public participation has a positive contribution to regional environmental governance performance, with the positive contribution effect of self-media opinion being the most significant. Based on the above literature, it can be seen that the ways of public participation in environmental governance are diversified and the effects of different ways on environmental governance performance vary, but promoting public participation in environmental governance through environmental education can indirectly contribute to the improvement of government environmental governance performance. Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Public participation can play a mediating effect between environmental publicity and education and environmental governance performance .

3. Research Design

3.1. data sources.

This paper used questionnaires to complete the data collection and acquisition. We randomly distributed questionnaires in townships, urban communities, enterprises, government environmental protection departments, and other related departments, the research subjects were township and urban community residents, enterprise middle-level and above managers, government environmental protection department staff and responsible person, government-related department staff and responsible person, etc., over 6 months, a total of 1200 questionnaires were distributed. After eliminating invalid questionnaires, a total of 1017 valid questionnaires were collected, with a valid recovery rate of 84.8%.

The content of the questionnaire was mainly for environmental protection publicity and education, public participation, and government environmental governance information survey. Each aspect contained a number of questions, using a five-level rating system to evaluate the valuation of each question, corresponding to completely not meet, not meet, not sure, meet, fully meet, respectively, assigned to the value of 1–5, environmental protection publicity and education, public participation and government environmental governance rating for the corresponding questions. The scores for environmental education, public participation, and government environmental governance were the sum of the corresponding questions [ 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 ]. The detailed questionnaire scale is shown in Table 1 .

Survey questionnaire scale design.

In order to ensure the credibility and validity of the questionnaire data, the reliability and validity of the scale need to be checked before the formal analysis, using Cronbach’s α reliability coefficient method and CITI value to test the data reliability, with α > 0.7 and CITI > 0.5 as the internal consistency of the questionnaire qualified, that is, the questionnaire has good stability and reliability, reliability test details The results are shown in Table 2 , the CITI values are greater than 0.5, and the reliability of all four variables is greater than 0.7, indicating that the questionnaire passed the reliability test.

Results of the reliability test of the questionnaire.

SPSS23.0 statistical software (IBM, New York, NY, USA) was used to conduct KMO and Bartlett sphere tests to verify the validity of the scale items, and the results showed that the KMO value was 0.966 and the Bartlett sphere test’s approximate chi-square value was 6139.573 ( p < 0.001), indicating that the scale items had good structural validity of cut elements in line with the conditions of factor analysis. The results of convergent validity and discriminant validity analysis of the sample data are shown in Table 3 and Table 4 . The data in the tables show that the factor loadings of the items are greater than 0.5, the CR values of the four variables are greater than 0.7, and the AVE values are greater than 0.5. The convergent validity and discriminant validity of the questionnaire data were good.

Results of convergent validity test.

Results of the discriminant validity test.

Note: ** indicates p < 0.01; diagonal values in the table are the square root of the AVE of the corresponding variable.

3.2. Model Design

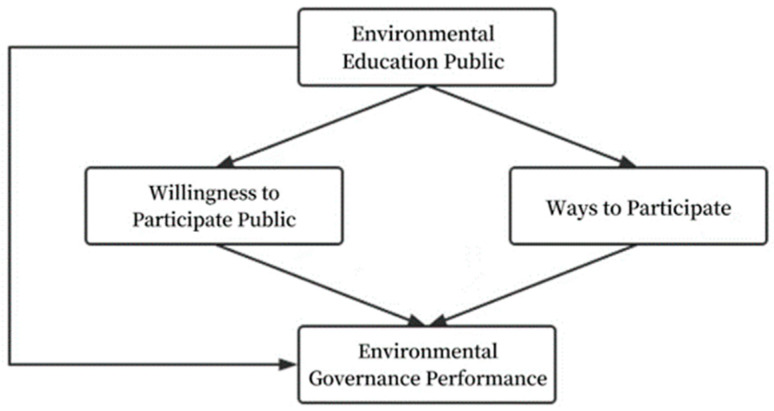

According to the analysis of the aforementioned literature, environmental protection publicity and education has a certain degree of positive impact on environmental governance performance, but it mainly has an indirect effect on environmental governance by influencing the will and ways of public participation in environmental governance, which has a direct impact on environmental governance. Based on the analysis of literature results, the theoretical model designed in this paper is shown in Figure 1 .

Theoretical structural model.

3.3. Model Test

The Mplus software was used to test the goodness-of-fit indicators of the structural model, and the test results are shown in Table 5 , from which it can be seen that all seven goodness-of-fit indicators meet the critical value requirements, indicating that the constructed model has good goodness-of-fit.

Structural model goodness-of-fit index measures.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. path analysis.

Based on the constructed theoretical structure model, and based on the sample data, Mplus software was applied to calculate the paths and impact relationships between environmental education, public participation, and environmental governance performance. The detailed results shown in Table 6 are not fully valid, the reason for this analysis is that the government, as one of the main participants in environmental publicity and education, organizes environmental publicity and education for the fundamental purpose of encouraging enterprises and the public to participate in environmental governance, and the direct effect of this on environmental governance performance is not significant. Both environmental publicity and education show a significant positive effect on public participation and public participation on environmental governance performance, indicating that environmental publicity and education can effectively promote public participation in environmental governance, and public participation in environmental governance significantly improves environmental governance performance.

Path analysis.

4.2. Mediating Effect Analysis

The results are shown in Table 7 , which shows that the confidence intervals of both the specific mediating effect and the total mediating effect are greater than 0, indicating that the mediating effects of public participation intention, public participation channel and This indicates that the mediating effects of public participation, public participation channels and public participation in environmental education and environmental governance performance are all valid, which verifies the hypothesis of this paper.

Intermediary effect test.

5. Conclusions and Discussions

This paper investigated the impact of environmental education on environmental governance performance, using public participation as the entry point for studying the mediating effects of environmental governance. The empirical results show that environmental publicity and education have a positive effect on environmental governance performance to some extent but are not significant. Environmental publicity and education have a significant positive effect on both public participation willingness and allocated resources; both public participation willingness and public participation significantly contribute to the improvement of environmental governance performance. Public participation shows a good mediating effect between environmental publicity and education and environmental governance performance [ 42 , 43 ].

Aldo Leopold, a famous American ecologist and founder of the land ethic, once said the essence of resource protection did not lie in a few government engineering programs, but fundamentally, in a change in the consciousness of all people. To protect the ecological environment, we should not only rely on the macro-control of government departments, and increase investment in environmental protection to take the path of sustainable development, but more importantly, we should improve the quality of awareness in the whole population, increase environmental publicity, and enhance environmental awareness. Environmental propaganda should adhere to the purpose of improving the environmental awareness of all sectors of society and the general public, decision-makers, factories and mining enterprises, young people, and society as a whole. All departments should make full use of the media and widely popularized scientific knowledge of environmental protection. Using close-to-life, reality-based publicity activities can enhance the nation’s environmental awareness and understanding of the legal system, leading to improvements in the public consciousness and increased participation in environmental action. Only in this way can we lay a good foundation for the smooth implementation of various policies and measures. Higher environmental awareness is a sign of progress in social civilization, and the higher the environmental awareness, the lower the resistance encountered to the implementation of environmental policies. Usually, it is necessary to continuously strengthen environmental publicity and education, and it is also possible to raise public environmental awareness by expanding the environmental rights and interests enjoyed by society, including the right to environmental supervision, the right to environmental information, the right to environmental claims, and the right to environmental discussion. In addition, the strengthening of environmental awareness must be accompanied by the construction of a supporting legal system, and the establishment of a virtuous ecological cycle by giving equal importance to ecological exploitation and protection and restoration as guidelines. Based on the theoretical results of the literature and combined with the results of the empirical analysis, this paper puts forward the following recommendations.

First, extensive participation in publicity and education. It is difficult for government-led publicity and education to cover all areas, so it is necessary to use the influence of corporate organizations and celebrities to expand the scope of environmental publicity and education. The cause of environmental protection concerns the vital interests of everyone; any social organization or individual has an obligation to take responsibility for protecting the environment and preventing pollution, so the ambitious goal of ecological livability and sustainable development cannot be achieved without joint efforts of all people and society as a whole.

Second, encourage public participation in environmental governance. The government should also take the lead in encouraging the public to participate in environmental management, and at the same time mobilize non-government forces to encourage public participation in environmental management. The government’s environmental management efforts will create a favorable social atmosphere. In addition, we should give full play to the role of private environmental organizations, guide and encourage them to participate in environmental governance, promote public supervision and media attention, and create a strong social force for environmental governance to comprehensively promote the goal of green development, which is also of great significance to China’s strategic goal of sustainable development.

Third, improve the relevant laws and regulations. The implementation of environmental protection policies cannot be implemented without the guarantee of laws and regulations, and perfect laws and regulations also have a direct impact on the operability of the relevant policies. We need to strengthen the establishment and implementation of laws and regulations related to environmental protection and rely on a sound legal system to comprehensively promote environmental governance. Scientific management systems, standardized operation processes, and strong supervision mechanisms are the important objective conditions for public participation in environmental governance. The environmental emergency management mechanism, media opinion monitoring mechanism, and environmental information disclosure mechanism need to be further supplemented and improved. A sound legal system can also provide the public with clear environmental rights, raise public awareness of environmental protection, and make the public participate more actively in environmental protection work. In short, a sound legal system is an important guarantee for public participation in environmental governance, and an important way to improve environmental governance performance.

Forth, improve the efficiency of government feedback. The government plays a role in guiding and interacting with the public in the process of environmental governance. Mass environmental incidents are typically generative of common demands for environmental governance from the public. If such demands do not receive timely and effective feedback from the government, it is likely to lead to a decrease in the public’s trust in the government and even trigger a crisis of government credibility. A positive interaction cycle between the public and the government is an important guarantee for the smooth development of the government’s environmental protection business, so the government should actively give feedback when the public clearly expresses their demands and give clear responses and answers to ensure smooth and harmonious communication between the two. In addition, the government environmental protection department should regularly sort out the statistics of public demands, actively solicit suggestions and opinions from the public, and make timely improvements in response to the shortcomings of the work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.N. and X.W.; methodology, Y.N.; software, Y.N.; validation, Y.N. and X.W.; formal analysis, Y.N. and X.W.; investigation, Y.N.; resources, Y.N.; data curation, Y.N.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.N.; writing—review and editing, Y.N. and X.W.; visualization, Y.N. and C.L.; supervision, Y.N. and X.W. and C.L.; project administration, Y.N. and C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

Jilin Province Higher Education Teaching Reform Research Project (Grant No. JLJY202140579379), Higher Education Teaching Reform Research Project of Jilin University (Grant No. 2021XZD028), Qingdao Social Science Planning Research Project (Grant No. 2022-389).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- 1. Jiang X.Y., Tian Z.Q., Liu W.J., Tian G.D., Gao Y., Xing F., Suo Y.Q., Song B.X. An energy-efficient method of laser remanufacturing process. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022;52:102201. doi: 10.1016/j.seta.2022.102201. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Mao J., Sun Q., Ma C., Tang M. Site selection of straw collection and storage facilities considering carbon emission reduction. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-15581-z. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Mao J., Liu R.P., Zhang X.Z. Research on smart surveillance system of internet of things of straw recycling process based on optimizing genetic algorithm. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2019;37:4717–4723. doi: 10.3233/JIFS-179306. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Jing X.K., Li L., Chen S.H., Shi Y.L., Xu M.X., Zhang Q.W. Straw returning on sloping farmland reduces the soil and water loss via surface flow but increases the nitrogen loss via interflow. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022;339:108154. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2022.108154. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Grahmann K., Rubio V., Perez-Bidegain M., Quincke J.A. Soil use legacy as driving factor for soil erosion under conservation agriculture. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022;10:822967. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.822967. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. He K.Y., Lu H.Y., Sun G.P., Wang Y.L., Zheng Y.F., Zheng H.B., Lei S., Li Y.N., Zhang J.P. Dynamic interaction between deforestation and rice cultivation during the holocene in the lower Yangtze River, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2022;10:849501. doi: 10.3389/feart.2022.849501. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Ali S.R. Impacts of acid rain on environment. ACADEMICIA Int. Multidiscip. Res. J. 2021;11:776–781. doi: 10.5958/2249-7137.2021.02669.0. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Tripathi A.D. Environmental impact of acid rain: A review. Asian J. Multidimens. Res. 2021;10:592–597. doi: 10.5958/2278-4853.2021.01041.7. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Han Y., Li N., Mu H., Guo R., Yao R., Shao Z. Convergence study of water pollution emission intensity in China: Evidence from spatial effects. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022;29:50790–50803. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-19030-3. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Huang Y., Mi F., Wang J., Yang X., Yu T. Water pollution incidents and their influencing factors in China during the past 20 years. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022;194:182. doi: 10.1007/s10661-022-09838-4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Muzet A. Environmental noise, sleep and health. Sleep Med. Rev. 2007;11:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2006.09.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Zacarias F.F., Molina R.H., Ancela J.L.C., Lopez S.L., Ojembarrena A.A. Noise exposure in preterm infants treated with respiratory support using neonatal helmets. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2013;99:590–597. doi: 10.3813/AAA.918638. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Erickson L.C., Newman R.S. Influences of background noise on infants and children. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2017;26:451–457. doi: 10.1177/0963721417709087. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Babisch W., Beule B., Schust M., Kersten N., Ising H. Traffic noise and risk of myocardial infarction. Epidemiology. 2005;16:33–40. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000147104.84424.24. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Petri D., Licitra G., Vigotti M.A., Fredianelli L. Effects of exposure to road, railway, airport and recreational noise on blood pressure and hypertension. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:9145. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179145. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Vukic L., Mihanovic V., Fredianelli L., Plazibat V. Seafarers’ Perception and Attitudes towards noise emission on board ships. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:6671. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126671. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Rossi L., Prato A., Lesina L., Schiavi A. Effects of low-frequency noise on human cognitive performances in laboratory. Build. Acoust. 2018;25:17–33. doi: 10.1177/1351010X18756800. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Miedema H., Oudshoorn C. Annoyance from transportation noise: Relationships with exposure metrics DNL and DENL and their confidence intervals. Environ. Health Perspect. 2001;109:409–416. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109409. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Cueto J.L., Petrovici A.M., Hernández R., Fernández F. Analysis of the impact of bus signal priority on urban noise. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2017;103:561–573. doi: 10.3813/AAA.919085. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Fredianelli L., Carpita S., Bernardini M., Pizzo L.G.D., Brocchi F., Bianco F., Licitra G. Traffic flow detection using camera images and machine learning methods in ITS for noise map and action plan optimization. Sensors. 2022;22:1929. doi: 10.3390/s22051929. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Ruiz-Padillo A., Ruiz D.P., Torija A.J., Ramos-Ridao Á. Selection of suitable alternatives to reduce the environmental impact of road traffic noise using a fuzzy multi-criteria decision model. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2016;61:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2016.06.003. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Bunn F., Zannin P.H.T. Assessment of railway noise in an urban setting. Appl. Acoust. 2016;104:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.apacoust.2015.10.025. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Iglesias-Merchan C., Diaz-Balteiro L., Solino M. Transportation planning and quiet natural areas preservation: Aircraft overflights noise assessment in a National Park. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015;41:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2015.09.006. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Fredianelli L., Gaggero T., Bolognese M., Borelli D., Fidecaro F., Schenone C., Licitra G. Source characterization guidelines for noise mapping of port areas. Heliyon. 2022;8:e09021. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09021. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Nastasi M., Fredianelli L., Bernardini M., Teti L., Fidecaro F., Licitra G. Parameters affecting noise emitted by ships moving in port areas. Sustainability. 2020;12:8742. doi: 10.3390/su12208742. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Guo M., Cai S. Impact of green innovation efficiency on carbon peak: Carbon neutralization under environmental governance constraints. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:10245. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191610245. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Xu K., Tian G. Codification and prospect of China’s codification of environmental law from the perspective of global environmental governance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:9978. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19169978. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Yang B., Wu N., Tong Z., Sun Y. Narrative-based environmental education improves environmental awareness and environmental attitudes in children aged 6–8. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:6483. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19116483. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Wang J.L., He Y.Y., He X., Jiao Y.M., Wang X.F., Li Y. Comparative analysis of environmental awareness of primary and middle school students in Kunming. Yunnan Environ. Sci. 2001;20:20–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Kiziroglu I. Education and research on environmental awareness in Turkey. CLEAN Soil Air Water. 2007;35:534–536. doi: 10.1002/clen.200790043. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Soares J., Miguel I., Venâncio C., Lopes I., Oliveira M. On the path to minimize plastic pollution: The perceived importance of education and knowledge dissemination strategies. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021;171:112890. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112890. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Liu P. A few thoughts on environmental protection publicity and education under the new situation. Resour. Conserv. Environ. Prot. 2020;3:1. [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Fan Y.W. Urban environmental management measures in the construction of ecological civilization. Resour. Conserv. Environ. Prot. 2019;7:1. [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Sendari S., Ratnaningrum R.D., Ningrum M.L., Rahmawati Y., Rahmawati H., Matsumoto T., Rachman I. Developing emodule of environmental health for gaining environmental hygiene awareness. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019;245:012023. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/245/1/012023. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Di W. Research on the status of environmental education in China’s capital universities. selecting Peking University as a sample. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2014;13:1079–1088. doi: 10.30638/eemj.2014.113. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Fan Y.S. Information disclosure, environmental regulation and environmental governance performance—Empirical evidence from Chinese cities. Ecol. Econ. 2020;36:7. [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Duan X., Dai S., Yang R., Duan Z., Tang Y. Environmental collaborative governance degree of government, corporation, and public. Sustainability. 2020;12:1138. doi: 10.3390/su12031138. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Guo J., Bai J. The role of public participation in environmental governance: Empirical evidence from China. Sustainability. 2019;11:4696. doi: 10.3390/su11174696. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Yang Y.L., Lu A.J., Zhang Z.Q. Can government environmental information disclosure promote environmental governance?—An empirical study based on 120 cities. J. Beijing Univ. Technol. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2020;22:8. [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Qian M., Cheng Z., Wang Z., Qi D. What affects rural ecological environment governance efficiency? Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19:5925. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19105925. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Kumar R. The United Nations and Global Environmental Governance. Strateg. Anal. 2020;44:479–489. doi: 10.1080/09700161.2020.1824462. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Bodin O., Baird J., Schultz L., Plummer R., Armitage D. The impacts of trust, cost and risk on collaboration in environmental governance. People Nat. 2020;2:734–749. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10097. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Wang J.J., Chen Y. Research on the path of propaganda and education of the rule of law in colleges and universities in New Epoch; Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Modern Management, Education Technology and Social Science (MMETSS 2018); Zhuhai, China. 28–30 September 2018; pp. 64–68. [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Ge T., Hao X.L., Li J.Y. Effects of public participation on environmental governance in China: A spatial Durbin econometric analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021;321:129042. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129042. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Cichon M., Warachowska W., Lowicki D. Attitudes of young people towards lakes as a premise for their public participation in environmental management. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021;9:683808. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2021.683808. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Wang X., Zhang J.B., He K. Does environmental education increase rural residents’ willingness to participate in domestic waste management?—A moderating effect analysis based on the status of village cadres. Arid. Zone Resour. Environ. 2021;35:7. doi: 10.13448/j.cnki.jalre.2021.208. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Rameli E. Information broadcasting concerning publicity and public participation in development plan. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Education. 2021;12:715–722. doi: 10.17762/turcomat.v12i2.928. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Long T., Chaiyachati K.H., Khan A., Siddharthan T., Meyer E., Brienza R. Expanding health policy and advocacy education for graduate trainees. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2014;6:547–550. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00363.1. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Zou P. Publicity and education are fundamental to China’s family planning programme. China Popul. Newsl. 1987;4:1–4. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Connell R.W. Propaganda and education: Political training in the schools. Aust. J. Educ. 1970;14:155–167. doi: 10.1177/000494417001400204. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Chen W.D., Yang R.Y. Government regulation, public participation and environmental governance satisfaction—The empirical analysis based on CGSS2015 data. Soft Sci. 2018;32:5. doi: 10.13956/j.ss.1001-8409.2018.11.11. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Edsand H.E., Broich T. The impact of environmental education on environmental and renewable energy technology awareness: Empirical evidence from Colombia. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2020;18:611–634. doi: 10.1007/s10763-019-09988-x. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Lee Z.H. The impact of public participation on local government environmental governance—An empirical analysis of inter-provincial data from 2003–2013. Chin. Adm. 2017;8:102–108. doi: 10.3782/j.issn.1006-0863.2017.08.16. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Chen H., Nyaranga M.S., Hongo D.O. Enhancing public participation in governance for sustainable development: Evidence from Bungoma County, Kenya. SAGE Open. 2022;12:21582440221088855. doi: 10.1177/21582440221088855. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Lihua W.U., Tianshu M.A., Bian Y., Li S., Yi Z. Improvement of regional environmental quality: Government environmental governance and public participation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;717:137265. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137265. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Lu A.J. The impact of public participation on the effectiveness of environmental governance: An empirical study based on ladder theory. China Environ. Manag. 2021;013:119–127. [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Mukhtarov F., Dieperink C., Driessen P. The influence of information and communication technologies on public participation in urban water governance: A review of place-based research. Environ. Sci. Policy. 2018;89:430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2018.08.015. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Cent J., Grodzinska-Jurczak M., Pietrzyk-Kaszynska A. Emerging multilevel environmental governance—A case of public participation in Poland. J. Nat. Conserv. 2014;22:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2013.09.005. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Kousar S., Afzal M., Ahmed F., Bojnec T. Environmental awareness and air quality: The mediating role of environmental protective behaviors. Sustainability. 2022;14:3138. doi: 10.3390/su14063138. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Zuzek D.K. Environmental awareness of society and resulting environmental threats; Proceedings of the 19th International Scientific Conference “Economic Science for Rural Development 2018”; Jelgava, Latvia. 9–11 May 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- 61. Bennett N., Satterfield T. Environmental governance: A practical framework to guide design, evaluation, and analysis. Conserv. Lett. 2018;11:e12600. doi: 10.1111/conl.12600. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 62. He J. Study of college students’ environmental awareness cultivation under the view of ecological civilization; Proceedings of the 2016 International Forum on Energy, Environment and Sustainable Development; Shenzhen, China. 16–17 April 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- 63. Wan Q.J., Deng H.Q. The effects of group identity on pro-environmental behavioral norms in China: Evidence from an experiment. Front. Psychol. 2022;13:865258. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.865258. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 64. Coenen J., Bager S., Meyfroidt P., Newig J., Challies E. Environmental governance of China’s belt and road initiative. Environ. Policy Gov. 2020;31:3–17. doi: 10.1002/eet.1901. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (567.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

environmental awareness Recently Published Documents

Total documents.

- Latest Documents

- Most Cited Documents

- Contributed Authors

- Related Sources

- Related Keywords

Green HRM, environmental awareness and green behaviors: The moderating role of servant leadership

Effectiveness and benefits of the eco-management and audit scheme: evidence from polish organisations.

Climate change and environmental pollution are considered to be among the main challenges faced by the modern world. The growth of environmental awareness and the adoption of a pro-environmental approach are considered to be the key megatrends with the greatest impact on the global economy in the upcoming years. According to Eurobarometer, EU citizens are particularly aware of the importance of protecting the environment. Although the negative environmental impact of European industry has improved over the past decades, EU citizens believe that there is further scope in terms of helping companies transition towards adopting more sustainable models. One of the factors contributing to the reduction in negative environmental impact is the participation of enterprises in voluntary programs such as the Environmental Management System (EMS), according to ISO 14001, or the Eco-management and Audit Scheme (EMAS). The whole population of Polish companies registered under the EMAS was included in the study and although the sample size was small, it was a full study, and for that reason allows for the generalisation and conclusion regarding the whole population of EMAS-registered companies in Poland. The results of the study conducted on EMAS-registered organisations in Poland in 2015 suggest that the average effectiveness of the EMAS observed between 2007 and 2014 was 66.4%. The aim of this study was to review the changes in EMAS effectiveness and benefits obtained by participating organisations after five years. The results indicate that the average effectiveness during the period of 2015–2020 increased to 79.1%; nevertheless, registered organisations recognise fewer benefits for participation in the scheme. The study has shown that as EMAS matures in organisations, it becomes more effective. It influences a lot of factors, such as environmental awareness and management commitment, the use of SRDs (including BEMPs), environmental performance indicators for specific sectors, the criteria for the excellence of assessing the level of environmental performance, and the skilful use of indicators in organisations.

Analysis of Urban Residents’ Willingness to Pay for Forest Ecological Services Based on the Multilayer Linear Model

This study takes 8 cities in Shaanxi province as the research object and uses the multilayer linear model specifically for nested structure data to introduce the urban macroexplanatory variables on the basis of individual level of residents and influence the willingness of urban residents to pay for forest ecological services. The factors are analyzed in multiple layers to find out the prediction effect on ecological payment, and on this basis, corresponding countermeasures and suggestions are put forward. The results show that regional differences have a significant impact on residents’ willingness to pay for forest ecological services; individual characteristics and regional characteristics can independently have a significant impact on residents’ willingness to pay; after introducing macrolevel variables, individual-level environmental awareness and per capita income, five variables, such as education level, place of residence, and age, have significant predictive effects on residents’ willingness to pay; among them, the interaction between consumer price index and environmental awareness is the largest, followed by the interaction between consumer price index and age. Per capita social security is the interaction between expenditure and environmental awareness. Finally, that is the interaction between the per capita social security expenditure and age and the interaction between the average salary of employees and the monthly per capita income.

A Game-Based Content and Language-Integrated Learning Practice for Environmental Awareness (ENVglish)

Increasing human activities in the environment have created severe effects; therefore, handling such effects by raising environmental awareness through several ways has become significant to sustain the environment, which can enhance 21st century skills including critical thinking and information literacy. Digital games can be used for this because they create an environment for learning with higher engagement, motivation, and excitement besides fostering cognitive attainment and retention. Accordingly, a mobile game-based content and language-integrated learning practice (an educational digital game called ENVglish) was developed to raise EFL students' environmental awareness in this qualitative study. During the design and development phases of the game, students' and teachers' perceptions regarding it were collected with semi-structured interviews. The data were content analyzed. The findings indicated that both students and teachers had positive perceptions about the game and that students could improve their English and have environmental awareness with the game.

The Effect of Beauty Consumers’ Environmental Awareness on Clean Beauty Brand Attachment and Purchase Intention

Can social media be a tool for increasing tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior.

For the sustainable development of a tourism destination, environmentally responsible behavior (ERB) is a vital issue. This study developed an implicated model based on the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) framework showing the usages of social media by tourists regarded as a stimulus; environmental awareness, and place attachment generated from using social media regarded as an organism; and tourists' ERB thereby bringing behavioral intension regarded as responses. The integrated tourists' ERB model was experimentally tested using survey data from 467 Bangladeshi tourists by SEM-based methodology. The study found that social media has a beneficial effect on environmental awareness and place attachment, negatively impacting ERB. Furthermore, environmental awareness and place attachment has a favorable impact on ERB. This article discusses theoretical discoveries as well as practical consequences.

Impact of Social Desirability and Environmental Awareness on Ecological Behavior among Students

In present scenario, Indian government has regulated many policies and pro environment action with an aim of being aware about environment under which we continue to live. Although, it is not only government responsibility towards developing pro environment attitude rather it should be emerges from us for our nature. However, people become more sensitive for their livelihood needs than environmental concerns which are remarkable notion. So, the present study attempted to study the pro environment attitude and ecological behavior dynamics with an influence of social desirability.

The Moderator Role of Environmental Interpretations in the Relationship between Planned Behavior Level and Environmental Awareness Perception of Hotel Employees

Environmental problems, environmental awareness, and efforts to protect the environment are among the issues that concern the whole world and that need to be acted upon. Environmental concerns, which have come to the fore, especially in recent years, are closely related to the tourism sector. The main purpose of this research is to determine the moderator role of environmental interpretations in the relationship between planned behavior levels and environmental awareness perceptions of hotel employees. The sample of the research consists of 697 employees, who worked in five-star hotels in the Alanya region between the months of August and September 2020. As the data collection method in the research, the questionnaire technique has been preferred. As a result of the data obtained from the research, the Amos program was used to test the structural model. Respectively, these analyzes are reliability analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, discriminant analysis, and regression analysis. As a consequence of the regression analysis conducted within the context of the study, it has been determined that the level of attitude, which is considered to be one of the planned behavior factors of the employees in the hotel enterprises, has a positive and significant effect on their environmental awareness. In addition, it has been determined that environmental interpretations have a moderating role in the relationship between the attitude levels and environmental awareness of the employees, participated in the research.

Território ribeirinho e a reprimarização do açaí: O caso da várzea de Abaetetuba/PA

O presente artigo discute os aspectos da territorialidade ribeirinha de Abaetetuba, no estado do Pará, com foco na produção do açaí (Euterpe oleracea) no município de Abaetetuba, considerando a importância do açaí como base alimentar dos ribeirinhos do município, assim como o consumo em várias escalas. A pesquisa objetiva analisar a territorialidade ribeirinha na inserção do açaí na lógica de reprimarização da economia no município. Foram realizadas quinze entrevistas com pessoas que atuam diariamente nos elos da cadeia produtiva do açaí, realizadas nos meses de julho e agosto de 2021, com intuito de identificar a realidade atual produtiva do produto, frente o aumento da demanda e consequentemente a pressão exercida na várzea para garantir a oferta. A pesquisa mostra que a conscientização ambiental não alcança de maneira homogênea os agentes que atuam nos elos das cadeias, mas sim que há um distanciamento significativo por parte de quem não mora nas ilhas. Já os ribeirinhos em si possuem esta consciência, porém há uma apropriação das relações de ancestralidade que existem entorno do açaí, pelo neoextrativismo e que mantém a tendência monucultural do açaí, considerando que essa estratégia tende minimizar as possibilidades de conflito pelo uso do território ribeirinho, em função de ter sido implantado por meio de uma atividade produtiva de cunho ancestral, com isso se mantém as relações desiguais que a reprimarização necessita para se consolidar na várzea de Abaetetuba. Palavras-chave: Território; ribeirinho; açaí; reprimarização da economia; Abaetetuba. Abstract This paper discusses the aspects of ribeirinho territoriality of Abaetetuba in the Brazilian state of Pará, focusing on the production of açaí (Euterpe oleracea) in Abaetetuba municipality, considering the importance of açaí as the food base of the ribeirinho dwellers, as well as its consumption at various scale levels. The research aims to analyze the municipality’s ribeirinho territoriality in terms of the insertion of açaí in the logic of reprimarization of the local economy. Fifteen interviews were conducted with people who work daily in the links of the açaí production chain in the months of July and August 2021, in order to identify the current productive reality of the fruit, in face of the trend of incrementing both the demand and the pressure exerted on the floodplain to guarantee supply. The research shows that the environmental awareness does not reach homogeneously the agents that act in the links of the chains, but that there is a significant distancing on the part of those who do not live on the local space. The ribeirinho dwellers themselves show this awareness, but there is an appropriation of açaí’s ancestral relations by neoextractivism, and this maintains the monocultural trend of the fruit, considering that this strategy tends to minimize the possibilities of conflict for the use of ribeirinho territory, because it was implemented through a productive activity of ancestral nature, thus maintaining the unequal relations that reprimarization needs to consolidate itself in the floodplain of Abaetetuba. Keywords: Territory; ribeirinhos; açaí; reprimarization of the economy; Abaetetuba. El territorio ribereño y la reprimarización del açaí: El caso de la llanura de inundación de Abaetetuba (PA) Resumen Este trabajo discute los aspectos de la territorialidad ribereña de Abaetetuba, en el estado brasileño de Pará, centrándose en la producción delaçaí (Euterpe oleracea) en el municipio de Abaetetuba, considerando la importancia del açaí como base alimenticia de los ribereños delaciudad, así como el consumo de ello en diversas escalas. La investigaciónpretendeanalizar la territorialidad ribereña en la inserción del açaí en la lógica de reprimarización de la economía en el municipio. Se realizaron 15 entrevistas a personas que trabajan diariamente en posiciones de la cadena productiva del açaí, realizadas en los meses de julio y agosto de 2021, con el fin de identificar la realidad productiva actual del fruto, frente al aumento de la demanda y, en consecuencia, de la presión ejercida sobre la llanura de inundación para garantizar el suministro. La investigación muestra que la concienciación medioambiental no llega de forma homogénea a los agentes que actúan en los anillos de la cadena, sino que hay un distanciamiento significativo por parte de los que no viven en el espacio. Los propios ribereños tienen esta conciencia, pero hay una apropiación de las relaciones ancestrales que existen en torno al açaí, por parte del neoextractivismo,lo que mantiene la tendencia monocultural del açaí, considerando que esta estrategia tiende a minimizar las posibilidades de conflicto por el uso del territorio ribereño, debido a que se han desplegado a través de una actividad productiva de carácter ancestral, con esto se mantienen las relaciones desiguales que la reprimarización necesita para consolidarse en la llanura de inundación de Abaetetuba. Palabras clave: Territorio; Ribereño; Açaí; Reprimarización de la economía; Abaetetuba.

The Name of Grim: Tracing the Character of Grim the Collier in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century English Theatre

Grim the Collier is a curious comic character who receives little critical attention. Grim appears in three key plays, sixteenth- and seventeenth-century pamphlets, herbals, and ballad culture. This article examines, and rejects, Grim as a potentially useful figure for environmental awareness. I dispel legends about the basis of this character, and examine how the labile significance of the name ‘Grim’ implicates it in networks of superficial similarity between devils, colliers, and racialized black skin. These networks link to the proverb that underlies most early modern depictions of Grim: ‘like will to like quoth the devil to the collier’.

Export Citation Format

Share document.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Environmental awareness Questionnaire The Environmental awareness questionnaire was subjected to pre-testing, which is, in fact, a 'dream rehearsal' of the fi nal study. The Environmental awareness questionnaire was administered to a sample of hundred and twelve students studying in schools. The validity of the EAS was found 0.84.

PDF | The ill-effect of environmental destruction is evident and its future potentialities are immense. Environmental awareness through education,... | Find, read and cite all the research you ...

Explore the latest full-text research PDFs, articles, conference papers, preprints and more on ENVIRONMENTAL AWARENESS. Find methods information, sources, references or conduct a literature review ...

Environmental education in the Philippines has been incorporated to different course curricula including life and physical sciences, social studies, geography, civics, and moral education.

environmental awareness is high as revealed by one study (Anilan, 2014). The level of environmental awareness and practices on recycling of solid wastes in one university campus in Malaysia was likewise gauged (Omran, Bah & Baharuddin, 2017). In the Philippines, the Department of Education (DepEd), the Commission on Higher

All research papers submitted to the journal will be double ... In spite of the government's effort in promoting environmental awareness through Republic Act 9512, which mandates the promotion of ...

This paper aims to identify the status on the level of environmental awareness in the concept of sustainable development among secondary school students. ... attitudes and noble values of sustainability and environmental awareness). The research instrument is the questionnaire using Likert scale with five (5) alternatives rating. The Cronbach ...

This paper investigated the impact of environmental education on environmental governance performance, using public participation as the entry point for studying the mediating effects of environmental governance. ... Kiziroglu I. Education and research on environmental awareness in Turkey. CLEAN Soil Air Water. 2007; 35:534-536. doi: 10.1002 ...

For the sustainable development of a tourism destination, environmentally responsible behavior (ERB) is a vital issue. This study developed an implicated model based on the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) framework showing the usages of social media by tourists regarded as a stimulus; environmental awareness, and place attachment generated from using social media regarded as an organism ...

Journal of Nature Studies 17(1): 56-67 ISSN: 1655-3179 ENVIRONMENTAL AWARENESS AND PRO-ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIORS OF HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS IN LOS BAÑOS, LAGUNA Pauline Nicole dela Peña1*,Aprhodite M. Macale2 and Nico N. Largo3 1Natural Sciences Research Institute, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines 2 College of Arts and Science, University of the Philippines Los Banos,