Essay on Global Warming – Causes and Solutions

500+ words essay on global warming.

Global Warming is a term almost everyone is familiar with. But, its meaning is still not clear to most of us. So, Global warming refers to the gradual rise in the overall temperature of the atmosphere of the Earth. There are various activities taking place which have been increasing the temperature gradually. Global warming is melting our ice glaciers rapidly. This is extremely harmful to the earth as well as humans. It is quite challenging to control global warming; however, it is not unmanageable. The first step in solving any problem is identifying the cause of the problem. Therefore, we need to first understand the causes of global warming that will help us proceed further in solving it. In this essay on Global Warming, we will see the causes and solutions of Global Warming.

Causes of Global Warming

Global warming has become a grave problem which needs undivided attention. It is not happening because of a single cause but several causes. These causes are both natural as well as manmade. The natural causes include the release of greenhouses gases which are not able to escape from earth, causing the temperature to increase.

Get English Important Questions here

Further, volcanic eruptions are also responsible for global warming. That is to say, these eruptions release tons of carbon dioxide which contributes to global warming. Similarly, methane is also one big issue responsible for global warming.

So, when one of the biggest sources of absorption of carbon dioxide will only disappear, there will be nothing left to regulate the gas. Thus, it will result in global warming. Steps must be taken immediately to stop global warming and make the earth better again.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Global Warming Solutions

As stated earlier, it might be challenging but it is not entirely impossible. Global warming can be stopped when combined efforts are put in. For that, individuals and governments, both have to take steps towards achieving it. We must begin with the reduction of greenhouse gas.

Furthermore, they need to monitor the consumption of gasoline. Switch to a hybrid car and reduce the release of carbon dioxide. Moreover, citizens can choose public transport or carpool together. Subsequently, recycling must also be encouraged.

Read Global Warming Speech here

For instance, when you go shopping, carry your own cloth bag. Another step you can take is to limit the use of electricity which will prevent the release of carbon dioxide. On the government’s part, they must regulate industrial waste and ban them from emitting harmful gases in the air. Deforestation must be stopped immediately and planting of trees must be encouraged.

In short, all of us must realize the fact that our earth is not well. It needs to treatment and we can help it heal. The present generation must take up the responsibility of stopping global warming in order to prevent the suffering of future generations. Therefore, every little step, no matter how small carries a lot of weight and is quite significant in stopping global warming.

हिंदी में ग्लोबल वार्मिंग पर निबंध यहाँ पढ़ें

FAQs on Global Warming

Q.1 List the causes of Global Warming.

A.1 There are various causes of global warming both natural and manmade. The natural one includes a greenhouse gas, volcanic eruption, methane gas and more. Next up, manmade causes are deforestation, mining, cattle rearing, fossil fuel burning and more.

Q.2 How can one stop Global Warming?

A.2 Global warming can be stopped by a joint effort by the individuals and the government. Deforestation must be banned and trees should be planted more. The use of automobiles must be limited and recycling must be encouraged.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

Essay on Global Warming

- Updated on

- Apr 27, 2024

Being able to write an essay is an integral part of mastering any language. Essays form an integral part of many academic and scholastic exams like the SAT, and UPSC amongst many others. It is a crucial evaluative part of English proficiency tests as well like IELTS, TOEFL, etc. Major essays are meant to emphasize public issues of concern that can have significant consequences on the world. To understand the concept of Global Warming and its causes and effects, we must first examine the many factors that influence the planet’s temperature and what this implies for the world’s future. Here’s an unbiased look at the essay on Global Warming and other essential related topics.

Short Essay on Global Warming and Climate Change?

Since the industrial and scientific revolutions, Earth’s resources have been gradually depleted. Furthermore, the start of the world’s population’s exponential expansion is particularly hard on the environment. Simply put, as the population’s need for consumption grows, so does the use of natural resources , as well as the waste generated by that consumption.

Climate change has been one of the most significant long-term consequences of this. Climate change is more than just the rise or fall of global temperatures; it also affects rain cycles, wind patterns, cyclone frequencies, sea levels, and other factors. It has an impact on all major life groupings on the planet.

Also Read: Essay on Yoga Day

Also Read: Speech on Yoga Day

What is Global Warming?

Global warming is the unusually rapid increase in Earth’s average surface temperature over the past century, primarily due to the greenhouse gases released by people burning fossil fuels . The greenhouse gases consist of methane, nitrous oxide, ozone, carbon dioxide, water vapour, and chlorofluorocarbons. The weather prediction has been becoming more complex with every passing year, with seasons more indistinguishable, and the general temperatures hotter.

The number of hurricanes, cyclones, droughts, floods, etc., has risen steadily since the onset of the 21st century. The supervillain behind all these changes is Global Warming. The name is quite self-explanatory; it means the rise in the temperature of the Earth.

Also Read: What is a Natural Disaster?

What are the Causes of Global Warming?

According to recent studies, many scientists believe the following are the primary four causes of global warming:

- Deforestation

- Greenhouse emissions

- Carbon emissions per capita

Extreme global warming is causing natural disasters , which can be seen all around us. One of the causes of global warming is the extreme release of greenhouse gases that become trapped on the earth’s surface, causing the temperature to rise. Similarly, volcanoes contribute to global warming by spewing excessive CO2 into the atmosphere.

The increase in population is one of the major causes of Global Warming. This increase in population also leads to increased air pollution . Automobiles emit a lot of CO2, which remains in the atmosphere. This increase in population is also causing deforestation, which contributes to global warming.

The earth’s surface emits energy into the atmosphere in the form of heat, keeping the balance with the incoming energy. Global warming depletes the ozone layer, bringing about the end of the world. There is a clear indication that increased global warming will result in the extinction of all life on Earth’s surface.

Also Read: Land, Soil, Water, Natural Vegetation, and Wildlife Resources

Solutions for Global Warming

Of course, industries and multinational conglomerates emit more carbon than the average citizen. Nonetheless, activism and community effort are the only viable ways to slow the worsening effects of global warming. Furthermore, at the state or government level, world leaders must develop concrete plans and step-by-step programmes to ensure that no further harm is done to the environment in general.

Although we are almost too late to slow the rate of global warming, finding the right solution is critical. Everyone, from individuals to governments, must work together to find a solution to Global Warming. Some of the factors to consider are pollution control, population growth, and the use of natural resources.

One very important contribution you can make is to reduce your use of plastic. Plastic is the primary cause of global warming, and recycling it takes years. Another factor to consider is deforestation, which will aid in the control of global warming. More tree planting should be encouraged to green the environment. Certain rules should also govern industrialization. Building industries in green zones that affect plants and species should be prohibited.

Also Read: Essay on Pollution

Effects of Global Warming

Global warming is a real problem that many people want to disprove to gain political advantage. However, as global citizens, we must ensure that only the truth is presented in the media.

This decade has seen a significant impact from global warming. The two most common phenomena observed are glacier retreat and arctic shrinkage. Glaciers are rapidly melting. These are clear manifestations of climate change.

Another significant effect of global warming is the rise in sea level. Flooding is occurring in low-lying areas as a result of sea-level rise. Many countries have experienced extreme weather conditions. Every year, we have unusually heavy rain, extreme heat and cold, wildfires, and other natural disasters.

Similarly, as global warming continues, marine life is being severely impacted. This is causing the extinction of marine species as well as other problems. Furthermore, changes are expected in coral reefs, which will face extinction in the coming years. These effects will intensify in the coming years, effectively halting species expansion. Furthermore, humans will eventually feel the negative effects of Global Warming.

Also Read: Concept of Sustainable Development

Sample Essays on Global Warming

Here are some sample essays on Global Warming:

Essay on Global Warming Paragraph in 100 – 150 words

Global Warming is caused by the increase of carbon dioxide levels in the earth’s atmosphere and is a result of human activities that have been causing harm to our environment for the past few centuries now. Global Warming is something that can’t be ignored and steps have to be taken to tackle the situation globally. The average temperature is constantly rising by 1.5 degrees Celsius over the last few years.

The best method to prevent future damage to the earth, cutting down more forests should be banned and Afforestation should be encouraged. Start by planting trees near your homes and offices, participate in events, and teach the importance of planting trees. It is impossible to undo the damage but it is possible to stop further harm.

Also Read: Social Forestry

Essay on Global Warming in 250 Words

Over a long period, it is observed that the temperature of the earth is increasing. This affected wildlife, animals, humans, and every living organism on earth. Glaciers have been melting, and many countries have started water shortages, flooding, and erosion and all this is because of global warming.

No one can be blamed for global warming except for humans. Human activities such as gases released from power plants, transportation, and deforestation have increased gases such as carbon dioxide, CFCs, and other pollutants in the earth’s atmosphere. The main question is how can we control the current situation and build a better world for future generations. It starts with little steps by every individual.

Start using cloth bags made from sustainable materials for all shopping purposes, instead of using high-watt lights use energy-efficient bulbs, switch off the electricity, don’t waste water, abolish deforestation and encourage planting more trees. Shift the use of energy from petroleum or other fossil fuels to wind and solar energy. Instead of throwing out the old clothes donate them to someone so that it is recycled.

Donate old books, don’t waste paper. Above all, spread awareness about global warming. Every little thing a person does towards saving the earth will contribute in big or small amounts. We must learn that 1% effort is better than no effort. Pledge to take care of Mother Nature and speak up about global warming.

Also Read: Types of Water Pollution

Essay on Global Warming in 500 Words

Global warming isn’t a prediction, it is happening! A person denying it or unaware of it is in the most simple terms complicit. Do we have another planet to live on? Unfortunately, we have been bestowed with this one planet only that can sustain life yet over the years we have turned a blind eye to the plight it is in. Global warming is not an abstract concept but a global phenomenon occurring ever so slowly even at this moment. Global Warming is a phenomenon that is occurring every minute resulting in a gradual increase in the Earth’s overall climate. Brought about by greenhouse gases that trap the solar radiation in the atmosphere, global warming can change the entire map of the earth, displacing areas, flooding many countries, and destroying multiple lifeforms. Extreme weather is a direct consequence of global warming but it is not an exhaustive consequence. There are virtually limitless effects of global warming which are all harmful to life on earth. The sea level is increasing by 0.12 inches per year worldwide. This is happening because of the melting of polar ice caps because of global warming. This has increased the frequency of floods in many lowland areas and has caused damage to coral reefs. The Arctic is one of the worst-hit areas affected by global warming. Air quality has been adversely affected and the acidity of the seawater has also increased causing severe damage to marine life forms. Severe natural disasters are brought about by global warming which has had dire effects on life and property. As long as mankind produces greenhouse gases, global warming will continue to accelerate. The consequences are felt at a much smaller scale which will increase to become drastic shortly. The power to save the day lies in the hands of humans, the need is to seize the day. Energy consumption should be reduced on an individual basis. Fuel-efficient cars and other electronics should be encouraged to reduce the wastage of energy sources. This will also improve air quality and reduce the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Global warming is an evil that can only be defeated when fought together. It is better late than never. If we all take steps today, we will have a much brighter future tomorrow. Global warming is the bane of our existence and various policies have come up worldwide to fight it but that is not enough. The actual difference is made when we work at an individual level to fight it. Understanding its import now is crucial before it becomes an irrevocable mistake. Exterminating global warming is of utmost importance and each one of us is as responsible for it as the next.

Also Read: Essay on Library: 100, 200 and 250 Words

Essay on Global Warming UPSC

Always hear about global warming everywhere, but do we know what it is? The evil of the worst form, global warming is a phenomenon that can affect life more fatally. Global warming refers to the increase in the earth’s temperature as a result of various human activities. The planet is gradually getting hotter and threatening the existence of lifeforms on it. Despite being relentlessly studied and researched, global warming for the majority of the population remains an abstract concept of science. It is this concept that over the years has culminated in making global warming a stark reality and not a concept covered in books. Global warming is not caused by one sole reason that can be curbed. Multifarious factors cause global warming most of which are a part of an individual’s daily existence. Burning of fuels for cooking, in vehicles, and for other conventional uses, a large amount of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide, and methane amongst many others is produced which accelerates global warming. Rampant deforestation also results in global warming as lesser green cover results in an increased presence of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere which is a greenhouse gas. Finding a solution to global warming is of immediate importance. Global warming is a phenomenon that has to be fought unitedly. Planting more trees can be the first step that can be taken toward warding off the severe consequences of global warming. Increasing the green cover will result in regulating the carbon cycle. There should be a shift from using nonrenewable energy to renewable energy such as wind or solar energy which causes less pollution and thereby hinder the acceleration of global warming. Reducing energy needs at an individual level and not wasting energy in any form is the most important step to be taken against global warming. The warning bells are tolling to awaken us from the deep slumber of complacency we have slipped into. Humans can fight against nature and it is high time we acknowledged that. With all our scientific progress and technological inventions, fighting off the negative effects of global warming is implausible. We have to remember that we do not inherit the earth from our ancestors but borrow it from our future generations and the responsibility lies on our shoulders to bequeath them a healthy planet for life to exist.

Also Read: Essay on Disaster Management

Climate Change and Global Warming Essay

Global Warming and Climate Change are two sides of the same coin. Both are interrelated with each other and are two issues of major concern worldwide. Greenhouse gases released such as carbon dioxide, CFCs, and other pollutants in the earth’s atmosphere cause Global Warming which leads to climate change. Black holes have started to form in the ozone layer that protects the earth from harmful ultraviolet rays.

Human activities have created climate change and global warming. Industrial waste and fumes are the major contributors to global warming.

Another factor affecting is the burning of fossil fuels, deforestation and also one of the reasons for climate change. Global warming has resulted in shrinking mountain glaciers in Antarctica, Greenland, and the Arctic and causing climate change. Switching from the use of fossil fuels to energy sources like wind and solar.

When buying any electronic appliance buy the best quality with energy savings stars. Don’t waste water and encourage rainwater harvesting in your community.

Also Read: Essay on Air Pollution

Tips to Write an Essay

Writing an effective essay needs skills that few people possess and even fewer know how to implement. While writing an essay can be an assiduous task that can be unnerving at times, some key pointers can be inculcated to draft a successful essay. These involve focusing on the structure of the essay, planning it out well, and emphasizing crucial details.

Mentioned below are some pointers that can help you write better structure and more thoughtful essays that will get across to your readers:

- Prepare an outline for the essay to ensure continuity and relevance and no break in the structure of the essay

- Decide on a thesis statement that will form the basis of your essay. It will be the point of your essay and help readers understand your contention

- Follow the structure of an introduction, a detailed body followed by a conclusion so that the readers can comprehend the essay in a particular manner without any dissonance.

- Make your beginning catchy and include solutions in your conclusion to make the essay insightful and lucrative to read

- Reread before putting it out and add your flair to the essay to make it more personal and thereby unique and intriguing for readers

Also Read: I Love My India Essay: 100 and 500+ Words in English for School Students

Ans. Both natural and man-made factors contribute to global warming. The natural one also contains methane gas, volcanic eruptions, and greenhouse gases. Deforestation, mining, livestock raising, burning fossil fuels, and other man-made causes are next.

Ans. The government and the general public can work together to stop global warming. Trees must be planted more often, and deforestation must be prohibited. Auto usage needs to be curbed, and recycling needs to be promoted.

Ans. Switching to renewable energy sources , adopting sustainable farming, transportation, and energy methods, and conserving water and other natural resources.

Relevant Blogs

For more information on such interesting topics, visit our essay writing page and follow Leverage Edu.

Digvijay Singh

Having 2+ years of experience in educational content writing, withholding a Bachelor's in Physical Education and Sports Science and a strong interest in writing educational content for students enrolled in domestic and foreign study abroad programmes. I believe in offering a distinct viewpoint to the table, to help students deal with the complexities of both domestic and foreign educational systems. Through engaging storytelling and insightful analysis, I aim to inspire my readers to embark on their educational journeys, whether abroad or at home, and to make the most of every learning opportunity that comes their way.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

This was really a good essay on global warming… There has been used many unic words..and I really liked it!!!Seriously I had been looking for a essay about Global warming just like this…

Thank you for the comment!

I want to learn how to write essay writing so I joined this page.This page is very useful for everyone.

Hi, we are glad that we could help you to write essays. We have a beginner’s guide to write essays ( https://leverageedu.com/blog/essay-writing/ ) and we think this might help you.

It is not good , to have global warming in our earth .So we all have to afforestation program on all the world.

thank you so much

Very educative , helpful and it is really going to strength my English knowledge to structure my essay in future

Thank you for the comment, please follow our newsletter to get more insights on studying abroad and exams!

Global warming is the increase in 𝓽𝓱𝓮 ᴀᴠᴇʀᴀɢᴇ ᴛᴇᴍᴘᴇʀᴀᴛᴜʀᴇs ᴏғ ᴇᴀʀᴛʜ🌎 ᴀᴛᴍᴏsᴘʜᴇʀᴇ

Leaving already?

8 Universities with higher ROI than IITs and IIMs

Grab this one-time opportunity to download this ebook

Connect With Us

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

September 2024

January 2025

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Search the United Nations

- What Is Climate Change

- Myth Busters

- Renewable Energy

- Finance & Justice

- Initiatives

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Paris Agreement

- Climate Ambition Summit 2023

- Climate Conferences

- Press Material

- Communications Tips

Causes and Effects of Climate Change

Fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – are by far the largest contributor to global climate change, accounting for over 75 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions and nearly 90 per cent of all carbon dioxide emissions. As greenhouse gas emissions blanket the Earth, they trap the sun’s heat. This leads to global warming and climate change. The world is now warming faster than at any point in recorded history. Warmer temperatures over time are changing weather patterns and disrupting the usual balance of nature. This poses many risks to human beings and all other forms of life on Earth.

Empowering women and restoring wetlands go hand in hand

Environmentalist and Women Changemaker in the World of Wetlands Cécile Ndjebet says women are crucial for sustainable environmental conservation.

wikiHow teams up with Verified to empower people with climate information

Sacred plant helps forge a climate-friendly future in Paraguay

Facts and figures.

- What is climate change?

- Causes and effects

- Myth busters

Cutting emissions

- Explaining net zero

- High-level expert group on net zero

- Checklists for credibility of net-zero pledges

- Greenwashing

- What you can do

Clean energy

- Renewable energy – key to a safer future

- What is renewable energy

- Five ways to speed up the energy transition

- Why invest in renewable energy

- Clean energy stories

- A just transition

Adapting to climate change

- Climate adaptation

- Early warnings for all

- Youth voices

Financing climate action

- Finance and justice

- Loss and damage

- $100 billion commitment

- Why finance climate action

- Biodiversity

- Human Security

International cooperation

- What are Nationally Determined Contributions

- Acceleration Agenda

- Climate Ambition Summit

- Climate conferences (COPs)

- Youth Advisory Group

- Action initiatives

- Secretary-General’s speeches

- Press material

- Fact sheets

- Communications tips

- Student Opportunities

About Hoover

Located on the campus of Stanford University and in Washington, DC, the Hoover Institution is the nation’s preeminent research center dedicated to generating policy ideas that promote economic prosperity, national security, and democratic governance.

- The Hoover Story

- Hoover Timeline & History

- Mission Statement

- Vision of the Institution Today

- Key Focus Areas

- About our Fellows

- Research Programs

- Annual Reports

- Hoover in DC

- Fellowship Opportunities

- Visit Hoover

- David and Joan Traitel Building & Rental Information

- Newsletter Subscriptions

- Connect With Us

Hoover scholars form the Institution’s core and create breakthrough ideas aligned with our mission and ideals. What sets Hoover apart from all other policy organizations is its status as a center of scholarly excellence, its locus as a forum of scholarly discussion of public policy, and its ability to bring the conclusions of this scholarship to a public audience.

- Peter Berkowitz

- Ross Levine

- Michael McFaul

- Timothy Garton Ash

- China's Global Sharp Power Project

- Economic Policy Group

- History Working Group

- Hoover Education Success Initiative

- National Security Task Force

- National Security, Technology & Law Working Group

- Middle East and the Islamic World Working Group

- Military History/Contemporary Conflict Working Group

- Renewing Indigenous Economies Project

- State & Local Governance

- Strengthening US-India Relations

- Technology, Economics, and Governance Working Group

- Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific Region

Books by Hoover Fellows

Economics Working Papers

Hoover Education Success Initiative | The Papers

- Hoover Fellows Program

- National Fellows Program

- Student Fellowship Program

- Veteran Fellowship Program

- Congressional Fellowship Program

- Media Fellowship Program

- Silas Palmer Fellowship

- Economic Fellowship Program

Throughout our over one-hundred-year history, our work has directly led to policies that have produced greater freedom, democracy, and opportunity in the United States and the world.

- Determining America’s Role in the World

- Answering Challenges to Advanced Economies

- Empowering State and Local Governance

- Revitalizing History

- Confronting and Competing with China

- Revitalizing American Institutions

- Reforming K-12 Education

- Understanding Public Opinion

- Understanding the Effects of Technology on Economics and Governance

- Energy & Environment

- Health Care

- Immigration

- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- Law & Policy

- Politics & Public Opinion

- Science & Technology

- Security & Defense

- State & Local

- Books by Fellows

- Published Works by Fellows

- Working Papers

- Congressional Testimony

- Hoover Press

- PERIODICALS

- The Caravan

- China's Global Sharp Power

- Economic Policy

- History Lab

- Hoover Education

- Global Policy & Strategy

- Middle East and the Islamic World

- Military History & Contemporary Conflict

- Renewing Indigenous Economies

- State and Local Governance

- Technology, Economics, and Governance

Hoover scholars offer analysis of current policy challenges and provide solutions on how America can advance freedom, peace, and prosperity.

- China Global Sharp Power Weekly Alert

- Email newsletters

- Hoover Daily Report

- Subscription to Email Alerts

- Periodicals

- California on Your Mind

- Defining Ideas

- Hoover Digest

- Video Series

- Uncommon Knowledge

- Battlegrounds

- GoodFellows

- Hoover Events

- Capital Conversations

- Hoover Book Club

- AUDIO PODCASTS

- Matters of Policy & Politics

- Economics, Applied

- Free Speech Unmuted

- Secrets of Statecraft

- Capitalism and Freedom in the 21st Century

- Libertarian

- Library & Archives

Support Hoover

Learn more about joining the community of supporters and scholars working together to advance Hoover’s mission and values.

What is MyHoover?

MyHoover delivers a personalized experience at Hoover.org . In a few easy steps, create an account and receive the most recent analysis from Hoover fellows tailored to your specific policy interests.

Watch this video for an overview of MyHoover.

Log In to MyHoover

Forgot Password

Don't have an account? Sign up

Have questions? Contact us

- Support the Mission of the Hoover Institution

- Subscribe to the Hoover Daily Report

- Follow Hoover on Social Media

Make a Gift

Your gift helps advance ideas that promote a free society.

- About Hoover Institution

- Meet Our Fellows

- Focus Areas

- Research Teams

- Library & Archives

Library & archives

Events, news & press.

Global Warming: Causes And Consequences

The familiar photo of the Earth spinning in the blackness of space that was taken 50 years ago by William Anders, an astronaut on the Apollo 8 lunar mission, starkly illustrated our isolation on this planet. Now we face a crisis as the climate and environmental conditions that support life as we know it become ever more fragile owing to CO 2 -induced global warming. The evidence suggests there is significant risk that areas of the Earth in tropical zones may become uninhabitable and that significant food chains will collapse in this century.

Spaceship Earth

The familiar photo of the Earth spinning in the blackness of space that was taken 50 years ago by William Anders, an astronaut on the Apollo 8 lunar mission, starkly illustrated our isolation on this planet. Now we face a crisis as the climate and environmental conditions that support life as we know it become ever more fragile owing to CO 2 -induced global warming. The evidence suggests there is significant risk that areas of the Earth in tropical zones may become uninhabitable and that significant food chains will collapse in this century. We agree with those who say that the highest human priority now is to greatly reduce human societies’ reliance on CO 2 -producing oil and coal. However, even the most optimistic projections of reduced CO 2 production and resulting reductions in climatic warming suggest that future generations will face daunting problems. Fortunately, this growing disruption is occurring at a time of unprecedented breakthroughs in science and technology. Although there are many things that can be done to ameliorate individual events, the worldwide effort is uncoordinated and there is widespread resistance from vested economic and political interest groups. Here, we first survey the consequences of the rapid rise in CO 2 emissions and then consider the possibility that new genetic technologies can help mitigate some of the biological consequences of global changes in climate patterns.

Life on Earth has evolved in an interconnected ecology determined by weather patterns, movements of global tectonic plates, and the dynamic surface chemistry of oceans and land. The creatures on Earth—all the humans, animals, plants, bacteria, fungi, and viruses—are dependent on each another as well as on this enveloping ecosystem. Since the Earth is an integrated system, significant changes in any internal component or in external influences induce movement toward a new equilibrium. Throughout the history of the Earth there have been long periods of cooling leading to growth of massive continental ice sheets, interspersed with warm intervals. While the causes of these ice ages are not fully understood, the principal contributing factors have been identified. The composition of the atmosphere, particularly the concentration of carbon dioxide and methane, is important. Also changes in the Earth’s orbit around the sun, changes in the tilt in the Earth’s axis, impacts of large meteorites, and eruptions of super volcanoes. The latter two phenomena can both put massive amounts of particulate matter and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

In two instances, biological phenomena have disrupted the composition of the atmosphere with global consequences. One was the Great Oxidation Event or the Oxidation Catastrophe, around 2.45 billion years ago. This occurred after a bacterial species, an ancestor of contemporary cyanobacteria, evolved the ability to produce oxygen as a byproduct of photosynthesis. This event had extraordinary consequences for ocean chemistry and eventually for the slow accumulation of atmospheric oxygen to contemporary levels over an interval of several million years. The newly oxygenated atmosphere was toxic to virtually all the anaerobic organisms that then populated the earth. These organisms died and were replaced by creatures that could thrive in the new oxygenated atmosphere. 1 Now, the current human-induced increase in atmospheric CO 2 is the second biological disruption of atmospheric composition that is producing global warming with credible predictions of ever more dire consequences in coming decades. Consequences we are already seeing include:

Accelerating rise in global sea level owing to irreversible melting of glacial ice in the European Alps, melting of arctic ice, and of greatest concern, melting of the land ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica.

Large changes in climate patterns that have led to cataclysmic wild fires encouraged by the hottest summers on record and extreme floods stemming from new and disruptive storm patterns.

Acidification and warming of the oceans leading to decimation of coral reefs and other changes that are disrupting the marine food chain.

The global redistribution of bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens and their vectors out of the tropics and into temperate zones and the emergence of previously unknown pathogens.

As the Earth’s climate continues to warm owing to increasing levels of atmospheric CO 2 the mean sea level will rise. 2 The mean sea level has risen about 8 inches since the late 1800s, and projections suggest an accelerating rise of between 2 and 6 feet by 2100. 3 The predominant contributor to the future sea level increase will be melting of the enormous land-based ice sheets and glaciers on Antarctica and Greenland. The amount of the rise will be strongly dependent on mankind’s success in limiting future CO 2 emissions. However, even the lowest estimates portend devastating consequences: 4 loss of arable land owing to flooding and salt water intrusion (e.g., Vietnam, Bangladesh, California’s Salinas valley 5 ); major population displacements (100 million people will be displaced by a three-foot rise); many coastal areas may have to be abandoned (e.g., South Florida and Miami 6 ).

We are already experiencing changes in global weather patterns. Regions accustomed to temperate temperatures and predictable periods of rainfall are seeing prolonged drought and periods of extreme high temperature, while other regions are experiencing excess rain and snowfall along with lower ambient temperatures. In parts of Australia, drought and peak summer temperatures nearing 116 o F are causing vast wildfires. Simultaneously, U.S. states around the Great Lakes have experienced winter temperatures of -34 o C (-29.2 o F) that are significantly colder than temperatures in the Arctic. This skewing of ambient temperatures in North America is due to changes in the jet stream that have allowed polar air from the Arctic to flow into zones normally buffered against temperature extremes. Global warming contributes to these unusual weather patterns through its influence on the polar vortex, a wide expanse of swirling cold air near the pole. 7 Over a surprisingly short time, the average temperature rise at the north polar region has been higher than in some more southerly areas. While average temperatures across the globe have now increased to 1.2 o C above preindustrial revolution levels, the poles have seen an average increase of 3 o C. During March 2018, temperatures in Siberia were 15 o C (59 o F) above historical averages, and Greenland experienced a period of 61 hours above freezing (three times longer than any previous year), while temperatures were unusually low in Europe. These disruptions in global weather patterns have caused long-term drought conditions in some regions and unprecedented floods in others, leading to loss of arable land and precipitous reductions in agricultural production. Those who deny climate change often point to periods of extreme cold in unexpected regions as evidence supporting their views, without understanding that the large-scale changes in weather patterns are a central consequence of global warming. When the oceans warm, global weather patterns are disrupted in many areas in unexpected ways.

It is important to recognize that these global events are interconnected. For example, consider the consequences of sustained rainfall on degraded farmland: Increased rainfall leads to soil erosion, that in turn results in the release of phosphorous from fertilized soil into rivers and the oceans. That release, in turn can stimulate algal blooms and red tides, further reducing the ocean oxygen levels that are already lowered by warming waters. These phenomena add to the impacts of warming and acidification on food chains in the ocean.

What will be the impact of global warming on our land-based food supply and our ability to maintain the animals and plants we depend on? Warming is already slowing yield gains in most wheat-growing locations, and global wheat production is expected to fall by 6% for each 1°C of further temperature increase while becoming more variable. 8 Global production of corn is similarly at risk. 9 Global warming will alter world food production patterns, with crop productivity reduced in low latitudes and tropical regions but increased somewhat in high latitude regions. This will lead to trade changes with expanded sales of food products from the mid-to-high latitudes to lower latitude regions. 10

Extinction of species owing to expanding human activities around the globe has been accelerating over the last two centuries. Now the onset of changes in the climate is accelerating the rate of extinctions. Disruptions of habitats, loss of food sources, and the spread of infectious diseases are happening at a rate that cannot be accommodated by evolutionary adaptation. The number of species that have gone extinct in the last century alone would have taken between 800 and 1000 years to disappear in previous mass extinctions. 11 During one of these extinctions, the Permian-Triassic extinction 250 million years ago, 12,13 the earth lost 96% of all marine species, 100% of the coral reefs, and 70% of terrestrial vertebrates. In that event, the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere led to ocean warming and to ocean acidification that together played a key role in the global loss of life. Recovery from that extinction event took more than 10 million years.

Currently, we are experiencing a 6 th mass extinction, 11 and we are approaching up to 100x higher rates of extinction than the background rate. There are two critical differences now. First, the current rate of change to the earth’s ecosystem is occurring in a few decades rather than over thousands of years as in the previous five extinction periods. Second, the events underlying the current cataclysm are man-made. Metaphorically, we are riding a runaway climate train with no one at the controls.

Effects on the Oceans

In the past there have been few established populations of invasive species identified in the high northern latitudes, that is, the northern coasts of Canada or Russia. With the continuing loss of Arctic sea ice, this situation will change. There has been rapid growth of shipping traffic along the northern coast of Russia in recent years, a large cruise ship went through the Northwest Passage in 2016, and now multiple arctic cruises are advertised each year. We can expect continuing expansion in arctic shipping activities, mineral/energy exploration, fishing, and tourism in future years. These new northern transport routes offer shorter and less expensive connections between northern hemisphere ports, so the shipping traffic will inevitably grow as more ice melts and warmer weather seasons get longer. Introduction of invasive species into these Arctic regions will follow rapidly. This will bring new challenges to the native inhabitants—humans, wildlife, and plants—of these northern ocean and terrestrial habitats. There will be greater competition for food sources and introduction of new infectious diseases. This sequence of events has occurred innumerable times before when alien populations expanded into new regions. 14

Currently, the oceans absorb 93% of the heat trapped by greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, thus slowing warming of land masses. But the resulting rapid warming of the oceans directly impacts marine life and related food chains. Consider, for example, the coral reefs along over 93,000 miles of coastline rimming the oceans—one of the largest ecosystems on the planet.

A thriving coral reef is comprised of groups of millions of identical tiny polyps a few millimeters wide and a few centimeters long, each with a calcite skeleton. Millions of these tiny stony skeletons accumulate over generations to form the large hard coral reefs found along tropical shorelines. Many of the coral species obtain most of their nutrients from photosynthetic algae plants called zooxanthellae . When the sea around them warms excessively, the polyps expel the zooxanthellae and the coral becomes completely white—a condition called coral bleaching. Corals can survive bleaching events and restore the zooxanthellae , if conditions normalize quickly enough. But the bleaching events are highly stressful, and the corals will die if occurrence of bleaching events persists. When this happens, only the dead coral skeletons—which can be immense—are left.

The Great Barrier Reef, 500 feet thick at some points, extends discontinuously for over 1500 miles off the coast of eastern Australia. By 2018, half of the Great Barrier Reef had died from heat stress. Similar damage is occurring in the Caribbean and the rest of the world’s tropical shorelines. 15,16

Loss of the ocean reef ecosystems could substantially compromise the Earths ability to sustain the health and well-being of its inhabitants. Fish populations in the coral reefs are the source of food for hundreds of millions of people. Loss of the reefs disrupts the marine food chain which causes loss of local food supplies, stressed populations, and conflicts over fishing rights.

There is now a global sense of urgency to develop methods to restore and maintain the health of the reefs considering their increasing destruction. Corals can evolve to survive in changed conditions—warmer, more acidic, etc. However, the rate of natural adaptation is too slow relative to the current rate of changes in their ocean environment, so there is widespread devastation of established reefs. This has led to efforts to accelerate the rate of adaptation. In some stressed reefs, small coral colonies are found that have successfully adapted to the local changes in temperature and increased acidity. Reef preservationists have shown that corals harvested from these colonies can be nurtured in coral “farms” and then used to seed new growth in damaged areas. Scientists are also experimenting with selective breeding to develop coral strains better adapted to changed conditions. 17–19

In Indonesia another attempt at coral reef remediation involves attaching optimized coral polyps to metal rods planted within the compromised reefs. The application of a mild electric shock causes minerals in the water to precipitate and adhere to the metal structures, thus stimulating calcification with the goal of creating the more native ‘cement’ of a reef’s exoskeleton, referred to as ‘Biorock.’ 20 The resulting limestone surface increases the growth of the corals under conditions that would normally lead to their death. All these schemes are highly promising, but there are daunting cost and logistical barriers to scaling restoration efforts to address the vast areas of lost reefs.

Global Warming Is Changing the Distribution of Animal and Plant Pathogens

The last century has seen radical changes in the pattern, volume, and speed of transport of people and cargo between widely separated regions on the planet. One consequence has been the increase in direct long-distance human transport of dangerous infectious diseases by person to person transmission. Surveillance of travelers at entry points, coupled with identification, treatment, and when necessary, quarantine of the infected persons and their contacts, has been the response strategy. But diseases that are carried by intermediate vectors, for example, mosquitoes or ticks, present a different and more complex challenge. Any such vector is adapted to thrive in some environmental niche—characterized by a temperature and rainfall range, urban or rural, indoor or outdoor, etc. When a region’s climate warms, it may become hospitable to new vectors, which will then inevitably arrive either by expansion from adjacent territories or as accidental hitchhikers in freight shipments or transport vehicles.

For example, in a remarkably short time, human viruses like Zika, Dengue, Chikungunya, Yellow Fever, and West Nile have spread into regions of the Caribbean, Latin America, and the United States that until recently had ambient temperatures below that required to support their transmission. In addition, fungal infections of food plants, like the blights infecting Cavendish bananas and cocoa trees, have become a global problem. The rapid spread of global disease caused by changes in atmospheric temperature, ocean temperature, erratic and drenching rains, and floods in one geographic location accompanied by droughts in another location is being facilitated by migration of the vectors, such as mosquitoes, ticks, bats, and rats, that carry the pathogens. Insect vectors are exquisitely sensitive to changes in temperature, and warmer temperatures increase their breeding season and life span. Zika, Dengue, Chikungunya, and Yellow Fever viruses soon follow arrival of the common Aedes aegypti mosquito and are then transmitted among humans by the female mosquito. Other mosquito species transmit West Nile virus, the malaria parasite, and the parasitic nematode worm that causes the human disfiguring disease lymphatic filariasis (elephantiasis).

Ticks are another rapidly spreading vector. Although most tick species do not harbor pathogens harmful to humans, Lyme disease is caused by a tick-borne bacterial pathogen, Borrelia burgdorferi . Until recently, ticks were inhibited over much of North America by cold winters, but with increasing average temperatures and milder winters they are becoming established further north. Lyme disease is now endemic in Canada, so the government has recently established tick surveillance networks.

The vector-borne bacterial pathogen Candidatus Liberibacter that causes citrus greening disease is a serious agricultural threat. Liberibacter are transferred to citrus trees by an insect vector, the Asian citrus psyllid or jumping plant lice. The disease causes the decline and death of citrus trees by blocking the flow of nutrients and sugars from the leaves to the roots. Once infected, the tree is doomed. Liberibacter have recently migrated along with the citrus psyllid vector to warming temperate climate zones worldwide, including ten U.S. states. 21 The resulting Citrus Greening infections have devastated the Florida citrus industry and destroyed citrus groves in Asia, Brazil, and the Dominican Republic. In the United States, the damage has been less in states further north than Florida, probably because of their cooler temperatures, but as the climate warms, the citrus greening infections will likely continue moving northward.

Owing to the huge financial impact of citrus greening, there are multiple biology-based efforts underway to disrupt the infection pathway either by eliminating the psyllid vector, by killing the bacterial Liberibacter pathogen, or by developing an infection resistant citrus tree variety. 22 Insect warfare has also been tried by introduction of a wasp that preys specifically on the Asian citrus psyllid. This strategy works, but it only reduces, rather than eliminating, the citrus psyllid population. 23

Each biological approach tried so far has its pros and cons. Insecticides can kill the citrus psyllid, but they may also threaten beneficial insects. Antibiotics may kill the Liberibacter, but their use can also increase bacterial antibiotic resistance and thus loss of antibiotic effectiveness for treating human diseases. This story of the challenges of containing the spread of the citrus greening disease is representative of similar challenges encountered in trying to deal with a myriad of newly encroaching diseases, some carried by other insect vectors. Are there better solutions on the horizon? It may be that recent advances in genetic technology will lead to more effective approaches.

Can New Genetic Technologies Reduce Global Warming Consequences?

Along with the increasing threat of climate change to human health and agriculture, we are experiencing a revolution in genetic engineering technology. Perhaps this will lead to new methods for effective surveillance and for mitigation of the redistribution of vectors that transmit disease.

The new CRISPR Cas9 technology lets us change specific genes in an insect or animal vector, thus making it either unable to serve as a reservoir for a given pathogen (known as a population modification drive) or eliminating the ability of the vector to propagate (known as a suppression drive). A suppression drive targets the reproductive capacity of the insect vector and can lead to a population crash, potentially wiping out a species. A population modification drive does not affect the reproduction capability of the insect, but it prevents the vector from harboring the pathogen or it prevents transmitting the pathogen to the human host. With these technologies, the genetic makeup of a few individuals in a targeted vector species is changed in such a manner that once these individuals are released into the wild, the change spreads rapidly throughout the entire vector population. Gene drives only affect sexually reproducing species, and thus they cannot be used directly on bacterial and viral pathogens.

Malaria transmission has been used as a test case to explore use of a vector gene drive to contain the spread of a disease. The results have been encouraging. In 2015, 200 million people worldwide were infected with malaria and between 500,000 and 700,000 died from the disease. Seventy-two percent of these were children under 5 years of age. In 2016, the number of cases worldwide increased to 216 million. Of 3,500 mosquito species, only those that belong to a subset called Anopheles can transmit the malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum , to a human by means of a bite from a female. The Anopheles stephensi mosquito, endemic to India and South Asia, carries the malaria parasite in that region. These mosquitoes were experimentally gene edited so that they could no longer carry the malaria parasite, establishing a population modification gene drive. A key trick in a gene drive is to engineer both copies of the chromosome so that all the offspring of a mating between a normal mosquito and a genetically altered one carry the genetic profile of the desired alteration, rather than just half the offspring, which is normally the case. Under laboratory conditions, it was demonstrated that this population modification drive leads to rapid spread of the desired genetically-altered mosquito and disappearance of the normal mosquitoes. The genetically altered mosquitoes cannot harbor the malaria parasite. This suggests that release of this genetically altered mosquito into the wild would halt the spread of malaria and thus save millions of lives. Eventually the malaria parasite could naturally mutate to overcome the genetic change in its mosquito host allowing it to once again infect humans, but this might not occur for a long time.

Another example is the Anopheles gambiae mosquito, which transmits malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. In another series of gene drive experiments, gene editing was used to change genes that the female mosquito needs for egg production, thereby creating female sterility (a suppression gene drive). In this case, the goal was just to reduce the number of mosquitoes transmitting malaria, but the technique could potentially wipe out the entire population of Anopheles gambiae . The combined challenge of climate change, which is altering the geographic distribution of the vector mosquitoes, and growing resistance to drugs routinely used to treat malaria-infected patients is making gene editing of the insect vectors an increasingly attractive potential solution. However, the notion of eliminating an entire insect species troubles many people.

In another test case, gene drives are being explored as a way of controlling transmission of Lyme disease by ticks on the U.S. island of Nantucket. Owing to recent increases in the population of island ticks, over 40% of the 10,000 inhabitants of Nantucket have, or have had, Lyme disease. Both deer and the white foot mouse can transmit the Lyme disease pathogen, Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria, to ticks, and the pathogen can then be transmitted to humans by the ticks. Ticks feed on the deer or white foot mice carrying Borrelia and the infected ticks bite humans, passing on Lyme disease. A plan was proposed by Kevin Esvelt (MIT) and Sam Telford (Tufts U., Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine) to use a gene drive to reduce the population of white footed mice that are infected with Borrelia . To do this, the mice would be genetically engineered so that they are immune to infection by the Lyme disease bacterial pathogen and thus could not accumulate infectious Borrelia . In this case, there would still be the same number of mice and the same number of ticks, but the number of ticks able to transmit Borrelia would be significantly reduced. Thousands of altered mice would be released on the island. The gene drive would ensure that the genetic alteration would pass down through all following generations of mice on the island, disrupting the cycle of transmission. The plan is to first test the genetically modified mice on an uninhabited island and then, with the concurrence of the inhabitants of both Nantucket Island and Martha’s Vineyard, release the genetically altered mice. The first step will be to get the concurrence and support of the inhabitants of these islands, because the gene drive would be altering the environment shared by all inhabitants.

Recently, a new gene editing application has been developed to alter the response of plants to environmental challenges. The proposed scheme involves spraying a field of plants with millions of insect vectors carrying viruses that are programmed to edit the genome of a plant such as maize to become drought resistant, in one growing season. This technique would be significantly faster than a gene drive. Further, this method would not permanently alter the genetic makeup of future plant generations, as is the case with gene drives. The goal is to engineer drought-resistant and temperature-tolerant plants, thereby securing the food supply during times of climate instability. But there is a catch, as once released into the wild, controlling these insect vectors would be difficult, if not impossible. As a result, this work has been limited so far to the laboratory. There is also concern that the method could be adapted as a biological weapon, enabling destruction of targeted food crops over wide areas by adverse genetic manipulation of the plants’ chromosomes. In addition to controlling mosquito vectors and tick-borne Lyme disease, gene drives are also being devised to control the nematode worms that carry the parasite causing Schistosomiasis.

Gene drives have not yet been released in the wild to mitigate vector-borne transmission of disease as there are critical questions to be resolved as noted above. Although the biology is ready, there are many questions of governance, safety, and ethics to be answered. Caution is important, since once the genetically-altered vectors are released, there is no assured way of controlling them at this point.

In July 2015, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences convened a meeting to discuss “the promise and perils of gene drives.” Critical questions raised at the meeting were:

Will an entire species of vector be wiped out? Methods are being devised to slow the gene drive so that only a portion of the offspring contain the genetically engineered alterations. These “Daisy chain drives,” have been engineered to be self-limiting and eventually disappear from the population.

Have techniques been devised that could control a runaway gene drive? By creating a second gene drive that undoes the genetic alterations of the first gene drive, essentially “a molecular eraser,” it is hoped a gene drive could be reversed, but not before unintended consequences to the ecosystem become apparent.

Can the altered genetic traits be transferred to other insect species ? Unlikely, but possible. If this occurred, the potential for wiping out beneficial insect species would lead to further ecological disruptions, compounding the ravages of climate change.

Global Warming Mitigation Will Require a Coordinated International Effort

Many climate scientists and other thoughtful people have had concerns about the deteriorating global ecosystem for several decades now. The contribution of human activity to this escalating cataclysm is well documented. Predictions of dire consequences have been noted and sporadic attempts by the international community have been made to mitigate the ongoing onslaught of carbon emissions. But global warming is a problem that can only be solved by global cooperation because the world’s ecosystem is an integrated system. The causes of environmental degradation cannot be addressed by a patchwork of uncoordinated responses. We are dependent upon achieving international cooperation to mount a coordinated, science-based response.

In the United States today, political calculations relating to oil and coal interests have halted government acknowledgement of the risks of continuing future emissions of CO 2 into the atmosphere. In December 2018, at a UN Climate Change Conference in Poland, Wells Griffith, Mr. Trump’s international energy and climate adviser, said “We strongly believe that no country should have to sacrifice their economic prosperity or energy security in pursuit of environmental sustainability.” The attendees broke into jeers and mocking laughter. 24 Do not think that the United States is alone in this stance. We are aligned with other major fossil fuel producing nations, including Russia, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Australia. We are now well beyond the time of debating about validity of the predictions about what will happen if climate change is left unaddressed. Rather, we are trying to mitigate what has already happened, while, as a society, summoning the courage and the will to leave fossil fuels in the ground and switch to alternative energy sources. Renewable power resources and improvements in the efficiency of our energy use can be important components of our energy future for the rest of this century. But, practically speaking, nuclear power will probably also have to be a major component of the future energy portfolio in order to meet world energy demands while greatly reducing use of fossil fuels. 25, 26 That too is controversial. These are existential choices that call for an unprecedented level of wisdom and societal responsiveness in the world’s political systems. It does seem likely that achieving the necessary global political response will only come when there is widespread public fear and panic as the realization of the danger percolates into public consciousness. 27 It is extraordinary that the current U.S. national leadership both denies existence of the global warming problem and actively promotes more use of fossil fuels. The longer we delay reduction in global CO 2 emissions, the worse the ultimate catastrophe will be.

Authors’ Note:

We believe the world energy economy must shift rapidly from reliance on fossil fuels—coal, oil, and gas—to cleaner alternatives or our children and grandchildren will suffer dire consequences. We encourage the reader to personally assess the risks and potential solutions. To that end, we have included references for further reading that are openly accessible on the Internet.

Lucy Shapiro is a professor in the Department of Developmental Biology at Stanford University School of Medicine where she holds the Virginia and D. K. Ludwig Chair in Cancer Research and is the director of the Beckman Center for Molecular and Genetic Medicine. Harley McAdams is an emeritus professor at the Department of Developmental Biology at Stanford University School of Medicine.

View the discussion thread.

Join the Hoover Institution’s community of supporters in ideas advancing freedom.

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Global warming.

The causes, effects, and complexities of global warming are important to understand so that we can fight for the health of our planet.

Earth Science, Climatology

Tennessee Power Plant

Ash spews from a coal-fueled power plant in New Johnsonville, Tennessee, United States.

Photograph by Emory Kristof/ National Geographic

Global warming is the long-term warming of the planet’s overall temperature. Though this warming trend has been going on for a long time, its pace has significantly increased in the last hundred years due to the burning of fossil fuels . As the human population has increased, so has the volume of fossil fuels burned. Fossil fuels include coal, oil, and natural gas, and burning them causes what is known as the “greenhouse effect” in Earth’s atmosphere.

The greenhouse effect is when the sun’s rays penetrate the atmosphere, but when that heat is reflected off the surface cannot escape back into space. Gases produced by the burning of fossil fuels prevent the heat from leaving the atmosphere. These greenhouse gasses are carbon dioxide , chlorofluorocarbons, water vapor , methane , and nitrous oxide . The excess heat in the atmosphere has caused the average global temperature to rise overtime, otherwise known as global warming.

Global warming has presented another issue called climate change. Sometimes these phrases are used interchangeably, however, they are different. Climate change refers to changes in weather patterns and growing seasons around the world. It also refers to sea level rise caused by the expansion of warmer seas and melting ice sheets and glaciers . Global warming causes climate change, which poses a serious threat to life on Earth in the forms of widespread flooding and extreme weather. Scientists continue to study global warming and its impact on Earth.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

February 21, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Lisa Hupp/USFWS

Arctic Match Live Now!

For a limited time, all gifts are being matched to stop Big Oil from blocking a new once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to protect the Arctic.

Global Warming 101

Everything you wanted to know about our changing climate but were too afraid to ask.

Temperatures in Beijing rose above 104 degrees Fahrenheit on July 6, 2023.

Jia Tianyong/China News Service/VCG via Getty Images

- Share this page block

What is global warming?

What causes global warming, how is global warming linked to extreme weather, what are the other effects of global warming, where does the united states stand in terms of global-warming contributors, is the united states doing anything to prevent global warming, is global warming too big a problem for me to help tackle.

A: Since the Industrial Revolution, the global annual temperature has increased in total by a little more than 1 degree Celsius, or about 2 degrees Fahrenheit. Between 1880—the year that accurate recordkeeping began—and 1980, it rose on average by 0.07 degrees Celsius (0.13 degrees Fahrenheit) every 10 years. Since 1981, however, the rate of increase has more than doubled: For the last 40 years, we’ve seen the global annual temperature rise by 0.18 degrees Celsius, or 0.32 degrees Fahrenheit, per decade.

The result? A planet that has never been hotter . Nine of the 10 warmest years since 1880 have occurred since 2005—and the 5 warmest years on record have all occurred since 2015. Climate change deniers have argued that there has been a “pause” or a “slowdown” in rising global temperatures, but numerous studies, including a 2018 paper published in the journal Environmental Research Letters , have disproved this claim. The impacts of global warming are already harming people around the world.

Now climate scientists have concluded that we must limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2040 if we are to avoid a future in which everyday life around the world is marked by its worst, most devastating effects: the extreme droughts, wildfires, floods, tropical storms, and other disasters that we refer to collectively as climate change . These effects are felt by all people in one way or another but are experienced most acutely by the underprivileged, the economically marginalized, and people of color, for whom climate change is often a key driver of poverty, displacement, hunger, and social unrest.

A: Global warming occurs when carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) and other air pollutants collect in the atmosphere and absorb sunlight and solar radiation that have bounced off the earth’s surface. Normally this radiation would escape into space, but these pollutants, which can last for years to centuries in the atmosphere, trap the heat and cause the planet to get hotter. These heat-trapping pollutants—specifically carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, water vapor, and synthetic fluorinated gases—are known as greenhouse gases, and their impact is called the greenhouse effect.

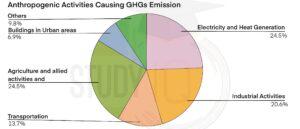

Though natural cycles and fluctuations have caused the earth’s climate to change several times over the last 800,000 years, our current era of global warming is directly attributable to human activity—specifically to our burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil, gasoline, and natural gas, which results in the greenhouse effect. In the United States, the largest source of greenhouse gases is transportation (29 percent), followed closely by electricity production (28 percent) and industrial activity (22 percent). Learn about the natural and human causes of climate change .

Curbing dangerous climate change requires very deep cuts in emissions, as well as the use of alternatives to fossil fuels worldwide. The good news is that countries around the globe have formally committed—as part of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement —to lower their emissions by setting new standards and crafting new policies to meet or even exceed those standards. The not-so-good news is that we’re not working fast enough. To avoid the worst impacts of climate change, scientists tell us that we need to reduce global carbon emissions by as much as 40 percent by 2030. For that to happen, the global community must take immediate, concrete steps: to decarbonize electricity generation by equitably transitioning from fossil fuel–based production to renewable energy sources like wind and solar; to electrify our cars and trucks; and to maximize energy efficiency in our buildings, appliances, and industries.

A: Scientists agree that the earth’s rising temperatures are fueling longer and hotter heat waves , more frequent droughts , heavier rainfall , and more powerful hurricanes .

In 2015, for example, scientists concluded that a lengthy drought in California—the state’s worst water shortage in 1,200 years —had been intensified by 15 to 20 percent by global warming. They also said the odds of similar droughts happening in the future had roughly doubled over the past century. And in 2016, the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine announced that we can now confidently attribute some extreme weather events, like heat waves, droughts, and heavy precipitation, directly to climate change.

The earth’s ocean temperatures are getting warmer, too—which means that tropical storms can pick up more energy. In other words, global warming has the ability to turn a category 3 storm into a more dangerous category 4 storm. In fact, scientists have found that the frequency of North Atlantic hurricanes has increased since the early 1980s, as has the number of storms that reach categories 4 and 5. The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season included a record-breaking 30 tropical storms, 6 major hurricanes, and 13 hurricanes altogether. With increased intensity come increased damage and death. The United States saw an unprecedented 22 weather and climate disasters that caused at least a billion dollars’ worth of damage in 2020, but, according to NOAA, 2017 was the costliest on record and among the deadliest as well: Taken together, that year's tropical storms (including Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria) caused nearly $300 billion in damage and led to more than 3,300 fatalities.

The impacts of global warming are being felt everywhere. Extreme heat waves have caused tens of thousands of deaths around the world in recent years. And in an alarming sign of events to come, Antarctica has lost nearly four trillion metric tons of ice since the 1990s. The rate of loss could speed up if we keep burning fossil fuels at our current pace, some experts say, causing sea levels to rise several meters in the next 50 to 150 years and wreaking havoc on coastal communities worldwide.

A: Each year scientists learn more about the consequences of global warming , and each year we also gain new evidence of its devastating impact on people and the planet. As the heat waves, droughts, and floods associated with climate change become more frequent and more intense, communities suffer and death tolls rise. If we’re unable to reduce our emissions, scientists believe that climate change could lead to the deaths of more than 250,000 people around the globe every year and force 100 million people into poverty by 2030.

Global warming is already taking a toll on the United States. And if we aren’t able to get a handle on our emissions, here’s just a smattering of what we can look forward to:

- Disappearing glaciers, early snowmelt, and severe droughts will cause more dramatic water shortages and continue to increase the risk of wildfires in the American West.

- Rising sea levels will lead to even more coastal flooding on the Eastern Seaboard, especially in Florida, and in other areas such as the Gulf of Mexico.

- Forests, farms, and cities will face troublesome new pests , heat waves, heavy downpours, and increased flooding . All of these can damage or destroy agriculture and fisheries.

- Disruption of habitats such as coral reefs and alpine meadows could drive many plant and animal species to extinction.

- Allergies, asthma, and infectious disease outbreaks will become more common due to increased growth of pollen-producing ragweed , higher levels of air pollution , and the spread of conditions favorable to pathogens and mosquitoes.

Though everyone is affected by climate change, not everyone is affected equally. Indigenous people, people of color, and the economically marginalized are typically hit the hardest. Inequities built into our housing , health care , and labor systems make these communities more vulnerable to the worst impacts of climate change—even though these same communities have done the least to contribute to it.

A: In recent years, China has taken the lead in global-warming pollution , producing about 26 percent of all CO2 emissions. The United States comes in second. Despite making up just 4 percent of the world’s population, our nation produces a sobering 13 percent of all global CO2 emissions—nearly as much as the European Union and India (third and fourth place) combined. And America is still number one, by far, in cumulative emissions over the past 150 years. As a top contributor to global warming, the United States has an obligation to help propel the world to a cleaner, safer, and more equitable future. Our responsibility matters to other countries, and it should matter to us, too.

A: We’ve started. But in order to avoid the worsening effects of climate change, we need to do a lot more—together with other countries—to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and transition to clean energy sources.

Under the administration of President Donald Trump (a man who falsely referred to global warming as a “hoax”), the United States withdrew from the Paris Climate Agreement, rolled back or eliminated dozens of clean air protections, and opened up federally managed lands, including culturally sacred national monuments, to fossil fuel development. Although President Biden has pledged to get the country back on track, years of inaction during and before the Trump administration—and our increased understanding of global warming’s serious impacts—mean we must accelerate our efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Despite the lack of cooperation from the Trump administration, local and state governments made great strides during this period through efforts like the American Cities Climate Challenge and ongoing collaborations like the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative . Meanwhile, industry and business leaders have been working with the public sector, creating and adopting new clean-energy technologies and increasing energy efficiency in buildings, appliances, and industrial processes.