Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 21 June 2024

Bridging the digital divide: the impact of technological innovation on income inequality and human interactions

- Anran Xiao 1 ,

- Zeshui Xu 1 ,

- Marinko Skare ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6426-3692 2 ,

- Yong Qin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4966-7899 1 &

- Xinxin Wang 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 809 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

7077 Accesses

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

This study seeks to understand the nuanced relationship between technological innovation and income inequality with an emphasis on the broader implications of this interplay on human–technology interactions in diverse socioeconomic settings. Using cross-country panel data from 59 nations (31 developed and 28 developing) from 1995 to 2020, the study employed the common correlated effect mean group (CCEMG) estimator. The robustness of our findings was validated using the augmented mean group (AMG) estimator and the panel causality test. The results indicate that technological innovation, while heralded for its potential to bridge communication and operational gaps, inadvertently exacerbates income disparities, with a pronounced effect in developed economies. Moreover, interactions between technological innovation and variables such as economic growth, globalisation and export trade introduce additional complexities, including both buffering and acceleration effects on the primary relationship. These findings shed light on the double-edged nature of technological advancements, underscoring the need for informed policy-making that harnesses the benefits of innovation while mitigating its unintended socioeconomic consequences. The study sets the stage for domain-specific explorations such as in education, public health and business. It also invites interdisciplinary discourse on the ethical and behavioural dimensions of technology adoption, especially user experiences and societal outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

ICTs and economic performance nexus: meta-analysis evidence from country-specific data

Time-varying interrelations between digitalization and human capital in Vietnam

Breaking through ingrained beliefs: revisiting the impact of the digital economy on carbon emissions

Introduction.

Income inequality (INE) refers to the difference in income distribution between various individuals or groups and is an ongoing issue that has been in the spotlight for the past several decades (Kuznets, 1955 ). As shown in Fig. A1(a) of the appendix , in 2021, the top 10% of the global population accounts for 52% of global income, whereas the bottom 50% only has 8% of it (WIL, 2022 ). According to the Human Development Report in 2021/2022 (UNDP, 2022 ), rising economic hardship and INE are driving trends in polarisation, which results in social turmoil, political contradiction and armed conflict that impede economic development and disrupt lives all over the world. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic sounded the alarm on the fragility of economic systems and has imbued countries with a sense of fear and danger. This has shattered the dream of rapid development and driven a chasm between the rich and the poor. Based on the data released by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), there were 473 million unemployed people worldwide in 2022, with those in low-paying occupations and informal employment struggling and suffering the most (ILO, 2023 ). Simultaneously, the pandemic has further exposed the weaknesses and injustice in global health and education systems. Reducing vulnerability, sustaining growth and eradicating poverty are becoming increasingly important in addressing persistent INE (Law et al. 2020 ). According to the Global Education Monitoring Report, despite the wide-scale adoption of digital technologies, there still exist significant disparities in access among various economic groups (UNESCO, 2023 ). Rapid advancements in digital technologies has indeed ushered in groundbreaking innovations and opportunities worldwide. However, the gap in access to digital technologies among different income groups leads to information asymmetry and knowledge gaps, forming the complex dynamic process of the so-called digital divide (Van Dijk and Hacker, 2003 ). As shown in the appendix, Fig. A2 , there is a deep divide in internet connectivity between the rich and the poor. This interplay between humans and technology introduces additional complexities to diverse socioeconomic settings. In summary, it is critical to delve further into the determinants of INE and their interactions with technology, which contribute to formulating targeted policies to bridge the gap and advance societies towards inclusion.

Technological innovation is the application of new knowledge to improve production tools, processes, products, or services in a specific field through research and development, experimentation and promotion. Technological innovation is the fundamental driving force behind economic growth and has been identified in endogenous growth theory (Howitt and Aghion, 1998 ; Romer, 1986 ) and evolutionary economics (Dosi, 1982 ). The inverted U-curve hypothesis proposed by Kuznets ( 1955 ), which elucidates the relationship between economic growth and INE, has been widely developed in economic and environmental fields. There are some inextricable nexuses between INE and technological innovation that provoke scholarly debate. Despite the benefits of technological change to economic growth, there is a dark side of exacerbating INE. While numerous studies have demonstrated that technological innovation contributes to economic growth by boosting productivity and creating more occupations, it also widens the income gap (Antonelli and Scellato, 2019 ; Tang et al. 2022 ). Biased technical innovation and technology spillovers are the two primary ways in which technological innovation affects INE. Technological innovation increases the demand for skilled and knowledge-intensive jobs, leading to a substantial replacement of low-skilled labour by high-skilled labour, eventually resulting in lower-skilled labour falling into unemployment and being ensnared in lower-paying jobs (Perera-Tallo, 2017 ). Consistent with this explanation, skill-biased innovation changes the market structure, widening the wage gap between skilled and unskilled workers (Acemoglu, 1999 ; Florida et al. 2017 ). These findings undoubtedly pour cold water on the enthusiasm of enterprises, policymakers and inventors for innovation.

However, some empirical evidence suggests the opposite conclusion. A basket of policies oriented towards technological innovation tends to counteract the inequality-exacerbating effect (Yeo et al. 2021 ). Moreover, information and communications technology (ICT) contributes to the inequality-diminishing effect in the long run (Nguyen et al. 2020 ). More contextualised studies carried out by Adams and Akobeng ( 2021 ) reached the same conclusion that technological innovation reduces INE. Additionally, some studies explore how inequality expands or diminishes through the interaction of technological innovation and other variables, such as globalisation, financial development, democracy, regulatory quality and institutional quality (Adams and Akobeng, 2021 ; Asamoah et al. 2021 ; Law et al. 2020 ). Moreover, research on the interaction effect and reverse causality suggests that the potential feedback mechanisms and pathways between technological innovation and inequality are worth further investigating (Abakumova and Primierova, 2018 ; Koh et al. 2020 ).

Against this backdrop, some critical issues also warrant further investigation. First, the literature mainly focuses on the direct impact of technological innovation on INE, neglecting to explore potential feedback mechanisms and possible pathways between the two. Second, the direct impacts of economic growth, globalisation and export trade on inequality are popular and classic topics that spawn numerous plausible conjectures and spark a range of discussions on socioeconomic issues. However, there is little empirical evidence to directly support the moderating effect of these factors on the links between technological innovation and INE. Finally, the impact of technological innovation on inequality varies across different subperiods and groups due to significant historical variations in factors such as global trade policies, economic development and financial markets. However, the heterogeneity analysis by the level of economic development and chronology is not yet conclusive, leaving a gap for further investigation. The need for an in-depth analysis of the issues above motivates the study’s goal to investigate the nexus between technological innovation and income equality and whether the links between them are subject to economic growth, globalisation and export trade. As a result, more thorough research with a rigorous design is needed.

This study collected cross-country panel data for 31 developed and 28 developing countries from 1995 to 2020 for the empirical analysis. The common correlated effect mean group (CCEMG) estimator is employed to uncover the direct and interaction effects among the variables after confirming the series data’s slope coefficient heterogeneity and cross-sectional dependence (CD). For comparison, the augmented mean group (AMG) estimator is applied to the robustness test, while the Dumitrescu and Hurlin panel causality test is employed to detect the potential feedback loop.

In comparison to prior research, our study makes three valuable and novel contributions to the literature. First, the study examines the direct impact of technological innovation on INE and explores the potential feedback mechanisms between the two. Unfair income distribution, which is present in both developed and developing countries, is a negative effect of technological innovation. In contrast, developed countries are more deeply ensnared in the technological innovation-induced inequality trap. Second, there is substantial variation between developed and developing countries in how technological innovation interacts with economic growth, globalisation and export trade, leading to diverse moderating effects on INE. The role of moderating variables give clues to potential routes to reverse INE and guide policy formulation. Third, a heterogeneity analysis is conducted to explore the nexus between technological innovation and INE under various chronologies. Finally, a basket of comprehensive policies is proposed from the perspectives of improving human capital and overcoming biased technological innovation. The strategy of inclusive innovation diffusion aims to break down the digital divide, bridge the digital gap and guarantee the equity and accessibility of digital technology. As the active driving force of economic growth and productivity, technological innovation still holds promise for the renewal of policies and adoption of change towards achieving sustainable and inclusive growth. These targeted policies closely intertwine physical resources, human capital and technological innovation, complementing each other to jointly achieve inclusive and permanent growth of the economy, society and technology.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section “Literature review” presents the literature review and hypothetical development. Section “Empirical model and methodology” introduces the data collection, empirical model and econometric methods. Section “Empirical results” reports the empirical results and describes the corresponding analysis. Section “Discussions” implements some the discussions and commentary from direct effect, moderating effects and heterogeneity analysis. Finally, Section “Conclusion” draws the conclusion and policy implications.

Literature review

Links between ine and technological innovation.

Although numerous studies have emphasised that income distribution, which is heavily skewed towards a select few people, undermines the economic opportunities of the general public, the literature has some limitations in exploring the link between technological innovation and INE (Gama et al. 2019 ). On the one hand, some studies focus on the economic growth effects of technological innovation while ignoring its potential impact on income distribution. On the other hand, the role of technological innovation in income redistribution is also an extensively studied and meaningful topic, but the existing research often lacks sufficient empirical support or theoretical depth (Biggi and Giuliani, 2021 ; X. Zhang et al. 2022 ).

Some research supports the positive role of technological innovation in reducing INE. The Schumpeterian hypothesis is tested by Antonelli and Gehringer ( 2017 ), who asserted that technological innovation abates wealth and rent disparity, resulting in less INE. An empirical study in advanced countries spanning from 1995 to 2011 supports that radical labour-intensive technological innovation plays a crucial role in effectively reducing wage and INE by increasing the share of income for labour and distributing it equally among workers (Antonelli and Tubiana, 2023 ). Innovative technologies have the potential to initially bring quick profits to entrepreneurs but they exacerbate the economic gap. The survival of incumbents is seriously threatened by technological updates and iteration, as well as the creative destruction brought on by entrants, thus resulting in the obsolescence of the original technology, lower enterprise profits and lessening inequality (Jones and Kim, 2018 ). A 2022–2014 study on 87 countries found the spread of mobile and internet technologies contributes to the inequality-diminishing effect in the long run (Nguyen et al. 2020 ). Similarly, another study on 46 African countries from 1984 to 2018 concluded that ICT development decreases inequality and that governance measures strengthen and solidify the negative relationship between the two (Adams and Akobeng, 2021 ). These studies suggest that technological innovation can be an effective tool for reducing economic inequality. Moreover, the policy environment also plays an important role in moderating the relationship between technological innovation and INE. Although human capital development augments wealth inequality, comprehensive policies in the face of technological innovation can reverse it (Ojha et al. 2013 ). Therefore, government policies can also reinforce the negative relationship between technological innovation and the reduction of inequality (Adams and Akobeng, 2021 ). Policy packages that integrate physical, human and technical progress substantially impact income fairness (Yeo et al. 2021 ). Table 1 lists some representative literature about the links between technological innovation and INE. Based on the above discussion, we formulate the first hypothesis:

H1a . Technological innovation reduces income inequality.

However, the emergence and proliferation of innovative technologies can also create a host of challenges and risks that can exacerbate economic inequality. Technological innovation’s exclusivity, heterogeneity and inaccessibility have exposed this dark side and consequently catalysed unfair income distribution. Biased technological change is one of the determinants mentioned. Assets and labour are two sources of income, and biased technological change expands the share of income to assets while simultaneously squeezing the proportion of income to labour. The distribution of assets is more uneven than that of labour due to the heterogeneity of savings rates between the poor and the rich, engendering greater income asymmetry (Perera-Tallo, 2017 ). Consistent with this, structure changes in the labour market due to skill-biased technological advancement intensify worker unemployment and job polarisation. It accounts for a wider wage gap between skilled and unskilled workers (Acemoglu, 1999 ; Florida et al. 2017 ). Compared to population growth, land-biased technology more adequately accounts for inequality (Madsen and Strulik, 2020 ). The beneficiaries of technological innovation are concentrated among highly skilled professionals with great learning capacities and resources, reflecting the conflicts and disparities between those who gain from technological innovation and those who lack access to it. In other words, technological innovation widens the income gap between high-tech and low-tech workers (Butler and Dueker, 1999 ). The impact on INE is heterogeneous across sectors and countries (Adebayo, 2022 ; González Gordón and Resosudarmo, 2019 ). The financial sector wage premium contributes a significant portion to the global top-income growth in many countries, and the financial sector’s higher rent is responsible for the rapidly growing global inequality (Biyase et al. 2023 ; Card et al. 2018 ). The pattern of rent sharing between workers and companies is also a potential source of high wages in the financial sector (Hm and Metzger, 2023 ). Therefore, the exclusive benefits of technical progress to specific institutions partially exacerbate the contradiction of INE (Tang et al. 2022 ). Antonelli and Scellato ( 2019 ) argue that there is a strong link between wage inequality and targeted technological change, which directly affects INE and influences capital-intensive technological change, thereby exacerbating rent inequality. After analysing panel data for 23 developed countries, Law et al. ( 2020 ) drew the same conclusion that technological innovation fails to promote a more equitable income distribution. Overall, while technological innovation may offer great potential for economic growth and efficiency gains, its impact on income distribution is not always positive. Rapid technological change may lead to the demise of certain industries or types of work, thereby exacerbating INE. In addition, technological innovation may also escalate the conflict between capital and labour, as new technologies tend to generate profits first for the owners of capital rather than for workers. Based on the arguments above, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1b . Technological innovation exacerbates income inequality.

Roles of economic growth, globalisation and export trade

The relationship between economic growth and INE has always been a topic of concern. The traditional “Kuznets inverted-U curve hypothesis” asserts that economic growth results from industrialisation and urbanisation. As the economy grows, trends in INE undergo a change and show an inverted U-shape (Kuznets, 1955 ). In the early phases, the proportion of the non-agricultural sector in the economy as a whole gradually expanded, increasing income disparities. In subsequent stages of higher economic growth, as the income gap within sectors narrows, the share of inequality determinants decreases, income redistribution measures are introduced, and the income distribution tends to become more equitable. However, the inverted-U curve hypothesis has been widely debated. The theory of the economic growth-inequality nexus has been considerably expanded by applying richer empirical data and persuasive econometric approaches (Deininger and Squire, 1996 ; Kanbur, 1993 ; Wang et al. 2023 ). Martin and Chen ( 1997 ) argued that growth does not necessarily cause polarisation or inequality. When economies are in structural transition, zero growth exacerbates poverty. Specifically, the choice of sample group affects the association between economic growth and polarisation. Economic growth reduces poverty and polarisation in the entire sample. Nevertheless, when partial sample groups are excluded, the data reveal no correlation or discernible trend, disproving the inverted U-curve hypothesis. Similarly, some research indicates that there is no association between inequality and economic development (Hartono and Irawan, 2008 ). When considering the income levels of various groups, the relationships between GDP and INE depend on the initial income of the country (Brueckner and Lederman, 2018 ). A study of Indonesia from 2000 to 2010 considered sectoral heterogeneity. A higher proportion of GDP in the agricultural sector drastically reduces INE, but the reverse trend is found for manufacturing and services (González Gordón and Resosudarmo, 2019 ).

Moreover, in contrast to the inequality-exacerbating effect (Hailemariam et al. 2021 ), some empirical research shows a negative long-run equilibrium and even a nonlinear relationship between economic growth and inequality (Gil-Alana et al. 2019 ; Rougoor and Marrewijk, 2015 ). In the samples grouped by economic growth-related indicators, the impact of economic growth on inequality tends to be heterogeneous across countries (Acheampong et al. 2023 ; Ghosh and Mitra, 2021 ; Tica et al. 2022 ). Furthermore, technological innovation plays an important role in the relationship between economic growth and inequality. On the one hand, technological innovation can promote economic growth by improving production efficiency and industrial upgrading. On the other hand, technological innovation can have a significant impact on income distribution. In general, there is a need for more research on the interaction of GDP and technological innovation and how it affects inequality. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis.

H2a . Economic growth significantly moderates the relationship between technological innovation and inequality.

Trade openness, international investment, the expansion of ICT and cross-border labour movements are just a few of the complex economic and social drivers of globalisation, which have sparked a growing discussion over how they affect INE (Badur et al. 2023 ; Villanthenkodath et al. 2023 ). Globalisation speeds up technological advancement, promoting the incentive and capacity to create and profit from cutting-edge knowledge, resulting in a wage premium for highly skilled employees in organisations, which widens the income gap (Aghion and Howitt, 1998 ). On the one hand, globalisation causes the cross-sectoral redistribution of plentiful skilled labour, which generates idiosyncratic production shocks when complemented by unskilled labour. On the other hand, technological innovation is affected by the conflict between new open trade and the old market. Both increase personal income risks, particularly in poorer sectors where the effects are more noticeable than in wealthier sectors (Helpman et al. 2010 ). In other words, globalisation intensifies income polarisation in each country, narrowing the gap in the middle (J. Anderson, 2008 ). More contextualised research by Krugman ( 2008 ) concluded that increased trade expands the wage gap between skilled and unskilled workers. Due to their propensity to focus on non-skilled, intensive niche markets, developing countries are more significantly impacted by globalisation than developed countries are. A study on EU-27 countries from 1995 to 2009 distinguished between the effects of trade globalisation and financial globalisation on inequality, holding the view that trade opening is more favourable for advancing equality (Asteriou et al. 2014 ).

Globalisation has also brought about unequal changes within and between countries. Some studies indicate that globalisation increases inequality within countries while reducing inequality across nations (Lang and Tavares, 2023 ). Consistent with this conclusion, Adams and Klobodu ( 2017 ) investigated 21 sub-Saharan African countries and concurred that in addition to remittances, external debt and aid flows, foreign direct investment exacerbate INE in both the long and short terms. However, the discussion about the relationship between globalisation and inequality still needs to be deepened. Academic research differs in the selected countries, endogeneity of trade, and methodologies, leading to disparate opinions on the impact of globalisation (Law et al. 2020 ). Moreover, globalisation has multiple dimensions, both de facto and de jure, and its effects on INE may vary. In summary, the impact of globalisation on INE is a complex and multidimensional issue. Future research is needed to further explore the various dimensions, mechanisms and dynamics of globalisation and how technological innovation regulates this relationship. To conclude, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2b . Globalisation significantly moderates the relationship between technological innovation and inequality.

Some evidence strongly indicates that trade openness benefits productivity, leads to income redistribution and affects poverty growth (Adao et al. 2022 ; Topalova, 2010 ). Unlike the heterogeneity of sectors, the endogeneity of trade and the emergence of disparities between economies, the effect of trade openness on inequality remains nebulous, requiring compelling data to establish (Huang et al. 2022 ). According to the standard Heckscher–Ohlin (HO) model, trade openness reduces trade barriers, raises the relative demand for unskilled labour, and narrows the wage gap in poor countries. However, international trade increases inequality because of the availability and endowment of skilled labour in developed countries. A rising body of evidence challenges the HO model, leading researchers to seek pertinent theoretical justifications for this emerging trend. Lee et al. ( 2022 ) and Gharleghi and Jahanshahi ( 2020 ) reported that trade liberalisation and inequality are significantly positively related. Firm size and industry heterogeneity have an impact on the income distribution resulting from opening trade (Adao et al. 2022 ), leading to income discrepancies between industries and subsequently exacerbating INE (Anderson, 2011 ). Trade can give rise to more significant wealth disparity and greater unemployment.

Similarly, according to Dinopoulos and Segerstrom ( 1999 ), trade liberalisation encourages technical advancement in skill-intensive industries, lowering the pay of unskilled employees and promoting skill upgrades. Contrary to this conclusion, according to a meta-analysis of 494 estimates, Huang et al. ( 2022 ) suggested that it is overblown to worry about trade-expanding inequality, which suggests that trade aids in reducing inequality rather than creating a chasm between the wealthy and the impoverished. In an analysis of Brazilian states, it is surprising to find that integrated trade is disaggregated into imports and exports, exerting different effects on inequality. A boost in exports reduces inequality and poverty, while increasing imports worsen national poverty (Castilho et al. 2012 ). The empirical evidence from Pakistan has shown that trade promotes income equality over the long term; thus, it is necessary to exert sustained efforts to improve labour and capital mobility (Khan et al. 2021 ). According to Lee et al. ( 2022 ), export diversification is also a determinant of inequality, but when political risk is considered an interaction term, the situation is reversed; that is, INE decreases. The interaction between trade openness and digitalisation curbed INE in 20 countries from 2002 to 2018 (Yin and Choi, 2023 ). Nevertheless, this effect is heterogeneous by income and development level (Wang et al. 2023 ). Based on the above discussion, the last hypothesis is developed as follows:

H2c . Export trade significantly moderates the relationship between technological innovation and inequality.

Empirical model and methodology

This section covers three parts, including data collection, the empirical model and the econometric technique. First, this paper selects 31 developed countries and 28 developing countries as research subjects and collects five kinds of data, including technological innovation capacity, INE, economic growth, globalisation and the export of services and goods. To accurately explore the relationships between variables, we establish four paradigms of econometrics. These paradigms not only focus on the direct relationship between technological innovation and INE but also delve into the interaction between technological innovation and three other factors. To ensure the reliability of the study, we apply the comprehensive strategy of econometric modelling, which is detailed in the appendix (Fig. A3 ). Then, the CCEMG estimation method is employed to explore the direct and interaction effects between the variables, while the AMG estimation method is used for the robustness test.

Data collection

The goal of the current study is to investigate the nexus between technological innovation (INNO) and income equality (INE), as well as how economic growth (GDP), globalisation (GLO) and exports of services and goods (ESG) either strengthen or diminish the links in both developed and developing countries. This empirical study gathers panel data for 31 developed and 28 developing countries from 1995 to 2020 and compiles a list of countries, which are specified in the Appendix file along with the summary statistics). The INE used for regression estimation is proxied by the top 10% income share from the WID (World Inequality Database), which is the percentage of total national income owned by the wealthiest group of people (Aghion et al. 2019 ; Brzezinski, 2022 ). Most academic studies use the number of patents as the most reliable indicator of technological innovation (INNO) (Adams and Akobeng, 2021 ; Nguyen et al. 2020 ). Thus, we use it as a proxy for national innovation capacity. Numerous studies utilise GDP per capita from the World Bank as a proxy for economic growth (GDP) since it reflects a country’s level of economic development. Globalisation is a complex and abstract concept driven by numerous economic and social factors that are challenging to measure (Mills, 2009 ). Therefore, we chose the KOF Index of Globalisation to represent a country’s level of globalisation (GLO), which measures the economic, social and political drivers involved in globalisation (Gygli et al. 2019 ; Qin et al. 2023 ; Shahbaz et al. 2015 ). Exports of goods and services (% of GDP) provided by the World Bank are taken as a criterion of export trade ( EGS ) to represent the economic value of all products and other market services exported to the rest of the world. We employ human capital ( HC ), represented by the World Bank’s indicator of the labour force, as a control variable for the model (Philippon and Reshef, 2012 ). According to the World Bank, the labour force refers to persons 15 years of age and older who provide labour for producing goods and services during a specific period. More detailed descriptions of the variables and data sources are presented in the Appendix (Tables A1 and A2) . These chosen variables are transformed by the natural logarithm to stabilise the variance‒covariance matrix and lessen the likelihood of heteroscedasticity (Usman and Radulescu, 2022 ).

The descriptive statistics for all the data for developing and developed countries are shown in the Appendix (Table A3) , from which we can infer that INE is lower in developed countries than in developing countries. Nevertheless, the opposite is true for technological innovation. This study initially performed a Pearson correlation coefficient test for each variable before the regression estimation (Fig. A4 ). INE is positively correlated with technological innovation but negatively correlated with export trade and globalisation. At the same time, further research is required to thoroughly and systematically investigate their intertwined relationship. Similar conclusions may be drawn from the scatter plot on INE and technological innovation (Fig. A5 ), demonstrating a positive association between the two variables in developed and developing nations.

Empirical model

The comprehensive literature review and hypothesis development serve as the foundation for the econometric model specification, which concentrates on two key topics: (i) Model I: The direct impact of technological innovation (INNO) on INE and (ii) Model II–Model VI: The interaction effect of economic growth (GDP), globalisation (GLO) and exports of services and goods (ESG) on INE. The distribution becomes homogeneous after taking the logarithms of variables, which also guarantees the stability and normality of the model (Usman and Radulescu, 2022 ). Therefore, the models mentioned above are all presented in logarithmic form. The heated debate over the nexus between technological innovation and INE is given above for Model I. Thus, it is reasonable to believe that there are long-term correlations between them, and the relevant empirical model can be articulated as follows:

where INE, INNO and Control are employed to symbolise INE, technological innovation, and control variables, respectively. i = 1, ⋯ , N and t = 1, ⋯ , T denote the economies (31 developed countries and 28 developing countries) and the time period (1995–2020), respectively; θ i indicates the individual effects; β 1 and ζ i denote the coefficients of the independent variable and the control variable, respectively; μ it represents the error term, and it is assumed that cross-sectional correlation holds.

The indirect effects of economic development, globalisation and export trade on INE are revealed in the literature review. However, the research tweaks around the edges rather than delving deeply. Extending the benchmark Model I in Eq. ( 1 ) is critical to further explore the interaction effects of economic growth, globalisation and export trade as moderators. Therefore, the specific interaction effect models, Model II, Model III and Model IV, are shown below:

where \(\mathrm{ln}\,{\rm{INNO}}_{it}\ast \,\mathrm{ln}\,{\rm{GDP}}_{it}\) , \(\mathrm{ln}\,{\rm{INNO}}_{it}\ast \,\mathrm{ln}\,{\rm{GLO}}_{it}\) and \(\mathrm{ln}\,{\rm{INNO}}_{it}\ast \,\mathrm{ln}\,{\rm{ESG}}_{it}\) represent the interaction terms between technological innovation and economic growth, globalisation and export trade, respectively; β 1 reflects the impact of technological innovation on INE when ln GDP is zero, according to Eq. ( 5 ), which shows the marginal change in INE relative to technological innovation. Similarly, Eq. ( 6 ) indicates that β 2 captures the effect of economic growth on INE when ln INNO is zero. As a result, it is not feasible to interpret β 1 and β 2 in isolation in the model with interaction terms (Brambor et al. 2006 ). β 3 is the coefficient of the interaction terms, and its significance requires special attention, which suggests the role of the moderators (ln GDP, ln GLO and ln ESG) in buffering or exacerbating the links between technological innovation and INE.

This research establishes a comprehensive and robust econometric modelling strategy to investigate the effect of technological innovation on INE and the interaction effect of economic growth, globalisation and export trade through numerous econometric methods.

Econometric methods

The CD test becomes essential for capturing the dependence among economies in panel data. There may be an increased likelihood of CD due to the various dimensions of globalisation, such as trade openness, financial development, and technological innovation across countries (Badur et al. 2023 ; Qin et al. 2023 ). CD among cross-sections is a problem that must be addressed, or the results of the estimate will be biased, inefficient, and erroneous (Huang et al. 2022 ). Therefore, before discussing the stationarity of the data, the CD test is the initial analysis for the variables and the long-run estimations of the panel. Three approaches are employed in this paper to test CD, namely, the methods of Friedman ( 1937 ), Frees ( 1995 ) and Pesaran ( 2004 ). They are expressed in Eq. ( 7 ), Eq. ( 8 ) and Eq. ( 9 ), respectively. The null hypothesis states that there is no cross-sectional correlation ( H 0 ).

Panel unit root tests

Unlike the first-generation unit root tests, which are not applicable in the presence of CD, the CIPS test proposed by Pesaran ( 2007 ) performs well in CD and permits unit roots in heterogeneous panels. ADF regression is adjusted by employing mean and first difference lagged cross-sections, and the detailed calculation process is given as:

where \({\bar{y}}_{t}\) is the mean value of the variable y it for time t . Similarly, the CIPS calculates the mean of the t -statistics for each cross-sectional unit, as shown in the following equation:

where CADF is the cross-sectional ADF, and the null hypothesis accepts that there is a unit root in the tested variable ( H 0 ).

Testing for slope heterogeneity

With deepening economic integration with globalisation, shocks have cascading repercussions. Hence, cross-country panel data frequently exhibit slope heterogeneity and CD. Traditional slope heterogeneity tests fail to consider CD. Pesaran and Yamagata ( 2008 ) proposed the SCH test, which better addresses CD and heterogeneous slopes (Wei and Huang, 2022 ). The detailed model is shown below:

where \(\tilde{\Delta }\) stands for the delta tilde and \({\tilde{\Delta }}_{adj}\) denotes the adjusted delta. For comparison, the serial correlation and heteroskedasticity robust version of the SCH test suggested by Blomquist and Westerlund ( 2013 ) are employed in the study.

CCEMG method

This paper employs the CCEMG estimator proposed by Pesaran ( 2006 ) to explore the effect of technological innovation on INE and the roles of economic growth, globalisation and export trade. In addition to addressing worldwide and regional unobservables and missing variables, CCEMG can remove economic cycles using annual data (Law et al. 2020 ). The CCEMG estimator has two noteworthy advantages. On the one hand, unlike the common correlated effect pooled (CCEP) estimator, CCEMG considers slope coefficient heterogeneity and cross-sectional correlation. The model introduces unobservable factors to eliminate cross-sectional correlations.

On the other hand, this method is applicable regardless of whether there is a cointegration relationship between variables. As a result, even in serial autocorrelation, unit roots, cross-sectional dependency, and heteroskedasticity, the CCEMG estimator produces unbiased, consistent and stable regression results (Kapetanios et al. 2011 ). The CCEMG model is described in detail below:

where \({\bar{C}}_{it}\) and \({\bar{D}}_{it}\) represent the mean values of the dependent and independent variables, respectively, and \({f}_{t}=({f}_{1t},{f}_{2t},{f}_{3t},\mathrm{..}.,{f}_{mt})^{\prime}\) denotes the latent common factors that are stationary or non-stationary and consider cross-sectional dependency. It affects every cross-section simultaneously, leading to correlations among cross-sections; \({\lambda }_{i}^{\prime} =({\lambda }_{i1},{\lambda }_{i2},\ldots ,{\lambda }_{im})^{\prime}\) indicates the loading component of the heterogeneous factor and represents the stochastic residual term. Finally, the CCEMG estimator determines the outcome by calculating the average slope of all cross-sections, and the specific equation is shown below:

where \({\hat{\beta }}_{i}\) represents the coefficient of each cross-section.

The AMG estimator of Eberhardt and Bond ( 2009 ) is employed for the robustness test. Unlike CCEMG, AMG addresses the unobserved common factor as a dynamic standard process and considers co-dynamic effects to account for the CD. Therefore, similar to the CCEMG estimator, the AMG estimator is robust to slope heterogeneity and CD. To estimate unobservable common dynamic effects, the AMG estimator employs a two-step process, which is shown as follows:

Step I of AMG:

Step II of AMG:

where Δ stands for the first-order difference, \({\hat{\mu }}_{t}^{\cdot }\) represents the year dummy coefficients, and e t is related to the time dimension coefficient. The final results are calculated by the average of the statistical coefficients for N countries.

Causality test

The aforementioned CCEMG estimator provides the coefficients of the long-term relationship between variables. Nevertheless, it cannot explore the causal relationship and direction between the independent and dependent variables. This is detrimental to formulating more efficient and applicable policies. Therefore, this study employs the causality test proposed by Dumitrescu and Hurlin ( 2012 ) to investigate the causal relationship between INE and other variables due to its excellent adaptability, accuracy and unbiasedness for addressing CD and slope heterogeneity issues even in imbalanced panels ( N ≠ T ) (Gu et al. 2021 ). The detailed calculation process is given as follows:

where Wald i,t denotes the Wald statistics and \({\rm{Wald}}_{N,T}^{HNC}\) represents the average value of all cross-sectional Wald statistics.

Empirical results

We conducted the CD test by applying the methods of Friedman ( 1937 ), Frees ( 1995 ) and Pesaran ( 2004 ), and the outcome of the CD test is presented in Table A4 . The null hypothesis can be rejected because all outcomes are significant, proving the CD across the series data. The growing tendency towards trade liberalisation, financial growth and technological change across economies may be the origin of the CD problem (Badur et al. 2023 ). The international trade of ICT products and services strengthens technological innovation spillover effects, significantly affecting the business performance of sectors with high technological dependence (Castellani and Fassio, 2019 ). All pre-modelling test results are available in the Appendix file .

Slope heterogeneity test results

In addition to the issue of CD, it is crucial to pay particular attention to the heterogeneity of the slope coefficients. If the slope coefficients are incorrectly assumed to be homogenous, then this may result in biased regression findings. The values of Δ and Δadj are both significant according to the SCH tests of Pesaran and Yamagata ( 2008 ) and Blomquist and Westerlund ( 2013 ), suggesting the rejection of the null hypothesis that slope coefficients are homogeneous ( H 0 ). In light of the above analysis, the issues of CD and slope heterogeneity exist in panel data. Thus, subsequent stationarity tests are limited to using second-generation unit root approaches.

Unit root results

The prior CD test strongly proved the existence of the CD problem in the panel series data; hence, two different methods of second-generation unit root tests, namely, CADF and CIPS (Pesaran, 2007 ), are used to assess the stationarity of variables both at levels I(0) and at the first difference I (1). The results of the CIPS and CADF tests indicate that the null hypothesis of the existence of a unit root ( H 0 ) cannot be rejected at levels I (0). However, all outcomes are significant and reject the null hypothesis when the variables are processed for first-order differences. As a result, we can move on to the following step because the series data are stationary.

Regression results

The benchmark model explores how technological innovation affects INE in both developed and developing countries, and the results are presented in Table 2 . A 1% increase in technological innovation leads to a 0.041% increase in INE in developed countries (Column 1). Similarly, a 1% increase in technological innovation increases INE by 0.017% in developing countries (Column 2). Technological innovation exacerbates INE in both developed and developing countries. Thus, we reject H1a. This is in line with Arocena and Sutz ( 2003 ), who asserted that due to differences in individual learning capacities, technological innovation fosters wealth disparity as the population grows. Frydman and Papanikolaou ( 2018 ) concluded that the prospective investor talent of executives in the context of technological innovation brings greater rewards, increasing the gap between executives and regular workers. Based on these results, developed countries are more deeply ensnared in the technological innovation-induced inequality trap than are developing countries. Additionally, this effect is more significant in developed countries. This is explained by Iwaisako ( 2009 ), who contended that the production shift to developing countries is to blame for the widening wage gap for skilled labour in developed countries. The production shift encourages R&D investment, thus increasing the share of unproductive activities and the demand for R&D labour, ultimately increasing INE in developed countries. Partially diverging from this conclusion, Maggie Fu et al. ( 2021 ) argued that INE is not significant in developed economies because low-skilled workers complement other productive factors, and the potential endowment of high-skilled workers is difficult to substitute for innovative products. Moreover, the increase in productivity resulting from innovative products eliminates part of the income gap.

To more thoroughly investigate the pathways and mechanisms by which technological innovation indirectly affects income equality, the meditators of economic growth, globalisation and export trade are introduced to interact with technological innovation. The interaction effect model examines the roles of economic growth, globalisation and export trade in the nexus of technological innovation and INE in both developed and developing countries, and the findings are shown in Tables 3 and 4 . Notably, the values of the three interaction terms are significant, indicating that economic growth, globalisation and export trade act as moderators with a significant strengthening or weakening effect on the links between technological innovation and INE.

Model II portrays the impact of the interaction between economic growth and technological innovation on INE. The empirical results show that a 1% increase in the interaction term between economic growth and technological innovation leads to a 0.21% increase in INE in developed countries (Column 1 in Table 3 ), demonstrating that economic growth exacerbates inequality. However, the opposite is true for developing countries, where a 1% increase in the interaction between technological innovation and economic growth reduces the income gap by 0.221% (Column 1 in Table 4 ). The interaction between economic growth and technological innovation is similar to a timely catalyst, facilitating the shift from inequality exacerbating to inequality diminishing. This view is supported by González Gordón and Resosudarmo ( 2019 ), who contended that the growth-inequality relationship has sectoral heterogeneity and that agricultural sector growth is more inclusive than that of other sectors. Conversely, evidence from China spanning 1980–2013 has shown that economic growth could accelerate inequality in the long run (Koh et al. 2020 ).

Model III illustrates how globalisation and technological innovation interact to affect income disparity. Based on the empirical results, the interaction terms of globalisation and technological innovation are negatively signed and significant at the 5 and 10% levels in both developing and developed countries, respectively. Specifically, a 1% increase in the interaction between globalisation and technological innovation leads to a 0.909% decrease in INE in developed countries (Column 2 in Table 3 ). Likewise, a 1% increase in the interaction between globalisation and technological innovation would reduce the income gap by 0.361% in developing countries (Column 2 in Table 4 ). Globalisation is a boon to reducing INE in developed and developing countries, albeit this inequality-diminishing effect is more obvious in developed countries. In summary, technological innovation and globalisation work together to lower INE. This finding is consistent with Shahbaz et al. ( 2015 ), who asserted that globalisation is negatively linked to INE. The labour premium decreases due to increased patents, complemented by globalisation, boosting employment prospects for skilled and unskilled labour. As a result, it improves income distribution and decreases INE (Cattani et al. 2022 ). This finding contradicts the findings of Abakumova and Primierova ( 2018 ), who confirmed the positive association between globalisation and INE.

Model IV represents the effect of the interaction between export trade and technological innovation on INE. This proves that a 1% increase in the interaction term between export trade and technological innovation leads to a 0.38% decrease in INE in developed countries (Column 3 in Table 3 ), which indicates that export trade and technological innovation interact to act as an opportune trigger, turning the tables to complement each other. In other words, the interaction between export trade and technological innovation contributes to the diminishing effect of inequality. More contextualised studies conducted by Huang et al. ( 2022 ) complemented the perspective that there is no reason to be unduly concerned about the effects of trade openness because trade reduces INE in middle-income and high-income countries, which is insignificant in low-income countries. In contrast, a 1% increase in the interaction between export trade and technological innovation would widen the income gap by 0.102% in developing countries (Column 3 in Table 4 ), meaning that export trade undoubtedly drives INE caused by technological innovation. This conclusion is also obtained by Mah ( 2013 ) in research on China from 1985 to 2007, which supported the role of trade liberalisation as a driver of INE. However, this result is partially inconsistent with that of Gharleghi and Jahanshahi ( 2020 ), who concluded that trade benefits deteriorate income distribution in developing or developed countries.

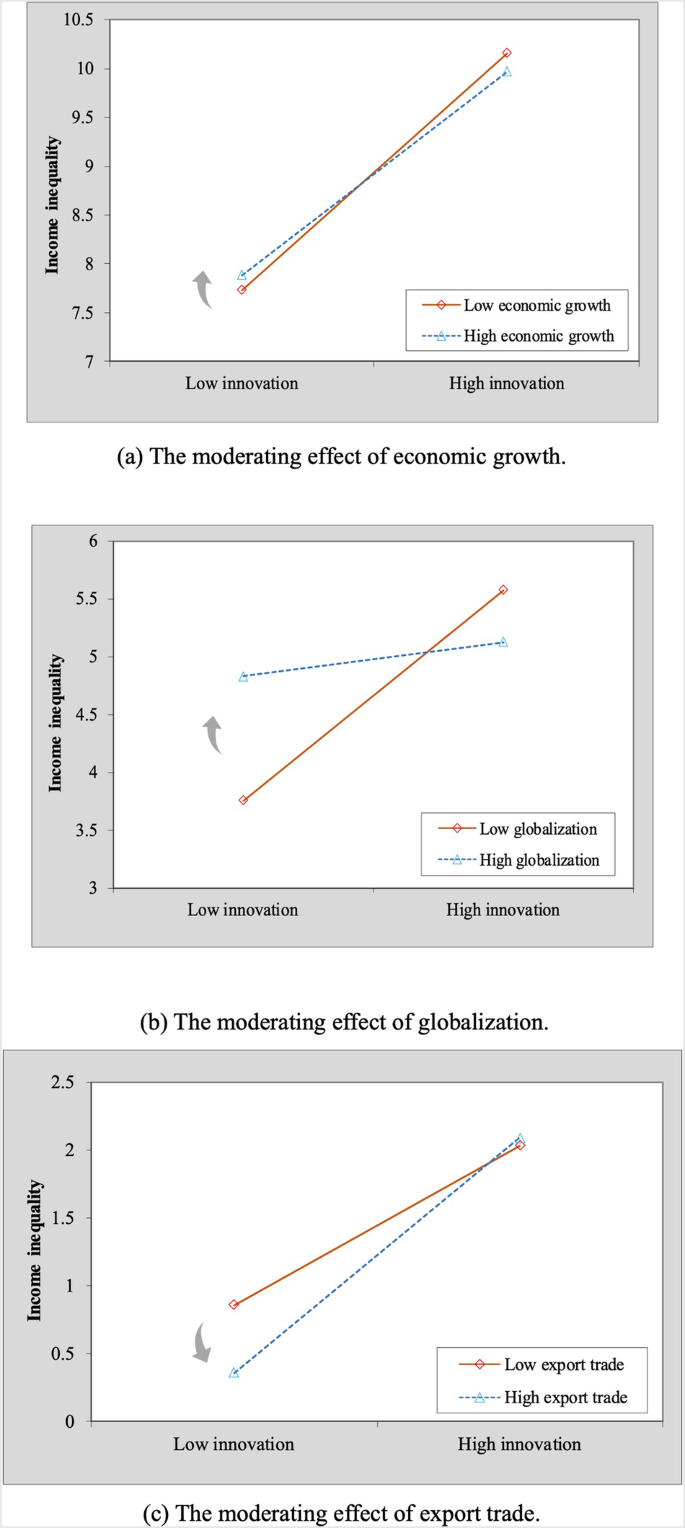

To further verify the moderating effect, this paper draws diagrams of the moderating effect in developed and developing countries (Figs. 1 and 2 ) to more intuitively reflect the moderating effect on the relationship between technological innovation and INE. In Fig. 1a , the slope becomes larger during the transition from low to high economic growth, indicating that the effect of technological innovation on INE is stronger when economic growth is at a higher level in developed countries. In other words, economic growth positively moderates the positive effect of technological innovation on INE, and H2a is further tested. Consistent with the previous discussions, Fig. 1b and Fig. 1c demonstrate how globalisation and export trade buffer the positive association between technological innovation and income disparity, respectively. In developing countries, the positive moderating effect of export trade and the negative moderating effect of economic growth and globalisation are all evident in Fig. 2 . In summary, H2a, H2b and H2c cannot be rejected.

The moderating effect of moderators on the relationship between technological innovation and income inequality in developed countries.

The moderating effect of moderators on the relationship between technological innovation and income equality in developing countries.

Robustness test

We apply the AMG method to shed light on the robustness of the regression results obtained by the CCEMG estimator, and the robustness test results for Model I are reported in Table 5 . The robustness test results match those of the CCEMG estimator, indicating that technological innovation significantly promotes INE. Similarly, Tables 6 and 7 report the robustness test results for Model II–Model VI. Although the magnitudes of the regression coefficients fluctuate slightly, the signs of the coefficients are consistent with the regression results. In developed countries, globalisation and export trade buffer the inequality-enhancing effects of technological innovation, but economic development boosts it. In developing countries, economic development and globalisation negatively moderate the positive links between technological innovation and inequality, while export trade exacerbates it. In summary, the empirical findings align with those of CCEMG, supporting the validity and robustness of our conclusions.

Heterogeneity analysis at the chronological level

The baseline regression assumes that technological innovation has the same impact on income equality over time and ignores the enormous historical variance in variables such as global trade policy, economic development and financial markets. Therefore, a heterogeneity analysis is conducted to further explore the nexus between technological innovation and INE under various chronologies. The samples of developing and developed countries are split into two 13-year sub-periods (1995–2007 and 2008–2020) to separately probe the heterogeneity of the impact of chronology on the regression results of Model I–Model IV. Table 8 presents the regression results of the effect on INE in developed countries by sub-period. For Model I in Table 8 , technological innovation significantly positively affects INE in developed countries in sub-period I and sub-period II. However, the equality-diminishing effect is much stronger in the latter, i.e., a 1% increase in technological innovation leads to a 0.286% increase in INE. In line with the baseline model, technological innovation in developed countries undeniably widens the gap between the poor and the rich to a greater extent over time. Economic globalisation was the most significant trend influencing the growth of the global economy at the turn of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st century. National economies are intertwined, engaging in varied degrees of collaboration and regulation and moving towards integration due to the technological revolution and the internationalisation of production. This inevitably drove a rapid technological revolution. However, individuals have different abilities to adapt to the knowledge generated by innovative activities, increasing the skill premium, which inevitably creating a gap between high-skilled and low-skilled individuals. Eventually, as sub-period I progresses to sub-period II, it fosters the inequality-exacerbating effect in developed countries.

For Model II in Table 8 , the interaction between economic growth and technological innovation attenuates INE in sub-period I. However, the opposite is true in sub-period II. In sub-period I, economic expansion encourages more innovation, which leads to more creative destruction and a consequent decline in wealth and rent disparity. According to Antonelli and Gehringer ( 2017 ), countries with more income asymmetry experience the influence of technological change more noticeably. In the latter stages, the increased demand for highly skilled workers, likely due to high economic growth, results in intensifying skill-biased technology development and job polarisation. Ultimately, this leads to increased INE in sub-period II. For Model III in Table 8 , the results of the heterogeneity analysis are consistent with those in Table 3 , proving that globalisation acts as a buffer moderator in the relationship between technological innovation and inequality. Notably, in Model IV, the interaction between technological innovation and export trade is significant only in sub-period II, showing that the moderating effect only occurs at the later stage. In sub-period II of the trade take-off, developed economies have relatively abundant high-skill factors. Thus, the opening up of trade exacerbates the wage premiums of high-skilled workers. Conversely, low-skilled workers may suffer unemployment or a higher employment threshold. This phenomenon generated by the development of trade liberalisation widens the income gap between the two classes.

Table 9 shows the regression results of the effect on INE in developing countries by sub-period. For Model I in Table 9 , it is worth remembering that technological innovation’s effects on inequality have contradictory consequences over time; specifically, technological innovation increases INE in sub-period I but has the reverse effect in sub-period II. In the early stages of technological innovation development, technology leads to rapid profit growth, exacerbating INE between sectors. Specifically, due to sectoral heterogeneity, a few sectors benefit from technological innovation, leading to them commanding a greater share of income, further increasing the income gap across sectors. However, in the mature stage of technology development, the benefits enjoyed by incumbents are reduced due to the creative destruction of new entrants, and revenue expansion slows down in technology-profitable industries. Coupled with the adoption of technology-oriented income redistribution policies, income disparities within sectors decline (Hatipoglu, 2012 ). Economic growth always serves as the accelerator of the nexus between technological innovation and income disparity, according to Model II in Table 9 . In sub-period I, economic growth exacerbates the inequality-increasing effect, but in sub-period II, it promotes the inequality-decreasing effect. In summary, the results generated by the baseline model can ultimately determine which way the accelerator-driven wheels rotate. According to Model III in Table 9 , globalisation plays a similar role to that of economic development in the links between technological innovation and inequality, acting as a gas pedal to exacerbate INE in sub-period II. This finding aligns with Law et al. ( 2020 ), who contended that globalisation is a gas pedal for technological innovation’s positive effect on inequality. For Model IV in Table 9 , the state of the situation in developing countries is comparable to that in developed countries.

Causality test results

Exploring the direction of the causal relationship between INE, globalisation, economic growth and export trade can assist policymakers in establishing a basket of appropriate trade and economic policies to support the realisation of equitable income. The causality test results (Dumitrescu and Hurlin, 2012 ) are shown in Table 10 , indicating a bidirectional causal relationship between economic growth, globalisation, export trade and INE in developed countries. The results for developing countries remain consistent with those for developed countries, except for the absence of a causal relationship between globalisation and inequality. Notably, technological innovation and INE affect one another, which is the so-called feedback effect. This result aligns with Aghion et al. ( 2019 ), who verified the positive feedback mechanism in technological innovation and INE. At a particular innovation rate and incentive, innovation scaling encourages innovation profits, expands the proportion of entrepreneurial income and increases inequality. As a result, newcomers and established businesses implement more innovative activities, increasing inequality by increasing the proportion of entrepreneurial income. Similarly, Tang et al. ( 2022 ) proved that technological innovation and INE Granger cause each other in middle- to low-income countries, while there is unidirectional causality in other groups. According to Hatipoglu ( 2012 ), a decrease in income disparity results in more customers purchasing goods, which affects product revenue and output. Thus, managers’ and shareholders’ decision-making regarding R&D investment is affected. The contract opinion is proposed by Rodríguez-Pose and Tselios ( 2010 ), who contended the price effect, stating that since the richest buyers can afford to purchase new products, INE promotes technological innovation to some extent. The latent endogeneity of the links between technological innovation and INE is revealed by Benos and Tsiachtsiras ( 2019 ), who examined the reverse causality of inequality affecting technological innovation, namely, creative initiatives contribute to alleviating income disparity by pairing patents with inventors. In addition, a bidirectional causal relationship exists between INE and economic growth, consistent with the findings of Yang and Greaney ( 2017 ), who asserted that inequality growth leads to considerable capital accumulation, which stimulates economic growth. An analysis of China from 1980 to 2013 concluded that economic growth led to unfair income distribution (Koh et al. 2020 ). A “feedback effect” also exists between globalisation and INE. This finding is supported by Abakumova and Primierova ( 2018 ), who confirmed the Granger causal relationship between globalisation and INE. Similarly, the causality between export trade and INE is also bidirectional. Since most factors affect income disparity, point-to-point-focused policies should be implemented rather than the one-size-fits-all approach.

Discussions

Analysis of the direct effect of technological innovation on ine.

According to the regression results, technological innovation exacerbates INE in developing and developed countries, with the inequality-exacerbation effect being more prominent in the latter. Subsequently, we discuss the inequality-exacerbating impact at three levels: individual, sectoral and national. Figure A6 represents the causal relationships between variables in developed and developing countries.

First, individual variations in acquiring and mastering new technologies are the critical genesis of the inequality-exacerbating effect. This disparity can result from the gap in access to education resources or individual ability. Digital technology is intended to be a powerful tool for reducing socioeconomic disparities, but there are significant gaps in access and adoption among different income groups. This digital divide means that while digital technology has injected a powerful impetus into social development, its dividends have not reached all groups evenly. Conversely, knowledge-adaptive workers are better equipped to expand their skills in a rapidly volatile technology environment (Benos and Tsiachtsiras, 2019 ). The demand for high-skilled workers rises in response to innovative activities, raising the skills premium for those with secondary and tertiary education, while low-skilled people suffer from unemployment and higher employment thresholds. In other words, low-skilled workers suffer from the dark side of technological innovation, while high-skilled workers, who take full advantage of learning opportunities, benefit from the light side. As a result, the distribution of high-skilled and low-skilled workers in the labour market is a worthwhile topic in discussions on INE. The endowment of high-skilled labour in developed countries contributes to a curse of worsening inequality (Anderson, 2008 ). Because high-skilled workers are relatively abundant in developed countries but scarce in international markets, these high-skilled workers typically receive higher salaries and greater benefits, further widening the income gap within labour. This discussion more adequately explains the finding in Table 3 that developed countries are more deeply ensnared in the technological innovation-induced inequality trap than developing countries are.

Second, the impact of technological innovation on inequality is heterogeneous across sectors. The financial sector wage premium contributes significantly to global high-income growth and widening INE across sectors. The pattern of profit sharing is overwhelmingly responsible for this phenomenon, while wage premiums due to better education and talent account for a small portion. Therefore, one of the crucial entry points for establishing policies is to focus on patterns in salary allocation across different sectors. Economic growth in the service and manufacturing industries increases inequality, while the opposite is true for agriculture (González Gordón and Resosudarmo, 2019 ). The industrial structure in developed countries is relatively complex and dominated by high-tech manufacturing and services industries, but developing countries are oriented towards agriculture and light industry. This further explains why technological innovation has less of an inequality-widening effect in developing nations. Growing poverty and polarisation often occur during the transition process of structural change in developing economies, and we emphasise the substantial influence of sectoral differentiation.

Third, the production shift to developing countries leads to significant differences in international wages. As the growth of the knowledge economy and high-tech industries drives the demand for high-skilled labour, some developed countries need more R&D researchers, which increases their market value and relative wages. Traditional manufacturing jobs are relocated to developing countries. Thus, skilled employees in developed countries must be more adaptable and proficient to achieve better professional development and salaries in a competitive job market (Iwaisako, 2009 ). Additionally, technological innovation in developed countries facilitates the utilisation of abundant technological resources, allowing for the creation of technology-intensive products with high quality and added value. However, the scarcity of such products in developing countries results in higher profits for developed countries, driving up the price of related factors and widening the income gap between different sectors in developed countries (Huang et al. 2022 ). Technological innovation increases INE, and developed countries are more deeply trapped in a downward spiral.

Analysis of the moderating effects of economic growth, globalisation and export trade

Moderating effects of economic growth.

Considering the differences between developing and developed countries, we analyse the different moderating effects of economic growth. According to Model II in Table 3 , economic growth promotes the inequality-exacerbating impact of technological innovation in developed countries. The benefits of economic growth and technological advancement are frequently concentrated in the hands of a select few, implying a higher concentration of capital and wealth in developed countries. Therefore, technology-oriented policies are required to enable more people profit from technological innovation. Additionally, higher levels of economic development tend to bring population ageing in developed countries, leading to an ageing workforce. Compared to younger people, older workers tends to remain relatively fixed in certain stable occupations and lack dynamism to enter into cutting-edge industries. This may result in a scarcity of skilled talent, generating higher wage premiums and driving a wedge between the rich and poor (Iwaisako, 2009 ).

Moreover, in the face of economic growth and globalisation, developed countries regard technological barriers as a critical strategy for sustaining their dominant position. Enterprises in developed countries tend to have stronger intellectual property protections; thus, better patent protection systems and more robust legal measures are implemented to reinforce the limitations of technical barriers. However, technological barriers privilege some companies, leading to oligopolistic markets. A competitive landscape can also affect economic inefficiency (Antonelli and Gehringer, 2017 ). Technological barriers also raise the market threshold for new entrants. Thus, incumbents are rarely subject to creative destruction, and INE from technological innovation is no longer reduced.

According to Model II in Table 4 , economic growth negatively moderates the positive links between technological innovation and INE in developing countries. First, in many developing countries, more people need to be employed due to the dominance of agriculture and a homogeneous industrial structure. High economic growth drives industrialisation and modernisation, providing employment opportunities and sources of income for numerous people and ultimately reducing INE. Additionally, economic development can promote social improvement and public services by integrating big data and artificial intelligence. In developing countries, public service systems such as education, health care and transportation could be more robust. Technological innovation can improve the quality and efficiency of public services and promote social justice by leveraging digitalisation and the Internet of Things. Finally, the interaction between economic development and technological innovation has a spillover effect (Gu et al. 2021 ). Promoting and applying technological innovation can lead to the development of related industries, thus increasing employment opportunities and income sources and generating spillover effects on society.

Moderating effects of globalisation

According to Model III in Table 3 and Table 4 , globalisation negatively moderates the inequality-exacerbating effect of technological innovation in developing and developed countries. Social globalisation can facilitate the cross-border flow of technological resources and wealth, reducing the gap between countries and regions. For example, developing countries quickly acquire advanced technologies and production methods to improve productivity and competitiveness through trade and investment matching with developed countries. Additionally, global technology exchange and sharing make it easier for more countries and regions to acquire the latest breakthroughs and cutting-edge knowledge, which assists in narrowing the technology gap. Moreover, because globalisation expands the sharing of knowledge and skill resources, more people can acquire high-skill levels through education and training. As a result, the wage gap between high-skilled and low-skilled labour is narrowed due to a shrinking of the skills and education gap. Lastly, as globalisation facilitates cross-border mobility and migration, many highly skilled and low-skilled workers can seize better employment opportunities and needed markets in various countries (Asteriou et al. 2014 ; Lang and Tavares, 2023 ). This mobility may reduce INE and create more equitable opportunities for high- and low-skilled workers.

Moderating effects of export trade

The moderating effect of export trade is related to each country’s economic development and market competitiveness. According to Model IV in Table 3 , in developed countries, export trade buffers the positive impact of technological innovation on inequality. Developed countries have mature industrial chains, technological advantages, stable markets and financial systems. Through export trade, they can sell their advantageous products to other countries, thus creating more jobs and wealth and reducing INE. With respect to globalisation and competitiveness, export trade drives industry upgrading and transformation. To improve market competitiveness, enterprises in developed countries must continuously upgrade products and services and enhance technological and managerial innovations. Industrial restructuring and labour market redistribution are frequently coupled with this industrial upgrading and transformation, which contributes to lessening inequality between different occupations, geographic areas and socioeconomic classes.

As shown in Model IV in Table 4 , export trade may accelerate the positive effects of technological innovation on inequality in developing countries. Developing countries typically need more sophisticated industrial technologies and goods with high added value. Thus, they are limited to exporting cheap raw materials and processed products. This export trade model frequently fails to promote industry upgrading and technology transfer, leaving most industries relying on low-end human resources and higher salaries concentrated on a few high-tech talents (Law et al. 2020 ). As a result, INE and social injustice occur. Since developing countries’ export trade is often dependent on external market demand, expanding export trade drives the growth of external market demand for developing countries’ products, thus stimulating enterprises to be more active in technological innovation (Castilho et al. 2012 ). Additionally, enterprises’ capital and technology levels are relatively low in developing countries. Thus, export trade can increase enterprises’ economic profit and market share, stimulating them to increase their investment in R&D and technological innovation. The interaction between export trade and technological innovation exacerbates INE.

Heterogeneity analysis by the level of economic development and chronology

This subsection further discusses the results of the heterogeneity analysis in Model I–Model IV, mainly focusing on the causes of the variations during the two distinct subperiods. Notably, technological innovation promotes inequality in the first sub-period in developing countries. Nevertheless, the situation is reversed in the second period, according to Model I in Table 3 . Technological innovation exacerbated INE in developing countries during sub-period I, mainly because the acceleration of industrialisation and urbanisation increased the demand for high-tech talent, technological innovation and capital (Castilho et al. 2012 ). However, high-tech resources are usually concentrated in the hands of a small group of elites, resulting in the intensification of INE. At the same time, due to the lack of basic infrastructure and low education levels, some labour forces need more skills and competitive advantages, making it challenging for them to share in the rewards of economic growth. In contrast, technological innovation in developing countries gradually matured and began to transform into “intelligent manufacturing” and “digital economy” during sub-period II. The growth of these fields stimulates greater talent demand and employment opportunities, as well as new income sources and redistribution strategies, reducing INE. Government investment and reform in education, health care, social security and other fields also enhance people’s productivity and social welfare, reducing INE. In conclusion, the impact of technological innovation on INE is complex. It depends not only on technological innovation but also on government policies, social systems, structural issues and many other factors.

This paper investigates the nexus between technological innovation and income equality and the interaction effects of economic growth, globalisation and export trade. For this purpose, we gather cross-country panel data for 31 developed and 28 developing countries from 1995 to 2020 for the empirical study. After confirming the slope coefficient heterogeneity and the CD of the series data, the CCEMG estimator is employed to investigate the direct effect and interaction effect among the variables. For comparison, the AMG estimator is applied to the robustness test, whose findings align with those of CCEMG, supporting the validity and robustness of our conclusions. Specifically, the results of benchmark models suggest that technological innovation exacerbates INE in developed and developing countries.

In contrast, developed countries are more deeply ensnared in the technological innovation-induced inequality trap. Moreover, the results of interaction models in developing countries indicate that economic growth positively moderates the inequality-enhancing effect of technological innovation, but globalisation and export trade buffer it. The results for developing countries prove the positive moderating effect of export trade and the negative moderating effect of economic growth and globalisation. Technological innovation’s dark side of unfair income distribution is exposed, yet exploring the buffering or exacerbating effect of moderators is instructive for policy formulation. As a result, a set of targeted policies closely integrates technological innovation, physical resources and human capital, complementing each other to jointly achieve inclusive economic, social and technological growth.

Based on the above analysis, technological innovation exacerbates INE. On the one hand, the application of new technologies impacts the labour market, resulting in an income gap between high-skilled and low-skilled workers because of differences in knowledge adaptability. On the other hand, factor-biased technological innovations cause changes in the demand for production factors, leading to a gap in price and status between various factors. Comprehensive policies should more closely intertwine physical capital, human capital and technological innovation, steering the economy, society and technology towards inclusive growth. The following are some effective recommendations: reform of the employment service system, labour protection, diversified technological innovation and inclusive digitalisation.

Skills training and vocational education are the most direct and effective ways to address the skills gap. First, government funding for vocational education and training programmes can increase skill levels among workers and employees, enabling them to adapt to changing demands and reap the benefits of new technologies while lowering the risk of unemployment. Second, it can be achieved by strengthening the workforce’s mobility between different industries and maintaining competitiveness in the job market through expanding vocational training and skills transfer capacities. Additionally, the development of labour protection legislation and the reform of the employment service system can support the provision of job information and skill training to assist unemployed people in finding promising jobs. Workers can be assured that they receive a fair share of the benefits of technological advancement through implementing policies such as collective bargaining, minimum wage regulations and income transparency. Labour aspirations for better pay and working conditions can be supported by policies that encourage the formation and strengthening of unions, cooperatives and other labour organisations.